Know The Scientist

‘You’re admired, because no one understands you’

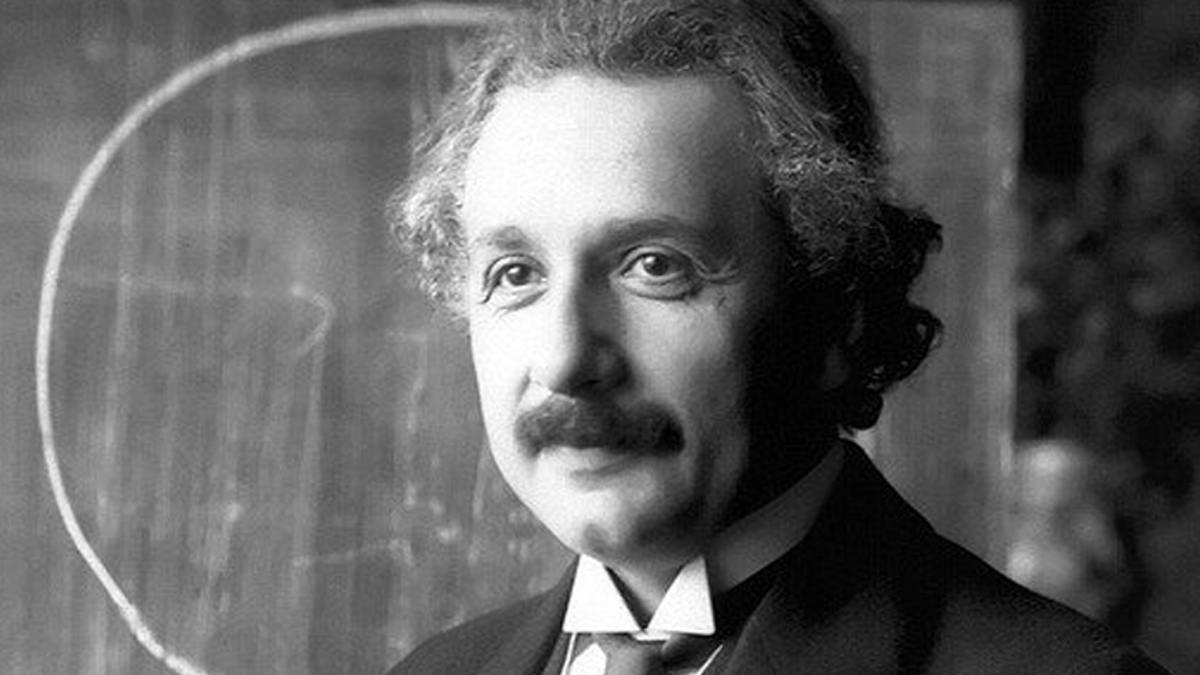

How does a soft-spoken, late-blooming, introspective young man—once dismissed as lazy and unimaginative—go on to become one of the greatest scientific minds the world has ever known? That story, woven with personal struggles, quiet determination, and an unmatched brilliance, is one of the most inspiring in the history of science. This edition of EP Know the Scientist turns the spotlight on the legend of Albert Einstein

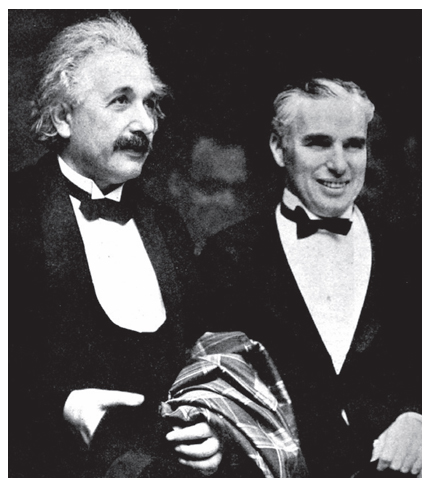

A Meeting of Geniuses

In 1931, two of the most brilliant minds of the 20th century met in Hollywood. One was Albert Einstein, the theoretical physicist who had turned our understanding of the universe on its head; the other, Charlie Chaplin, a master of silent cinema who could move the world to laughter without uttering a word.

“You’re admired because everyone understands you,” Einstein said to Chaplin.

“You’re admired,” Chaplin replied, “because no one understands you.”

That exchange perfectly captured the enigma of Einstein. Though his theories baffled the masses, his influence on science, and on the world itself, was impossible to ignore.

The Face of Modern Physics

Albert Einstein’s contributions to science redefined physics. From his Special and General Theories of Relativity to his explanation of the photoelectric effect, he reshaped how we understand energy, gravity, light, and time. His famous equation, E = mc², may be the most recognized scientific formula in history—a symbol of human curiosity and intellectual might.

Even today, astronomers rely on Einstein’s insights to decode gravitational waves, explain the bending of light around stars, and predict the paths of planets like Mercury. Long after his passing, Einstein continues to be a guiding force in scientific exploration.

A Curious Child

Born in 1879 in Ulm, Germany, to a middle-class Jewish family, Einstein was a quiet child. His parents worried because he spoke late. Teachers misunderstood his dreamy nature. But from a young age, Einstein was captivated by the invisible forces of the world. A simple compass given to him at age five stirred a lifelong fascination with unseen energies.

By 12, a book on Euclidean geometry filled him with awe. He called it his “sacred little geometry book,” and it gave him a glimpse of the order behind nature’s complexity.

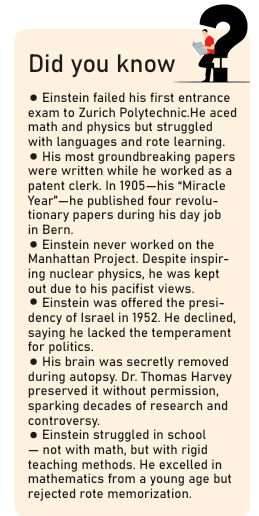

Despite a popular myth, Einstein was not bad at math. He excelled in mathematics and physics, though he struggled with the rigid, memorization-heavy Prussian education system. Creative thinking had little space in such classrooms—and Einstein needed space to think.

Failing to Fit, and Finding a Path

At 16, Einstein dropped out of school. He failed the entrance exam to Zurich’s prestigious Polytechnic School on his first try, performing well only in science and math. Undeterred, he studied on his own and passed the exam the following year.

After graduating in 1901, Einstein struggled to find work as a teacher. Eventually, he secured a job as a clerk at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern—a humble position that gave him time to think, scribble equations, and dream about the cosmos. It was during this period that Einstein’s revolutionary ideas took shape.

The Miracle Year

In 1905, while still a patent clerk, Einstein published four papers that would change the course of physics. He explained the photoelectric effect (which would win him the Nobel Prize in 1921), developed the Special Theory of Relativity, and introduced the idea of mass-energy equivalence. These ideas challenged Newtonian physics and formed the foundation of modern science.

At first, his work went unnoticed. But Max Planck, one of the leading physicists of the time, recognized Einstein’s genius. The world soon followed.

Fame, Flight, and Fear

By the 1910s, Einstein’s fame had spread far beyond academic circles. He was offered positions at the most prestigious universities across Europe. In 1915, he completed his General Theory of Relativity—a breathtaking explanation of gravity as the curvature of space-time.

But in 1933, as Hitler rose to power, Einstein fled Germany for the United States, renouncing his citizenship. The man dubbed the “Pope of Physics” took refuge in Princeton, New Jersey, where he would live and work for the rest of his life.

The Atom Bomb and Moral Dilemmas

Einstein’s equation E = mc² implied that immense energy could be released by splitting atoms. Though he was a lifelong pacifist, in 1939, fearing Nazi Germany’s nuclear ambitions, Einstein co-signed a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt urging research into atomic weapons.

Ironically, he was never part of the Manhattan Project. After World War II, horrified by the bomb’s use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Einstein became a leading voice against nuclear weapons.

The Man Behind the Mind

Einstein was more than a physicist. He was a violinist, a humanist, and an outspoken critic of nationalism and racism. Though famously disheveled, his mind was razor-sharp. In 1952, he was even offered the presidency of Israel—a role he declined, saying he lacked the experience and temperament for politics.

His personal life was complex. He married twice, had children, and endured heartbreaks, illnesses, and separations. Yet his work remained a constant force—until the very end.

The Brain that Fascinated the World

When Einstein died on April 18, 1955, at the age of 76, he refused life-prolonging surgery. “I want to go when I want,” he said. But the fascination with his mind didn’t end there. The doctor who performed his autopsy, Thomas Harvey, removed Einstein’s brain—without permission. He sliced it into hundreds of pieces, preserving them for study.

Later analyses suggested Einstein’s brain had unusual features—more folds, a larger inferior parietal lobe, and a higher ratio of glial cells. Some researchers believe these might explain his extraordinary cognitive abilities. But others warn against drawing conclusions from a brain no longer alive.

Regardless, Einstein’s mind remains a symbol of limitless human potential.

Legacy Eternal

Sixty-six years after his death, fragments of Einstein’s brain are still preserved in museums around the world. But his true legacy isn’t in physical remains—it’s in every scientific equation that bears his fingerprints, every telescope that bends light to measure distant stars, every classroom where young minds imagine the unimaginable.

In a world hungry for quick answers, Einstein stood for slow, deep thinking. “Imagination is more important than knowledge,” he once said. He gave us the tools to measure time and space—and the courage to wonder what lies beyond both.

Know The Scientist

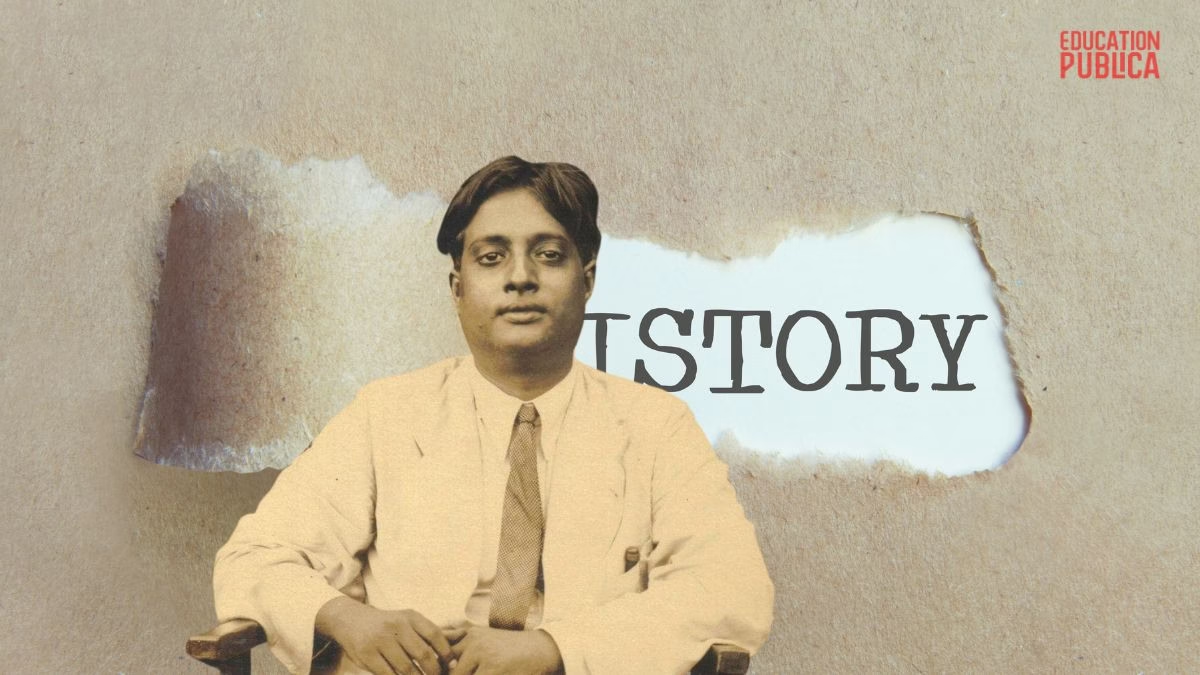

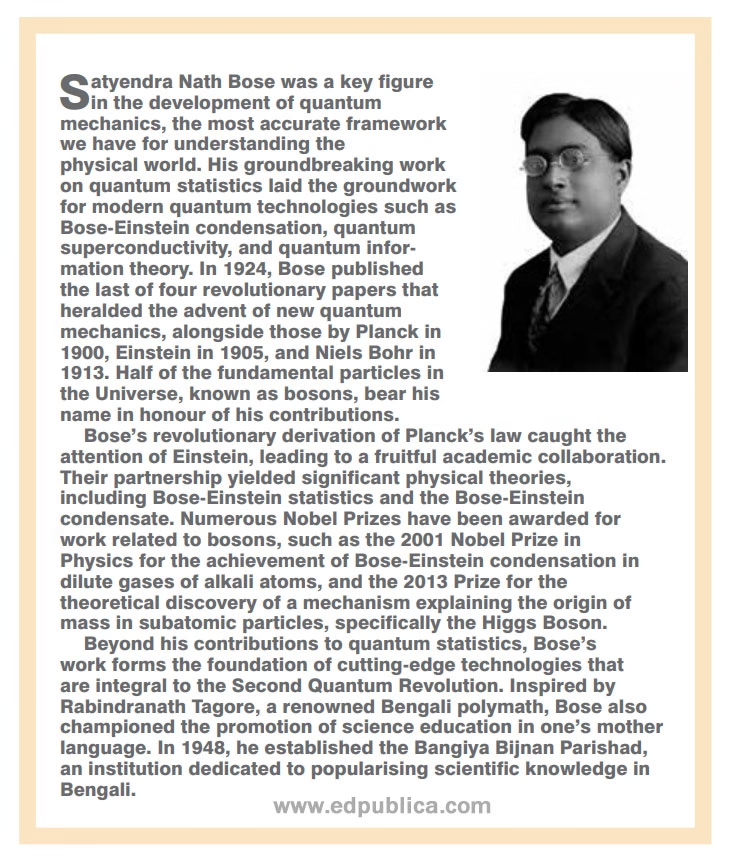

Remembering S.N. Bose, the underrated maestro in quantum physics

Rejected in Britain, celebrated by Einstein, here’s the story of S.N. Bose, the Indian physicist who formulated quantum statistics, now a bedrock theory in condensed matter physics.

It’s 1924, and Satyendra Nath Bose, going by S.N. Bose was a young physicist teaching in Dhaka, then British India. Grappled by an epiphany, he was desperate to have his solution, fixing a logical inconsistency in Planck’s radiation law, get published. He had his eyes on the British Philosophical Magazine, since word could spread to the leading physicists of the time, most if not all in Europe. But the paper was rejected without any explanations offered.

But he wasn’t going to give up just yet. Unrelenting, he sent another sealed envelope with his draft and this time a cover letter again, to Europe. One can imagine months later, Bose breathing out a sigh of relief when he finally got a positive response – from none other than the great man of physics himself – Albert Einstein.

In some ways, Bose and Einstein were similar. Both had no PhDs when they wrote their treatises that brought them into limelight. And Einstein introduced E=mc2 derived from special relativity with little fanfare, so did Bose who didn’t secure a publisher with his groundbreaking work that invented quantum statistics. He produced a novel derivation of the Planck radiation law, from the first principles of quantum theory.

This was a well-known problem that had plagued physicists since Max Planck, the father of quantum physics himself. Einstein himself had struggled time and again, to only have never resolved the problem. But Bose did, and too nonchalantly with a simple derivation from first principles grounded in quantum theory. For those who know some quantum theory, I’m referring to Bose’s profound recognition that the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution that holds true for ideal gasses, fails for quantum particles. A technical treatment of the problem would reveal that photons, that are particles of light with the same energy and polarization, are indistinguishable from each other, as a result of the Pauli exclusion principle and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle.

Fascinated and moved by what he read, Einstein was magnanimous enough to have Bose’s paper translated in German and published in the journal, Zeitschrift für Physik in Germany the same year. It would be the beginning of a brief, but productive professional collaboration between the two theoretical physicists, that would just open the doors to the quantum world much wider. Fascinatingly, last July marked the 100 years since Einstein submitted Bose’s paper, “Planck’s law and the quantum hypothesis” on his behalf to Zeitschrift fur Physik.

With the benefit of hindsight, Bose’s work was really nothing short of revolutionary for its time. However, a Nobel Committee member, the Swedish Oskar Klein – and theoretical physicist of repute – deemed it a mere advance in applied sciences, rather than a major conceptual advance. With hindsight again, it’s a known fact that Nobel Prizes are handed in for quantum jumps in technical advancements more than ever before. In fact, the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics went to Carl Wieman, Eric Allin Cornell, and Wolfgang Ketterle for synthesizing the Bose-Einstein condensate, a prediction made actually by Einstein based on Bose’s new statistics. These condensates are created when atoms are cooled to near absolute zero temperature, thus attaining the quantum ground state. Atoms at this state possess some residual energy, or zero-point energy, marking a macroscopic phase transition much like a fourth state of matter in its own right.

Such were the changing times that Bose’s work received much attention gradually. To Bose himself, he was fine without a Nobel, saying, “I have got all the recognition I deserve”. A modest character and gentleman, he resonates a lot with the mental image of a scientist who’s a servant to the scientific discipline itself.

But what’s more upsetting is that, Bose is still a bit of a stranger in India, where he was born and lived. He studied physics at the Presidency College, Calcutta under the tutelage that saw other great Indian physicists, including Jagdish Chandra Bose and Meghnad Saha. He was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, the highest civilian award by the Government of India in 1954. Institutes have been named in his honour, but despite this, his reputation has little if no mention at all in public discourse.

To his physicists’ peers in his generation and beyond, he was recognized in scientific lexicology. Paul Dirac, the British physicist coined the name ‘bosons’ in Bose’s honor (‘bose-on’). These refer to quantum particles including photons and others with integer quantum spins, a formulation that arose only because of Bose’s invention of quantum statistics. In fact, the media popular, ‘god particle’, the Higgs boson, carries a bit of Bose as much as it does of Peter Higgs who shared the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics with Francois Euglert for producing the hypothesis.

Know The Scientist

Narlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

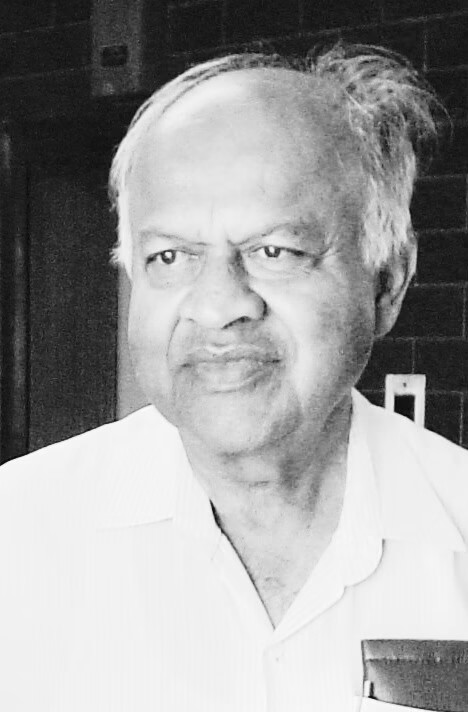

Jayant Narlikar has been one of the most prolific scientists, and science communicators India has ever produced. The octogenarian had died at his residence in Pune.

Jayant Narlikar passed away at his Pune residence on Tuesday. He was 86-years old, and had been diagnosed with cancer. With his demise, India lost a prolific scientist, writer, and institution builder.

In 2004, the government of India had honored Narlikar with the Padma Vibhushan, the second-highest civilian award, for his services to science and society. But that was not his first recognition from the Indian government. At the age of 26, he had received his first Padma Bhushan, in recognition for his work in cosmology, studying the universe’s large-scale structures. He helped contribute to derive Einstein’s field equations of gravity from a more general theory. That work, dubbed the Narlikar-Hoyle theory of gravity, was borne out a collaboration with Narlikar’s doctoral degree supervisor at Cambridge; Fred Hoyle, the then leading astrophysicist of his time.

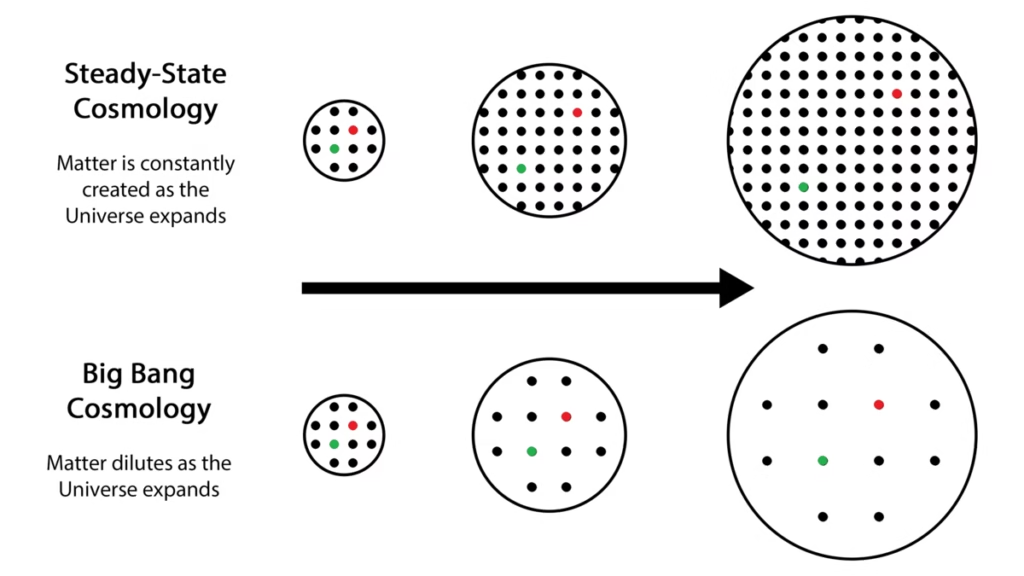

Narlikar and the steady-state theory

Narlikar and Hoyle bonded over a shared skepticism towards the prevalent Big Bang hypothesis, which sought to extrapolate the universe’s ongoing expansion to its birth at some finite time in the past. However, Narlikar and Hoyle could not have been more opposed, mostly out of their own philosophical beliefs. They drew upon the works of 19th century Austrian physicist and philosopher, Ernest Mach, in rejecting a theory discussing the universe’s beginning in the absence of a reference frame. As such, Narlikar was a strong proponent of Hoyle’s steady-state model of the universe, in which the universe is infinite in extent, and indefinitely old. As such, the steady-state theorists explained away the universe’s expansion to matter being spawned into existence from this vacuum at every instant, aka a C-field.

However, the steady-state’s predictions did not hold up in face of evidence the universe expands over time. Nor did its successive avatar, the quasi-steady state theory devised sway scientific consensus. The death knell came when evidence of the cosmic microwave background (aka the CMB) was discovered in 1964.

Despite steady-state’s failure, it provided healthy rivalry to the Big Bang from the 1940s to the 60s, providing opportunities for astronomers to compare observations to precise predictions. In the words of the Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg, “In a sense, this disagreement is a credit to the model; alone among all cosmologies, the steady state model makes such definite predictions that it can be disproved even with the limited observational evidence at our disposal.”

The Kalinga winning short-story writer

Narlikar was more than just a cosmologist, studying the large-scale structure of the universe. He also had been an acclaimed science fiction writer, with his works penned in English, Hindi, and in his vernacular, Marathi. His famous work was a short-story, Dhoomekethu (The Comet), revolving around themes of superstition, faith, rational and scientific thinking. Published in Marathi in 1976, with translations available in Hindi, the story was adapted later into a two-hour film bearing the same name. In 1985, the film aired on the state-owned television broadcasting channels, Doordarshan.

In a way, he was India’s Carl Sagan, airing episodes explaining astronomical concepts, with children being his target audience. The seventeen-episode show, Brahmand (The Universe), aired in 1994, to popular acclaim. One of his most popular books, Akashashi Jadle Nathe (Sky-Rooted Relationship), remains popular. An e-book version in Hindi is available on Goodreads, with 470 reviewers lending an average rating of 4.7 out of 5.

His efforts was honored with an international prize. In 1996, he received the much-coveted Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science, awarded annually in India by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), “in recognition of his efforts to popularize science through print and electronic media.” Narlikar had been only the second Indian at the time, after the popular science writer Jagjit Singh, to have received the award.

When Narlikar returned to India, accepting a position at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), he realized that the fruits of astrophysical research did not flourish outside central institutions. Though Bengaluru had an Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Narlikar envisioned basing a research culture paralleling his time at Cambridge. Hence, the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) was born in 1988, and Narlikar was appointed its founding director. Arguably, his most visible legacy would have been to shape India’s astrophysical research culture through his work with the IUCAA (pronounced “eye-you-ka”).

Space & Physics

Dr. Nikku Madhusudhan Brings Us Closer to Finding Life Beyond Earth

Dr. Madhusudhan, a leading Indian-British astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge, has long been on the frontlines of the search for extraterrestrial life

Somewhere in the vast, cold dark of the cosmos, a planet orbits a distant star. It’s not a place you’d expect to find life—but if Dr. Nikku Madhusudhan is right, that assumption may soon be history.

Dr. Madhusudhan, a leading Indian-British astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge, has long been on the frontlines of the search for extraterrestrial life or what we call the alien life. This month, his team made headlines around the world after revealing what could be the strongest evidence yet of life beyond Earth—on a distant exoplanet known as K2-18b.

Using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, Madhusudhan and his collaborators detected atmospheric signatures of molecules commonly associated with biological processes on Earth—specifically, gases produced by marine phytoplankton and certain bacteria. Their analysis suggests a staggering 99.7% probability that these molecules could be linked to living organisms.

“This marked the first detection of carbon-bearing molecules in the atmosphere of an exoplanet located within the habitable zone,” the University of Cambridge said in a press statement. “The findings align with theoretical models of a ‘Hycean’ planet — a potentially habitable, ocean-covered world enveloped by a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.”

Born in India, Dr. Madhusudhan began his journey in science with an engineering degree from IIT (BHU) Varanasi

In addition, a fainter signal suggested there could be other unexplained processes occurring on K2-18b. “We didn’t know for sure whether the signal we saw last time was due to DMS, but just the hint of it was exciting enough for us to have another look with JWST using a different instrument,” said Professor Nikku Madhusudhan in a news report released by the University of Cambridge.

The man behind the mission

Born in India, Dr. Madhusudhan began his journey in science with an engineering degree from IIT (BHU) Varanasi. But it was during his time at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the mentorship of exoplanet pioneer Prof. Sara Seager, that he found his calling. His doctoral work—developing methods to retrieve data from exoplanet atmospheres—would go on to form the backbone of much of today’s planetary climate modeling.

Now a professor at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, Madhusudhan leads research that straddles the line between science fiction and frontier science.

A Universe of Firsts

Over the years, his work has broken new ground in our understanding of alien worlds. He was among the first to suggest the concept of “Hycean planets”—oceans of liquid water beneath hydrogen-rich atmospheres, conditions which may be ideal for life. He also led the detection of titanium oxide in the atmosphere of WASP-19b and pioneered studies of K2-18b, the same exoplanet now back in the spotlight.

His team’s recent findings on K2-18b may be the closest humanity has ever come to detecting life elsewhere in the universe.

Accolades and impact

Madhusudhan’s contributions have earned him global recognition. He received the prestigious IUPAP Young Scientist Medal in 2016 and the MERAC Prize in Theoretical Astrophysics in 2019. In 2014, the Astronomical Society of India awarded him the Vainu Bappu Gold Medal for outstanding contributions to astrophysics by a scientist under 35.

But for Madhusudhan, the real reward lies in the questions that remain unanswered.

Looking ahead

Madhusudhan cautions that, while the findings are promising, more data is needed before drawing conclusions about the presence of life on another planet. He remains cautiously optimistic but notes that the observations on K2-18b could also be explained by previously unknown chemical processes. Together with his colleagues, he plans to pursue further theoretical and experimental studies to investigate whether compounds like DMS and DMDS could be produced through non-biological means at the levels currently detected.

Beyond the lab, Madhusudhan remains dedicated to mentoring students and advancing scientific outreach. He’s a firm believer that the next big discovery might come from a student inspired by the stars, just as he once was.

As scientists prepare for the next wave of data and the world watches closely, one thing is clear: thanks to minds like Dr. Nikku Madhusudhan’s, the search for life beyond Earth is no longer a distant dream—it’s a scientific reality within reach.

-

Society1 month ago

Society1 month agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth3 months ago

Earth3 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Women In Science4 months ago

Women In Science4 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet