Society

Water is the new ‘spice’ of space travel

As we enter a new space age scripting history, we may be yet to come to grasps with the politics of space.

“Power over spice, is power over all,” said an ominous voice (In an alien sounding language) as words then took shape on the theater screen, at last week’s release of Dune: Part Two (2024), a sci-fi adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 eponymous novel. To give a basic premise of its fictional universe, humanity has become a space-faring race, inhabiting planets orbiting distant stars. In Herbert’s Dune, humanity accessed a novel spice found only in a barren, desert planet called Arrakis.

As much as it works to spice up food, it functions as a psychotropic drug as well. In fact, consuming too much spice can help you enable bend space-time itself like a wormhole, providing prescience to enable safe passage between the stars.

It may just be a novel that recently got adapted into a two-parter (perhaps it’s a trilogy if Dune Messiah is adapted too) movie, but the story vibes with a lot of chatter in our society too.

Elon Musk, for instance, envisions humanity to colonize Mars with 1 million people. He tweeted at one point on the need to avoid the Great Filter, and similarly embrace our destiny as it were of becoming a space-faring species.

Much like spice melange in Dune, the Artemis program hopes to demonstrate how water on the moon can fuel dreams of space colonization.

It may just be chatter and hype, but last week saw Intuitive Machine’s Odyssey mission end all too soon, after a rough landing in the rugged lunar terrain, leaving it tipped over its side. That mission may have ended all too soon. However, it surely would be replaced by another robotic exploration mission that Intuitive Machines’ contracted to do as part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS). And more missions will follow up to set the stage for Artemis III’s planned lunar soft landing in 2026. That mission would presumably see the first astronauts to set boots on the moon since Apollo 17.

Much like spice melange in Dune, the Artemis program hopes to demonstrate how water on the moon can fuel dreams of space colonization. Simple electrolysis of water can yield molecular hydrogen and oxygen on earth. On the moon, it’s easier to launch a rocket with even limited fuel compared to earth, since lunar gravity is one-sixth of the earth. In outer space, water as fuel can help alleviate the cost burden inherent in human spaceflight.

The spice is actually the excreta of the native gigantic sandworms of Arrakis. Credit: Astronimation / Wikimedia

Regulating space

Dune explored themes beyond technological supremacy inherent with spice. In fact, what made the book so popular was how it imagined humanity 8,000 years from now ruled by an ‘Emperor of the Known Universe’ with their nobility like in feudal societies. However, the bearers of the spice melange held prescience abilities in addition to folding space for interstellar travel. The Spacing Guild as they were known in the novel, could see events unfold like no one could. They weren’t noble, despite being elevated to nobility status. The politics of space travel isn’t a subject that’s not been broached in science fiction, but perhaps we don’t talk as much of it in our real world as we ought to.

The universe in Dune would see wars unfold time and again. However, what’s important is how space agencies in our world – NASA, ESA, ISRO, CNSA, JAXA, Roscosmos and now many from the developing world contest for space in space. The Donald Trump administration brought the Artemis Accords to bear, and now has seen 36 countries become signatories for peaceful use of outer space. This isn’t an international mandate, since the Chinese and the Russians say they have no plans to sign yet – calling it ‘US-centric’ in designs.

What’s at stake now for space exploration is the question of whether anyone own property in space. Well, the UN’s Office for Outer Space Affairs says no, referring to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty signed and thus agreed upon that space is international property. However, it doesn’t state how the resources can be utilized in other respects. Soil samples in the moon collected by Apollo have been distributed by the US to other nations. Space research and the space community so far has always been known to be cordial, seemingly escaping the touches of politics. Seemingly.

The politics of space travel isn’t a subject that’s not been broached in science fiction, but perhaps we don’t talk as much of it in our real world as we ought to.

Water ice exists as just on average 500 parts per million in the lunar regolith (in higher latitudes) – drier than even the driest sands on earth. Though to a spectrometer on a lunar orbiter, that’s the signature for water, although not in drinkable form. However, water ice can’t be directly electrolyzed without essentially mining that water much like we do on earth. Perhaps in a not so distant future, space mining could be a thing perhaps on asteroids where, much like the Spacing Guild in Dune, space companies could send diggers. The ‘Emperor of the Known Universe’ though isn’t really well-known at this point. It’s more like the many Great Houses in the novel, with Dukes and Duchesses scheming their own ambitions, to dominate the spice and control planet Arrakis.

The space sector isn’t regulated well enough as technology seems to keep abreast of everything else. Water’s the new oil of space. There isn’t too much of it either. However, mining anything in space would come at the cost of violating UN designated sustainability goals. Mining water from the moon in excess could cause some long lasting damage to the soil.

Here’s an ethical outlook. When we think and dream of human spaceflight exploration and all that, we also carry with it our character as a species. Although polluting space may not affect earth physically, doesn’t it deem a society with little moral rectitude if it ever was to happen? Wouldn’t the wrong people be incentivized? Shouldn’t we care for principles we believe in on earth and apply them to space?

As we enter the New Space Age, we perhaps remember that dialogue, “Power over spice, is power over all.” Dune’s nihilistic at best, although we can do better to not act on that urge to control and dominate. Perhaps, we can treat outer space too with some respect and the awe we always had for it.

EDUNEWS & VIEWS

India Emerging as a Global Education Hub as International Student Numbers Set to Rise Rapidly: QS Report

A QS report forecasts international student enrolments in India to grow 8% annually to 2030, positioning the country as a rising global education hub while highlighting challenges in reputation, employability, and infrastructure.

India international students are expected to grow rapidly over the next decade, with a new QS report forecasting annual growth of about 8% through 2030.

India is poised to strengthen its position as a major global education destination, with international student enrolments projected to grow steadily in the coming years, according to a new report by global higher education analytics firm QS Quacquarelli Symonds.

The report, QS Global Student Flows: India 2026, forecasts that inbound student numbers will grow by around 8% annually through 2030, starting from an estimated base of 58,000 international students in 2025.

The analysis highlights a shifting landscape in global student mobility. Tightening visa regulations and rising costs in traditional study destinations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia are encouraging many international students to consider more affordable and accessible alternatives — with India increasingly emerging as a strong contender.

Regional Demand Driving Growth

South Asia remains the largest source of international students for India. Countries such as Nepal and Bangladesh together account for more than 30% of incoming students, and Nepal’s numbers alone are projected to grow at roughly 11% annually.

Demand is also rising significantly from Africa. Student flows from Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to grow at around 6% annually, driven by expanding youth populations and limited higher education capacity in many African countries. Zimbabwe stands out as a particularly fast-growing market, with projected annual growth of around 11% in students choosing India as a study destination.

Meanwhile, the Middle East and North Africa region continues to contribute steadily to India’s inbound student population, with students from the United Arab Emirates expected to account for about 5% of India’s international student cohort by 2030.

Policy Reforms Strengthening India’s Appeal

The report attributes much of India’s growing attractiveness to policy initiatives and structural reforms in the higher education sector. Programmes such as Study in India have simplified admission processes and reduced financial barriers for international applicants.

At the same time, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has introduced major changes aimed at internationalisation. These include allowing foreign universities to establish campuses in India and enabling institutions to expand seats for international students. The University Grants Commission now permits universities to reserve up to 25% additional seats for overseas applicants.

India’s long-term ambition is even more ambitious. The country aims to host 500,000 international students by 2047, signalling a strong national commitment to becoming a global education hub.

Indian Students Abroad Diversifying Destinations

Even as India attracts more international students, it continues to remain a major source of global student mobility. More than 800,000 Indian students were studying abroad in 2024, making India the world’s second-largest source of international students.

However, the report suggests that the traditional “Big Four” destinations — the US, UK, Canada, and Australia — may see a slight decline in their share of Indian students, with combined enrolments expected to fall by around 0.5% annually through 2030.

Instead, Indian students are increasingly exploring new destinations such as Germany, France, and the United Arab Emirates, attracted by lower tuition costs and accessible study pathways.

Key Challenges for Indian Universities

Despite the optimistic outlook, the report identifies several challenges that India must address to fully realise its potential as an international education hub.

One major issue is institutional reputation. While Indian universities have improved their employer reputation rankings — with the median score improving by 61 places since 2017 — academic reputation indicators have shown limited progress.

“India has long been central to global student mobility — as both a major sending market and an increasingly influential destination”

Another challenge relates to graduate employability. A Mercer-Mettl report in 2025 found that only 42.6% of Indian graduates are considered employable, highlighting the need for stronger industry connections and work-integrated learning opportunities.

Infrastructure also remains a concern. Rapid expansion of international enrolments without adequate investments in housing, campus facilities, and student support services could undermine the overall student experience.

A Strategic Moment for India

Ashwin Fernandes, Chair QS India and Vice President for Strategic and International Engagement at QS, emphasised that India now stands at a critical moment in global higher education mobility.

“India has long been central to global student mobility — as both a major sending market and an increasingly influential destination. The conditions are shifting in India’s favour, from government policy and affordability to regional demographic pressure. But sustaining this momentum will require institutions to close the gap between reputation and real-world graduate outcomes.”

Scenarios for 2030

The report outlines three possible scenarios for the future of India’s higher education landscape by 2030. These include stronger regional student flows across Asia and Africa, the rise of technology-enabled hybrid learning models, and a global competition among countries to attract international talent.

How India responds to these shifts, the report concludes, will determine whether the country can convert its growing demand advantage into lasting leadership in international education.

Society

The Science Story Behind Middle Eastern Oil

How ancient oceans, microscopic life, and deep geological time turned the Middle East into the world’s energy heartland — and why that matters in the era of the Iran–Israel crisis

How ancient oceans, microscopic life, and deep geological time turned the Middle East into the world’s energy heartland — and why that matters in the era of the Iran–Israel crisis

When geopolitical tensions flare in the Middle East (West Asia), global markets tremble. Oil prices surge, shipping routes become strategic flashpoints, and diplomats rush to prevent wider conflict. The recent escalation involving Iran and Israel has once again drawn attention to the region’s central role in the global energy system.

But the real story of Middle Eastern oil began long before modern politics, long before nation-states, even long before humans existed.

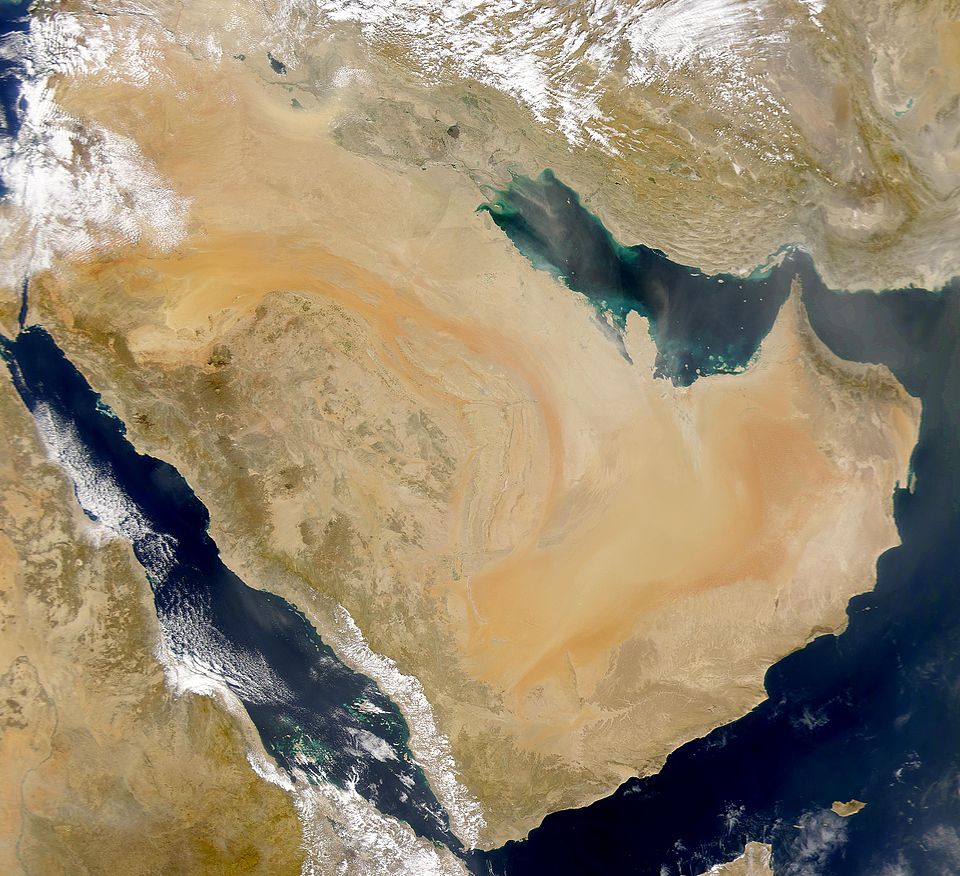

It began hundreds of millions of years ago — in a vast tropical ocean that once covered much of what is now desert.

The immense oil reserves beneath the Middle East are not simply a matter of luck. They are the result of a rare convergence of geological processes that unfolded over hundreds of millions of years. Scientists often describe it as a geological perfect storm: the right organisms, the right environment, the right rocks, and the right tectonic conditions.

Together, they created one of the richest hydrocarbon provinces on Earth.

When the Middle East Was an Ocean

Today the Arabian Peninsula is associated with scorching deserts and arid landscapes. But during several periods in Earth’s distant past — particularly between 300 million and 50 million years ago — much of the region lay beneath warm, shallow seas.

These seas were biologically rich environments filled with microscopic organisms such as plankton, algae, and marine bacteria. When these organisms died, their remains settled on the seafloor, forming thick layers of organic material.

Normally, dead organisms would decompose and disappear. But under certain conditions — particularly when oxygen levels are low — organic material can accumulate faster than it decays.

Over millions of years, these deposits were buried under layers of sediment such as sand, clay, and limestone. As burial continued, pressure and temperature gradually increased.

Under these conditions, the organic matter slowly transformed into hydrocarbons — the molecules that make up crude oil and natural gas.

This transformation process, known as thermal maturation, typically takes tens of millions of years.

By the time the process was complete, the remains of ancient microscopic life had become the petroleum that fuels modern economies.

The Birth of Source Rocks

In petroleum geology, the first critical ingredient for oil formation is what scientists call a source rock — a rock formation rich in organic material capable of generating hydrocarbons.

The Middle East contains some of the most productive source rocks ever discovered.

One famous example is the Jurassic-age source rock systems beneath the Persian Gulf, which produced enormous volumes of petroleum over geological time. Because these source rocks formed in stable marine environments rich in organic matter, they generated hydrocarbons in extraordinary quantities.

Once oil forms inside source rocks, it does not remain there permanently. Oil and gas molecules are lighter than water and tend to migrate upward through porous rock layers.

This migration leads to the next crucial stage in oil accumulation.

The Role of Reservoir Rocks

Oil cannot be extracted directly from source rocks in most cases. Instead, it migrates into reservoir rocks — porous formations that can store hydrocarbons.

Many Middle Eastern oil fields are located in carbonate reservoirs, particularly limestone and dolomite formations. These rocks are ideal storage spaces because they contain microscopic pores and fractures that allow fluids to accumulate and flow.

The Middle East’s geological history produced vast carbonate platforms — essentially enormous underwater limestone systems built by marine organisms such as corals and shell-forming creatures.

These formations eventually became some of the most productive oil reservoirs in the world.

In places like Saudi Arabia, reservoir rocks are so permeable that oil can flow relatively easily compared with many other parts of the world. This is one reason Middle Eastern oil is often cheaper to extract than petroleum from more complex geological settings.

Nature’s Underground Traps

Even if oil forms and migrates into reservoir rocks, it can still escape unless something traps it underground.

In petroleum geology, these traps are essential. Without them, hydrocarbons would eventually leak to the surface.

The Middle East possesses an abundance of these traps. One important mechanism involves evaporite deposits — thick layers of salt and gypsum that formed when ancient seas evaporated. These rocks act as nearly impermeable seals that prevent oil from escaping.

Another type of trap forms through tectonic folding, when geological forces bend rock layers into arches or domes. Oil migrating upward becomes trapped beneath these structures.

Over millions of years, enormous volumes of petroleum accumulated in such formations. The result: giant oil fields that contain billions of barrels of crude oil.

The World’s Largest Oil Fields

Because of this combination of favourable geological factors, the Middle East hosts several of the largest oil fields ever discovered.

Among them is the famous Ghawar Field, located in eastern Saudi Arabia. Discovered in 1948, it remains the largest conventional oil field on Earth.

Stretching over roughly 280 kilometers, Ghawar has produced tens of billions of barrels of oil since operations began.

Other massive fields exist across the region in countries such as Iraq, Kuwait, and United Arab Emirates.

Together, these reserves account for roughly half of the world’s proven oil resources.

Few other regions possess such geological abundance.

Why Oil Is Easier to Extract Here

Another reason the Middle East dominates global oil production lies in the quality and accessibility of its reservoirs.

In many parts of the world — such as shale basins in North America — extracting oil requires advanced techniques like hydraulic fracturing.

But in much of the Middle East, reservoirs are large, pressurized, and geologically simple. In some cases, early wells produced oil that flowed naturally to the surface due to underground pressure.

These favorable conditions have historically made Middle Eastern oil among the least expensive to produce globally.

This economic advantage has shaped global energy markets for decades.

The Geography of Energy

Geology alone does not explain the region’s strategic importance. Geography also plays a critical role.

Much of the oil produced in the Middle East must pass through narrow maritime routes before reaching global markets.

One of the most important of these is the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow waterway connecting the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea.

Roughly one-fifth of the world’s oil supply travels through this corridor.

Tankers carrying petroleum from Gulf states must navigate this passage before heading toward Asia, Europe, and North America.

Because of this, the strait is widely considered one of the most strategically sensitive shipping routes on Earth.

Any disruption there can send shockwaves through global energy markets.

Oil and Modern Geopolitics

The first major oil discovery in the Middle East occurred in 1908 in Iran, marking the beginning of a new era in global energy.

Over the following decades, vast reserves were discovered across the Arabian Peninsula.

These discoveries transformed desert economies into some of the wealthiest states in the world.

They also reshaped international politics.

Oil wealth funded massive infrastructure development, modern cities, and sovereign wealth funds. At the same time, competition over resources contributed to geopolitical rivalries, international alliances, and strategic military interests.

The Middle East gradually became the focal point of global energy security.

Today, developments in the region influence oil markets worldwide.

When tensions rise — as in the current standoff involving Iran and Israel — investors and governments immediately worry about disruptions to energy supply.

A Resource Formed in Deep Time

The story of Middle Eastern oil reminds us that modern geopolitics often rests on geological foundations laid long before human history.

The hydrocarbons that power today’s global economy were created from the remains of microscopic organisms that lived hundreds of millions of years ago.

Ancient seas nurtured these organisms. Sediments buried them. Pressure and heat transformed them into petroleum.

Then geological forces trapped the oil deep underground until modern technology uncovered it.

In this sense, the oil fields of the Middle East are time capsules from Earth’s deep past.

The Future Beyond Oil

Despite the region’s enormous reserves, the world is gradually moving toward alternative energy systems.

Renewable technologies such as solar, wind, and green hydrogen are expanding rapidly. Even many oil-producing countries in the Middle East are investing heavily in energy diversification.

Yet petroleum will likely remain an important part of the global energy mix for decades.

As long as that remains true, the geological legacy of ancient oceans beneath the Middle East will continue to influence global politics.

The tensions between Iran and Israel are shaped by many factors — ideology, security concerns, and regional rivalries. But beneath all these lies another reality: the region sits atop one of the most extraordinary geological endowments on Earth.

A resource formed in deep time continues to shape the present.

And perhaps, for some time yet, the future.

Society

How the Iran–Israel–US Conflict Ripples Through India’s Economy and Energy Future

The immediate reality is uncertainty: higher freight, rising insurance, volatile crude, jittery exporters

The tremors began far from India’s shores. US and Israeli strikes on Iran, followed by retaliatory actions, have redrawn fault lines across West Asia. But in New Delhi, in oil refineries along the western coast, and in rice mandis across Haryana and Punjab, the aftershocks are already being felt.

“US and Israel attacks on Iran, and subsequent counter attacks have exposed a new wave of geopolitical risks,” notes a policy briefing from Climate Trends, reviewed by EdPublica. For India — bound to Israel by strategic ties and to Iran by history and geography — the moment is fraught with complexity.

At the heart of the unfolding crisis lies a narrow maritime artery: the Strait of Hormuz.

The Strait of Hormuz: India’s Energy Lifeline

Nearly a quarter of the world’s crude oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz — a chokepoint linking West Asian producers to global markets. For South Asia, the dependency is sharper. Around 40% of the total crude oil consumption of India, China, Japan and South Korea transits this passage.

India imports nearly 90% of its crude oil. Of its daily imports, 2.5–2.7 million barrels per day — largely from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and the UAE — pass through these contested waters.

The risks are no longer theoretical. According to reports, Iran has been relaying warnings over VHF radio to ships, cautioning that passage may not be guaranteed. Insurance pricing for shipping has risen by 50% overnight. Freight rates are climbing. The Director General of Shipping has issued a circular advising stakeholders not to deploy Indian crews in Iran.

If Iran’s 3.3 million barrels per day production is disrupted, oil prices could rise 9–15%, pushing crude from a base of $70 per barrel to roughly $76–81.

For India, the impact would be “more price driven and not volume driven”. Yet price shocks ripple quickly — widening the current account deficit, weakening the rupee and feeding domestic inflation.

Vivek Y. Kelkar, researcher working at the intersection of geo-economics and sustainability, warns: “Much depends on how long the conflict endures and whether risks to the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz persist… For India, the impact would be indirect but significant. With nearly 90 percent import dependence, every $10 per barrel rise increases the annual import bill by about $13–14 billion, widening the current account deficit, pressuring the rupee and adding to inflation.”

He adds that China — which buys roughly 90% of Iran’s crude exports — could pivot more aggressively toward Russian, Iraqi, Saudi and West African grades if Iranian volumes shrink. “If Beijing pivots toward the same Russian or Atlantic Basin supplies that India relies on for diversification, India’s energy security could become more expensive and more contested. The likely outcome is not deep scarcity, but tighter global balances, higher prices and diminished negotiating leverage for Indian refiners.”

From Oil Tanks to Rice Fields

The consequences extend well beyond petrol pumps.

In the weeks before the conflict escalated, Iranian importers had placed large orders for basmati rice, pushing local prices up by about ₹10 per kg. Iran accounts for roughly 25% of India’s basmati exports; Iraq another 20%. Together, that’s over 2 million tonnes valued at more than $2 billion annually.

Uncertainty now looms over these trade flows. Tea exports too may take a hit — nearly ₹7 billion worth was exported to Iran in 2024–25.

More broadly, Middle Eastern countries including Iran, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE account for bilateral trade worth about $117.32 billion, with the UAE alone contributing nearly $100 billion. Any regional escalation directly threatens these ties.

The UAE Factor: A Stable Hub Under Strain

Dubai has long been viewed as West Asia’s insulated commercial gateway — a financial and logistics hub even when politics elsewhere burned. But the conflict “fundamentally alters Dubai’s longstanding reputation as a politically insulated financial and trade hub”. India and the UAE have been expanding cooperation in renewables, green hydrogen and critical minerals. The India–UAE Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), signed in 2022, marked India’s first such accord in the MENA region. Escalation now risks slowing joint ventures and technology exchanges just as clean transition investments were gathering pace.

“India’s policy of strategic autonomy has so far helped it navigate the choppy waters of geopolitics but the balancing act has become increasingly tough. The conflict in west Asia and its repercussions raise the risks to its supply chains, test energy security and increase insurance costs and fuel inflation if energy prices remain elevated, as is expected if the Strait of Hormuz is blocked… Yet, despite the rising risks India’s economy and markets are relatively better placed to ride this geopolitical storm,” Archana Chaudhary, Associate Director at Climate Trends, notes.

A Clean Energy Imperative, Not Just a Climate Goal

The crisis may also sharpen India’s clean energy calculus. Elevated oil costs increase dollar demand, typically putting downward pressure on the rupee. Costlier fuel filters into transportation, logistics and eventually food prices. Renewable energy supply chains — including critical minerals — could also be disrupted, as significant shipping traffic flows through Hormuz

Yet analysts see opportunity in the turbulence. “The recent strikes only reinforce the validity of India’s long-standing principle of strategic autonomy. In an increasingly volatile West Asian landscape, the wisdom of accelerating our clean energy ambitions becomes even more apparent for energy security. Reducing dependence on imported conventional energy sources, i.e. oil and gas, through rapid deployment of clean technologies is no longer just a climate imperative but a strategic necessity… In this fractured geopolitical order, India must deepen the momentum toward clean energy transition and technological self-reliance to insulate its growth trajectory from external shocks,” Aarti Khosla, Director, Climate Trends, argues.

Vaibhav Chaturvedi, Senior Fellow at CEEW, echoes the urgency: “The US-Iran war doesn’t bode well for the global energy economy. In the short run, we can expect an increase in oil prices. In the medium term, if the war drags, there would be a negative impact on the global economy. The event will undoubtedly create headwinds for India’s economy. India will do well to leverage its relationships to access cheaper oil in this scenario. This is a moment to bring investments to ramp up plans to scale up electrification of the power and transport sector faster as the ultimate solution to energy security.”

Duttatreya Das, Energy Analyst–Asia at Ember, calls this a turning point: “The past few months have been challenging for India’s crude supplies—first the shift away from discounted Russian Urals to avoid U.S. tariffs, and now the potential volume impact from disruptions in West Asia. While these disruptions may be short-term, India cannot simply afford to remain hostage to geopolitical volatility… Moments like these offer an opportunity to recalibrate its mobility policy, through electrification and a faster expansion of ethanol blending in the near term.”

A Moment of Strategic Testing

In South Block, a Cabinet meeting chaired by the Prime Minister signals the seriousness of the moment. OPEC has indicated it may adjust production to maintain market stability. India’s long-held doctrine of strategic autonomy — balancing relationships across rival blocs — is now under stress. After US pressure restricted purchases of Russian oil, India diversified more toward Gulf suppliers, inadvertently deepening its exposure to Hormuz-linked risks. Though it imports from over 40 countries, geography and geopolitics cannot be entirely diversified away.

The immediate reality is uncertainty: higher freight, rising insurance, volatile crude, jittery exporters.

The longer-term question is whether this crisis accelerates a structural pivot. In the shadows of tankers and warships, India’s energy transition debate is no longer abstract. It is entangled with inflation, trade, currency stability and food security.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

Society3 months ago

Society3 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet