Space & Physics

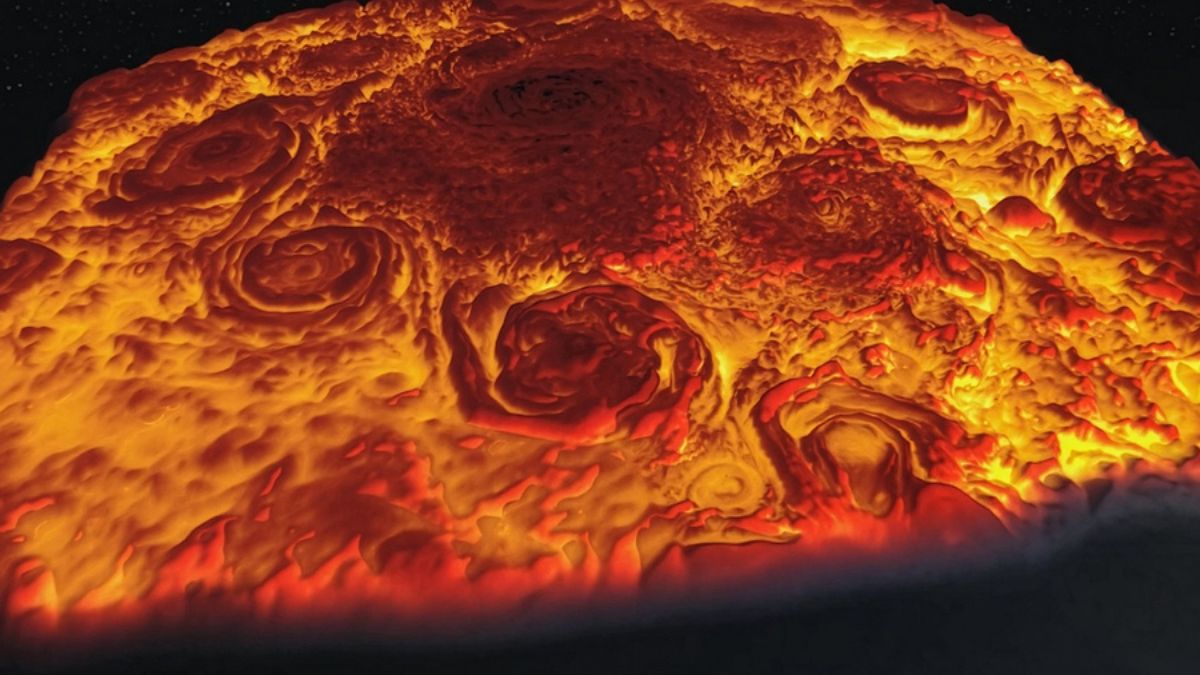

Why Jupiter Has Eight Polar Storms — and Saturn Only One: MIT Study Offers New Clues

Two giant planets, made of the same elements, display radically different storms at their poles. New research from MIT now suggests that the key to this cosmic mystery lies not in the skies, but deep inside Jupiter and Saturn themselves.

For decades, spacecraft images of Jupiter and Saturn have puzzled planetary scientists. Despite being similar in size and composition, the two gas giants display dramatically different weather systems at their poles. Jupiter hosts a striking formation: a central polar vortex encircled by eight massive storms, resembling a rotating crown. Saturn, by contrast, is capped by a single enormous cyclone, shaped like a near-perfect hexagon.

Now, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology believe they have identified a key reason behind this cosmic contrast — and the answer may lie deep beneath the planets’ cloud tops.

In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the MIT team suggests that the structure of a planet’s interior — specifically, how “soft” or “hard” the base of a vortex is — determines whether polar storms merge into one giant system or remain as multiple smaller vortices.

“Our study shows that, depending on the interior properties and the softness of the bottom of the vortex, this will influence the kind of fluid pattern you observe at the surface,” says study author Wanying Kang, assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) in a media release issued by the institute. “I don’t think anyone’s made this connection between the surface fluid pattern and the interior properties of these planets. One possible scenario could be that Saturn has a harder bottom than Jupiter.”

A long-standing planetary mystery

The contrast has been visible for years thanks to two landmark NASA missions. The Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, revealed a dramatic polar arrangement of swirling storms, each roughly 3,000 miles wide — nearly half the diameter of Earth. Cassini, which orbited Saturn for 13 years before its mission ended in 2017, documented the planet’s iconic hexagonal polar vortex, stretching nearly 18,000 miles across.

“People have spent a lot of time deciphering the differences between Jupiter and Saturn,” says Jiaru Shi, the study’s first author and an MIT graduate student. “The planets are about the same size and are both made mostly of hydrogen and helium. It’s unclear why their polar vortices are so different.”

Simulating storms on gas giants

To tackle the question, the researchers turned to computer simulations. They created a two-dimensional model of atmospheric flow designed to mimic how storms might evolve on a rapidly rotating gas giant.

While real planetary vortices are three-dimensional, the team argued that Jupiter’s and Saturn’s fast spin simplifies the physics. “In a fast-rotating system, fluid motion tends to be uniform along the rotating axis,” Kang explains. “So, we were motivated by this idea that we can reduce a 3D dynamical problem to a 2D problem because the fluid pattern does not change in 3D. This makes the problem hundreds of times faster and cheaper to simulate and study.”

The model allowed the scientists to test thousands of possible planetary conditions, varying factors such as rotation rate, internal heating, planet size and — crucially — the density of material beneath the vortices. Each simulation began with random chaotic motion and tracked how storms evolved over time.

The outcomes consistently fell into two categories: either the system developed one dominant polar vortex, like Saturn, or several coexisting vortices, like Jupiter.

The decisive factor turned out to be how much a vortex could grow before being constrained by the properties of the layers beneath it.

When the lower layers were made of softer, lighter material, individual vortices could not expand indefinitely. Instead, they stabilized at smaller sizes, allowing multiple storms to coexist at the pole. This matches what scientists observe on Jupiter.

But when the simulated vortex base was denser and more rigid, vortices were able to grow larger and eventually merge. The end result was a single, planet-scale storm — remarkably similar to Saturn’s massive polar cyclone.

“This equation has been used in many contexts, including to model midlatitude cyclones on Earth,” Kang says. “We adapted the equation to the polar regions of Jupiter and Saturn.”

The findings suggest that Saturn’s interior may contain heavier elements or more condensed material than Jupiter’s, giving its atmospheric vortices a firmer foundation to build upon.

“What we see from the surface, the fluid pattern on Jupiter and Saturn, may tell us something about the interior, like how soft the bottom is,” Shi says. “And that is important because maybe beneath Saturn’s surface, the interior is more metal-enriched and has more condensable material which allows it to provide stronger stratification than Jupiter. This would add to our understanding of these gas giants.”

Reading the interiors from the skies

Planetary scientists have long struggled to infer the internal structures of gas giants, where pressures and temperatures are far beyond what can be reproduced in laboratories. This new work offers a rare bridge between visible atmospheric patterns and hidden planetary composition.

Beyond explaining two of the Solar System’s most visually striking storms, the research could shape how scientists interpret observations of distant exoplanets as well — worlds where atmospheric patterns might be the only clues to what lies within.

For now, Jupiter’s swirling crown of storms and Saturn’s solitary hexagon may be doing more than decorating the poles of two distant giants. They may be quietly revealing the deep, unseen architecture of the planets themselves.

Space & Physics

When Quantum Rules Break: How Magnetism and Superconductivity May Finally Coexist

A new theoretical breakthrough from MIT suggests that exotic quantum particles known as anyons could reconcile a long-standing paradox in physics, opening a path to an entirely new form of superconductivity.

For decades, physicists believed that superconductivity and magnetism were fundamentally incompatible. Superconductivity is fragile: even a weak magnetic field can disrupt the delicate pairing of electrons that allows electrical current to flow without resistance. Magnetism, by its very nature, should destroy superconductivity.

And yet, in the past year, two independent experiments upended this assumption.

In two different quantum materials, researchers observed something that should not have existed at all: superconductivity and magnetism appearing side by side. One experiment involved rhombohedral graphene, while another focused on the layered crystal molybdenum ditelluride (MoTe₂). The findings stunned the condensed-matter physics community and reopened a fundamental question—how is this even possible?

Now, a new theoretical study from physicists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology offers a compelling explanation. Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers propose that under the right conditions, electrons in certain magnetic materials can split into fractional quasiparticles known as anyons—and that these anyons, rather than electrons, may be responsible for superconductivity.

If confirmed, the work would introduce a completely new form of superconductivity, one that survives magnetism and is driven by exotic quantum particles instead of ordinary electrons.

“Many more experiments are needed before one can declare victory,” said Senthil Todadri, William and Emma Rogers Professor of Physics at MIT, in a media statement. “But this theory is very promising and shows that there can be new ways in which the phenomenon of superconductivity can arise.”

A Quantum Contradiction Comes Alive

Superconductivity and magnetism are collective quantum states born from the behavior of electrons. In magnets, electrons align their spins, producing a macroscopic magnetic field. In superconductors, electrons pair up into so-called Cooper pairs, allowing current to flow without energy loss.

For decades, textbooks taught that the two states repel each other. But earlier this year, that belief cracked.

At MIT, physicist Long Ju and colleagues reported superconductivity coexisting with magnetism in rhombohedral graphene—four to five stacked graphene layers arranged in a specific crystal structure.

“It was electrifying,” Todadri recalled in a media statement. “It set the place alive. And it introduced more questions as to how this could be possible.”

Soon after, another team reported a similar duality in MoTe₂. Crucially, MoTe₂ also exhibits an exotic quantum phenomenon known as the fractional quantum anomalous Hall (FQAH) effect, in which electrons behave as if they split into fractions of themselves.

Those fractional entities are anyons.

Meet the Anyons: Where “Anything Goes”

Anyons occupy a strange middle ground in the quantum world. Unlike bosons, which happily clump together, or fermions, which avoid one another, anyons follow their own rules—and exist only in two-dimensional systems.

First predicted in the 1980s and named by MIT physicist Frank Wilczek, anyons earned their name as a playful nod to their unconventional behavior: anything goes.

Decades ago, theorists speculated that anyons might be able to superconduct in magnetic environments. But because superconductivity and magnetism were believed to be mutually exclusive, the idea was largely abandoned.

The recent MoTe₂ experiments changed that calculus.

“People knew that magnetism was usually needed to get anyons to superconduct,” Todadri said in a media statement. “But superconductivity and magnetism typically do not occur together. So then they discarded the idea.”

Now, Todadri and MIT graduate student Zhengyan Darius Shi, co-author of the study, revisited the old theory—armed with new experimental clues.

Using quantum field theory, the team modeled how electrons fractionalize in MoTe₂ under FQAH conditions. Their calculations revealed that electrons can split into anyons carrying either one-third or two-thirds of an electron’s charge.

That distinction turned out to be critical.

Anyons are notoriously “frustrated” particles—quantum effects prevent them from moving freely together.

“When you have anyons in the system, what happens is each anyon may try to move, but it’s frustrated by the presence of other anyons,” Todadri explained in a media statement. “This frustration happens even if the anyons are extremely far away from each other.”

But when the system is dominated by two-thirds-charge anyons, the frustration breaks down. Under these conditions, the anyons begin to move collectively—forming a supercurrent without resistance.

“These anyons break out of their frustration and can move without friction,” Todadri said. “The amazing thing is, this is an entirely different mechanism by which a superconductor can form.”

The team also predicts a distinctive experimental signature: swirling supercurrents that spontaneously emerge in random regions of the material—unlike anything seen in conventional superconductors.

Why This Matters Beyond Physics

If experiments confirm superconducting anyons, the implications could extend far beyond fundamental physics.

Because anyons are inherently robust against environmental disturbances, they are considered prime candidates for building stable quantum bits, or qubits—the foundation of future quantum computers.

“These theoretical ideas, if they pan out, could make this dream one tiny step within reach,” Todadri said.

More broadly, the work hints at an entirely new category of matter.

“If our anyon-based explanation is what is happening in MoTe₂, it opens the door to the study of a new kind of quantum matter which may be called ‘anyonic quantum matter,’” Todadri said. “This will be a new chapter in quantum physics.”

For now, the theory awaits experimental confirmation. But one thing is already clear: a rule long thought unbreakable in quantum physics may no longer hold—and the quantum world just became a little stranger, and far more exciting.

Society

From Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

From qubits to cultural storytelling, India’s biggest quantum science communication conclave in Ahmedabad showed how frontier science can meet people where they are. Through dialogue, demonstrations and folk art, the event reimagined how quantum knowledge reaches classrooms, communities and citizens.

The Science Communication Conference on Public Understanding of Quantum Science & Technology, widely described as India’s biggest quantum conclave, concluded on 23 December 2025 at Gujarat Science City after two days of intensive discussions, demonstrations and public-facing engagement aimed at democratising quantum knowledge.

Organised by the Gujarat Council on Science and Technology (GUJCOST) under the Department of Science & Technology, Government of Gujarat, the conference was formally inaugurated on 22 December by P. Bharathi, IAS, Secretary, DST, in the presence of senior officials, scientists, science communicators and educators from India and abroad.

P. Bharathi stressed the need to make quantum education more accessible and to build stronger public engagement so citizens can relate to quantum ideas beyond labs and classrooms. She highlighted science communication as a key bridge between advanced research and society, especially for students and educators

The second day of the conclave featured the participation of Gujarat’s Minister for Science and Technology, Arjun Modhwadia, who addressed the gathering and chaired a special session on the quantum age and society’s collective future. Emphasising the state’s long-term vision, the Minister said Gujarat believes strongly in the democratisation of quantum science, asserting that advanced scientific knowledge must reach citizens, classrooms and communities rather than remain confined to elite research spaces.

The two-day conference brought together around 200 participants, featuring keynote lectures, panel discussions, hands-on demonstrations and research presentations focused on making complex quantum concepts accessible to non-specialist audiences. International perspectives were provided by Prof. Kanan Purakayastha (UK), Dr N. T. Lan from the Vietnam Institute of Science Information, and Prof. Anjana Singh of the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology, highlighting global challenges and best practices in public engagement with quantum science.

Dr. Narottam Sahoo, Advisor and Member Secretary, Gujarat Council on Science & Technology, Department of Science & Technology, Gujarat, lauded GUJCOST’s role in popularising science, saying, “GUJCOST has been playing an instrumental role in bringing science closer to society and making it accessible to all. We will further step up such initiatives and programmes. It is a proud acknowledgement that UNESCO recognised Gujarat as a partner in the year-long quantum celebrations.”

A dynamic demonstration session on the Hands-on Quantum Education Kit, led by Dr V. B. Kamble, former Director of Vigyan Prasar, ignited curiosity among participants. Learners explored practical quantum concepts through engaging, hands-on activities, making complex ideas easier to grasp. Such interactive learning experiences help strengthen scientific temperament and inspire the next generation of innovators.

Another distinctive highlight of the programme was a folk-science puppet show presented by Dr V. P. Singh and his team from the Indian Science Communication Society (ISCOS). Blending traditional performance art with scientific ideas, the show drew strong audience attention and demonstrated how indigenous cultural forms can be effectively used to communicate abstract quantum concepts. Dr Singh beautifully bridged farmers and frontier science through a folk puppet show demonstrating how traditional art forms can communicate cutting-edge scientific ideas.

Aligned with the International Year of Quantum Science & Technology (IYQST-2025) and India’s National Quantum Mission, the conclave underscored the growing importance of science communication in preparing society for the emerging quantum era. Organisers said the conference succeeded in bridging the gap between advanced research and public understanding, reinforcing Gujarat’s position as a key hub for science outreach and quantum literacy in India.

Sessions also included interactive workshops, young researcher presentations, and dialogues on science communication methods that bridge academic science and public curiosity — reinforcing Gujarat’s aim to demystify quantum science and bring it into everyday understanding.

Space & Physics

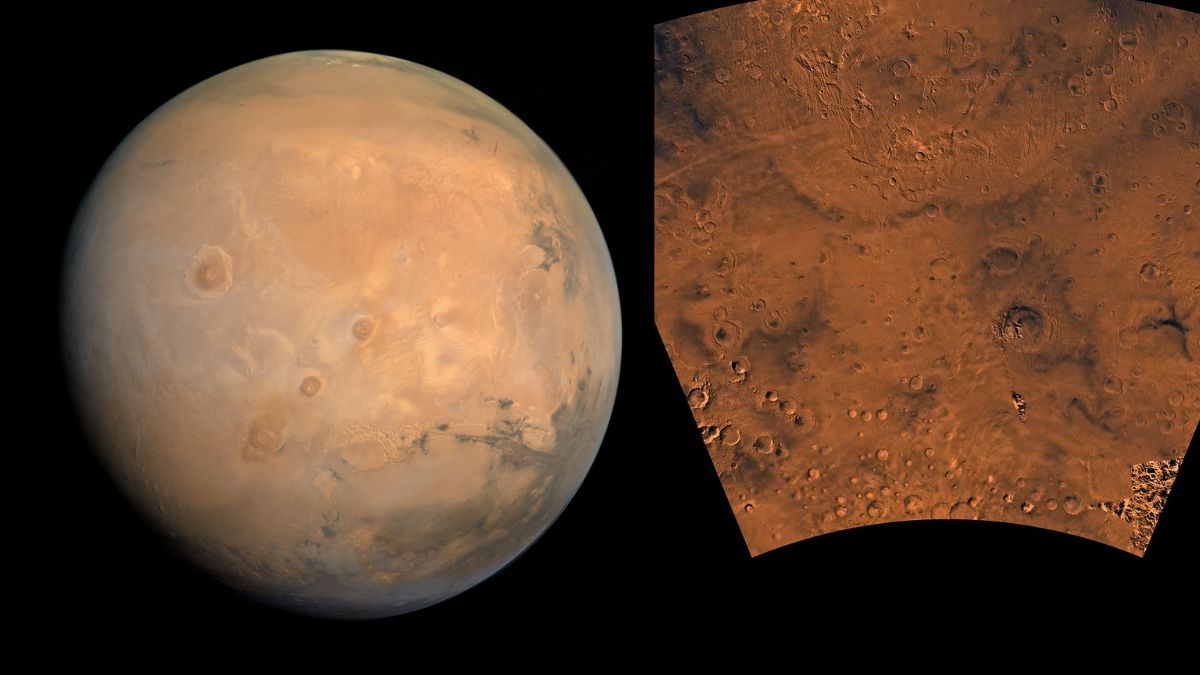

Ancient Martian Valleys Reveal Gradual Climate Shift From Warm And Wet To Cold And Icy: Study

A new study led by researchers at IIT Bombay has provided fresh evidence showing how Mars gradually transitioned from a warm, water-rich planet to a cold, icy world

A new study led by researchers at IIT Bombay has provided fresh evidence showing how Mars gradually transitioned from a warm, water-rich planet to a cold, icy world, by analysing ancient valley networks in the Thaumasian Highlands region of the Red Planet.

The findings, based on high-resolution orbital data, suggest that Mars experienced a long-term climate shift—from surface water-driven erosion during the Noachian period around four billion years ago to increasingly glacial and frozen conditions by the Hesperian period, roughly three billion years ago.

“Both these planets started with similar compositions and atmospheres. So, one of the most pressing questions is, where did all that water go, and why didn’t Mars evolve along the same direction as Earth? So, we wanted to find at what stage it lost its water,” said Alok Porwal of IIT Bombay in a statement issued by the institute.

Tracking Mars’ changing climate

The research focused on the Thaumasia Highlands, one of Mars’ most ancient geological regions, which stretches from the equator toward higher latitudes. According to the researchers, this makes it an ideal natural laboratory to study climate-driven geological changes over time.

“The Thaumasia Highlands is a region somewhat like the Indian subcontinent. It extends from the equator to higher latitudes, so it has a range of climates and geographies. It also has both very ancient geologic formations and more recent features, which gives an overall view of the planet,” Porwal said.

The team analysed more than 150 complex valley networks using datasets from NASA’s Context Camera (CTX) and Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA), the European Space Agency’s High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC), and ISRO’s Mars Orbiter Camera aboard the Mangalyaan mission. Each valley was carefully mapped to minimise errors caused by natural topographic variations.

Water-carved valleys to ice-shaped terrain

The researchers examined both qualitative and quantitative indicators to identify whether valleys were shaped by flowing water or glacial ice. Features such as fan-shaped sediment deposits and branching valley patterns pointed to fluvial erosion, while moraine-like formations, viscous flow features and ribbed terrain indicated glacial processes.

“When water is flowing, it carries heavy materials at the bottom and cuts the ground vertically. So, the shape it carves is more of a V-shaped valley. Glaciers, which have a mix of ice and debris, are heavier. When they move, they slide over the surface and create a U-shaped valley,” said Dibyendu Ghosh, the study’s first author, in the IIT Bombay statement.

Another key parameter was the angle at which valleys merge.

“When water is flowing, it follows the slope, so two valleys will flow parallel to each other and meet at an acute angle. Glaciers can move laterally, so the angles become more obtuse,” Ghosh explained.

The analysis showed that low-latitude valleys near the Martian equator were primarily shaped by flowing surface water, indicating warmer climatic conditions. In contrast, valleys at higher latitudes displayed increasing signs of fluvioglacial activity, suggesting a colder environment where ice played a growing role.

Evidence of frozen subsurface water

The study also supports the idea that much of Mars’ surface water gradually retreated underground as the planet cooled.

According to the researchers, valley formation peaked during the Noachian period between 4.1 and 3.7 billion years ago, declined during the transition to the Hesperian, and later showed stronger signatures of glacial modification and groundwater erosion.

Future exploration

While the findings offer a more coherent picture of Mars’ climatic evolution, the team noted that linking valley networks precisely to subsurface structures and geological timelines remains challenging.

Looking ahead, Porwal emphasised the need for more advanced missions to refine the planet’s climate history. “If I had a chance to suggest (for a future Mars mission), I would recommend a lander to get more geophysical data. And an orbiter with high-resolution imaging and infrared imaging capabilities to thoroughly study its geological history,” he said.

-

Society3 weeks ago

Society3 weeks agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoNew double-slit experiment proves Einstein’s predictions were off the mark

-

Earth2 months ago

Earth2 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP302 months ago

COP302 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Women In Science3 months ago

Women In Science3 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Space & Physics1 month ago

Space & Physics1 month agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date