Space & Physics

Why does superconductivity matter?

Superconductivity was discovered by H. Kamerlingh Onnes on April 8, 1911, who was studying the resistance of solid Mercury (Hg) at cryogenic temperatures. Liquid helium was recently discovered at that time. At T = 4.2K, the resistance of Hg disappeared abruptly. This marked a transition to a new phase that was never seen before. The state is resistanceless, strongly diamagnetic, and denotes a new state of matter. K. Onnes sent two reports to KNAW (the local journal of the Netherlands), where he preferred calling the zero-resistance state ‘superconductivity’’.

There was another discovery that went unnoticed in the same experiment, which was the transition of superfluid Helium (He) at 2.2K, the so-called λ transition, below which He becomes a superfluid. However, we shall skip that discussion for now. A couple of years later, superconductivity was found in lead (Pb) at 7K. Much later, in 1941, Niobium Nitride was found to superconduct below 16 K. The burning question in those days was: what would the conductivity or resistivity of metals be at a very low temperature?

The reason behind such a question is Lord Kelvin’s suggestion that for metals, initially the resistivity decreases with falling temperature and finally climbs to infinity at zero Kelvin because electrons’ mobility becomes zero at 0 K, yielding zero conductivity and hence infinite resistivity. Kamerlingh Onnes and his assistant Jacob Clay studied the resistance of gold (Au) and platinum (Pt) down to T = 14K. There was a linear decrease in resistance until 14 K; however, lower temperatures cannot be accessed owing to the unavailability of liquid He, which eventually happened in 1908.

In fact, the experiment with Au and Pt was repeated after 1908. For Pt, the resistivity became constant after 4.2K, while Au is found to superconduct at very low temperatures. Thus, Lord Kelvin’s notion about infinite resistivity at very low temperatures was incorrect. Onnes had found that at 3 K (below the transition), the normalised resistance is about 10−7. Above 4.2 K, the resistivity starts appearing again. The transition is too sharp and falls abruptly to zero within a temperature window of 10−4 K.

All superconductors are normal metals above the transition temperature. If we ask in the periodic table where most of the superconductors are located, the answer throws some surprises. The good metals are rarely superconducting

Perfect conductors, superconductors, and magnets

All superconductors are normal metals above the transition temperature. If we ask in the periodic table where most of the superconductors are located, the answer throws some surprises. The good metals are rarely superconducting. The examples are Ag, Au, Cu, Cs, etc., which have transition temperatures of the order of ∼ 0.1K, while the bad metals, such as niobium alloys, copper oxides, and 1 MgB2, have relatively larger transition temperatures. Thus, bad metals are, in general, good superconductors. An important quantity in this regard is the mean free path of the electrons. The mean free path is of the order of a few A0 for metals (above Tc), while for good metals (or the bad superconductors), it is usually a few hundred of A0. Whereas for the bad metals (good superconductors), it is still small as the electrons are strongly coupled to phonons. The orbital overlap is large in a superconductor. In good metals, the orbital overlap is small, and often they become good magnets. In the periodic table, transition elements such as the 3D series elements, namely Al, Bi, Cd, Ga, etc., become good superconductors, while Cr, Mn, and Fe are bad superconductors and in fact form good magnets. For all of them, that is, whether they are superconductors or magnets, there is a large density of states at the Fermi level. So, a lot of electronic states are necessary for the electrons in these systems to be able to condense into a superconducting state (or even a magnetic state). The nature of the electronic wave function determines whether they develop superconducting order or magnetic order. For example, electronic wavefunctions have a large spatial extent for superconductors, while they are short-range for magnets.

Meissner effect

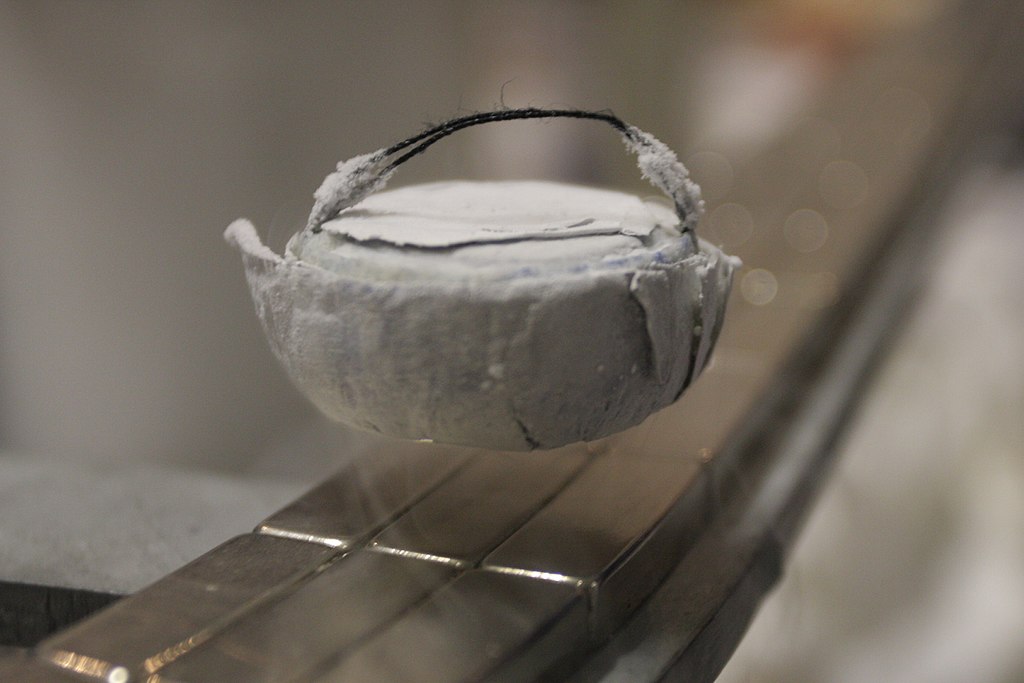

The near-complete expulsion of the magnetic field from a superconducting specimen is called the Meissner effect. In the presence of a magnetic field, the current loops at the periphery will be generated so as to block the entry of the external field inside the specimen. If a magnetic field is allowed within a superconductor, then, by Ampere’s law, there will be normal current within the sample. However, there is no normal current inside the specimen. Thus, there can’t be any magnetic field. For this reason, superconductors are known as perfect diamagnets with very large diamagnetic susceptibility. Even the best-known diamagnets (which are non-superconductors) have magnetic susceptibilities of the order of 10−5. Thus, the diamagnetic property can be considered a distinct property of superconductors compared to zero electrical resistance.

The near-complete expulsion of the magnetic field from a superconducting specimen is called the Meissner effect

A typical experiment demonstrating the Meissner effect can be thought of as follows: Take a superconducting sample (T < Tc), sprinkle iron filings around the sample, and switch on the magnetic field. The iron filings are going to line up in concentric circles around the specimen. This implies the expulsion of the flux lines outside the sample, which makes the filings line up.

Distinction between perfect conductors and superconductors

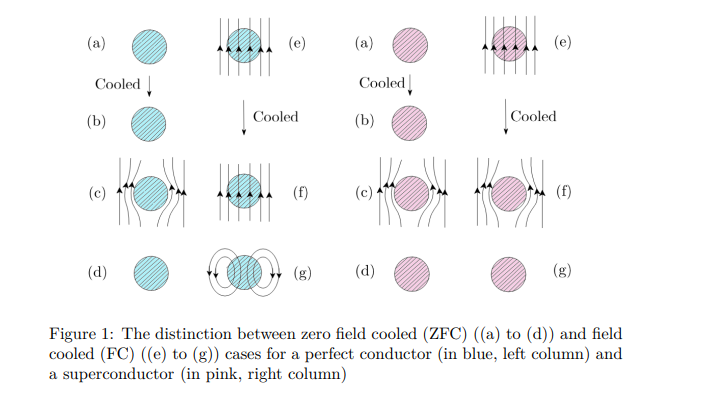

The distinction between a perfect conductor and a superconductor is brought about by magnetic field-cooled (FC) and zero-field-cooled (ZFc) cases, as shown below in Fig. 1.

In the absence of an external magnetic field, temperature is lowered for both the metal and the superconductor in their metallic states from T > Tc to T < Tc (see left panel for both in Fig. 1). Hence, a magnetic field is applied, which eventually gets expelled owing to the Meissner effect. The field has finally been withdrawn. However, if cooling is done in the presence of an external field, after the field is withdrawn, the flux lines get trapped for a perfect conductor; however, the superconductor is left with no memory of an applied field, a situation similar to what happens in the zero-field cooling case. So, superconductors have no memory, while perfect conductors have memory.

Microscopic considerations: BCS theory

The first microscopic theory of superconductivity was proposed by Berdeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer (BCS) in 1957, which earned them a Nobel Prize in 1972. The underlying assumption was that an attractive interaction between the electrons is possible, which is mediated via phonons. Thus, electrons form bound pairs under certain conditions, such as (i) two electrons in the vicinity of the filled Fermi Sea within an energy range ¯hωD (set by the phonons or lattice). (ii) The presence of phonons or the underlying lattice is confirmed by the isotope effect experiment, which confirms that the transition temperature is proportional to the mass of ions. Since the Debye frequency depends on the ionic mass, it implies that the lattice must be involved. 3 A small calculation yields that an attractive interaction is possible in a narrow range of energy. This attractive interaction causes the system to be unstable, and a long-range order develops via symmetry breaking. In a book by one of the discoverers, namely, Schrieffer, he described an analogy between a dancing floor comprising couples, dancing one with any other couple, and being completely oblivious to any other couple present in the room. The couples, while dancing, drift from one end of the room to another but do not collide with each other. This implies less dissipation in the transport of a superconductor. The BCS theory explained most of the features of the superconductors known at that time, such as (i) the discontinuity of the specific heat at the transition temperature, Tc. (ii) Involvement of the lattice via the isotope effect. (iii) Estimation of Tc and the energy gap. The value of Tc and the gap are confirmed by tunnelling experiments across metal-superconductor (M-S) or metal-insulator-superconductor (MIS) types of junctions. Giaever was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1973 for his work on these experiments. (iv) The Meissner effect can be explained within a linear response regime. (v) Temperature dependence of the energy gap, confirming gradual vanishing, which confirms a second-order phase transition. Most of the features of conventional superconductors can be explained using BCS theory. Another salient feature of the theory is that it is non-perturbative. There is no small parameter in the problem. The calculations were done with a variational theory where the energy is minimised with respect to some free parameters of the variational wavefunction, known as the BCS wavefunction.

Unconventional Superconductors: High-Tc Cuprates

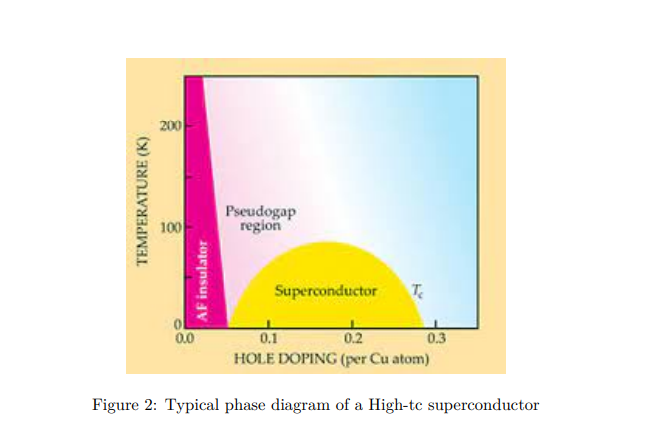

This is a class of superconductors where the two-dimensional copper oxide planes play the main role, and superconductivity occurs in these planes. Doping these planes with mobile carriers makes the system unstable towards superconducting correlations. At zero doping, the system is an antiferromagnetic insulator (see Fig. 2). With about 15% to 20% doping with foreign elements, such as strontium (Sr), etc. (for example, in La2−xSrxCuO4), the system turns superconductivity. There are two things that are surprising in this regard. (i) The proximity of the insulating state to the superconducting state; (ii) For the system initially in the superconducting state, as the temperature is raised, instead of going into a metallic state, it shows several unfamiliar features that are very unlike the known Fermi liquid characteristics. It is called a strange metal.

In fact, there are some signatures of pre-formed pairs in the ‘so-called’ metallic state, known as the pseudo gap phase. Since the starting point from which one should build a theory is missing, a complete understanding of the mechanism leading to the phenomenon cannot be understood. It remained a theoretical riddle.

Space & Physics

Researchers Develop Stretchable Material That Can Instantly Switch How It Conducts Heat

MIT engineers have developed a stretchable material heat conduction system that can rapidly switch how heat flows, enabling adaptive cooling applications.

Stretchable material heat conduction has taken a major leap forward as engineers at MIT have developed a polymer that can rapidly and reversibly switch how it conducts heat simply by being stretched. The discovery opens new possibilities for adaptive cooling technologies in clothing, electronics, and building infrastructure.

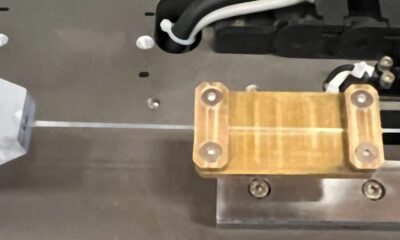

Engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed a new polymer material that can rapidly and reversibly switch how it conducts heat—simply by being stretched.

The research shows that a commonly used soft polymer, known as an olefin block copolymer (OBC), can more than double its thermal conductivity when stretched, shifting from heat-handling behaviour similar to plastic to levels closer to marble. When the material relaxes back to its original form, its heat-conducting ability drops again, returning to its plastic-like state.

The transition happens extremely fast—within just 0.22 seconds—making it the fastest thermal switching ever observed in a material, according to the researchers.

The findings open up possibilities for adaptive materials that respond to temperature changes in real time, with potential applications ranging from cooling fabrics and wearable technology to electronics, buildings, and infrastructure.

The research team initially began studying the material while searching for more sustainable alternatives to spandex, a petroleum-based elastic fabric that is difficult to recycle. During mechanical testing, the researchers noticed unexpected changes in how the polymer handled heat as it was stretched and released.

A new direction for adaptive materials

“We need materials that are inexpensive, widely available, and able to adapt quickly to changing environmental temperatures,” said Svetlana Boriskina, principal research scientist in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, in a media statement. She explained that the discovery of rapid thermal switching in this polymer creates new opportunities to design materials that actively manage heat rather than passively resisting it.

The research team initially began studying the material while searching for more sustainable alternatives to spandex, a petroleum-based elastic fabric that is difficult to recycle. During mechanical testing, the researchers noticed unexpected changes in how the polymer handled heat as it was stretched and released.

“What caught our attention was that the material’s thermal conductivity increased when stretched and decreased again when relaxed, even after thousands of cycles,” said Duo Xu, a co-author of the study, in a media statement. He added that the effect was fully reversible and occurred while the material remained largely amorphous, which contradicted existing assumptions in polymer science.

The discovery demonstrates how stretchable material heat conduction can be actively controlled in real time, allowing materials to respond dynamically to temperature changes.

How stretching unlocks heat flow

At the microscopic level, most polymers consist of tangled chains of carbon atoms that block heat flow. The MIT team found that stretching the olefin block copolymer temporarily straightens these tangled chains and aligns small crystalline regions, creating clearer pathways for heat to travel through the material.

“This gives the material the ability to toggle its heat conduction thousands of times without degrading

Unlike earlier work on polyethylene—where similar alignment permanently increased thermal conductivity—the new material does not crystallise under strain. Instead, its internal structure switches back and forth between straightened and tangled states, allowing repeated and reversible thermal switching.

“This gives the material the ability to toggle its heat conduction thousands of times without degrading,” Xu said.

From smart clothing to cooler electronics

The researchers say the material could be engineered into fibres for clothing that normally retain heat but instantly dissipate excess warmth when stretched. Similar concepts could be applied to electronics, laptops, and buildings, where materials could respond dynamically to overheating without external cooling systems.

“The difference in heat dissipation is similar to the tactile difference between touching plastic and touching marble,” Boriskina said in a media statement, highlighting how noticeable the effect can be.

The team is now working on optimising the polymer’s internal structure and exploring related materials that could produce even larger thermal shifts.

“If we can further enhance this effect, the industrial and societal impact could be substantial,” Boriskina said.

Researchers say advances in stretchable material heat conduction could significantly influence future designs of smart textiles, electronics cooling, and energy-efficient buildings.

The study has been published in the journal Advanced Materials. The authors include researchers from MIT and the Southern University of Science and Technology in China.

Researchers say advances in stretchable material heat conduction could significantly influence future designs of smart textiles, electronics cooling, and energy-efficient buildings.

Space & Physics

Physicists Capture ‘Wakes’ Left by Quarks in the Universe’s First Liquid

Scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider have observed, for the first time, fluid-like wakes created by quarks moving through quark–gluon plasma, offering direct evidence that the universe’s earliest matter behaved like a liquid rather than a cloud of free particles.

Physicists working at the CERN(The European Organization for Nuclear Research) have reported the first direct experimental evidence that quark–gluon plasma—the primordial matter that filled the universe moments after the Big Bang—behaves like a true liquid.

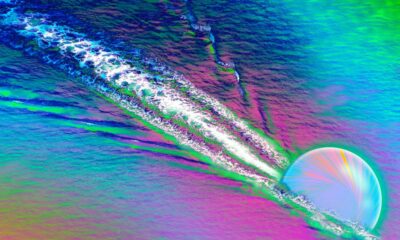

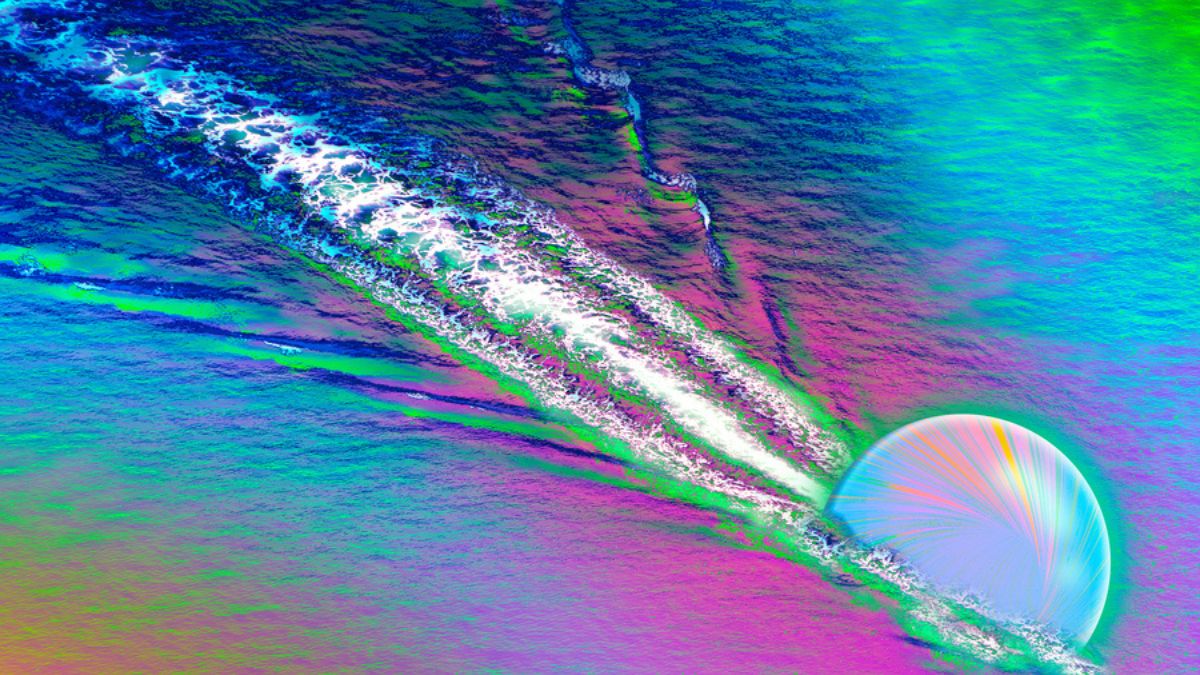

Using heavy-ion collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, researchers recreated the extreme conditions of the early universe and observed that quarks moving through this plasma generate wake-like patterns, similar to ripples trailing a duck across water.

The study, led by physicists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, shows that the quark–gluon plasma responds collectively, flowing and splashing rather than scattering randomly.

“It has been a long debate in our field, on whether the plasma should respond to a quark,” said Yen-Jie Lee in a media statement. “Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark, and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup.”

Quark–gluon plasma is believed to be the first liquid to have existed in the universe and the hottest ever observed, reaching temperatures of several trillion degrees Celsius. It is also considered a near-perfect liquid, flowing with almost no resistance.

To isolate the wake produced by a single quark, the team developed a new experimental technique. Instead of tracking pairs of quarks and antiquarks—whose effects can overlap—they identified rare collision events that produced a single quark traveling in the opposite direction of a Z boson. Because a Z boson interacts weakly with its surroundings, it acts as a clean marker, allowing scientists to attribute any observed plasma ripples solely to the quark.

“We have figured out a new technique that allows us to see the effects of a single quark in the QGP, through a different pair of particles,” Lee said.

Analysing data from around 13 billion heavy-ion collisions, the researchers identified roughly 2,000 Z-boson events. In these cases, they consistently observed fluid-like swirls in the plasma opposite to the Z boson’s direction—clear signatures of quark-induced wakes.

The results align with theoretical predictions made by MIT physicist Krishna Rajagopal, whose hybrid model suggested that quarks should drag plasma along as they move through it.

“This is something that many of us have argued must be there for a good many years, and that many experiments have looked for,” Rajagopal said.

“We’ve gained the first direct evidence that the quark indeed drags more plasma with it as it travels,” Lee added. “This will enable us to study the properties and behavior of this exotic fluid in unprecedented detail.”

The research was carried out by members of the CMS Collaboration using the Compact Muon Solenoid detector at CERN. The open-access study has been published in the journal Physics Letters B.

Space & Physics

Why Jupiter Has Eight Polar Storms — and Saturn Only One: MIT Study Offers New Clues

Two giant planets, made of the same elements, display radically different storms at their poles. New research from MIT now suggests that the key to this cosmic mystery lies not in the skies, but deep inside Jupiter and Saturn themselves.

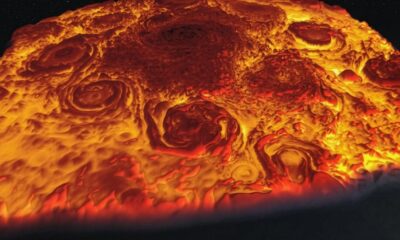

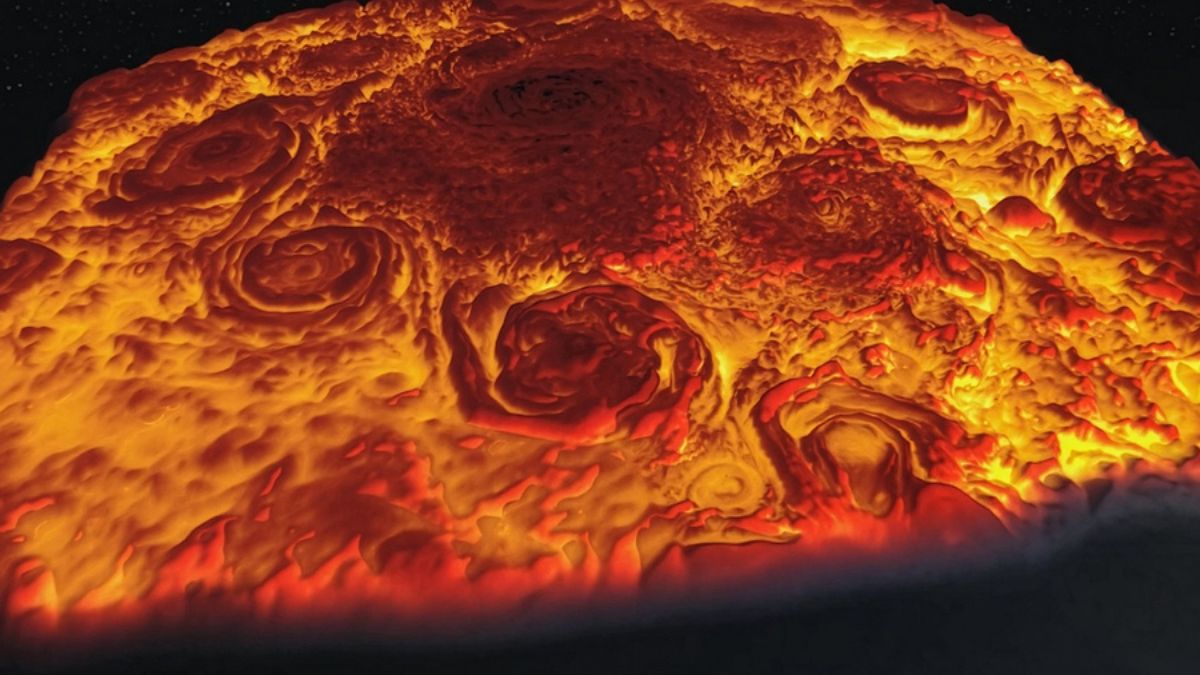

For decades, spacecraft images of Jupiter and Saturn have puzzled planetary scientists. Despite being similar in size and composition, the two gas giants display dramatically different weather systems at their poles. Jupiter hosts a striking formation: a central polar vortex encircled by eight massive storms, resembling a rotating crown. Saturn, by contrast, is capped by a single enormous cyclone, shaped like a near-perfect hexagon.

Now, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology believe they have identified a key reason behind this cosmic contrast — and the answer may lie deep beneath the planets’ cloud tops.

In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the MIT team suggests that the structure of a planet’s interior — specifically, how “soft” or “hard” the base of a vortex is — determines whether polar storms merge into one giant system or remain as multiple smaller vortices.

“Our study shows that, depending on the interior properties and the softness of the bottom of the vortex, this will influence the kind of fluid pattern you observe at the surface,” says study author Wanying Kang, assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) in a media release issued by the institute. “I don’t think anyone’s made this connection between the surface fluid pattern and the interior properties of these planets. One possible scenario could be that Saturn has a harder bottom than Jupiter.”

A long-standing planetary mystery

The contrast has been visible for years thanks to two landmark NASA missions. The Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, revealed a dramatic polar arrangement of swirling storms, each roughly 3,000 miles wide — nearly half the diameter of Earth. Cassini, which orbited Saturn for 13 years before its mission ended in 2017, documented the planet’s iconic hexagonal polar vortex, stretching nearly 18,000 miles across.

“People have spent a lot of time deciphering the differences between Jupiter and Saturn,” says Jiaru Shi, the study’s first author and an MIT graduate student. “The planets are about the same size and are both made mostly of hydrogen and helium. It’s unclear why their polar vortices are so different.”

Simulating storms on gas giants

To tackle the question, the researchers turned to computer simulations. They created a two-dimensional model of atmospheric flow designed to mimic how storms might evolve on a rapidly rotating gas giant.

While real planetary vortices are three-dimensional, the team argued that Jupiter’s and Saturn’s fast spin simplifies the physics. “In a fast-rotating system, fluid motion tends to be uniform along the rotating axis,” Kang explains. “So, we were motivated by this idea that we can reduce a 3D dynamical problem to a 2D problem because the fluid pattern does not change in 3D. This makes the problem hundreds of times faster and cheaper to simulate and study.”

The model allowed the scientists to test thousands of possible planetary conditions, varying factors such as rotation rate, internal heating, planet size and — crucially — the density of material beneath the vortices. Each simulation began with random chaotic motion and tracked how storms evolved over time.

The outcomes consistently fell into two categories: either the system developed one dominant polar vortex, like Saturn, or several coexisting vortices, like Jupiter.

The decisive factor turned out to be how much a vortex could grow before being constrained by the properties of the layers beneath it.

When the lower layers were made of softer, lighter material, individual vortices could not expand indefinitely. Instead, they stabilized at smaller sizes, allowing multiple storms to coexist at the pole. This matches what scientists observe on Jupiter.

But when the simulated vortex base was denser and more rigid, vortices were able to grow larger and eventually merge. The end result was a single, planet-scale storm — remarkably similar to Saturn’s massive polar cyclone.

“This equation has been used in many contexts, including to model midlatitude cyclones on Earth,” Kang says. “We adapted the equation to the polar regions of Jupiter and Saturn.”

The findings suggest that Saturn’s interior may contain heavier elements or more condensed material than Jupiter’s, giving its atmospheric vortices a firmer foundation to build upon.

“What we see from the surface, the fluid pattern on Jupiter and Saturn, may tell us something about the interior, like how soft the bottom is,” Shi says. “And that is important because maybe beneath Saturn’s surface, the interior is more metal-enriched and has more condensable material which allows it to provide stronger stratification than Jupiter. This would add to our understanding of these gas giants.”

Reading the interiors from the skies

Planetary scientists have long struggled to infer the internal structures of gas giants, where pressures and temperatures are far beyond what can be reproduced in laboratories. This new work offers a rare bridge between visible atmospheric patterns and hidden planetary composition.

Beyond explaining two of the Solar System’s most visually striking storms, the research could shape how scientists interpret observations of distant exoplanets as well — worlds where atmospheric patterns might be the only clues to what lies within.

For now, Jupiter’s swirling crown of storms and Saturn’s solitary hexagon may be doing more than decorating the poles of two distant giants. They may be quietly revealing the deep, unseen architecture of the planets themselves.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth3 months ago

Earth3 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet