EDUNEWS & VIEWS

Indian kids use different math skills at work vs. school

The research, which involved over 200 children, compared the performances of children engaged in market work with those focused solely on their studies

A recent study conducted in Delhi sheds light on the contrasting mathematical abilities of children who work in markets versus those who attend school, raising questions about how educational systems can better address these disparities. The research, which involved over 200 children, compared the performances of children engaged in market work with those focused solely on their studies.

In the study, children were tasked with solving math problems under various conditions. Remarkably, 85 percent of children with market jobs were able to answer a complex market transaction problem correctly, while only 10 percent of their school-going counterparts succeeded in solving a similar question. However, when the same group was given simple division and subtraction problems, with pencil and paper for assistance, the results shifted. Fifty-nine percent of school kids solved the problems correctly, while only 45 percent of market-working children did.

The researchers also introduced a word problem involving a boy buying vegetables at the market. One-third of market-working children successfully solved the problem without any aid, whereas fewer than 1 percent of schoolchildren were able to do the same. This stark difference in performance highlights the potential benefits that practical, real-world experience in the marketplace can offer.

Why, then, do nonworking students seem to struggle more under market conditions?

“They learned an algorithm but didn’t understand it,” said researcher Abhijit Banerjee, explaining the phenomenon. On the other hand, market-working children appeared to have developed useful strategies for managing transactions. One notable example was their use of rounding to simplify calculations. For instance, when faced with multiplying 43 by 11, many market kids would round 43 to 40, multiply by 10, and then add 43 to get the correct result of 473—an intuitive trick that seemed to help them tackle problems more efficiently.

“The market kids are able to exploit base 10, so they do better on base 10 problems,” said Esther Duflo, co-author of the study. “The school kids have no idea. It makes no difference to them.” Conversely, the schoolchildren demonstrated a better understanding of formal written methods for division and subtraction.

The findings raise an important issue: while market-working children excel in solving real-world problems quickly, they may be missing out on the formal education necessary for long-term academic success. “It would likely be better for the long-term futures if they also did well in school and wound up with a high school degree or better,” Banerjee said.

The divide between the intuitive problem-solving skills of market kids and the formal methods taught in school suggests that a new approach could be beneficial in the classroom. Banerjee suspects that traditional teaching methods, which often prioritize a single, formal approach to solving problems, may be limiting. He advocates for encouraging students to reason their way toward an approximation of the correct answer, a method that aligns more closely with the informal strategies used by market-working children.

Despite these concerns, Duflo emphasized, “We don’t want to blame the teachers. It’s not their fault. They are given a strict curriculum to follow, and strict methods to follow.”

The question remains: how can schools adjust their teaching methods to better support students’ diverse problem-solving strategies? The research team is actively exploring new experiments to address this issue, with the goal of creating a more inclusive and effective educational system.

“These findings highlight the importance of educational curricula that bridge the gap between intuitive and formal mathematics,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab’s Post-Primary Education Initiative, the Foundation Blaise Pascal, and the AXA Research Fund.

EDUNEWS & VIEWS

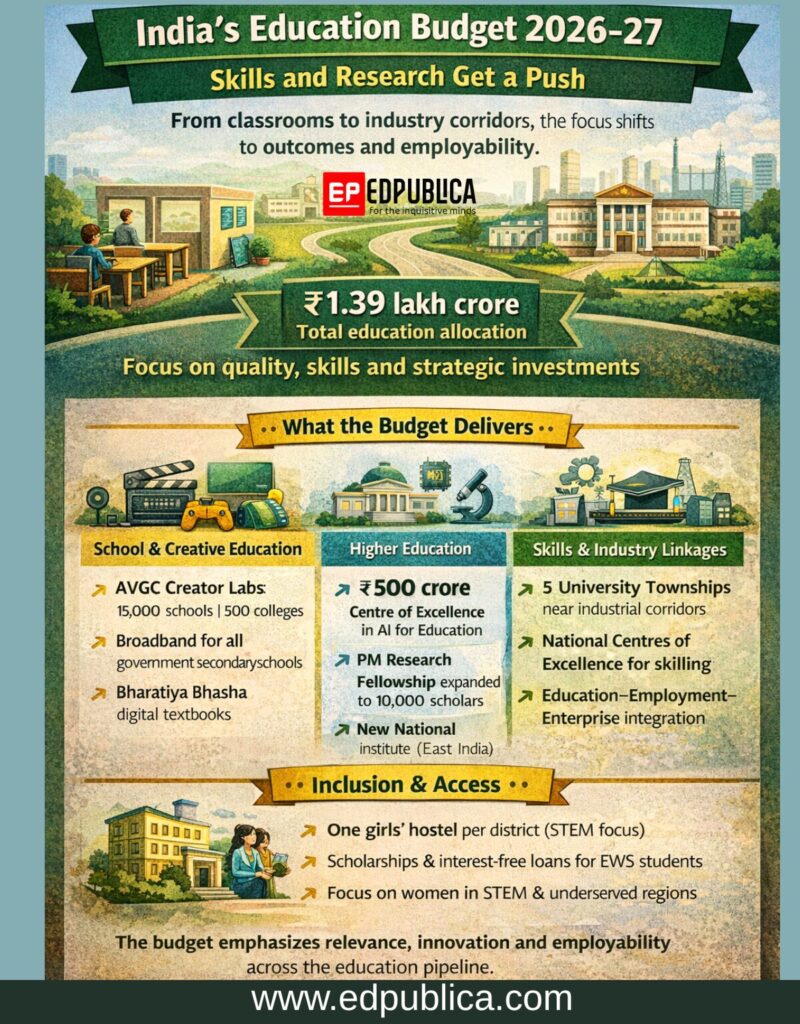

From Classrooms to Corridors: How India’s Budget Repositions Education

Budget 2026–27 reframes education as economic infrastructure—linking skills, research and industry—while shifting India’s learning system away from rote pathways towards future-ready ecosystems.

India’s Union Budget 2026–27 does not dramatically expand headline spending on education, but it signals a clear shift in how education is expected to deliver economic value. With a total allocation of Rs1.39 lakh crore—largely in line with last year—the focus moves decisively from enrolment expansion to outcomes, skills, and integration with industry and research ecosystems.

Presented alongside the government’s Viksit Bharat 2047 (Developed India) vision, the education budget positions learning as a strategic economic investment—one that links schools, universities, skilling centres and enterprises into a single pipeline aimed at employability, innovation and global competitiveness.

From Classrooms to Creative Economies

A major thrust of the budget is the expansion of creative and technology-driven learning. The proposal to establish AVGC (Animation, Visual Effects, Gaming and Comics) Content Creator Labs in 15,000 secondary schools and 500 colleges marks a significant bet on India’s “orange economy,” projected to require nearly two million professionals by 2030.

This creative push is complemented by the announcement of a new National Institute of Design in eastern India and expanded digital infrastructure, including mandatory broadband connectivity for all government secondary schools. Together, these measures signal a move away from textbook-centric learning towards experiential, project-based education aligned with emerging industries.

Dr Bushra, Associate Professor – Finance at JIMS Rohini, describes this as a long-overdue alignment between education and the real economy. “The Union Budget’s strong push to strengthen the education, employment, and enterprise continuum is a progressive step,” she notes, adding that University Townships near industrial and logistics corridors can “significantly enhance experiential education by integrating academia with real-world business ecosystems.”

University Townships and the Industry-Education Bridge

Perhaps the most structural reform in the budget is the proposal to establish five University Townships near major industrial corridors, developed in partnership with states. These townships are envisioned as integrated hubs combining universities, research institutions, skilling centres and industry partners—breaking the long-standing silos between education and employment.

This model reflects a broader policy shift: instead of producing graduates first and searching for jobs later, education is being spatially and institutionally embedded within production and innovation ecosystems.

For higher education institutions, this presents both opportunity and pressure. As Dr Bushra points out, institutions now have a chance to “deepen partnerships with industry, embed emerging technologies such as AI and analytics into curricula, and foster entrepreneurial thinking among students.” At the same time, the success of these townships will depend on execution, governance clarity and sustained state-level engagement.

AI, Research and the End of Rote Learning

The budget’s Rs 500 crore allocation for a Centre of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence for education reinforces the pivot towards research-led, technology-enabled learning. The centre is expected to support AI-driven teaching tools, personalised learning and adaptive assessments across school and higher education.

Atishay Jain, Managing Partner at Koncept Global Books, sees this as a clear departure from legacy learning models. “The Budget’s clear emphasis on research-led education and future technologies like AI signals a shift from rote learning to innovation-driven skill development,” he says. According to Jain, structured investments in advanced learning ecosystems encourage institutions to prepare students for emerging industries rather than “legacy roles.”

This emphasis is reinforced through the expansion of the PM Research Fellowship to 10,000 scholars, new national centres of excellence for skilling, and a stronger focus on translational research that connects academic output with industry application.

Equity, Access and Gender Inclusion

Alongside innovation, the budget also addresses access and equity—albeit selectively. The announcement of one girls’ hostel per district, particularly in STEM-focused institutions, is aimed at improving participation and retention of women in higher education. Scholarships, interest-free loans for economically weaker sections, and continued support for early childhood programmes such as Poshan 2.0 signal continuity in inclusion-focused policy.

“These measures ensure that education remains both aspirational and equitable,” says Dr Bushra, adding that inclusive access must remain central as curricula and delivery models evolve.

What the Budget Still Leaves Open

Despite its forward-looking design, the education budget leaves some structural questions unanswered. Public education spending still falls short of the long-articulated 6 percent of GDP target. Faculty shortages, research commercialisation challenges, and uneven state-level capacity remain persistent bottlenecks.

Moreover, while digital infrastructure and AI integration are emphasised, large-scale teacher upskilling and institutional readiness will determine whether these investments translate into improved learning outcomes rather than isolated pilots.

A Directional Budget for a Knowledge Economy

Union Budget 2026–27 may not be an expansionary education budget, but it is a directional one. By tying education more closely to industry, research and future technologies, it reflects an understanding that India’s demographic dividend can only be realised through relevance, quality and adaptability.

As Atishay Jain notes, strengthening the research and learning foundation will be “critical to nurturing future-ready talent and supporting India’s ambition of becoming a global knowledge powerhouse.” The real test, as with many education reforms, will lie not in intent but in execution—across classrooms, campuses and corridors of industry alike.

Society

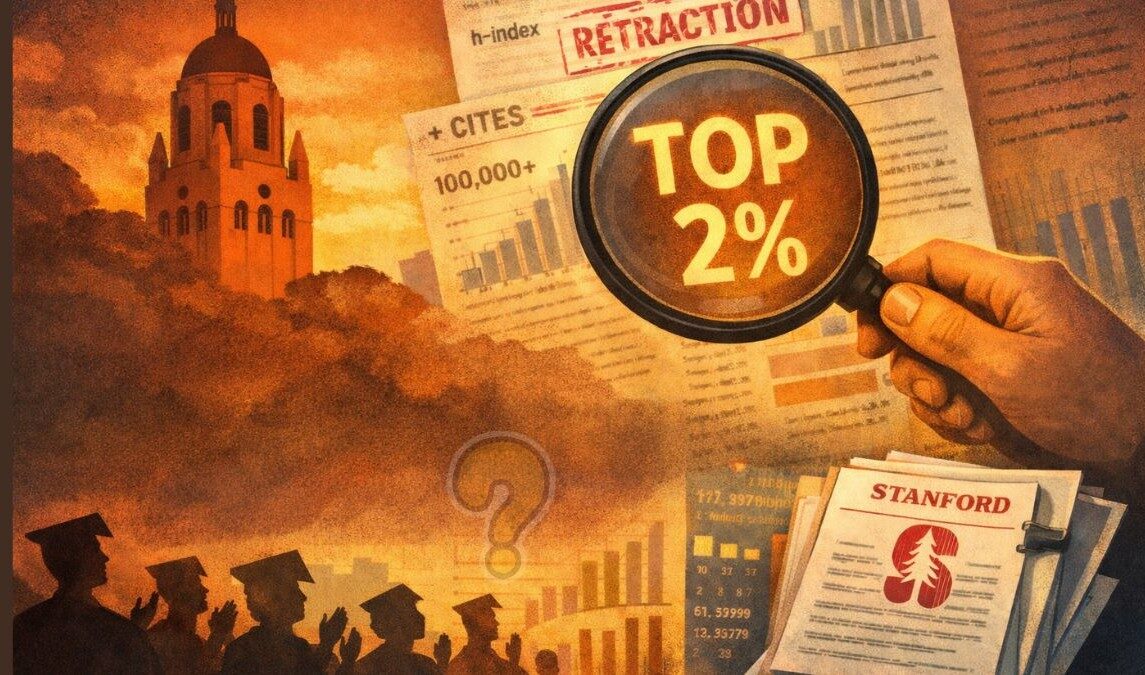

Why the ‘Stanford Top 2% Scientists’ Label Is Widely Misrepresented

What began as a bibliometric dataset has quietly transformed into a badge of prestige across Indian academia…

Last month, a friend sent me a social media card celebrating a science researcher she knows personally. The card was crisp, congratulatory, and emphatic: the researcher had been included in the “Top 2% Stanford Scientists” list. My friend went a step further. In a lecture soon after, she cited the inclusion as proof that the researcher had made it to a prestigious list of Stanford University—a global stamp of academic excellence.

There was no doubt about the researcher’s merit. She is a solid scientist, respected in her field. But the framing stayed with me. Over the next few weeks, I began noticing similar announcements everywhere—university press releases, institutional websites, LinkedIn posts, WhatsApp forwards. The pattern was strikingly uniform: “Our faculty member named in Stanford University’s Top 2% Scientists list.” The implication was clear. Stanford had selected. Stanford had ranked. Stanford had endorsed.

But had it?

That question, according to Achal Agrawal of India Research Watch, is precisely where Indian media reporting has fallen short. “There is no official confirmation that Stanford University endorses this list,” he said while speaking at a recent science conference conducted by SJAI in Ahmedabad, India. “Yet the list is routinely presented as a Stanford ranking, without even basic verification.”

What the List Actually Is

The list commonly referred to as the “Stanford list of top 2% scientists” is based on a large-scale citation analysis developed by a group of researchers led by Professor John P. A. Ioannidis, who is affiliated with Stanford University. It draws on data from Scopus, Elsevier’s citation database, and ranks researchers using a composite bibliometric indicator that combines citations, h-index, co-authorship patterns, and related metrics.

Importantly, this is not an award, nor a peer-reviewed selection process. It is an algorithmic dataset. According to standardized science-wide citation databases created by Ioannidis and collaborators at Stanford, the “Top 2%” list compiles researchers based on composite citation metrics from Scopus — identifying highly cited authors within each field — but it is not a ceremonial award or formal Stanford ranking.

Crucially—and almost never mentioned in celebratory coverage—the dataset itself carries explicit caveats. “The list itself says that it should not be used for evaluation,” Experts pointed out. “That warning is written in the methodology section of the paper.”

What Is Rarely Reported

One of the most striking omissions in media coverage is that the dataset includes a separate column for retractions.

“There is an explicit column for retractions,” Agrawal noted. “There are people in the list with over 100 retractions. In some cases, nearly half of the people being celebrated by universities have retracted papers.”

Despite this, universities across India have published newspaper advertisements highlighting how many faculty members they have in the “top 2% list,” without acknowledging the list’s internal flags or limitations.

This selective storytelling, Agrawal argued, reflects a broader failure of journalistic scrutiny. “It is the media’s duty to question,” he said. “Instead, we have seen hundreds of articles simply reproducing the claim.”

How the Narrative Spreads

The pattern repeats itself across regions. Headlines announcing that “three people from Rajasthan” or “two people from Hyderabad” have made it to the top 2 percent appear regularly—almost always without context. “Unquestioning, putting it as the Stanford top 2% list,” Agrawal observed.

The result is a system where visibility replaces verification, and repetition stands in for rigour.

Rankings, Prestige, and the Illusion of Success

This uncritical acceptance of rankings is not limited to the Stanford list. Agrawal pointed to a striking example from global university rankings. “Times Higher Education once put IISc at 60th position in India in research quality,” he said. “Anyone would laugh at that. IISc is undoubtedly one of the best institutions in the country.”

Yet headlines rarely reflect such scepticism. Instead, rankings are framed as national achievements. Even political leadership has cited rising numbers of Indian universities in global rankings as evidence of progress.

“We need to change our measure of success”

“That cannot be a measure of success,” Agrawal warned. “If that is the measure we accept, then the distortions we see today are the outcome.”

A Call for Media Responsibility

The problem, experts argue, is not the existence of bibliometric datasets, but how they are communicated and consumed. Citation-based lists can serve useful analytical purposes when interpreted carefully. But when they are elevated into symbols of institutional excellence, without context or caveats, they risk misleading both the public and policymakers.

“We need to change our measure of success,” Agrawal concluded. “And the first step is for the media to stop reporting rankings as trophies, and start treating them as data that must be interrogated.”

The truth about the “Top 2% Scientists” list, then, is not that it is meaningless—but that its meaning has been repeatedly overstated. Used responsibly, it is one dataset among many. Used uncritically, it becomes a powerful illusion of prestige.

EDUNEWS & VIEWS

AI and Simulation Technologies Are Redefining Finance Classrooms Worldwide

Explore how AI and simulation-based learning are transforming finance and accounting education, bridging theory with real-world practice

The rapid expansion of digital technologies has profoundly transformed modern society. These advances have reshaped how individuals and institutions use technology to meet diverse needs and aspirations. Among the most impactful innovations is artificial intelligence (AI), which has catalysed social and educational transformations by simplifying complex challenges, enabling predictive simulations, and enhancing problem identification through modelling and scenario planning before decisions are made.

The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this digital transformation, compelling educational institutions to adopt online and hybrid learning models virtually overnight. This abrupt shift underscored the importance of digital competencies in accounting education while simultaneously revealing gaps in existing curricula and pedagogical methods.

AI now plays a pivotal role in teaching and learning across disciplines. Traditional classroom lectures and textbook exercises are increasingly being supplemented—or, in some cases, replaced—by AI-driven tools and interactive simulations. Collectively, these innovations are fostering a more immersive, adaptive, and forward-looking approach to financial education. In academic settings, AI facilitates rapid access to learning materials, delivers instant feedback, and supports autonomous learning, empowering students to achieve their academic goals more efficiently.

Artificial Intelligence–Driven Customisation in Financial Education

Despite growing recognition of the need for digitalisation in accounting education, a significant gap remains between the skills developed in academia and those demanded by industry. Finance and accounting disciplines are rooted in rigorous theoretical frameworks, quantitative analysis, and strict adherence to standards such as GAAP or IFRS. While textbooks and lectures provide foundational knowledge, they rarely reflect the complex and unpredictable decision-making environments that professionals face.

Students often experience limited exposure to market volatility, regulatory changes, and real-world uncertainty. Consequently, passive learning models that focus primarily on memorisation and theoretical understanding of topics such as risk management, portfolio optimisation, and forensic accounting are becoming less effective.

AI and simulation technologies are addressing this challenge by transforming classrooms into dynamic laboratories that mirror actual market and organisational contexts. The growing importance of sustainability reporting and integrated thinking further demands a technologically literate, systems-oriented approach to accounting education. Given the rapid evolution of the profession, it has become imperative to reassess and redesign finance and accounting curricula to prepare students for a digital-first future. However, a comprehensive understanding of how digitalisation reshapes learning outcomes and curricular design remains underdeveloped.

As early as the 1960s, educator Bert Y. Kersh developed a classroom simulator using films and stills to replicate classroom decision-making for pre-service teachers

AI-driven tools—such as ChatGPT, educational chatbots, Grammarly, Google Translate, and Microsoft Word’s intelligent features—are now ubiquitous in higher education. Their use must be critically evaluated, particularly in terms of data accuracy, transparency, and ethical implications.

Simulations: Bringing Theory into Practice

Simulation-based learning (SBL) serves as a bridge between academic theory and professional practice by recreating real-world environments and decision-making scenarios. In fields such as medicine and aviation, simulations have long been used to help students practise essential skills and solve complex problems safely. As early as the 1960s, educator Bert Y. Kersh developed a classroom simulator using films and stills to replicate classroom decision-making for pre-service teachers. A subsequent randomised control trial revealed that students trained through simulation reported higher self-efficacy and demonstrated “classroom readiness” three weeks ahead of their peers.

According to a 2023 report by the World Economic Forum, artificial intelligence is increasingly integral in accounting education, enhancing adaptive learning and student engagement.

In finance and accounting, simulation-based learning allows students to engage directly with financial instruments and business challenges, improving their proficiency in trading, budgeting, auditing, and decision-making. Virtual stock market trading, for example, enables students to manage portfolios using real-time or historical market data to understand risk, diversification, and market dynamics. Similarly, forensic accounting simulators expose learners to fraud examination and auditing techniques within controlled environments.

Comprehensive business simulations integrate finance, marketing, and operations, replicating complex decision-making processes and teamwork dynamics. These immersive exercises mimic the uncertainty and pressure of real-world financial contexts, helping students balance analytical precision with professional judgement. Moreover, because mistakes in simulations carry no real-world consequences, students can learn through trial and error—an invaluable process in developing professional competence and confidence.

Universities and professional training institutions worldwide are increasingly incorporating AI and simulation technologies into their curricula. Business schools, CPA training programs, and online finance courses now feature trading labs, AI-enabled auditing case studies, and gamified simulation platforms where students earn credit by solving complex, real-world problems.

Such experiential learning models align academic theory with professional practice, ensuring that graduates enter the workforce ready to thrive in a technology-driven economy. As digital disruption continues to reshape industries, these innovations hold the potential to produce not only skilled accountants and finance professionals but also visionary leaders equipped to navigate the complexities of the 21st-century financial landscape.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet