Health

New Study Sheds Light on Life-Extending Impact of Kidney Transplants

The research finds that under the current U.S. kidney transplant system, recipients gain an average of 9.29 additional life-years

At any given time, approximately 100,000 people in the U.S. are on the waitlist for a kidney transplant, but only about one-fifth receive a new kidney each year, while others die waiting. A new study co-authored by an MIT economist adds fresh insight into this life-or-death issue, offering the most precise estimates yet of how kidney transplants extend patient lives—and how the current system might be optimized to save even more.

Published in the latest issue of Econometrica, the paper—“Choices and Outcomes in Assignment Mechanisms: The Allocation of Deceased Donor Kidneys”—is the work of Nikhil Agarwal, professor of economics at MIT; Charles Hodgson of Yale University; and Paulo Somaini of Stanford University.

“There’s always this question about how to take the scarce number of organs being donated and place them efficiently, and place them well,” said Agarwal, in a statement. He emphasized that the goal of the study is to inform, not advocate, contributing rigorous data to help shape future kidney allocation policies.

The research finds that under the current U.S. kidney transplant system, recipients gain an average of 9.29 additional life-years—a metric known as LYFT (life-years from transplantation). If kidneys were distributed randomly, that figure would fall to 7.54 years. However, by restructuring the matching system, the study estimates that the LYFT could reach as high as 14.08 years.

To reach these conclusions, the researchers used comprehensive data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, covering patients from 2000 to 2010, and tracked survival outcomes through February 2020. The study is the first of its kind to take a quasiexperimental approach, accounting for complexities such as patients’ health status and the choices they make when accepting transplant offers.

“The [previous] methodology of estimating what are the life-years benefits was not incorporating this selection issue,” said Agarwal. The study found that patients are more likely to accept kidneys from younger donors, those without hypertension, those who died from head trauma (often a sign of otherwise healthy organs), and donors with perfect tissue-type matches.

One key finding is that healthier patients tend to benefit more from transplants than sicker ones—a fact that could pose a challenge to current policies, which often prioritize patients who have spent the most time on the waitlist, or those in more dire health.

“You might think people who are the sickest and who are most likely to die without an organ are going to benefit the most from it [in added life-years],” Agarwal noted. “But there might be some other comorbidity or factor that made them sick, and their body’s going to take a toll on the new organ, so the benefits might not be as large.”

This creates a policy dilemma, as the researchers write: “Our results indicate … a dilemma rooted in the tension between these two goals”—maximizing life-years versus prioritizing the sickest patients.

Ultimately, Agarwal stresses that the study’s aim is not to advocate for a specific allocation model, but to provide tools for better policymaking. “I don’t necessarily think it’s my comparative advantage to make the ethical decisions,” he said, “but we can at least think about and quantify what some of the tradeoffs are.”

As the conversation around kidney transplant allocation continues, the study provides essential evidence to guide efforts in balancing ethics, efficiency, and patient outcomes.

Health

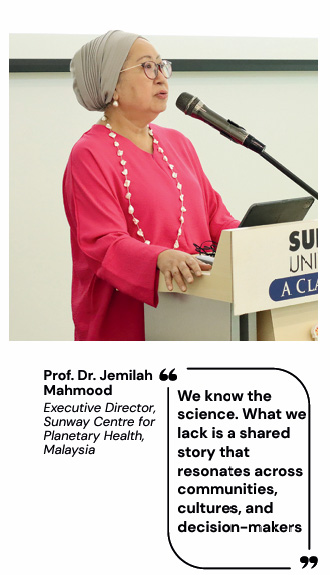

Why Planetary Health Is Failing —and How Smarter Communication Can Save It

Why Planetary Health Is Failing —and How Smarter Communication Can Save It

A major report, Voices for Planetary Health: Leveraging AI, Media and Stakeholder Strengths for Effective Narratives to Advance Planetary Health, produced by the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health at Sunway University and implemented by Internews, offers the first systematic mapping of how planetary health issues are communicated across the world. Its conclusion is clear: ineffective, fragmented communication is undermining humanity’s ability to respond to accelerating environmental and health crises. A Fractured Narrative The research team analysed 96 organizations and individuals across nine countries through interviews and social media mapping. What they found was striking. Despite decades of science showing the deep interconnections between climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss, and human health, global communication remains disjointed, inconsistent, and highly vulnerable to misinformation.

“We know the science. What we lack is a shared story that resonates across communities, cultures, and decision makers,” said Prof. Dr. Jemilah Mahmood, Executive Director of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health. Most communication efforts are siloed—environment separate from health, climate from social justice, science from lived experience. The report notes that short-term projects, scarce resources, and discipline-bound narratives prevent the creation of powerful, sustained public messages capable of shifting policy or behaviour. AI: Powerful and Dangerous One of the study’s most urgent insights concerns artificial intelligence.

AI can dramatically expand communication capacity through multilingual translation, rapid content generation, and greater accessibility. But it also creates new risks that threaten planetary health messaging. Generative AI tools can be weaponized to fabricate climate falsehoods—from bot-driven denialist content to deepfake campaigns undermining activists. AI systems also reflect structural bias; research cited in the report shows that many models privilege Western epistemologies while marginalizing Indigenous and local knowledge, contributing to what scholars term “global conservation injustices.”

And AI’s own environmental footprint cannot be ignored. Data centres already consume about 1.5 percent of global electricity, with AI-specialized facilities drawing power comparable to aluminium smelters. Training advanced models such as GPT-4 requires three to five times more energy than GPT-3—an escalation that amplifies the very planetary pressures the field is trying to solve.

Communities Most at Risk Are the Least Heard The communication gap most severely harms those already disproportionately burdened by climate-related health threats. The report highlights how marginalized communities—including low-income groups, Indigenous peoples, and communities of colour—face higher exposure to extreme heat, flooding, respiratory illnesses, vector-borne diseases, and pollution-driven health impacts.

These same communities often lack access to reliable planetary health information. Complex scientific jargon, limited translation, and English-dependent messaging create substantial barriers, leaving many without the knowledge needed to advocate for or protect themselves.Multiple studies confirm that racially and socioeconomically marginalized communities in the United States experience greater impacts from climate related health events, including extreme heat, flooding, and respiratory illnesses. Children of colour are particularly vulnerable, experiencing disproportionate health impacts from climate exposures compared to white children. The communication barriers compound these vulnerabilities.

Scientific jargon makes planetary health concepts inaccessible to general audiences, while language delivery challenges—including complex English or lack of translation—further limit reach to non-English speaking communities. Yet young people emerge as a rare bright spot. The study finds that youth activists are using digital platforms— especially Instagram, TikTok, and community networks— to push for environmental accountability. But they still confront algorithmic bias, inconsistent platform moderation, and limited institutional support.

A Blueprint for Coherent, Inclusive Communication

To fix the communication failure, the report proposes a dual framework: strategic communication aimed at policy, and democratic communication rooted in community level dialogue. It outlines six guiding principles: centering marginalized voices; treating planetary health as one integrated story; connecting disciplines and geographies; anticipating backlash and protecting communicators; adapting messages to cultural context; and working with people’s existing mental models. “Communication is not just a tool; it is a catalyst for change.

By speaking with courage, coherence, and compassion, and equipping all actors to tell inclusive stories, we can turn knowledge into action and ensure no voice is left behind,” said Jayalakshmi Shreedhar of Internews. As political rollbacks weaken environmental safeguards and six of nine planetary boundaries are already breached, the stakes could not be higher. Science alone will not save us. A compelling, coherent planetary health narrative—shared across societies—just might

Climate

The World Warms, Extreme Heat Becomes the New Normal

As global temperatures continue to rise, extreme heat is no longer a distant threat. It is a present and growing challenge that will shape health, livelihoods, and living conditions for billions of people unless decisive action is taken.

A new study from the University of Oxford has issued a stark warning about the future of global temperatures, finding that nearly half of the world’s population could be living under conditions of extreme heat by 2050. If global warming reaches 2°C above pre-industrial levels—a scenario climate scientists see as increasingly likely—around 3.79 billion people could experience dangerously high temperatures, reshaping daily life across the planet.

The findings, published in Nature Sustainability, suggest that the impacts of rising temperatures will be felt much sooner than expected. In 2010, approximately 23% of the global population lived with extreme heat; this figure is projected to rise to 41% in the coming decades. The study warns that many severe changes will occur even before the world crosses the 1.5°C limit set by the Paris Agreement.

Central African Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan, Laos, and Brazil are expected to see the largest increases in dangerously hot temperatures

According to the study, countries such as the Central African Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan, Laos, and Brazil are expected to see the largest increases in dangerously hot temperatures. Meanwhile, some of the world’s most populous nations—including India, Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and the Philippines—will have the highest numbers of people exposed to extreme heat.

The research also shows that colder countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Ireland could experience relatively dramatic increases in the number of hot days. Compared with the 2006–2016 period, warming to 2°C could lead to a 150% increase in extreme heat days in the UK and Finland, and more than a 200% increase in countries such as Norway and Ireland.

This raises concerns because infrastructure in colder regions is largely designed to retain heat rather than release it. Buildings that maximise insulation and solar gain may become uncomfortable—or even unsafe—during hotter periods, placing additional strain on energy systems and public health services.

Dr Jesus Lizana, lead author of the study and Associate Professor of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford, said the most critical changes will occur sooner than many expect. “Our study shows most of the changes in cooling and heating demand occur before reaching the 1.5°C threshold, which will require significant adaptation measures to be implemented early on,” he said. He added that many homes may need air conditioning within the next five years, even though temperatures will continue to rise if global warming reaches 2°C.

Dr Lizana also emphasised the need to address climate change without increasing emissions. “To achieve the global goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, we must decarbonise the building sector while developing more effective and resilient adaptation strategies,” he noted.

Dr Radhika Khosla, Associate Professor at Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment and leader of the Oxford Martin Future of Cooling Programme, described the findings as a wake-up call. “Overshooting 1.5°C of warming will have an unprecedented impact on everything from education and health to migration and farming,” she said, adding that sustainable development and renewed political commitment to net-zero emissions remain the most established pathway to reversing the trend of ever-hotter days.

Rising temperatures will have far-reaching impacts beyond discomfort. Demand for cooling systems is expected to rise sharply, particularly in regions that already struggle with access to electricity. At the same time, demand for heating may decline in colder countries, leading to uneven shifts in global energy use.

Dr Luke Parsons, a senior scientist at The Nature Conservancy, said the study adds to evidence that heat exposure in vulnerable communities is accelerating faster than previously predicted. He noted that communities least responsible for climate change often face the harshest impacts, underscoring the environmental justice dimensions of the crisis. Addressing the challenge, he said, will require urgent action on both mitigation and adaptation, including rapid emissions reductions and the expansion of equitable cooling solutions.

As global temperatures continue to rise, extreme heat is no longer a distant threat. It is a present and growing challenge that will shape health, livelihoods, and living conditions for billions of people unless decisive action is taken.

COP30

Health Systems ‘Unprepared’ as Climate Impacts Intensify, Experts Warn at COP30

India will require $643 billion between now and 2030 to adapt to climate change under a business-as-usual scenario

On Health Day at COP30 (November 13), global health and climate experts warned that the world is dangerously underprepared for the accelerating health impacts of climate change, calling for a dramatic scale-up of adaptation finance to protect vulnerable populations.

Speaking at a press conference hosted by Regions4, the Global Climate & Health Alliance and CarbonCopy, leaders from research institutions and national governments said climate-linked health threats — from extreme heat to wildfire smoke — are rising sharply while funding remains “colossally” insufficient.

“Each year, more than half a million lives are lost due to heat, and over 150,000 deaths are linked to wildfire smoke exposure,” said Dr. Marina Romanello, Executive Director of the Lancet Countdown. “Health systems, already stretched and underfunded, are struggling to cope with these growing pressures, and most are still unprepared for what is coming.”

Romanello added that despite the scale of the crisis, “only 44% of countries have costed their health adaptation needs, and existing finance falls short by billions. Without urgent investment, we will not be able to protect populations from escalating climate impacts.”

Adaptation gap continues to widen

The speakers described health-sector underfunding as a critical part of the broader adaptation finance gap. The latest UNEP Adaptation Gap Report estimates developing countries will need $310–365 billion annually by 2035, while the international community is still struggling to mobilise even the $40 billion Glasgow Pact Goal.

“With regards to finance, the reality is that we have a deficit that is quite colossal,” said Carlos Lopes, Special Envoy for Africa, COP30 Presidency. “Most of the efforts are from national authorities. What we need from international finance is that it must be complementary.”

Lopes cautioned that climate and health policy still operates in “multiple contested layers,” warning that unless these are aligned, “we risk losing coherence in our global response.”

Countries highlight urgent needs

Representatives from Bangladesh, Nigeria, India and Chile echoed concerns that adaptation finance is far from matching on-ground needs.

“Our adaptation financing for health is far below what is needed. The gap between what we require and what we receive is enormous,” said Md Ziaul Haque, Additional Director General, Ministry of Environment, Bangladesh. He urged multilateral finance entities to bring forward “concrete, holistic proposals that match the scale of the challenge.”

Nigeria’s challenges are equally stark. “In Nigeria, we are facing an additional 21% disease burden due to climate change… yet the adaptation finance we received in 2021–22 only met 6% of our needs,” said Oden Ewa, Commissioner for Special Duties and Green Economy Lead. He called adaptation finance a “lifeline that saves lives, strengthens communities, and protects economies.”

India outlines its adaptation burden

India also presented updated estimates of its climate adaptation needs. “India will require $643 billion between now and 2030 to adapt to climate change under a business-as-usual scenario,” said Dr. Vishwas Chitale of the Council for Energy, Environment & Water. He noted that India has already made “significant progress, spending $146 billion in 2021–2022 alone — 5.6% of GDP.”

New funding coalition signals momentum

Speakers highlighted the launch of the Climate and Health Funders Coalition, which has committed an initial $300 million annually.

“This is an encouraging signal… It shows that the world is beginning to recognise that protecting health must be at the centre of climate adaptation,” said Jeni Miller, Executive Director, Global Climate & Health Alliance.

Health at the centre of adaptation

Chile stressed the need for integrated policy approaches.

“It is vital to combine the efforts of different ministries — not only health but also transport, energy and food production — so that we generate co-benefits across sectors,” said Dr. Sandra Cortes, President of Chile’s Climate Change Scientific Committee. “A more integrated approach will allow us to improve public health, reduce emissions and create fairer, more sustainable development opportunities.”

As negotiators continue discussions in Belém, experts reiterated that adaptation finance — especially for health — must be just, equitable, accessible and prioritise the most climate-vulnerable nations. The recently proposed Belém Health Action Plan and the Global Goal on Adaptation are expected to serve as frameworks for strengthening health system resilience worldwide.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet