Interviews

‘Democratise Sanskrit, it’s the time for third Sanskrit revolution’

Sanskrit is the best weapon to wipe out the remnants of colonisation in Indian minds, says author and Sanskrit scholar Oscar Pujol

Oscar Pujol dedicated a lifetime to introducing the Sanskrit language to Spain and the world. He came to India in the 1970s to follow his love and found his destiny and birth purpose in Kashi (Varanasi), the much-celebrated spiritual destination in India’s Uttar Pradesh state. Oscar Pujol is a Spanish-Sanskrit scholar and author who came from Spain, the land of bullfighting, flamingo dancing, and football, and immersed himself in the cultural diversity of India as if it were a mission.

He studied Sanskrit at the Banaras Hindu University and published several books and translations from the Sanskrit classics and the two Sanskrit dictionaries: the Sanskrit-Catalan and the Sanskrit-Spanish. In 2002, he helped establish Casa Asia in Barcelona. He founded the Instituto Cervantes in New Delhi in 2007. He recently received the ‘Vani Foundation Distinguished Translator Award’ at the Jaipur Literature Festival for establishing a closer relationship between Sanskrit and Spanish languages through his works. He has previously held the post of director at the Cervantes Institute of New Delhi and Rio de Janeiro and was the director of Educational Programmes at Casa Asia. The books authored by Pujol include the first dictionary of Sanskrit to Catalan, a dictionary of Sanskrit to Spanish, and a book on the eminent Indian saint Shankaracharya’s philosophy and scriptures in Spanish. His latest translation of the Indian spiritual text Bhagavad Gita from Sanskrit to Spanish has been released under the name ‘La Bhagavad Gita’. In an interview with Dipin Damodharan, he speaks on several issues, ranging from the relevance of Sanskrit to the third Sanskrit revolution.

As for the common people, Sanskrit is still not a popular language. What is the reason to think that Sanskrit is still relevant?

Sanskrit is still relevant for many reasons. Not just for spiritual reasons. Sanskrit is the philosophy of science. It is the language of energy and vision. It is the language of medicine, astronomy, and astrology. It is the language of logic, politics, and morality. It is the language of Kamasastra (refers to the tradition of works on Kāma: Desire). Ultimately, it is the language of salvation.

There is no other country that knows the essence of the human spirit as India. The reason for that is Sanskrit. It is Sanskrit that made India the world leader. I believe that India is still a world leader, and I believe it will be the same in the future. Deviation from the Sanskrit tradition led to the downfall of India. But now many good things are happening. Many of the younger generations show interest in Sanskrit. Apart from India, this is evident in many countries, like the US and Mauritius.

Efforts should be made to protect the traditional scholars (Pandits) who consider Sanskrit their lifeblood. Only through them will this tradition continue. The government should provide more benefits to keep Sanskrit alive.

Sanskrit was the language that defined India. But why did Sanskrit lose its importance?

It happened for historical and political reasons. Sanskrit lost its political power. It is a big story. But remember that history has ups and downs. Let us not forget our heritage while embracing modernity. Unfortunate. That was what happened in the last 60–70 years. Do not be put off yet. The climate in the country is now for Sanskrit to regain its political power. Things need to be done to save the soul of India.

The third revolution should be to make Sanskrit global. It has to start from India itself; no one else can be the flag bearer of the third revolution

There is an argument often raised by critics of Sanskrit and Indian philosophies—that it is misogynistic and non-inclusive. How do you look at this?

Leave the accusations on their way. Here exists the vision of worshipping knowledge. It is beyond mere thought. ‘Inclusiveness’ is fundamentally a part of India’s philosophy. The problem came when they tried to imitate the West as an end. Eternal visions are beyond all colours. Everything is based on karma (actions).

Is learning Sanskrit difficult for common people?

Never. If I, who claim no Indian heritage, can do it, you all can easily. Central and federal governments can come up with various schemes to facilitate Sanskrit learning. If you want to understand the philosophies of India without confusion, I suggest learning Sanskrit. All translations and interpretations in other languages have their limitations. Don’t fall for the western thinking that so-called science is the pinnacle of knowledge. Meanwhile, don’t celebrate false pretensions based on Sanskrit itself. Western countries see the world as human-centred. But India’s visions are centred on life. That is what makes India the best country to lead the world. The power that makes India a world leader is never military. Rather, it is knowledge. Sanskrit is the best weapon to wipe out the remnants of colonisation in Indian minds.

Sanskrit changed the intellectual outlook of Europe to a great extent. The influence of Sanskrit on European languages laid the foundation for the Renaissance movements there

You have written about the necessity of a third Sanskrit revolution. Can you elaborate on the background of the three Sanskrit revolutions?

The first Sanskrit revolution took place in the Middle Ages. The time when the rays of Indian knowledge reached the West through Muslim scholars. That’s how it came to Spain. It was transmitted to the West through the Al-Andalus period. That is how systems like the decimal system were introduced to the world.

Sanskrit changed the intellectual outlook of Europe to a great extent. The influence of Sanskrit on European languages laid the foundation for the Renaissance movements there. The second revolution began when Western scholars began to study Sanskrit in the 19th century. It revolutionised language learning in Europe. Phonetics itself is a contribution of Sanskrit.

The third revolution should be to make Sanskrit global. It has to start from India itself; no one else can be the flag bearer of the third revolution.

Is it being said that the democratisation of Sanskrit is the necessity of this era? What can be done about it?

Of course. What we need is to democratise Sanskrit. That is the third Sanskrit revolution that India should lead, as mentioned earlier. The process of making Sanskrit a ‘universal language’ should take place. The government has to spend more money for that. Now there is a tendency to see individuals as superior and progressive if they speak English. Those who know Sanskrit are left out. That has to change. The first step to democratising Sanskrit is to make it easier to learn.

In order to popularise Sanskrit, these five things should be focused activities. One is to protect traditional Sanskrit scholars. They are becoming extinct. Second, the ‘narrative’ that Sanskrit is an outdated way of life must be rewritten. Sanskrit has the most liberal ideas and open-minded visions. To be modern, you must wipe out the remnants of colonisation in your mind with Sanskrit as your weapon.

Third, take policy decisions to create an environment where Sanskrit is accessible to all. Fourth, develop a strong global network involving foreign scholars. It is happening today, albeit on a smaller scale, from Japan to Argentina and from the US to Russia. Five, transform Sanskrit like yoga, and globalise it; now yoga is universal. Make it the language of the world.

Interviews

Geometry, Curiosity and Finding ‘Her’ Place

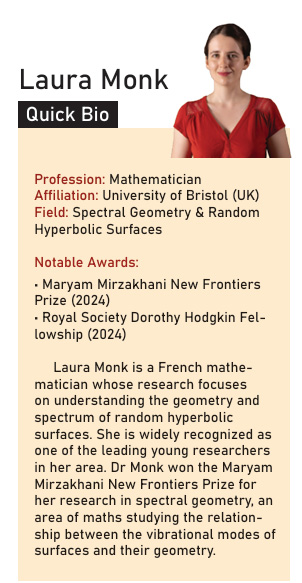

Dr Laura Monk has quickly become one of the field’s most exciting young geometers

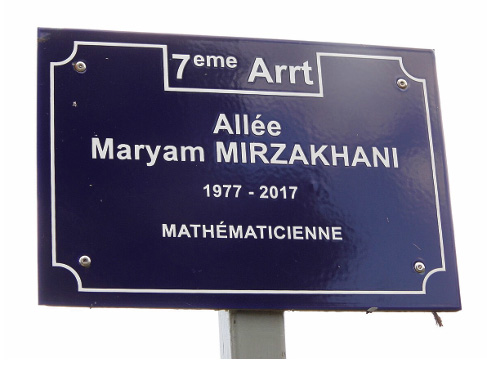

In modern mathematics, where imagination meets deep abstraction, Dr Laura Monk has quickly become one of the field’s most exciting young geometers. In 2024, she was awarded the Maryam Mirzakhani New Frontiers Prize, an honour regarded as one of the most prestigious recognitions for early-career women mathematicians and presented at the Breakthrough Prize ceremony—often called the “Oscars of Science.” A mathematician whose work explores the geometry of negatively curved spaces, Monk’s path into the field was shaped not only by intellectual fascination but also by uncertainty, self-doubt, and the search for belonging—a journey familiar to many women in STEM. Growing up in France, she found early encouragement from teachers who pushed her to think harder and explore deeper. Later, mentors like Nalini Anantharaman and the pioneering legacy of Iranian math genius Maryam Mirzakhani helped her see that mathematics could be a creative, expansive world—not an exclusive club.

A Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow and Lecturer at the University of Bristol, Monk works on the geometry of negatively curved spaces and the behaviour of objects moving within them. In this conversation with Dipin Damodharan, she speaks candidly about intuition, representation, hyperbolic geometry, and the courage required to stay in mathematics when you’re not sure you fit.

‘Go for it! Math is super cool and useful’

To start with, could you tell us how your journey in mathematics began? Was there a defining moment when you realised this would become your life’s work?

I always enjoyed mathematics at school and thought it would be a good idea to study it, as I was interested in it and it opens the door to many jobs. After my first two years of study, I realized I loved the subject itself more than the idea of finding a job using it, and decided I wanted to work in mathematics (probably as a teacher).

I faced many challenges and doubts—I somehow never felt sure mathematics was “for me,” even though I loved it. But I’m very happy I stuck with it and made a few leaps of faith at the right times. At the end of my master’s, I decided to start a PhD because it is required for certain higher education teaching positions in France. I thought: three years is a lot of time, better get excited and really go for it! Luckily, I met my PhD advisor, Nalini Anantharaman, who introduced me to a fascinating research project.

The way she ventured into different areas of mathematics, tackling ambitious new projects with no apparent fear, was an incredible inspiration. She was very different from the image I had of “the mathematician.” Her mentorship made me feel confident I could do it if I wanted to. And then I did!

Growing up in France, were there specific teachers, mentors, or institutions that played a pivotal role in shaping your mathematical thinking?

Mathematics is taught and shared, and I have many teachers to thank for my mathematical upbringing. My high-school teacher had extremely high standards and told me off a few times for doing the minimum instead of pushing myself. My second-year teacher gave me a first glimpse of how exciting venturing into the unknown can be during a research project.

One of the ways maths is taught in France is through a two-year intensive preparatory school followed by further studies at university. I found this structure gave me a strong basis to build on, as well as methods to organize myself and work well.

What were some of the challenges you faced as a young woman entering a field often dominated by men? How did you navigate them?

Mathematics is, indeed, a very masculine field, and one could imagine sexist behaviours to be common. I have to say, luckily perhaps, that this has not been my experience. I have always felt extremely welcomed into this community, whether as a student or a researcher.

However, I did still struggle very much as a student with finding a sense of place and purpose in what I was doing. Though these difficulties are quite universal, I think they were amplified by being one of the only girls in my cohort. Identifying this was very helpful in overcoming these feelings, because it led me to build strong connections with my peers, to find female mentors and role models, and to invest myself in events for young women, all of which helped tremendously.

Much of your work lies at the intersection of geometry and dynamics. Could you explain your research focus in simple terms?

I study certain types of surfaces called “hyperbolic surfaces.” Unlike a piece of paper (which is flat) or a sphere (which is positively curved), hyperbolic surfaces have negative curvature: they look like Pringles. There exist many, many hyperbolic surfaces, and they appear in very different fields of mathematics: number theory, mathematical physics, dynamics…

I am trying to understand what these surfaces “look like” a bit better. In order to do so, I put all of them in a (big) bag, take one at random, and try to describe it.

Mathematics often requires deep abstraction. How do you stay connected to the beauty or “reality” behind these abstractions?

I relate more to the beauty than the reality! To me, mathematics is a gigantic world that we are building or exploring together. I find a lot of joy in how different parts of this world interact and how bridges can be built; simple ideas can come together from far apart and create something new.

What role does intuition play in your mathematical process?

A big role! One of the reasons why I have been drawn to mathematics is that, once you understand a formula or a theorem, you don’t really need to memorize it by heart anymore: it just makes sense. When I learn something new, I go through a lengthy process of unravelling everything and I often feel very confused (or sometimes even a bit desperate!).

But, one day, all of a sudden, everything becomes clear, to the extent that it is even hard to remember why I was so lost initially. I think this is one of the reasons why it is so hard for us to share and convey what we do to one another, or to the general public.

Maryam Mirzakhani’s groundbreaking work in geometry and moduli spaces continues to inspire mathematicians globally. In what ways has her work influenced your own research? You have worked on topics that build upon or are inspired by Mirzakhani’s legacy. Could you speak about this continuity—how do you see her influence evolving in your field?

Maryam Mirzakhani created my research field, and I have studied a certain part of her work in great detail. My research consists in picking a hyperbolic surface at random and looking at it. She was one of the first people to have had this amazing idea. At the time, there existed a probability model allowing one to pick hyperbolic surfaces at random, but it was completely abstract and unusable.

Through several beautiful breakthroughs, she created a method that made this possible. We are still at the beginning of the wide variety of applications following from these advances.

If you could give a message to a young girl fascinated by numbers but unsure about pursuing math, what would you say?

Go for it! Math is super cool and useful, so you will have loads of fun and learn a lot. It is ok if you don’t identify with the image of the “math guy”; there are a lot of ways to enjoy math. It is not just about proving theorems or solving exercises, it is about creativity and sharing.

Outside of mathematics, what brings you joy or fuels your curiosity?

I quite like jigsaw puzzles and knitting, both of which relax me and make me appreciate how a lot of little steps can come together to create something big. Right now, my main source of joy is my two-year-old daughter, and seeing her discover the world. If only we could stay this curious and observant about every single little thing!

Do you think artificial intelligence and computers are changing the way we do mathematics?

Computers definitely have! We used to pay people to perform long lists of computations for researchers, and to publish entire books of randomly generated numbers in order to study probabilities. Now both of these activities seem very silly. Mathematicians use computers all the time, whether to perform experiments, find the answer to a simple question, or write and share their work.

I personally choose to be optimistic about the future of AI. You would have a very hard time conveying to someone in 1980 the role that computers play in everyone’s lives, but for mathematics, they have greatly enlarged our experience and allowed us to go faster, further. Things are scary now because we do not know what is ahead of us.

Interviews

Dr. Saji Kumar Sreedharan’s Quest to Restore Memory in Aging and Disease

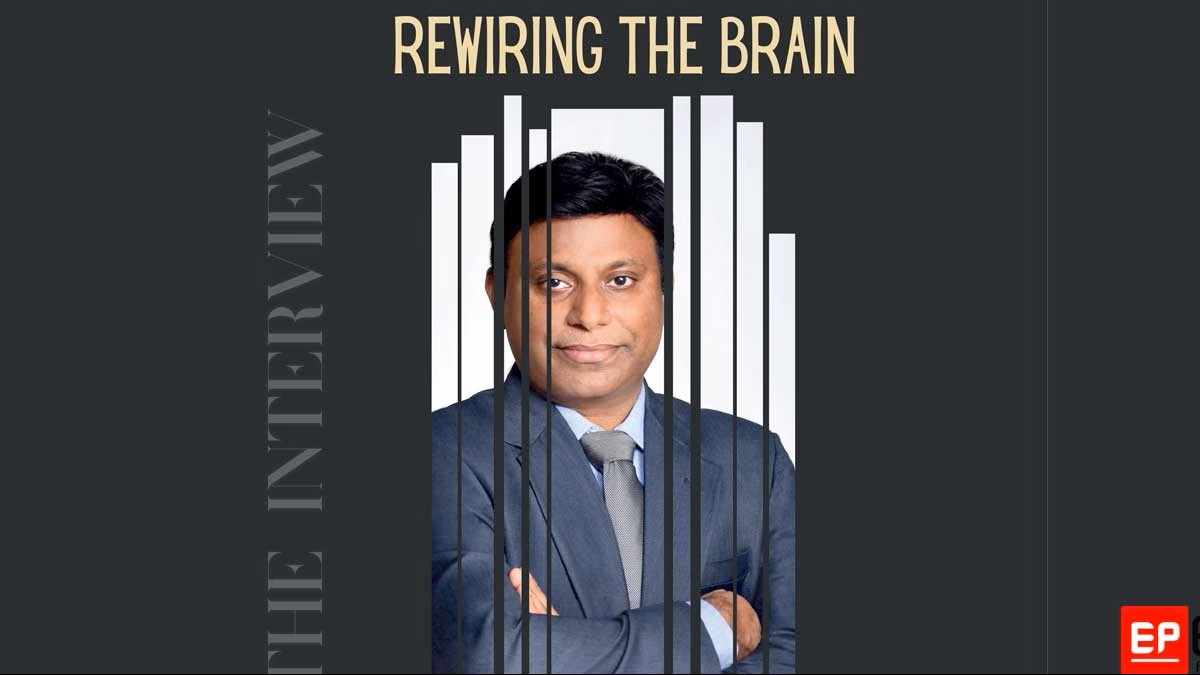

Dr. Saji Kumar Sreedharan’s work has significantly contributed to our understanding of long-term memory storage, the neural basis of memory, and the impact of aging on memory function

Dr. Saji Kumar Sreedharan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Physiology at the National University of Singapore, where he leads research focused on healthy aging and neurodegeneration. His work has significantly contributed to our understanding of long-term memory storage, the neural basis of memory, and the impact of aging on memory function. A pioneer in exploring the molecular and cellular mechanisms behind memory processes, Dr. Sreedharan’s research utilizes advanced tools like optogenetics and chemogenetics to manipulate and study neural networks. He is particularly interested in finding ways to “rewire” or restore the neural networks to preserve memory function in conditions like Alzheimer’s and mental health disorders.

In an interview with EdPublica’s Dipin Damodharan, Dr. Saji Kumar Sreedharan shares insights into his journey into neuroscience, the challenges and breakthroughs in memory research, and his vision for the future of the field. Meet the man unraveling the mysteries of memory: excerpts from Dr. Saji Kumar Sreedharan’s exploration of the brain’s secrets.

Q: Can you tell us about your journey into the field of neuroscience? What initially sparked your interest in memory research?

I was born and raised in a small village called Chingoli in Alappuzha, near Haripad in Kerala, India. My home was close to a lake, and from a young age, I observed the seasonal changes that happened there. The lake is brackish, meaning saltwater and freshwater exchange every six months. With these changes came noticeable shifts in the plants and animals around the lake. I used to document these changes out of curiosity.

One particular observation was the abundance of a reptile, the skink (arana in local language), in our area. My mother would often warn me to be cautious around skinks, saying that if one bit you, death was certain. At the same time, she also mentioned that skinks never actually bite because they forget their intention within a few seconds. This curious idea sparked my interest, and I asked her why skinks forget everything so quickly. She explained it was due to how their brain is designed and told me that, when I grew up, I could learn more about how the brain stores memories.

Her words stayed with me, and I began reading many books on the brain and memory. This was my first spark of inspiration, and it eventually led me into the field of neuroscience.

Q: Over the past two decades, what specific experiences or challenges have shaped your research focus on long-term memory storage?

The world is advancing rapidly, thanks to scientific discoveries. These breakthroughs are possible because of the incredible abilities of our brains, where our neural networks fuel imagination and creativity. Neuroscience, in particular, is a field that uses new techniques to explore the basic workings of memory.

In the past two decades, methods like optogenetics and chemogenetics have given neuroscientists powerful tools to study memory. Optogenetics is a technique where scientists use light to turn specific brain cells on or off, which normally wouldn’t respond to light. Chemogenetics, on the other hand, allows scientists to activate or deactivate neurons by adding specific chemicals.

These techniques bring both challenges and opportunities. Now, we can target and control specific areas of the brain. For example, imagine a person with psychological issues receiving optogenetic or chemogenetic stimulation in specific brain regions to help manage their emotions and behavior—this could be incredibly useful. While this is currently being tested in animal models, I hope that, in the near future, it could be used to help humans as well.

Q: Your research has been recognized for significantly advancing our understanding of memory formation. Could you elaborate on your key findings related to the transition from short-term to long-term memory?

I have been working in the field of learning and memory since 2000. My first mentor in neuroscience was Prof. T. Ramakrishna, the founder and first head of the Life Sciences Department at the University of Calicut, India. He was a great motivator, and we often had insightful discussions about learning and memory in the evenings. I had the chance to work with him for my master’s dissertation, which was my first real research experience. Prof. Ramakrishna encouraged me to expand my knowledge further, and he connected me with Dr. Shobi Valeri, a senior researcher in Delhi at the time.

Dr. Shobi soon left for Germany to pursue his Ph.D. and recommended me to DRDO (Defence Research and Development Organisation). Dr. Shobi is now a senior scientist at the National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad. I worked at DRDO for a year before moving to Magdeburg, Germany, where I began my Ph.D. under Prof. Juletta Frey. She is well-known in the field of learning and memory, particularly for her research on the cellular mechanisms involved in forming associative memory.

In Prof. Frey’s lab, I discovered how different pieces of information can link together to form long-term memories. This work later inspired the development of many computational models of memory. After completing my Ph.D., I did my postdoctoral studies with Prof. Martin Korte in Braunschweig. There, I discovered how activating neurons before learning could enhance memory formation in the future, a process known as metaplasticity—an exciting and emerging area of neuroscience.

Since 2012, I have been working at the National University of Singapore, where I have focused more on aging, neurodegeneration, and mental health. Using animal models, we have uncovered the role of specific brain regions, like CA2 and CA1, in forming social and spatial memories—both of which are significantly affected by aging, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental health conditions.

Q: How do you approach the study of molecular mechanisms in memory, and what methodologies do you find most effective?

In my lab, we approach research questions by looking at them from different angles—molecular, cellular, behavioural, and system-level. We choose the most appropriate method depending on the specific question we’re investigating. I can’t say that one method is better than the others because each plays an important role in confirming our findings.

Recently, we’ve been using optogenetic and chemogenetic tools, which allow us to target and stimulate specific neurons. These methods are particularly helpful because they ensure precision in how we activate or deactivate brain cells.

Q: Congratulations on receiving the “Investigator” award from the International Association for the Study of Neurons and Brain Diseases. What does this recognition mean to you personally and professionally?

Thank you for your kind words. As a researcher, I feel proud and happy that my work is being recognized internationally. Professionally, this recognition is a big motivation to continue pursuing my research.

This achievement is not just mine alone—I owe it to all my Ph.D. students, postdocs, and research technicians who have worked with me over the past 20 years. This award is for them as well.

Q: How do you feel your work contributes to the broader scientific community, especially concerning memory impairments related to aging and mental health?

I am the Research Director of the Healthy Longevity Translational Research Programme at the School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, where we have more than 36 scientists working on various aspects of healthy aging. One of our key areas is brain health. Living a long life is not meaningful without a healthy brain.

I am one of the principal investigators studying how neural networks are impaired during aging and neurodegeneration. My wife, Dr. Sheeja Navakkode, is also a neuroscientist, focusing on Alzheimer’s disease using animal models. Neural networks undergo tremendous changes during aging and in various mental health conditions. Our goal is to correct or rewire neural network activity so that memory can be preserved with minimal damage, especially during conditions such as aging, Alzheimer’s Disease, and mental health disorders.

Q: Looking ahead, what are some of the new directions or questions in memory research that you are excited to explore?

Looking ahead, I’m excited to explore several new directions in memory research. One of the key areas of interest is how neural networks in the brain change during aging and neurodegenerative diseases. I’m particularly interested in finding ways to “rewire” or restore these networks to preserve memory function in conditions like Alzheimer’s and mental health disorders. Additionally, using advanced tools like optogenetics and chemogenetics, we can now target specific brain regions with precision, opening up possibilities to understand how different areas of the brain contribute to memory formation and retrieval.

Q: How do you envision the future of memory research, particularly in relation to technology and treatment for memory-related disorders?

I envision the future of memory research as being heavily influenced by advancements in technology, particularly through tools like optogenetics and chemogenetics. These methods allow us to precisely target and manipulate specific neural networks, which could lead to breakthroughs in understanding and treating memory-related disorders like Alzheimer’s. As we continue to explore how neural networks change with aging and neurodegeneration, we can potentially develop targeted therapies to restore or enhance memory function, offering hope for effective treatments in the future.

Q: What advice would you give to young researchers who aspire to make significant contributions to the field of neuroscience?

My advice to young researchers is to find a mentor who inspires you and helps nurture your curiosity. A good mentor can shape your scientific journey in ways you might not even realize. Focus on being self-motivated, enthusiastic, and hardworking—these qualities matter more than grades or academic achievements. Science requires passion, not just effort. If you’re truly curious and dedicated, you won’t waste time complaining; you’ll immerse yourself in the work. Always approach your research with the mindset of a lifelong learner, and remember, science is not just a job—it’s a passion that drives discovery and innovation.

Q: Finally, how do you balance the demands of research, teaching, and mentorship in your role as an Associate Professor?

Balancing the demands of research, teaching, and mentorship as an Associate Professor requires careful prioritization and passion for each role. In research, I stay focused on exciting new directions in memory studies and neurodegeneration while managing a team of talented scientists. In teaching, I aim to inspire students by sharing my enthusiasm for neuroscience and guiding them through complex concepts. Mentorship is one of the most fulfilling aspects of my career, where I focus on nurturing curiosity and passion in my students, helping them grow both personally and professionally. Ultimately, I approach all three areas with the mindset of a lifelong learner, driven by a deep love for science and a commitment to making a meaningful impact.

The Sciences

Memory Formation Unveiled: An Interview with Sajikumar Sreedharan

“Our goal is to correct or rewire neural network activity so that memory can be preserved with minimal damage, especially during conditions such as aging, Alzheimer’s Disease, and mental health disorders.”

In an enlightening conversation with EdPublica, Sajikumar Sreedharan, Associate Professor at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Singapore, shares his research insights on memory formation and the transition from short-term to long-term memory. His areas of research include aging and neurodegeneration, the neural basis of long-term memory (LTM), and synaptic tagging and capture (STC) as an elementary mechanism for storing LTM in neural networks. He also explores metaplasticity as a compensatory mechanism for improving memory in neural networks. With a career spanning over two decades, Prof. Sreedharan discusses his key findings, innovative methodologies, and the significance of receiving the “Investigator” award from the International Association for the Study of Neurons and Brain Diseases. Join us as he reflects on his journey and the collaborative spirit that drives his research.

Edited Excerpts:

Your research has been recognized for significantly advancing our understanding of memory formation. Could you elaborate on your key findings related to the transition from short-term to long-term memory?

I have been working in the field of learning and memory since 2000. My first mentor in neuroscience was Prof. T. Ramakrishna, the founder and first head of the Life Sciences Department at the University of Calicut, Kerala, India. He was a great motivator, and we often had insightful discussions about learning and memory in the evenings. I had the chance to work with him for my master’s dissertation, which was my first real research experience. Prof. Ramakrishna encouraged me to expand my knowledge further, and he connected me with Dr. Shobi Valeri, a senior researcher in Delhi at the time.

Dr. Shobi soon left for Germany to pursue his Ph.D. and recommended me to DRDO (Defence Research and Development Organisation). Dr. Shobi is now a senior scientist at the National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad. I worked at DRDO for a year before moving to Magdeburg, Germany, where I began my Ph.D. under Prof. Juletta Frey. She is well-known in the field of learning and memory, particularly for her research on the cellular mechanisms involved in forming associative memory.

In Prof. Frey’s lab, I discovered how different pieces of information can link together to form long-term memories. This work later inspired the development of many computational models of memory. After completing my Ph.D., I did my postdoctoral studies with Prof. Martin Korte in Braunschweig. There, I discovered how activating neurons before learning could enhance memory formation in the future, a process known as metaplasticity—an exciting and emerging area of neuroscience.

“Using animal models, we have uncovered the role of specific brain regions, like CA2 and CA1, in forming social and spatial memories—both of which are significantly affected by aging, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental health conditions

Since 2012, I have been working at the National University of Singapore, where I have focused more on aging, neurodegeneration, and mental health. Using animal models, we have uncovered the role of specific brain regions, like CA2 and CA1, in forming social and spatial memories—both of which are significantly affected by aging, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental health conditions.

How do you approach the study of molecular mechanisms in memory, and what methodologies do you find most effective?

In my lab, we approach research questions by examining them from different angles—molecular, cellular, behavioural, and system-level. We choose the most appropriate method depending on the specific question we’re investigating. I can’t say that one method is better than the others because each plays an important role in confirming our findings.

Recently, we’ve been using optogenetic and chemogenetic tools, which allow us to target and stimulate specific neurons. These methods are particularly helpful because they ensure precision in how we activate or deactivate brain cells.

Congrats on receiving the “Investigator” award from the International Association for the Study of Neurons and Brain Diseases. What does this recognition mean to you personally and professionally?

Thank you for your kind words. As a researcher, I feel proud and happy that my work is being recognized internationally. Professionally, this recognition is a significant motivation to continue pursuing my research.

This achievement is not just mine alone—I owe it to all my Ph.D. students, postdocs, and research technicians who have worked with me over the past 20 years. This award is for them as well.

How do you feel your work contributes to the broader scientific community, especially concerning memory impairments related to aging and mental health?

I am the Research Director of the Healthy Longevity Translational Research Programme at the School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, where we have more than 36 scientists working on various aspects of healthy aging. One of our key areas is brain health. Living a long life is not meaningful without a healthy brain.

I am one of the principal investigators studying how neural networks are impaired during aging and neurodegeneration. My wife, Dr. Sheeja Navakkode, is also a neuroscientist, focusing on Alzheimer’s disease using animal models. Neural networks undergo tremendous changes during aging and in various mental health conditions. Our goal is to correct or rewire neural network activity so that memory can be preserved with minimal damage, especially during conditions such as aging, Alzheimer’s Disease, and mental health disorders.

(Read the full interview in the upcoming December 2024 issue of EdPublica magazine.)

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet