Earth

A Region on the Edge: Ocean Heat, Island Peril, and a Global Wake-up Call

Real-world impacts in the South-West Pacific — from disappearing glaciers to cultural erosion in Fiji — illustrate what is at stake.

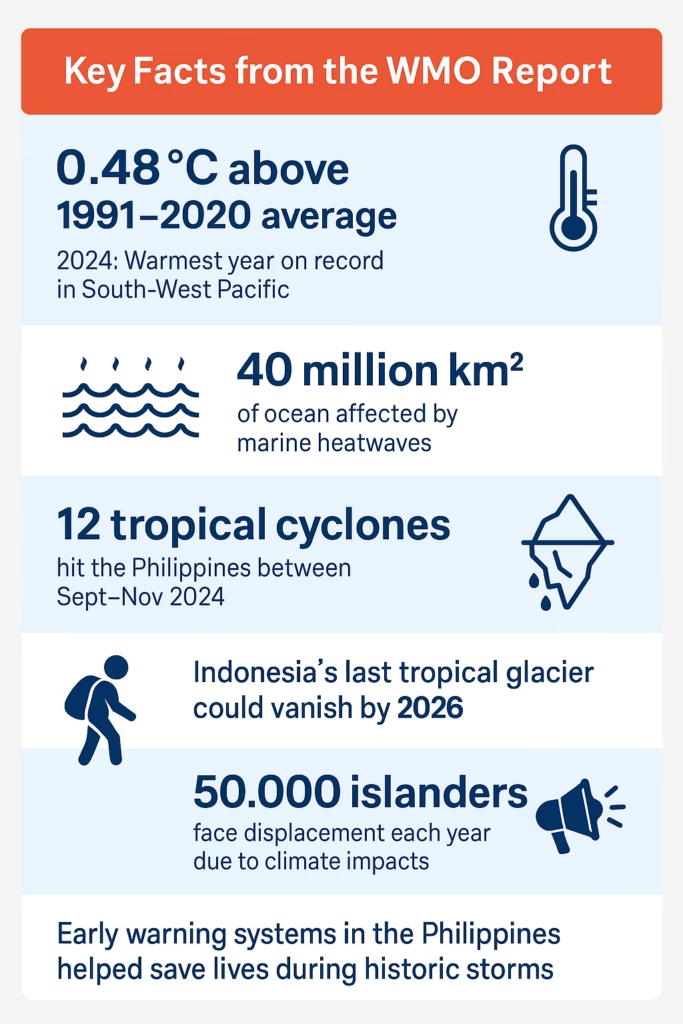

In a stark warning for the world, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) released its latest report in June first week, The State of the Climate in the South-West Pacific 2024, painting a vivid picture of escalating climate extremes across ocean and land. The report, released to coincide with the 2025 Global Platform on Disaster Risk Reduction in Geneva and ahead of the 2025 UN Ocean Conference, warns that the South-West Pacific is already grappling with the climate future the rest of the world fears.

A record-breaking Year

2024 marked the warmest year on record for the region, driven by El Niño conditions and unprecedented ocean heating. Nearly 40 million square kilometers — over 10% of the global ocean surface — was scorched by marine heatwaves.

“2024 was the warmest year on record in the South-West Pacific region. Ocean heat and acidification combined to inflict long-lasting damage to marine ecosystems and economies. Sea-level rise is an existential threat to entire island nations. It is increasingly evident that we are fast running out of time to turn the tide,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Celeste Saulo in a recent media statement.

The heat was not limited to oceans. Extreme temperatures shattered records in Australia and the Philippines, increasing health risks and straining already vulnerable infrastructure.

Storms, floods, and vanishing ice

The report recounts an unprecedented cyclone season in the Philippines: 12 storms in just three months, affecting over 13 million people and displacing 1.4 million. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s last tropical glacier in New Guinea may vanish by 2026. Satellite estimates show a 30-50% ice loss since 2022.

Precipitation patterns swung to extremes. While Malaysia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea faced above-average rainfall and floods, parts of Australia and New Zealand were parched by drought.

The ocean in crisis

The annual sea surface temperature in 2024 was the highest since records began in the early 1980s. Combined with acidification and deoxygenation, ocean warming is devastating marine life and altering storm patterns.

Worryingly, the South-West Pacific sea-level rise already exceeds the global average, threatening islands where over half the population lives within 500 meters of the coast.

Displacement and cultural loss

The Fijian island of Serua, battered by floods and eroding shores, exemplifies the dire choices communities must make.

Despite government offers to relocate, many residents resist because of their deep connection to the land, or “vanua,” a concept embedding identity, spirituality, and ancestry.

“On two separate occasions, the island experienced such extreme flooding that it was possible to cross the entire island by boat without encountering land,” the WMO report said.

Hope in anticipation: Early warnings save lives

Not all is bleak. A case study from the Philippines showcased how early warning systems and anticipatory action helped mitigate the toll of the 2024 cyclone season. The Food and Agriculture Organization’s anticipatory action teams helped relocate fishing boats and distribute cash aid ahead of the storms.

“While the frequency of tropical cyclones may decrease, their intensity will rise. Building resilience is essential,” the report warns.

A Global Response: UNOC3 Signals Change, But Action Must Follow

As the WMO’s warnings echoed, the United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC3) concluded in Nice, France (June 9-13, 2025), providing a parallel platform of hope and accountability.

- The High Seas Treaty reached 49 ratifications, nearing the 60 needed for enforcement.

- Nearly $10 billion in funding was pledged for ocean health, though experts note that the real need is $175 billion annually.

- Countries endorsed the 30×30 conservation goal and backed measures against deep-sea mining and plastic pollution.

“We must move from plunder to protection,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres in his closing address.

These developments reinforce the urgency of the WMO findings. Real-world impacts in the South-West Pacific — from disappearing glaciers to cultural erosion in Fiji — illustrate what is at stake.

The South-West Pacific is not a distant front line. It is the epicenter of an unfolding climate reality. With international mechanisms like the High Seas Treaty nearing activation and early warning systems proving effective, the question is no longer whether we can respond — but whether we will act in time.

As the seas rise and the clock ticks, it’s not just islands at risk. It’s the future of global climate stability.

Earth

EP Investigation: Hidden Epidemic, Tuberculosis Spreads Among Kerala’s Captive Elephants

An EP Investigation into tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants reveals human transmission risks, weak screening systems, and urgent policy gaps.

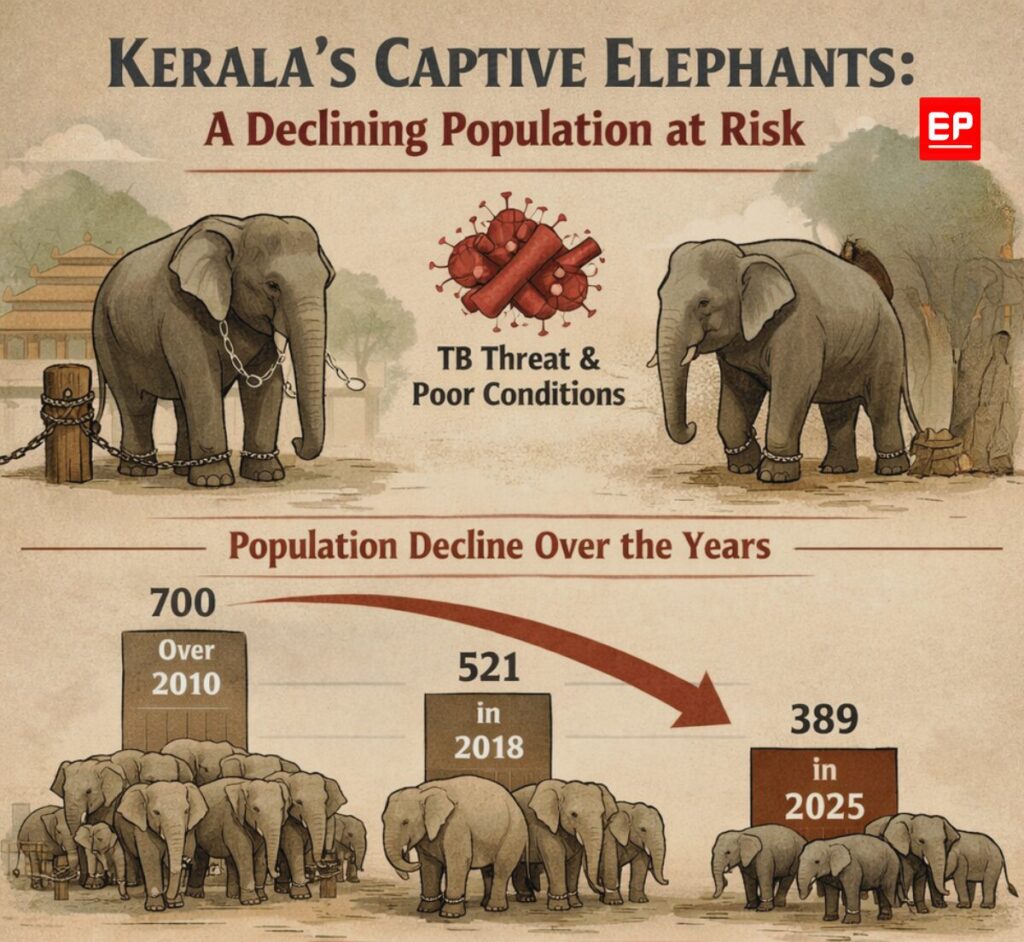

Tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants has become a silent but persistent threat, driven largely by human-to-animal transmission, chronic stress, and systemic failures in veterinary public health. An EdPublica (EP) Investigation reveals how the absence of routine screening, weak governance, and prolonged neglect could turn a preventable disease into a far larger crisis in the years ahead.

By Lakshmi Narayanan | EP Investigation

Tuberculosis is quietly spreading among Kerala’s captive elephants, sustained not by wildlife exposure but by human contact, chronic stress, and systemic neglect. Long treated as a marginal veterinary issue, the disease represents a serious and largely ignored public health and animal welfare crisis—one that experts warn could intensify in the coming years if left unaddressed.

Kerala hosts one of the largest populations of captive Asian elephants in India, housed by temples, private owners, and festival organisers. According to a Forest Department survey concluded in February 2025, the state currently has 389 captive elephants, marking a steady decline from 521 in 2018 and over 700 in 2010, with the majority now owned by private individuals. This sharp reduction over the past decade reflects broader stresses within the captive elephant system, including ageing animals, declining ownership viability, and chronic health concerns.

Within this shrinking population, tuberculosis is neither new nor rare; it is endemic. Historical veterinary records and animal welfare documentation indicate that in earlier years, TB may have contributed to as many as 25 captive elephant deaths annually. Yet in recent times, detailed and transparent reporting on TB-related infections and fatalities has largely disappeared from public view, creating a misleading impression that the risk has diminished when, in reality, surveillance itself has weakened.

This absence of attention does not signal reduced risk. Tuberculosis is a slow, insidious disease that can remain latent or undiagnosed for years. Without mandatory screening or transparent surveillance, infection can circulate undetected within captive elephant populations—allowing animals to suffer prolonged illness and potentially function as silent reservoirs of infection.

The persistence of tuberculosis among captive elephants is not accidental. It is the result of a convergence of vulnerabilities: constant exposure to infected humans, immune suppression driven by captivity-related stress, and systemic failures in veterinary public health governance. Together, these factors have created ideal conditions for a preventable disease to endure—largely unseen, and largely unchallenged.

The Human–Elephant Interface: A Critical Transmission Pathway

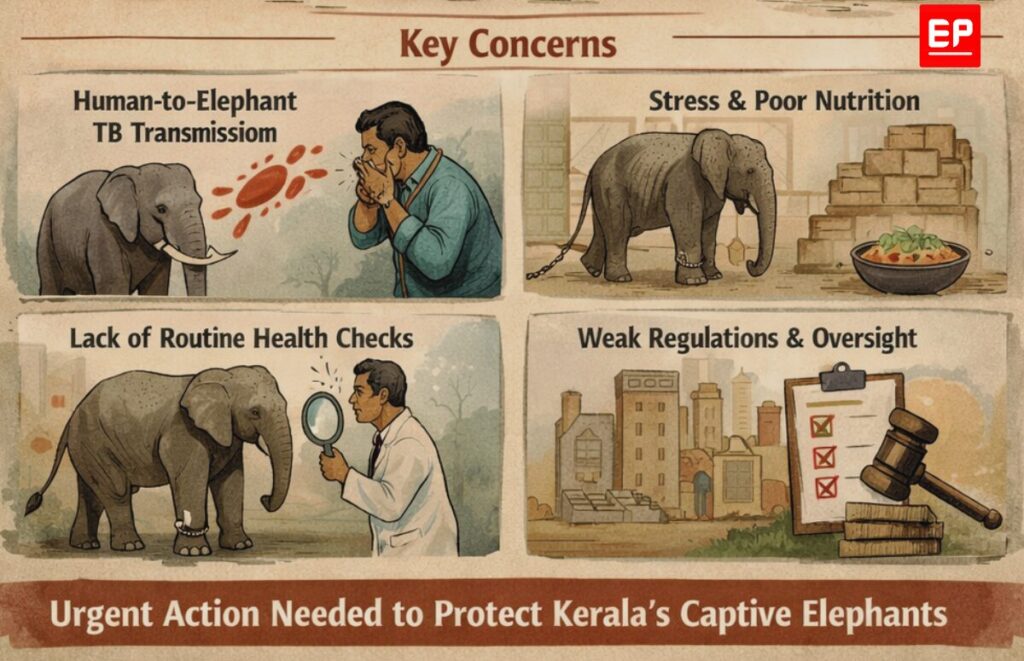

The primary route of TB transmission among Kerala’s captive elephants is reverse zoonosis: the spread of infection from humans to animals. The causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a human-adapted pathogen transmitted through respiratory aerosols. In settings where elephants live and work in close proximity to people, this pathway becomes epidemiologically decisive.

Mahouts and handlers represent the most significant source of chronic exposure. Their daily routines—feeding, bathing, training, and transporting elephants—require prolonged, close physical contact. If a handler carries an active or latent TB infection, the opportunity for transmission to the animal is constant and cumulative.

In addition to handlers, the general public constitutes a secondary but important exposure source. Kerala’s festival culture routinely places elephants amid dense crowds, often for extended periods. These gatherings create intermittent but high-volume opportunities for transmission from undiagnosed or untreated individuals within the broader population. Together, these human reservoirs ensure that captive elephants are rarely insulated from the pathogen. Yet exposure alone does not fully explain disease persistence. The risk of infection is significantly magnified by conditions that undermine the elephants’ immune defenses.

“Tuberculosis in captive elephants is a severe and often underestimated disease. What is seen during post-mortem examinations is extensive, chronic organ damage that reflects prolonged suffering rather than sudden illness. These findings are consistent with long-term exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and delayed detection, Dr. Arun Vishvanathan, a veterinary expert based in Kerala’s Palakkad district, tells EdPublica.

“From a medical and public health perspective, this condition is particularly concerning because it is largely driven by human-to-animal transmission. Elephants living in close, continuous contact with people—especially under stressful captive conditions—experience immune suppression, which allows the infection to progress unchecked. This is not an unavoidable disease; it is a preventable one. Without routine screening of both handlers and elephants, early diagnosis, and strict biosecurity measures, such cases will continue to occur, resulting in needless animal suffering and ongoing public health risk,” Dr. Arun Vishvanathan adds.

Stress, Captivity, and Immune Compromise

Captive environments impose profound physiological and psychological stress on elephants, a species evolved for expansive movement, complex social structures, and environmental autonomy. Confinement to restricted spaces, prolonged chaining, limited exercise, and forced participation in noisy, crowded festivals all contribute to chronic stress.

Scientific evidence across species demonstrates that sustained stress suppresses immune function. In elephants, this immunosuppression reduces resistance to opportunistic infections such as TB and increases the likelihood that latent infections will progress to active disease.

Crowding further compounds the problem. Elephants housed in close quarters or transported frequently between venues are exposed not only to more humans but also to environments conducive to airborne disease transmission. In these conditions, respiratory pathogens can spread efficiently, especially when animals are already physiologically compromised.

”Tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants spreads primarily through close, repeated contact with infected humans, and is sustained by conditions that weaken the animals’ natural defenses. Unlike many wildlife diseases, this is not an infection originating in forests—it is largely a human-driven disease cycle. Mahouts and handlers are the most significant transmission source. Daily activities such as feeding, bathing, chaining, and transport require close physical proximity, often for hours at a time. If a handler has active or undiagnosed TB, the elephant is repeatedly exposed to infectious aerosols,” says Manuprasad, an elephant welfare worker from Thrissur.

Festival crowds and tourists create additional exposure. During temple festivals and public events, elephants are surrounded by dense crowds, sometimes for entire days. In these settings, even brief exposure to multiple infected individuals can result in infection.

Systemic Gaps in Veterinary Public Health

Perhaps the most critical vulnerability lies not in biology but in governance. Kerala lacks a standardized, mandatory TB screening programme for captive elephants. As a result, infected animals—many of them asymptomatic—remain undiagnosed for years. This failure in routine surveillance effectively blinds any meaningful public health response and allows elephants to function as silent reservoirs of infection.

Experts warn that tuberculosis in Kerala’s captive elephants could expand if mandatory screening and biosecurity measures are not urgently implemented.

Nutritional inadequacy is another systemic issue. Economic pressures within the temple and festival ecosystem often translate into suboptimal feeding regimes. Poor nutrition weakens immune responses, lowering the infectious dose required for TB to establish and spread.

Compounding these challenges is a widespread lack of awareness among elephant owners and handlers regarding TB transmission and prevention. Clear, enforceable biosecurity protocols—covering quarantine, treatment, and movement restrictions for TB-positive animals—are largely absent or inconsistently applied. Without such measures, even identified cases pose an ongoing risk to other elephants and to humans.

”As an animal rights and welfare activist, I have personally witnessed the post-mortem of an elephant affected by tuberculosis, and it was deeply distressing. The extent of internal damage revealed the severe and prolonged suffering this animal endured—far beyond what most people realize. Seeing such devastation in an animal of immense strength and dignity is heartbreaking,” explains Ambili Purackal, founder of DAYA, a Kerala-based NGO known for its proactive role in the state’s animal rights movement.

What makes this suffering even harder to accept is that it is largely the result of human exposure. Elephants do not face tuberculosis at these levels in the wild; they contract it through forced, prolonged contact with humans under stressful captive conditions that weaken their immunity. This is not just a veterinary concern but a moral one. These elephants are silent victims of preventable disease, and their suffering is a consequence of human neglect and systemic failure,” Ambili Purackal says.

Secondary and Less-Documented Risks

While human-to-elephant transmission remains the dominant concern, other pathways cannot be entirely dismissed. Interactions with domestic livestock or wildlife in shared environments may contribute to transmission chains, though this remains poorly documented in the Indian context. These ancillary risks further underscore the need for comprehensive epidemiological research.

A Convergence of Vulnerabilities

Taken together, the vulnerabilities facing Kerala’s captive elephants form a self-reinforcing cycle. Constant exposure to a human TB reservoir, chronic immune compromise driven by captivity-related stress and poor nutrition, and systemic failures in disease detection and control create ideal conditions for TB persistence.

Breaking this cycle will require a multi-layered public health approach—one that integrates routine screening, improved nutrition, handler health monitoring, and enforceable management protocols. Without such intervention, tuberculosis will remain a silent epidemic, exacting a slow but devastating toll on one of Kerala’s most culturally significant animal populations.

Silence, in this case, is not neutrality—it is risk.

What Needs to Change

Addressing tuberculosis among Kerala’s captive elephants requires coordinated action across animal welfare, public health, and governance. Experts and welfare workers interviewed by EdPublica point to the following urgent priorities:

1. Mandatory TB Screening

· Routine, standardised tuberculosis testing for all captive elephants

· Regular TB screening for mahouts, handlers, and caretakers

· Immediate isolation and treatment protocols for positive cases

2. Handler Health Monitoring

· Integration of mahout health checks into public TB control programmes

· Confidential diagnosis and treatment access to reduce stigma and underreporting

3. Improved Living Conditions

· Reduced chaining and confinement

· Adequate daily exercise and social interaction

· Limits on festival exposure, crowd density, and noise-related stress

4. Nutritional Standards

· Enforced minimum nutrition guidelines

· Regular veterinary audits to ensure immune-supportive diets

5. Biosecurity and Movement Controls

· Quarantine protocols for newly acquired or transferred elephants

· Restrictions on inter-district or inter-state movement of TB-positive animals

6. Transparent Reporting and Oversight

· Publicly accessible data on TB cases and outcomes

· Independent audits of temple and private elephant management practices

7. Interdepartmental Coordination

· Formal collaboration between forest, animal husbandry, and public health departments

· Recognition of TB in captive elephants as a One Health issue—linking human, animal, and environmental health

Some sources in this investigation have requested anonymity due to professional or personal safety concerns. Their identities are known to EdPublica and their statements have been independently verified.

Earth

Life may have learned to breathe oxygen hundreds of millions of years earlier than thought

Early life on Earth has found an interetsing turning point. A new study by researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggests that some of Earth’s earliest life forms may have evolved the ability to use oxygen hundreds of millions of years before it became a permanent part of the planet’s atmosphere.

Oxygen is essential to most life on Earth today, but it was not always abundant. Scientists have long believed that oxygen only became a stable component of the atmosphere around 2.3 billion years ago, during a turning point known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). The new findings indicate that biological use of oxygen may have begun much earlier, potentially reshaping scientists’ understanding of how life evolved on Earth.

The study, published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, traces the evolutionary origins of a key enzyme that allows organisms to use oxygen for aerobic respiration. This enzyme is present in most oxygen-breathing life forms today, from bacteria to humans.

Scientists have long believed that oxygen only became a stable component of the atmosphere around 2.3 billion years ago, during a turning point known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). The new findings indicate that biological use of oxygen may have begun much earlier, potentially reshaping scientists’ understanding of how life evolved on Earth

MIT geobiologists found that the enzyme likely evolved during the Mesoarchean era, between 3.2 and 2.8 billion years ago—several hundred million years before the Great Oxidation Event.

The findings may help answer a long-standing mystery in Earth’s history: why it took so long for oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere. Scientists know that cyanobacteria, the first organisms capable of producing oxygen through photosynthesis, emerged around 2.9 billion years ago. Yet atmospheric oxygen levels remained low for hundreds of millions of years after their appearance.

While geochemical reactions with rocks were previously thought to be the main reason oxygen failed to build up early on, the MIT study suggests biology itself may also have played a role. Early organisms that evolved the oxygen-using enzyme may have consumed small amounts of oxygen as soon as it was produced, limiting how much could accumulate in the atmosphere.

“This does dramatically change the story of aerobic respiration,” said Fatima Husain, postdoctoral researcher in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, said in a media statement. “Our study adds to this very recently emerging story that life may have used oxygen much earlier than previously thought. It shows us how incredibly innovative life is at all periods in Earth’s history.”

The research team analysed thousands of genetic sequences of heme-copper oxygen reductases—enzymes essential for aerobic respiration—across a wide range of modern organisms. By mapping these sequences onto an evolutionary tree and anchoring them with fossil and geological evidence, the researchers were able to estimate when the enzyme first emerged.

“The puzzle pieces are fitting together and really underscore how life was able to diversify and live in this new, oxygenated world

Tracing the enzyme back through time, the team concluded that oxygen use likely appeared soon after cyanobacteria began producing oxygen. Organisms living close to these microbes may have rapidly consumed the oxygen they released, delaying its escape into the atmosphere.

“Considered all together, MIT research has filled in the gaps in our knowledge of how Earth’s oxygenation proceeded,” Husain said. “The puzzle pieces are fitting together and really underscore how life was able to diversify and live in this new, oxygenated world.”

The study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that life on Earth adapted to oxygen far earlier than previously believed, offering new insights into how biological innovation shaped the planet’s atmosphere and the evolution of complex life.

Earth

The Heat Trap: How Climate Change Is Pushing Extreme Weather Into New Parts of the World

MIT scientists say a hidden feature of the atmosphere is allowing dangerous humid heat to build up in parts of the world that were once considered climatically mild — setting the stage for longer heat waves and more violent storms.

For decades, long spells of suffocating heat followed by explosive thunderstorms were largely confined to the tropics. But that pattern is now spreading into the planet’s midlatitudes, and researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology believe they know why.

In a new study published in Science Advances, MIT scientists have identified atmospheric inversions — layers of warm air sitting over cooler air near the ground — as a critical factor controlling how hot, humid, and storm-prone a region can become. Their findings suggest that parts of the United States and East Asia could face unfamiliar and dangerous combinations of oppressive heat and extreme rainfall as the climate continues to warm.

Inversions are already notorious for trapping air pollution close to the ground. The MIT team now shows they also act like thermal lids, allowing heat and moisture to accumulate near the surface for days at a time. The longer an inversion persists, the more unbearable the humid heat becomes. And when that lid finally breaks, the stored energy can be released violently, fuelling intense thunderstorms and heavy downpours.

“Our analysis shows that the eastern and midwestern regions of U.S. and the eastern Asian regions may be new hotspots for humid heat in the future climate,” said Funing Li, a postdoctoral researcher in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, in a media statement.

The mechanism is especially important in midlatitude regions, where inversions are common. In the US, areas east of the Rocky Mountains frequently experience warm air aloft flowing over cooler surface air — a configuration that can linger and intensify under climate change.

“As the climate warms, theoretically the atmosphere will be able to hold more moisture,” said Talia Tamarin-Brodsky, an assistant professor at MIT and co-author of the study, in a media statement. “Which is why new regions in the midlatitudes could experience moist heat waves that will cause stress that they weren’t used to before.”

Why heat doesn’t always break

Under normal conditions, rising surface temperatures trigger convection: warm air rises, cool air sinks, clouds form, and storms develop that can eventually cool things down. But the researchers approached the problem differently, asking what actually limits how much heat and moisture can build up before convection begins.

By analysing the total energy of air near the surface — combining both dry heat and moisture — they found that inversions dramatically raise that limit. When warm air caps cooler air below, surface air must accumulate far more energy before it can rise through the barrier. The stronger and more stable the inversion, the more extreme the heat and humidity must become.

“This increasing inversion has two effects: more severe humid heat waves, and less frequent but more extreme convective storms,” Tamarin-Brodsky said.

A Midwest warning sign

Inversions can form overnight, when the ground cools rapidly, or when cool marine air slides under warmer air inland. But in the central United States, geography plays a key role.

“The Great Plains and the Midwest have had many inversions historically due to the Rocky Mountains,” Li said in a media statement. “The mountains act as an efficient elevated heat source, and westerly winds carry this relatively warm air downstream into the central and midwestern U.S., where it can help create a persistent temperature inversion that caps colder air near the surface.”

As global warming strengthens and stabilises these atmospheric layers, the researchers warn that regions like the Midwest may be pushed toward climate extremes once associated with far warmer parts of the world.

“In a future climate for the Midwest, they may experience both more severe thunderstorms and more extreme humid heat waves,” Tamarin-Brodsky said in a media statement. “Our theory gives an understanding of the limit for humid heat and severe convection for these communities that will be future heat wave and thunderstorm hotspots.”

The study offers climate scientists a new way to assess regional risk — and a stark reminder that climate change is not just intensifying known hazards, but exporting them to places unprepared for their consequences.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet