Society

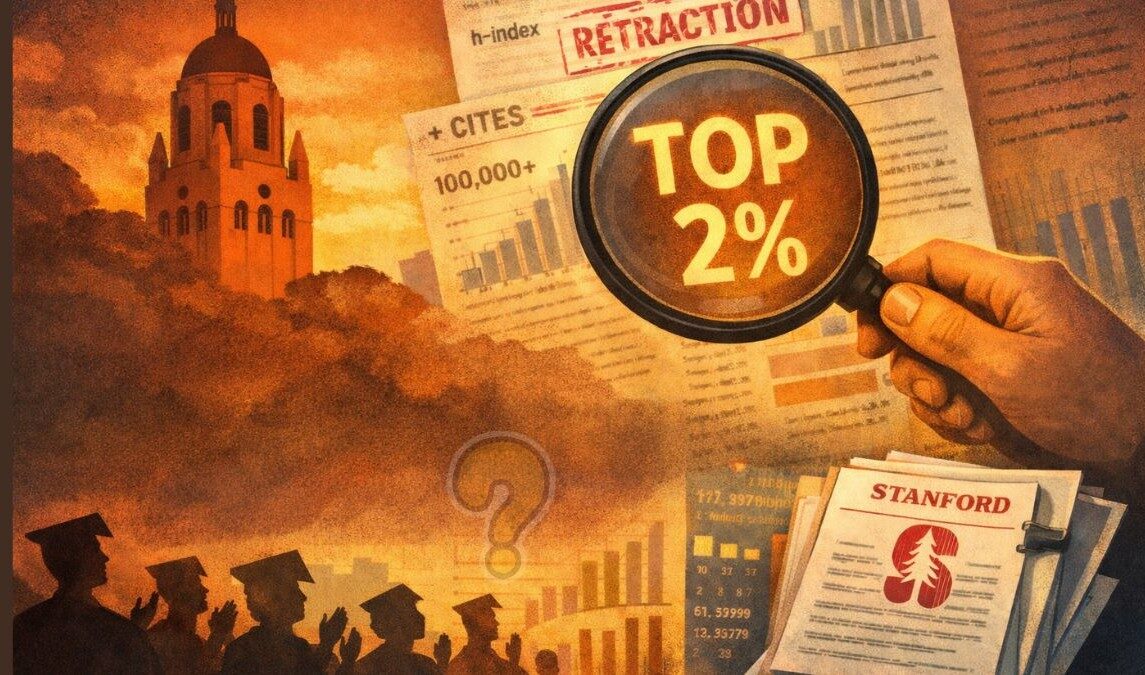

Why the ‘Stanford Top 2% Scientists’ Label Is Widely Misrepresented

What began as a bibliometric dataset has quietly transformed into a badge of prestige across Indian academia…

Last month, a friend sent me a social media card celebrating a science researcher she knows personally. The card was crisp, congratulatory, and emphatic: the researcher had been included in the “Top 2% Stanford Scientists” list. My friend went a step further. In a lecture soon after, she cited the inclusion as proof that the researcher had made it to a prestigious list of Stanford University—a global stamp of academic excellence.

There was no doubt about the researcher’s merit. She is a solid scientist, respected in her field. But the framing stayed with me. Over the next few weeks, I began noticing similar announcements everywhere—university press releases, institutional websites, LinkedIn posts, WhatsApp forwards. The pattern was strikingly uniform: “Our faculty member named in Stanford University’s Top 2% Scientists list.” The implication was clear. Stanford had selected. Stanford had ranked. Stanford had endorsed.

But had it?

That question, according to Achal Agrawal of India Research Watch, is precisely where Indian media reporting has fallen short. “There is no official confirmation that Stanford University endorses this list,” he said while speaking at a recent science conference conducted by SJAI in Ahmedabad, India. “Yet the list is routinely presented as a Stanford ranking, without even basic verification.”

What the List Actually Is

The list commonly referred to as the “Stanford list of top 2% scientists” is based on a large-scale citation analysis developed by a group of researchers led by Professor John P. A. Ioannidis, who is affiliated with Stanford University. It draws on data from Scopus, Elsevier’s citation database, and ranks researchers using a composite bibliometric indicator that combines citations, h-index, co-authorship patterns, and related metrics.

Importantly, this is not an award, nor a peer-reviewed selection process. It is an algorithmic dataset. According to standardized science-wide citation databases created by Ioannidis and collaborators at Stanford, the “Top 2%” list compiles researchers based on composite citation metrics from Scopus — identifying highly cited authors within each field — but it is not a ceremonial award or formal Stanford ranking.

Crucially—and almost never mentioned in celebratory coverage—the dataset itself carries explicit caveats. “The list itself says that it should not be used for evaluation,” Experts pointed out. “That warning is written in the methodology section of the paper.”

What Is Rarely Reported

One of the most striking omissions in media coverage is that the dataset includes a separate column for retractions.

“There is an explicit column for retractions,” Agrawal noted. “There are people in the list with over 100 retractions. In some cases, nearly half of the people being celebrated by universities have retracted papers.”

Despite this, universities across India have published newspaper advertisements highlighting how many faculty members they have in the “top 2% list,” without acknowledging the list’s internal flags or limitations.

This selective storytelling, Agrawal argued, reflects a broader failure of journalistic scrutiny. “It is the media’s duty to question,” he said. “Instead, we have seen hundreds of articles simply reproducing the claim.”

How the Narrative Spreads

The pattern repeats itself across regions. Headlines announcing that “three people from Rajasthan” or “two people from Hyderabad” have made it to the top 2 percent appear regularly—almost always without context. “Unquestioning, putting it as the Stanford top 2% list,” Agrawal observed.

The result is a system where visibility replaces verification, and repetition stands in for rigour.

Rankings, Prestige, and the Illusion of Success

This uncritical acceptance of rankings is not limited to the Stanford list. Agrawal pointed to a striking example from global university rankings. “Times Higher Education once put IISc at 60th position in India in research quality,” he said. “Anyone would laugh at that. IISc is undoubtedly one of the best institutions in the country.”

Yet headlines rarely reflect such scepticism. Instead, rankings are framed as national achievements. Even political leadership has cited rising numbers of Indian universities in global rankings as evidence of progress.

“We need to change our measure of success”

“That cannot be a measure of success,” Agrawal warned. “If that is the measure we accept, then the distortions we see today are the outcome.”

A Call for Media Responsibility

The problem, experts argue, is not the existence of bibliometric datasets, but how they are communicated and consumed. Citation-based lists can serve useful analytical purposes when interpreted carefully. But when they are elevated into symbols of institutional excellence, without context or caveats, they risk misleading both the public and policymakers.

“We need to change our measure of success,” Agrawal concluded. “And the first step is for the media to stop reporting rankings as trophies, and start treating them as data that must be interrogated.”

The truth about the “Top 2% Scientists” list, then, is not that it is meaningless—but that its meaning has been repeatedly overstated. Used responsibly, it is one dataset among many. Used uncritically, it becomes a powerful illusion of prestige.

Climate

IEA Ministerial 2026: Global Energy Leaders Expand Ties, Push Critical Minerals Security

At the IEA Ministerial Meeting in Paris, 54 countries backed expanded membership talks with Brazil, India, Colombia and Viet Nam, while strengthening cooperation on critical minerals and clean energy security.

Global energy leaders convened in Paris this week for the International Energy Agency’s Ministerial Meeting, underscoring the agency’s expanding role in shaping international cooperation at a time of rising demand, geopolitical tensions, and accelerating energy transitions.

The two-day gathering drew senior government representatives from a record 54 countries, around 40 of them at ministerial level. Executives from 55 companies — representing a combined market capitalisation of $14 trillion — joined leaders of intergovernmental organisations in what became the largest Ministerial Meeting in the agency’s history.

At the heart of the discussions was a clear message: energy security, affordability and sustainability can no longer be pursued in isolation. They require deeper multilateral coordination, stronger data systems, and expanded institutional alliances.

Expanding the IEA Family

Member governments unanimously agreed to move forward on strengthening institutional ties with Brazil, Colombia, India and Viet Nam. In a major step, Colombia was invited to become the IEA’s 33rd Member. Brazil was invited to begin the process toward full membership following a request from its government. Ministers also welcomed recent progress in discussions with India regarding its request for full membership. Viet Nam joined as the newest Association country in the IEA Family.

The expansion significantly alters the geometry of global energy governance. With these additions, the IEA Family’s share of global energy consumption now exceeds 80%, up from less than 40% a decade ago — reflecting a profound shift in the agency’s global reach.

“This Ministerial Meeting, our largest ever, affirmed the immense value of the IEA at a moment when global energy demand is rising and the challenges facing the energy system are intensifying. In this context, our wide range of objective data and analysis is more important than ever,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol.

“In a strong step forward for global energy governance, key countries such as Brazil, Colombia, India and Viet Nam are strengthening their ties with the IEA. This puts the IEA Family’s share of global energy use at more than 80%, up from less than 40% ten years ago. With major energy issues high on the international agenda, we stand ready to support governments with the insights they need to plan for the future, helping leaders deliver on their goals of ensuring greater energy security, affordability and sustainability.”

Deputy Prime Minister Sophie Hermans of the Netherlands, who chaired the Ministerial, framed the discussions in terms of resilience amid uncertainty.

“These two days in Paris have reaffirmed how essential energy is to our daily lives – it is the invisible driving force behind everything we do. Under the umbrella of knowledge of the International Energy Agency, we have once again seen that international cooperation is key,” she said. “Our priority is clear: secure, affordable and sustainable energy – and resilient systems that can endure in an uncertain world.”

In a video address opening the meeting, French President Emmanuel Macron emphasised the IEA’s analytical leadership. “Through its in-depth analyses, and the technical expertise of its team, the IEA, under the leadership of its Executive Director Fatih Birol, plays an essential role. It enlightens us to help us guarantee our energy security and steer the energy transition.”

Beyond institutional expansion, the Ministerial marked a strong endorsement of deeper cooperation on critical minerals — increasingly viewed as the backbone of clean energy technologies.

In a special declaration, Ministers backed expanding collaboration under the IEA Critical Minerals Security Programme to address mounting risks to global supply chains. They called for strengthened data tools, collaborative exercises and clearer guidance on measures such as stockpiling, aimed at diversifying supply chains and building resilience against supply shocks.

Clean Cooking and Energy Access

Member countries also approved the integration of the Clean Cooking Alliance into the IEA, positioning the agency as the principal multilateral forum for advancing clean cooking solutions. The move seeks to accelerate access for the more than two billion people worldwide who still lack clean cooking technologies.

The integration comes ahead of the IEA’s second Summit on Clean Cooking in Africa, scheduled for July 2026 in Nairobi, where governments and industry leaders are expected to review progress since the inaugural 2024 summit and outline new financing and policy pathways.

Energy Security in the Age of Electricity

Two high-level dialogues during the Ministerial focused on safeguarding energy security in what officials termed the “Age of Electricity,” and on supporting Ukraine’s energy system amid ongoing disruptions. Ukrainian First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Energy Denys Shmyhal participated in discussions on rebuilding and securing Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

As energy demand continues to climb and transition pathways grow more complex, the IEA’s expanding membership and programme scope suggest that multilateral coordination — once largely confined to oil security — is now being repositioned as the backbone of a rapidly electrifying and mineral-intensive global energy system.

Earth

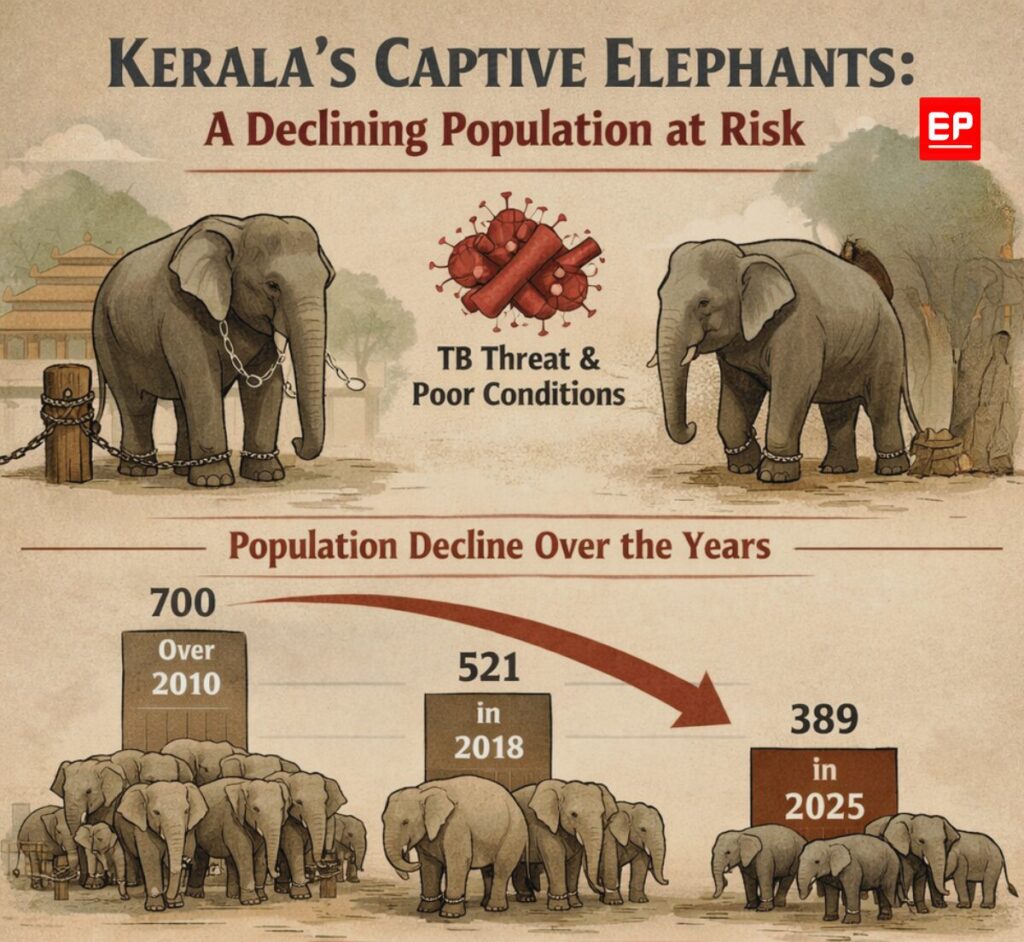

EP Investigation: Hidden Epidemic, Tuberculosis Spreads Among Kerala’s Captive Elephants

An EP Investigation into tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants reveals human transmission risks, weak screening systems, and urgent policy gaps.

Tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants has become a silent but persistent threat, driven largely by human-to-animal transmission, chronic stress, and systemic failures in veterinary public health. An EdPublica (EP) Investigation reveals how the absence of routine screening, weak governance, and prolonged neglect could turn a preventable disease into a far larger crisis in the years ahead.

By Lakshmi Narayanan | EP Investigation

Tuberculosis is quietly spreading among Kerala’s captive elephants, sustained not by wildlife exposure but by human contact, chronic stress, and systemic neglect. Long treated as a marginal veterinary issue, the disease represents a serious and largely ignored public health and animal welfare crisis—one that experts warn could intensify in the coming years if left unaddressed.

Kerala hosts one of the largest populations of captive Asian elephants in India, housed by temples, private owners, and festival organisers. According to a Forest Department survey concluded in February 2025, the state currently has 389 captive elephants, marking a steady decline from 521 in 2018 and over 700 in 2010, with the majority now owned by private individuals. This sharp reduction over the past decade reflects broader stresses within the captive elephant system, including ageing animals, declining ownership viability, and chronic health concerns.

Within this shrinking population, tuberculosis is neither new nor rare; it is endemic. Historical veterinary records and animal welfare documentation indicate that in earlier years, TB may have contributed to as many as 25 captive elephant deaths annually. Yet in recent times, detailed and transparent reporting on TB-related infections and fatalities has largely disappeared from public view, creating a misleading impression that the risk has diminished when, in reality, surveillance itself has weakened.

This absence of attention does not signal reduced risk. Tuberculosis is a slow, insidious disease that can remain latent or undiagnosed for years. Without mandatory screening or transparent surveillance, infection can circulate undetected within captive elephant populations—allowing animals to suffer prolonged illness and potentially function as silent reservoirs of infection.

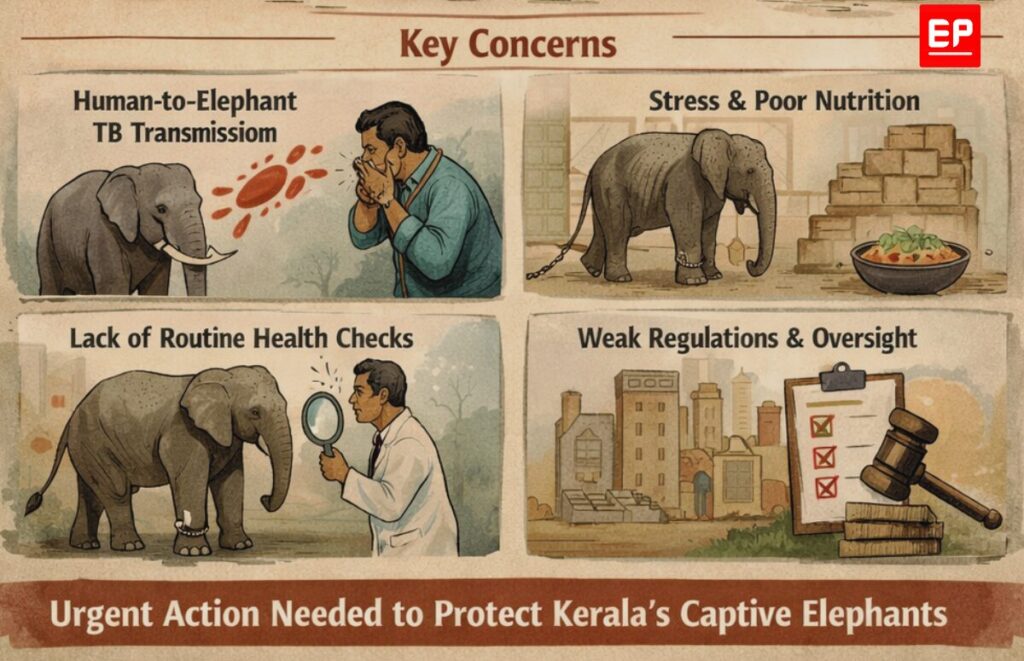

The persistence of tuberculosis among captive elephants is not accidental. It is the result of a convergence of vulnerabilities: constant exposure to infected humans, immune suppression driven by captivity-related stress, and systemic failures in veterinary public health governance. Together, these factors have created ideal conditions for a preventable disease to endure—largely unseen, and largely unchallenged.

The Human–Elephant Interface: A Critical Transmission Pathway

The primary route of TB transmission among Kerala’s captive elephants is reverse zoonosis: the spread of infection from humans to animals. The causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a human-adapted pathogen transmitted through respiratory aerosols. In settings where elephants live and work in close proximity to people, this pathway becomes epidemiologically decisive.

Mahouts and handlers represent the most significant source of chronic exposure. Their daily routines—feeding, bathing, training, and transporting elephants—require prolonged, close physical contact. If a handler carries an active or latent TB infection, the opportunity for transmission to the animal is constant and cumulative.

In addition to handlers, the general public constitutes a secondary but important exposure source. Kerala’s festival culture routinely places elephants amid dense crowds, often for extended periods. These gatherings create intermittent but high-volume opportunities for transmission from undiagnosed or untreated individuals within the broader population. Together, these human reservoirs ensure that captive elephants are rarely insulated from the pathogen. Yet exposure alone does not fully explain disease persistence. The risk of infection is significantly magnified by conditions that undermine the elephants’ immune defenses.

“Tuberculosis in captive elephants is a severe and often underestimated disease. What is seen during post-mortem examinations is extensive, chronic organ damage that reflects prolonged suffering rather than sudden illness. These findings are consistent with long-term exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and delayed detection, Dr. Arun Vishvanathan, a veterinary expert based in Kerala’s Palakkad district, tells EdPublica.

“From a medical and public health perspective, this condition is particularly concerning because it is largely driven by human-to-animal transmission. Elephants living in close, continuous contact with people—especially under stressful captive conditions—experience immune suppression, which allows the infection to progress unchecked. This is not an unavoidable disease; it is a preventable one. Without routine screening of both handlers and elephants, early diagnosis, and strict biosecurity measures, such cases will continue to occur, resulting in needless animal suffering and ongoing public health risk,” Dr. Arun Vishvanathan adds.

Stress, Captivity, and Immune Compromise

Captive environments impose profound physiological and psychological stress on elephants, a species evolved for expansive movement, complex social structures, and environmental autonomy. Confinement to restricted spaces, prolonged chaining, limited exercise, and forced participation in noisy, crowded festivals all contribute to chronic stress.

Scientific evidence across species demonstrates that sustained stress suppresses immune function. In elephants, this immunosuppression reduces resistance to opportunistic infections such as TB and increases the likelihood that latent infections will progress to active disease.

Crowding further compounds the problem. Elephants housed in close quarters or transported frequently between venues are exposed not only to more humans but also to environments conducive to airborne disease transmission. In these conditions, respiratory pathogens can spread efficiently, especially when animals are already physiologically compromised.

”Tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants spreads primarily through close, repeated contact with infected humans, and is sustained by conditions that weaken the animals’ natural defenses. Unlike many wildlife diseases, this is not an infection originating in forests—it is largely a human-driven disease cycle. Mahouts and handlers are the most significant transmission source. Daily activities such as feeding, bathing, chaining, and transport require close physical proximity, often for hours at a time. If a handler has active or undiagnosed TB, the elephant is repeatedly exposed to infectious aerosols,” says Manuprasad, an elephant welfare worker from Thrissur.

Festival crowds and tourists create additional exposure. During temple festivals and public events, elephants are surrounded by dense crowds, sometimes for entire days. In these settings, even brief exposure to multiple infected individuals can result in infection.

Systemic Gaps in Veterinary Public Health

Perhaps the most critical vulnerability lies not in biology but in governance. Kerala lacks a standardized, mandatory TB screening programme for captive elephants. As a result, infected animals—many of them asymptomatic—remain undiagnosed for years. This failure in routine surveillance effectively blinds any meaningful public health response and allows elephants to function as silent reservoirs of infection.

Experts warn that tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants could expand if mandatory screening and biosecurity measures are not urgently implemented.

Nutritional inadequacy is another systemic issue. Economic pressures within the temple and festival ecosystem often translate into suboptimal feeding regimes. Poor nutrition weakens immune responses, lowering the infectious dose required for TB to establish and spread.

Compounding these challenges is a widespread lack of awareness among elephant owners and handlers regarding TB transmission and prevention. Clear, enforceable biosecurity protocols—covering quarantine, treatment, and movement restrictions for TB-positive animals—are largely absent or inconsistently applied. Without such measures, even identified cases pose an ongoing risk to other elephants and to humans.

”As an animal rights and welfare activist, I have personally witnessed the post-mortem of an elephant affected by tuberculosis, and it was deeply distressing. The extent of internal damage revealed the severe and prolonged suffering this animal endured—far beyond what most people realize. Seeing such devastation in an animal of immense strength and dignity is heartbreaking,” explains Ambili Purackal, founder of DAYA, a Kerala-based NGO known for its proactive role in the state’s animal rights movement.

What makes this suffering even harder to accept is that it is largely the result of human exposure. Elephants do not face tuberculosis at these levels in the wild; they contract it through forced, prolonged contact with humans under stressful captive conditions that weaken their immunity. This is not just a veterinary concern but a moral one. These elephants are silent victims of preventable disease, and their suffering is a consequence of human neglect and systemic failure,” Ambili Purackal says.

Secondary and Less-Documented Risks

While human-to-elephant transmission remains the dominant concern, other pathways cannot be entirely dismissed. Interactions with domestic livestock or wildlife in shared environments may contribute to transmission chains, though this remains poorly documented in the Indian context. These ancillary risks further underscore the need for comprehensive epidemiological research.

A Convergence of Vulnerabilities

Taken together, the vulnerabilities facing Kerala’s captive elephants form a self-reinforcing cycle. Constant exposure to a human TB reservoir, chronic immune compromise driven by captivity-related stress and poor nutrition, and systemic failures in disease detection and control create ideal conditions for TB persistence.

Breaking this cycle will require a multi-layered public health approach—one that integrates routine screening, improved nutrition, handler health monitoring, and enforceable management protocols. Without such intervention, tuberculosis will remain a silent epidemic, exacting a slow but devastating toll on one of Kerala’s most culturally significant animal populations.

Silence, in this case, is not neutrality—it is risk.

What Needs to Change

Addressing tuberculosis among Kerala’s captive elephants requires coordinated action across animal welfare, public health, and governance. Experts and welfare workers interviewed by EdPublica point to the following urgent priorities:

1. Mandatory TB Screening

· Routine, standardised tuberculosis testing for all captive elephants

· Regular TB screening for mahouts, handlers, and caretakers

· Immediate isolation and treatment protocols for positive cases

2. Handler Health Monitoring

· Integration of mahout health checks into public TB control programmes

· Confidential diagnosis and treatment access to reduce stigma and underreporting

3. Improved Living Conditions

· Reduced chaining and confinement

· Adequate daily exercise and social interaction

· Limits on festival exposure, crowd density, and noise-related stress

4. Nutritional Standards

· Enforced minimum nutrition guidelines

· Regular veterinary audits to ensure immune-supportive diets

5. Biosecurity and Movement Controls

· Quarantine protocols for newly acquired or transferred elephants

· Restrictions on inter-district or inter-state movement of TB-positive animals

6. Transparent Reporting and Oversight

· Publicly accessible data on TB cases and outcomes

· Independent audits of temple and private elephant management practices

7. Interdepartmental Coordination

· Formal collaboration between forest, animal husbandry, and public health departments

· Recognition of TB in captive elephants as a One Health issue—linking human, animal, and environmental health

Some sources in this investigation have requested anonymity due to professional or personal safety concerns. Their identities are known to EdPublica and their statements have been independently verified.

Climate

Could Global Warming Make Greenland, Norway and Sweden Much Colder?

A Nordic Council report warns that global warming could make Norway colder if the Atlantic ocean circulation collapses, triggering severe climate impacts.

Global warming is usually associated with rising temperatures—but a new Nordic report warns it could drive parts of northern Europe into far colder conditions if a major Atlantic ocean current collapses.

Greenland, Norway and Sweden could experience significantly colder climates as the planet warms, according to a new report by the Nordic Council of Ministers that examines the risks linked to a possible collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

The report, A Nordic Perspective on AMOC Tipping, brings together the latest scientific evidence on how global warming is slowing the AMOC—one of the world’s largest ocean circulation systems, responsible for transporting heat from the tropics to the North Atlantic. While a full collapse is considered unlikely, the authors warn that it remains possible even at relatively low levels of global warming, with potentially disruptive consequences for northern countries.

The Reversal

If the circulation were to weaken rapidly or cross a tipping point, the report notes, northern Europe could cool sharply even as the rest of the world continues to warm. Such a reversal would have wide-ranging effects on food production, energy systems, infrastructure, and livelihoods across the Nordic region.

“The AMOC is a key part of the climate system for the Nordic region. While the future of the AMOC is uncertain, the potential for a rapid weakening or collapse is a risk we need to take seriously,” said Aleksi Nummelin, Research Professor at the Finnish Meteorological Institute, in a media statement. “This report brings together current scientific knowledge and highlights practical actions for mitigation, monitoring and preparedness.”

A climate paradox

The AMOC plays a central role in maintaining the relatively mild climate of Northern Europe. As global temperatures rise, melting ice from Greenland and increased freshwater input into the North Atlantic are expected to weaken this circulation. According to the report, such changes could reduce heat transport northwards, leading to colder regional conditions—particularly during winter—even under a globally warming climate.

Scientists caution that the impacts would not simply mirror gradual climate change trends. Instead, an AMOC collapse could trigger abrupt and uneven shifts, including expanded sea ice, stronger storms, altered rainfall patterns, and rising sea levels along European coastlines. Some of these impacts would occur regardless of when or how quickly the circulation weakens.

The report also highlights global ripple effects. A slowdown of the AMOC could shift the tropical rain belt southwards, with potentially severe consequences for monsoon-dependent regions such as parts of Africa and South Asia, underscoring that AMOC tipping is not a regional concern alone.

Calls for precaution and preparedness

Given the uncertainty surrounding when—or if—the AMOC might cross a critical threshold, the report urges policymakers to adopt a precautionary approach. It stresses that any additional global warming, and prolonged overshoot of the 1.5°C target, increases the risk of triggering a collapse.

Key recommendations include accelerating emissions reductions, securing long-term funding for ocean observation networks, and developing an early warning system that integrates real-world measurements with climate model simulations. The authors argue that such systems should be embedded directly into policymaking to enable rapid responses.

The report also calls for climate adaptation strategies that account for multiple futures—including scenarios in which parts of Northern Europe cool rather than warm. It emphasises that AMOC collapse should be treated as a real and significant risk, requiring comprehensive risk management frameworks across climate, ocean, and disaster governance.

Science driving policy attention

The findings were developed through the Nordic Tipping Week workshop held in October 2025 in Helsinki and Rovaniemi, bringing together physical oceanographers, climate scientists, and social scientists from across Nordic and international institutions. The initiative was partly motivated by an open letter submitted in 2024 by 44 climate scientists, warning Nordic policymakers that the risks associated with AMOC tipping may have been underestimated.

By consolidating current scientific understanding and translating it into policy-relevant recommendations, the report aims to shift AMOC collapse from a theoretical concern to a concrete risk requiring immediate attention.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth3 months ago

Earth3 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet