Society

Why mother language-based science education is essential

All people are touched by science; shouldn’t that be universally understood? Shouldn’t everyone take part in this?

EdPublica looks into the importance of mother language-based science education in the context of International Mother Language Day on February 21. We believe that the global fabric of linguistic diversity is facing a growing threat with the rapid disappearance of numerous languages over time.

Science is not democratic; it is an elitist activity…an Indian theoretical physicist once said. He means that science is not that democratic, so everyone does not need to learn, only the elite should learn. Does it make sense? All people are touched by science; shouldn’t that be universally understood? Shouldn’t everyone take part in this?

It should, but one big barrier is the language itself. Further democratising science education in the mother tongue will make this difficult topic more accessible to all.

The setting was a typical English-medium school in a rural village in the South Indian state of Kerala. The teacher seemed to be taking classes for 6th or 7th graders. She was reading the book in English without missing a single line. The teacher was very excited. However, the children’s body language did not show much enthusiasm. Many students’ expressions were just filled with a sense that they had heard something. The class was about light or something. The subject of the school visit was different, but I just talked to one or two of the children about what they were learning.

One has nothing to say about the rays of light taught by the teacher. They did not like any questions about what was said in class. A boy named Thomas (name changed) said, ‘Oh, I can’t understand any class in English, bro’.

It was a reality that most subjects taught in English were beyond the comprehension of the students there. Then the question is how to pass the examinations. “It’s a matter of just memorising and writing,” replied one of the boys. It was then that I remembered about the discussions of primary education, especially science education, in indigenous languages. Many children who pass with great marks in subjects including science have no understanding of basic science concepts. Those who are not good at memory are quickly labelled as dumb and will be marginalised in schools. This is not an isolated case but a common ‘phenomenon’ in third-world and developing countries where English is not the main language.

So, the question is: If you don’t understand, how can you learn?

The situation is deplorable if we consider how little practice there is in teaching science concepts in the mother language, particularly concerning children’s daily lives. Language is one of the main reasons why children don’t have a scientific approach to anything when they grow up.

India’s former President and eminent scientist, Dr. A P J Abdul Kalam, was once interacting with students at Dharampeeth Science College, Nagpur. The incident happened in 2011 or so. He encountered a question about how science learning can be made more creative. This was his answer: For a quick grasp of science-related concepts and greater creativity, teach children science in their mother language.

The same was repeated by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in January 2018. The Prime Minister said that children should be taught science in their native languages. But how much the country is still succeeding in that is questionable. It is a relief that the new National Education Policy of India is all in that direction, but the fundamental change needs to come in the mindset of parents and teachers.

What do studies say?

UNESCO’s Global Monitoring Report (GMR) published a landmark study five years ago. It was released on February 21, International Mother Language Day. The study pointed out that providing primary education in a language other than their own can significantly affect the learning process of children.

French is the main language in many West African schools. It is an unfamiliar language to its children. “Naturally, their learning becomes difficult on many levels,” states UNESCO’s policy paper.

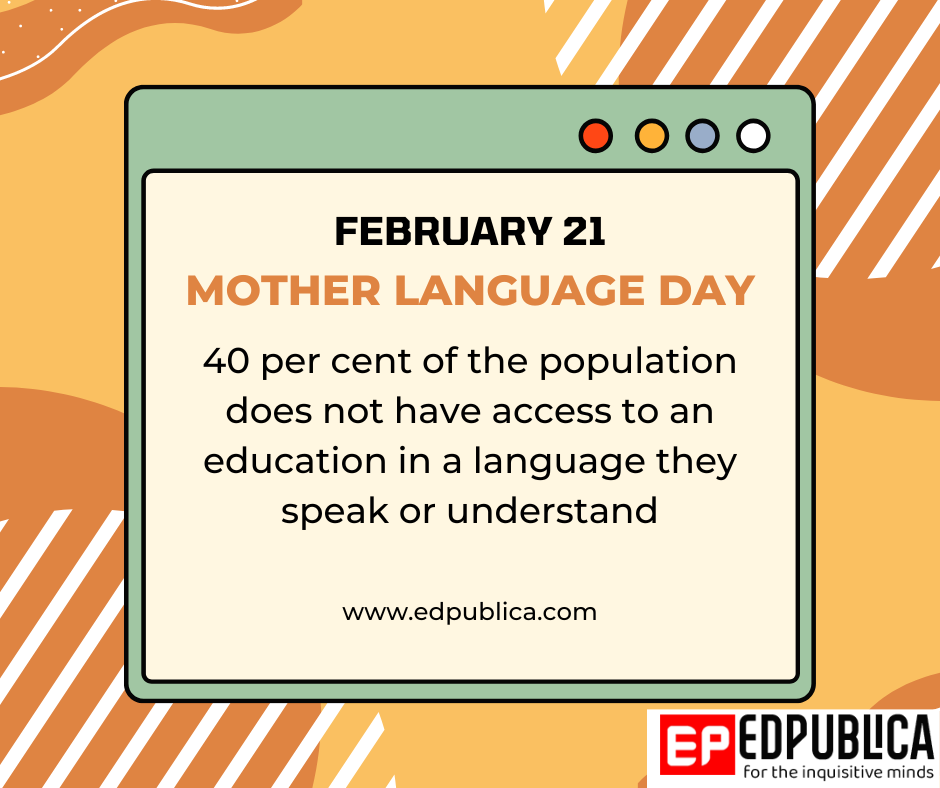

As the then UNESCO GMR Director Aaron Benavot told this writer regarding the report, “40 percent of the world’s population does not have access to education in a language they speak or understand. Studying in a non-spoken language regularly sets a student back academically. It affects children from low-income families very deeply.”

UNESCO’s report points out that if children understand the medium of learning, their learning will improve. French is the main language in many West African schools. It is an unfamiliar language to its children. “Naturally, their learning becomes difficult on many levels,” states UNESCO’s policy paper. “Language and ethnicity can combine to produce complex patterns of compounded disadvantage. In Peru, the difference in test scores between indigenous and non-indigenous children in grade 2 is sizeable and increasing.”

Why the bilingual model matters

UNESCO states that children have reached better standards in countries where bilingual programmes have been implemented in the education system. By making learning in their mother tongue possible, children can score better in all subjects. Experts such as Aaron Benavot point to Guatemalan and Ethiopian case studies as proof of this. UNESCO studies say that promoting bilingual education is the best way, even if it is a bit expensive. A bilingual education programme with an emphasis on the mother tongue can make a big difference, although it will create complications in matters including teacher recruitment.

At the same time, just because the study is in the mother language does not necessarily mean that the children will have better scientific aptitude. On the other hand, if science is taught in the mother tongue, the chances of gaining expertise in science are very high. This is mentioned in the new education policy of India. The National Education Policy calls for the use of the local language as the medium of study up to grade 5.

Moreover, such a change is essential for the democratisation of science. Celebrated Indian physicist C V Raman once said that science should be taught in the mother tongue if science is not to be confined to the activities of the elite. Science should be accessible to all. Every human life is related to science. If they want to understand it, science must come to them in a language they know.

Our transition must be to schools that teach science in the language that children speak, beyond mere theories, and relate them to their lives on a practical level. Studies have shown that children become more empowered and confident when they learn in their own language. Because the mother tongue is also related to each person’s sense of identity.

Mother Language Day 2024

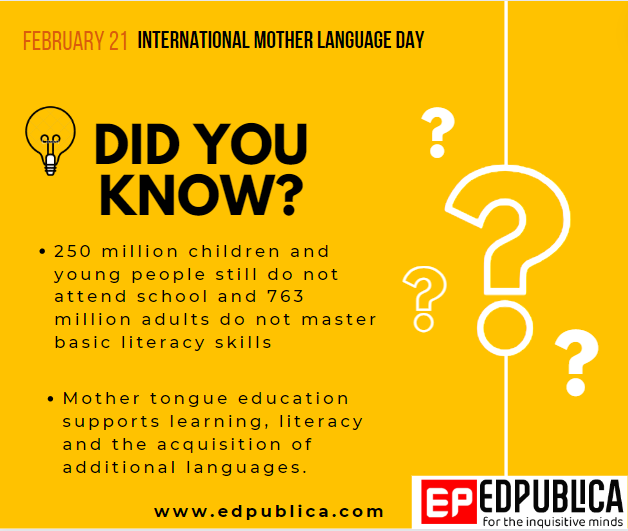

UNESCO has put forward a theme for International Mother Language Day celebration 2024 – “Multilingual education is a pillar of intergenerational learning”. Currently, 763 million adults lack basic literacy abilities, and 250 million children and young people do not attend school. UNESCO states that multilingual education is a key component of quality learning, and mother tongue education supports learning, literacy and the acquisition of additional languages.

Sustainable Energy

India’s EV Investment Story: Rs 2.23 Lakh Crore Deployed, But 82% of Capital Needs Still Unmet

India’s charger-to-EV ratio continues to lag far behind global benchmarks—a structural weakness that could slow consumer adoption.

India’s electric mobility transition has entered a decisive yet challenging phase. A new analysis from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) reveals a complex narrative: while the country’s EV sector has attracted an impressive Rs 2.23 lakh crore in investments between 2020 and 2025, this represents just 18% of what India must mobilise by 2030 to meet its ambitious clean transport goals.

Unfolding against the backdrop of India’s expanding climate commitments and rising consumer interest in EVs, the report offers a data-rich look into where capital is flowing, where it is missing, and what structural challenges remain hidden beneath headline growth.

A Five-Year Surge in Capital—But Not Enough

Between 2020 and 2025, the EV ecosystem—spanning manufacturing facilities, public subsidies, and charging networks—absorbed Rs 2,23,119 crore in funding. This includes:

- Manufacturing investments supported primarily through internal accruals

- Government subsidies, especially through FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles)

- Charging infrastructure, which remains under-capitalised

Despite this influx, India’s 2030 targets—30% of private cars, 70% of commercial vehicles, 40% of buses, and 80% of two- and three-wheelers going electric—require a total of Rs12.5 lakh crore in investments. That leaves Rs 10.26 lakh crore still unmet.

“While Rs 2.23 lakh crore is a significant capital mobilisation in just five years, it represents only about 18% of the Rs12,50,000 crore required by 2030,” says co-author Subham Shrivastava. “Mobilising the remaining INR10,26,881 crore (USD117.82 billion) by 2030 will require systemic financing reforms.”

The Anatomy of EV Capital

A closer look at the numbers reveals how India’s EV push has been financed so far.

Internal reserves dominate

Manufacturers contributed the bulk of realised investment through their own internal accruals—Rs1,59,701 crore. Debt followed at Rs36,738 crore, while equity accounted for Rs 6,455 crore. But these aggregates obscure important differences across vehicle types.

The three-wheeler segment, driven by a fragmented OEM landscape and low capital-intensity operations, leaned heavily on internal funding and limited debt. Meanwhile, two- and four-wheeler categories showed more diverse capital structures due to the presence of established players and higher investment requirements.

“From 2020–2025, electric three-wheelers attracted the largest share (~78%) of investments among vehicle segments, due to the segment’s maturity and commercial-scale operations alongside its fragmented OEM base,” explains co-author Saurabh Trivedi. “However, recent investment announcements in 2024 and 2025 reveal a pivot towards electric four-wheelers, driven by rising demand for electric cars.”

Charging Infrastructure: A Massive Funding Gap

Perhaps the most critical bottleneck in India’s EV story is the underdeveloped charging ecosystem.

From 2020 to 2025, investments in public charging constituted just 9.6% of the ₹20,600 crore estimated need for 2030. While the country expanded its public chargers from 5,151 to 39,485 over five years, utilisation rates remain low and profitability uncertain.

“Investment in EV charging faces challenges due to limited investor interest, as public EV charging remains an unproven business model, with many charging stations reporting low utilisation rates and high initial costs,” notes co-author Charith Konda.

India’s charger-to-EV ratio continues to lag far behind global benchmarks—a structural weakness that could slow consumer adoption.

The Silent Brake on India’s EV Growth

Beyond infrastructure, the economics of financing EVs present another hurdle.

Commercial EV borrowers currently face interest rates of 15–33%, levels that wipe out the total cost-of-ownership advantage EVs typically offer.

“The binding constraint is not a lack of capital in the system—it is how EV risk is priced,” Shrivastava says. “When lenders remain uncertain about battery performance, residual values, and cash-flow stability, that uncertainty gets reflected in higher interest rates.”

High financing costs disincentivise fleet operators and businesses from transitioning to EVs. As a result, manufacturing capacity cannot scale at the pace needed, creating a demand-supply mismatch.

A New Model for Mobilising Capital

To unlock the remaining ₹10.3 lakh crore needed over the next five years, IEEFA proposes a shift away from subsidy-led growth toward structural risk-sharing.

The solution: a coordinated integrated EV financing platform that consolidates:

- Partial credit guarantees

- Residual value protection for batteries

- Battery-as-a-service (BaaS) arrangements

- Co-lending structures

This platform would be anchored by development finance institutions with relevant expertise—SIDBI for MSMEs and small commercial fleets, and IIFCL for large commercial deployments.

“Manufacturers need predictable demand signals to scale capacity, but demand depends heavily on affordable credit,” Trivedi adds. “An integrated platform that shares risks appropriately across lenders, OEMs, and public institutions can reduce financing costs and unlock commercial-scale deployment.”

The idea is that as EV adoption grows and asset performance data becomes more robust, lenders will recalibrate risk premiums downward. Over time, underwriting practices could standardise, securitisation markets may emerge, and capital could recycle more efficiently.

A Self-Reinforcing Investment Loop

The report outlines a possible virtuous cycle:

- Lower financing costs stimulate EV adoption

- Higher sales volumes create better performance data

- Improved visibility reduces risk perception

- Lower risk draws in more capital

- Manufacturers scale up, benefiting from economies of scale

- Reduced costs further accelerate adoption

This dynamic, according to IEEFA, is essential for unlocking a mature and self-sustaining EV ecosystem.

A Race Between Ambition and Capital

India’s electric transport ambitions are clear and achievable—but only if the investment framework evolves as rapidly as consumer interest and technological capability.

The core message from the data is unmistakable: India is moving in the right direction, but far too slowly. Recognising this, the authors warn that the next five years will determine the trajectory of India’s EV revolution. The country must transition from policy-driven electrification to a financially self-sustaining ecosystem capable of attracting large volumes of private capital at scale.

The question is no longer about policy commitment but about the cost, structure, and flow of capital in an evolving, high-potential sector.

Climate

More Shade for the Rich: Study Exposes Global Urban Heat Inequality

New MIT research shows how wealthier neighbourhoods enjoy more tree shade, exposing global heat inequality and offering solutions for fairer urban cooling.

As extreme heat becomes a growing global concern, one of the most effective cooling tools remains remarkably simple: trees. Research has long shown that greater tree coverage in cities helps reduce surface temperatures, improve public health outcomes, and make walking more comfortable in high heat.

Yet a new international study led by researchers at MIT reveals that access to this natural relief is far from equal. Tree cover — and the shade it provides — varies drastically within cities, closely tracking neighborhood wealth.

“Shade is the easiest way to counter warm weather,” said Fabio Duarte, an MIT urban studies scholar and co-author of the study, in a media statement. “Strictly by looking at which areas are shaded, we can tell where rich people and poor people live.”

The research team analyzed sidewalk shade in nine cities across four continents: Amsterdam, Barcelona, Belem, Boston, Hong Kong, Milan, Rio de Janeiro, Stockholm, and Sydney. Despite major differences in climate, wealth, and urban form, every city showed the same trend: affluent areas consistently enjoy more tree-shaded sidewalks.

Duarte noted that this imbalance was striking even in cities globally recognized for greenery. “When we compare the most well-shaded city in our study, Stockholm, with the worst-shaded, Belem in northern Brazil, we still see marked inequality,” he said in a media statement. “Even though the most-shaded parts of Belem are less shaded than the least-shaded parts of Stockholm, shade inequality in Stockholm is greater. Rich people in Stockholm have much better shade provision as pedestrians than we see in poor areas of Stockholm.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications, in a paper titled Global patterns of pedestrian shade inequality. The research team includes scholars from Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions, and members of the MIT Senseable City Lab.

A Global Look at Uneven Shade

To quantify shade, the team used satellite imagery and detailed urban economic data to measure sidewalk coverage on both the summer solstice and the hottest day each year from 1991 to 2020. They assigned each neighbourhood a score between 0 and 1, with higher numbers indicating better shade.

Cities differed sharply in total tree cover — for instance, Stockholm’s neighbourhoods often score above 0.6, while large portions of Rio de Janeiro fall below 0.1. But the inequality within each city was consistent: the wealthiest neighbourhoods always had the greatest shade.

Even in cities known for strong environmental planning, disparities remained. “In rich cities like Amsterdam, even though it’s relatively well-shaded, the disparity is still very high,” said Lukas Beuster, a study co-author. “For us the most surprising point was not that in poor cities and more unequal societies the disparity would be notable — that was expected. What was unexpected was how the disparity still happens and is sometimes more pronounced in rich countries.”

Not all trends were uniform. Some cities, such as Barcelona and Milan, featured lower-income neighborhoods with strong shade coverage. Still, across the global sample, economic status remained a powerful indicator of access to cool, walkable streets.

Why Shade Matters — and What Cities Can Do

Sidewalks became the focal point of the study because they are crucial public spaces used daily by commuters, especially those without access to air conditioning or private vehicles. As cities worldwide face rising temperatures, researchers argue that shade must be treated as essential infrastructure.

“When it comes to those who are not protected by air conditioning, they are also using the city, walking, taking buses, and anybody who takes a bus is walking or biking to or from bus stops,” Duarte explained in a communication from MIT. “They are using sidewalks as the main infrastructure.”

Given the scale of disparity, the researchers suggest one clear strategy: target tree planting along public transit routes, where pedestrian activity is highest and where lower-income residents are most likely to walk.

“In each city, from Sydney to Rio to Amsterdam, there are people who, regardless of the weather, need to walk,” Duarte said . “Therefore, link a tree-planting scheme to a public transportation network. … If you follow transit, you will have the right shading.”

Beuster added that cities should think of urban trees as functional assets, not just aesthetic ones, emphasizing their central role in cooling and public health.

Duarte further stressed the importance of prioritizing shade where people actually move through the city. “It’s not just about planting trees,” he said in a media statement. “It’s about providing shade by planting trees. If you remove a tree that’s providing shade in a pedestrian area and you plant two other trees in a park, you are still removing part of the public function of the tree.”

“With increasing temperatures, providing shade is an essential public amenity,” he added in a media statement. “Along with providing transportation, I think providing shade in pedestrian spaces should almost be a public right.”

Climate

IEA Ministerial 2026: Global Energy Leaders Expand Ties, Push Critical Minerals Security

At the IEA Ministerial Meeting in Paris, 54 countries backed expanded membership talks with Brazil, India, Colombia and Viet Nam, while strengthening cooperation on critical minerals and clean energy security.

Global energy leaders convened in Paris this week for the International Energy Agency’s Ministerial Meeting, underscoring the agency’s expanding role in shaping international cooperation at a time of rising demand, geopolitical tensions, and accelerating energy transitions.

The two-day gathering drew senior government representatives from a record 54 countries, around 40 of them at ministerial level. Executives from 55 companies — representing a combined market capitalisation of $14 trillion — joined leaders of intergovernmental organisations in what became the largest Ministerial Meeting in the agency’s history.

At the heart of the discussions was a clear message: energy security, affordability and sustainability can no longer be pursued in isolation. They require deeper multilateral coordination, stronger data systems, and expanded institutional alliances.

Expanding the IEA Family

Member governments unanimously agreed to move forward on strengthening institutional ties with Brazil, Colombia, India and Viet Nam. In a major step, Colombia was invited to become the IEA’s 33rd Member. Brazil was invited to begin the process toward full membership following a request from its government. Ministers also welcomed recent progress in discussions with India regarding its request for full membership. Viet Nam joined as the newest Association country in the IEA Family.

The expansion significantly alters the geometry of global energy governance. With these additions, the IEA Family’s share of global energy consumption now exceeds 80%, up from less than 40% a decade ago — reflecting a profound shift in the agency’s global reach.

“This Ministerial Meeting, our largest ever, affirmed the immense value of the IEA at a moment when global energy demand is rising and the challenges facing the energy system are intensifying. In this context, our wide range of objective data and analysis is more important than ever,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol.

“In a strong step forward for global energy governance, key countries such as Brazil, Colombia, India and Viet Nam are strengthening their ties with the IEA. This puts the IEA Family’s share of global energy use at more than 80%, up from less than 40% ten years ago. With major energy issues high on the international agenda, we stand ready to support governments with the insights they need to plan for the future, helping leaders deliver on their goals of ensuring greater energy security, affordability and sustainability.”

Deputy Prime Minister Sophie Hermans of the Netherlands, who chaired the Ministerial, framed the discussions in terms of resilience amid uncertainty.

“These two days in Paris have reaffirmed how essential energy is to our daily lives – it is the invisible driving force behind everything we do. Under the umbrella of knowledge of the International Energy Agency, we have once again seen that international cooperation is key,” she said. “Our priority is clear: secure, affordable and sustainable energy – and resilient systems that can endure in an uncertain world.”

In a video address opening the meeting, French President Emmanuel Macron emphasised the IEA’s analytical leadership. “Through its in-depth analyses, and the technical expertise of its team, the IEA, under the leadership of its Executive Director Fatih Birol, plays an essential role. It enlightens us to help us guarantee our energy security and steer the energy transition.”

Beyond institutional expansion, the Ministerial marked a strong endorsement of deeper cooperation on critical minerals — increasingly viewed as the backbone of clean energy technologies.

In a special declaration, Ministers backed expanding collaboration under the IEA Critical Minerals Security Programme to address mounting risks to global supply chains. They called for strengthened data tools, collaborative exercises and clearer guidance on measures such as stockpiling, aimed at diversifying supply chains and building resilience against supply shocks.

Clean Cooking and Energy Access

Member countries also approved the integration of the Clean Cooking Alliance into the IEA, positioning the agency as the principal multilateral forum for advancing clean cooking solutions. The move seeks to accelerate access for the more than two billion people worldwide who still lack clean cooking technologies.

The integration comes ahead of the IEA’s second Summit on Clean Cooking in Africa, scheduled for July 2026 in Nairobi, where governments and industry leaders are expected to review progress since the inaugural 2024 summit and outline new financing and policy pathways.

Energy Security in the Age of Electricity

Two high-level dialogues during the Ministerial focused on safeguarding energy security in what officials termed the “Age of Electricity,” and on supporting Ukraine’s energy system amid ongoing disruptions. Ukrainian First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Energy Denys Shmyhal participated in discussions on rebuilding and securing Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

As energy demand continues to climb and transition pathways grow more complex, the IEA’s expanding membership and programme scope suggest that multilateral coordination — once largely confined to oil security — is now being repositioned as the backbone of a rapidly electrifying and mineral-intensive global energy system.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet