Women In Science

How Dr. Julia Mofokeng is Rewriting the Story of Plastic Waste

Her innovative research on biodegradable polymers offers a promising solution to the global plastic pollution crisis

EP WOMEN IN SCIENCE introduces Dr. Julia Puseletso Mofokeng from South Africa, whose journey from research assistant to respected scientist reflects her perseverance and dedication to the field of science. Her innovative research on biodegradable polymers offers a promising solution to the global plastic pollution crisis. These large, chain-like molecules provide an environmentally friendly alternative to petroleum-based plastics. Dr. Mofokeng’s story will undo-ubtedly inspire more women to pursue and excel in scientific careers.

Julia Puseletso Mofokeng, a Senior Lecturer and Researcher in the Department of Chemistry at the University of the Free State (UFS), is contributing to the global fight against plastic pollution through her innovative research on biodegradable polymers—large, chain-like molecules that provide an environmentally friendly alternative to petroleum-based plastics. As she advances her research into polymers that degrade naturally, Dr. Mofokeng is playing a crucial role in addressing one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time.

A Spark of Curiosity: The Early Years

Dr. Mofokeng’s path to becoming a scientist was anything but typical. Her journey began not in a traditional ecosystem but in a research laboratory at the University of the North, Qwaqwa Campus, in 1999. “I was appointed as a Research Assistant, responsible for cleaning the postgraduate research labs,” she recalls. “But it wasn’t just cleaning—I became fascinated by the experiments and projects the researchers were working on.”

The laboratory was a vibrant place, with researchers studying a variety of topics, including anti-cancer drugs and polymer science. “I would clean quickly so I could watch them work. They were kind enough to let me help with some tasks, and over time, I learned a lot from them. It sparked something in me,” Dr. Mofokeng explains.

Her passion for science blossomed even though she had no formal science background from secondary school. The experience ignited her curiosity, leading her to pursue an undergraduate degree in chemistry. “At first, I didn’t think I could study science at a university level, but my mentors saw potential in me. They encouraged me to keep going and helped me realize that I could pursue a career in this field,” she says.

In 2003, after the University of the Free State merged with Qwaqwa Campus, Dr. Mofokeng was able to enroll in the Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.) degree program, beginning with the Extended Program due to her non-traditional academic background. “It was a struggle, but I worked hard. My mentors, particularly Prof. Joseph Bariyanga, pushed me to keep learning and growing,” she recalls.

From Research Assistant to Researcher

By 2008, Dr. Mofokeng had completed her B.Sc. degree and decided to pursue an Honours degree in Polymer Science. It was during this time that she began to focus on the environmental issues that would shape her career. “I had always been concerned about plastic waste in my community. I realized that finding alternatives to petroleum-based plastics could help address this growing environmental problem,” Dr. Mofokeng shares.

Her decision to pursue biodegradable polymers was driven by a personal desire to contribute to environmental sustainability. She embarked on her Honours research project under the guidance of Dr. Buyiswa Hlangothi, exploring thermoplastic starch sourced from corn starch for possible applications in packaging. “My research involved studying biodegradable polymers that could replace petroleum-based plastics, and I felt this was an area where I could make a real impact,” she says. This research formed the foundation of her Masters and eventually PhD work.

Her Masters research, conducted under the supervision of Prof. Adriaan Luyt, took her to Hungary in 2009, where she worked on a collaborative project comparing biodegradable Polylactic Acid (PLA) and petroleum-based Polypropylene (PP) polymers. The focus was to see if PLA could replace PP for short-shelf-life applications, a common use for disposable plastics. “The results were promising, and it was an eye-opening experience. While in Hungary, I had the opportunity to witness the production of biodegradable packaging materials, like water bottles and toothbrushes, made from PLA and thermoplastic starch,” she recalls.

Her work during this time led to her MSc degree in Polymer Science in 2011, and one of her first research papers gained significant attention, receiving over 370 citations on Google Scholar to date. “That publication was a turning point for me,” she says. “It motivated me to continue pushing the boundaries of what was possible with biodegradable polymers.”

In 2011, Dr. Mofokeng began her PhD research, focusing on biodegradable polymer blends and nanocomposites, using titania as a filler. Over the next few years, she published five successful research articles, contributing to her growing reputation as an expert in the field of polymer science. “The success of my research was rewarding, but what mattered most was that it could contribute to solving a major environmental problem,” she says.

Challenges and Triumphs

As a woman in science, Dr. Mofokeng has faced her share of challenges, particularly the lack of female mentors in the early years of her career. “The lack of women mentors and leaders available growing up, made me think and believe that certain positions are made for men only. It was not easy to find strong women role models in my early years of figuring out what I wanted to do,” she admits. However, things began to change as she moved through her university studies, especially in the science faculty, where her lecturers were predominantly female. “Surprisingly my lectures were mostly women. That encouraged me to study hard and succeed because I now had women role models I looked up to,” she says.

Despite the encouraging presence of female mentors, Dr. Mofokeng’s journey wasn’t without its difficulties. “When I started studying at the university, particularly in the science faculty where the student population was dominated by males, surprisingly my lectures were mostly women. That encouraged me to study hard and succeed because I now had women role models I looked up to,” she recalls. “When I was doing my honours degree, I was the only female student in a class of six. I found myself in a research group with very few women, which was a stark contrast to the male-dominated environment I was used to,” she recalls. “When we had international visitors to our institution, I realized that out of a group of 18, I was the only woman, apart from my two lecturers.”

This realization motivated Dr. Mofokeng to change the narrative. “I decided that if I wanted to see more women in science, I had to be that role model,” she says. She began speaking at events and creating awareness through social media. “I started posting about my milestones—my graduations, my international research experiences, and my achievements—in order to inspire other women to pursue science.”

Her efforts paid off. “The student population in our department has changed. Today, we have many more female students in science, and they are excelling,” she says with pride.

Biodegradable Polymers for Environmental Sustainability

Dr. Mofokeng’s current research focuses on the development of fully biodegradable polymer blends and nanocomposites, designed to address plastic pollution and environmental degradation. “Plastic pollution is a serious global issue. Each year, between 19 to 23 million tonnes of plastic waste leak into aquatic ecosystems, causing significant harm to marine life and ecosystems,” she explains.

Her work aims to offer a sustainable alternative to petroleum-based plastics, which are notoriously difficult to break down in the environment. “We are developing biodegradable polymers that not only degrade naturally but also have enhanced properties for practical applications,” Dr. Mofokeng explains. “We’re working with a variety of materials—natural fibers, inorganic fillers, and even carbon-based composites—to improve the strength, thermal properties, and flame retardancy of the polymers.”

One of Dr. Mofokeng’s most exciting projects involves using biodegradable polymers to help remove heavy metals from contaminated water. “We are exploring the use of graphene oxide combined with biodegradable polymer blends to remove contaminants like lead from water. This has the potential to address environmental issues in communities where polluted water is a major problem,” she says.

Her work is already yielding significant results, with several articles published in high-impact journals. “The goal is to develop polymers that can be used not only in packaging but also in other critical areas such as medical devices, water purification, and even aerospace materials,” Dr. Mofokeng shares.

Shaping the Future

Looking ahead, Dr. Mofokeng is focused on expanding her research and mentoring future generations of scientists. “In the next five years, I want to see my research making a direct impact in communities, particularly in Bophelong and Qwaqwa, where plastic pollution is a major issue,” she says. She envisions a world where her research helps communities reduce waste and adopt more sustainable practices. “I also want to continue mentoring young women and men who aspire to work in science and technology,” she adds.

Dr. Mofokeng has also set ambitious goals for her career. “I’m working towards becoming an Established Researcher in the next few years, with the long-term goal of becoming a full Professor of Chemistry and Polymer Science,” she reveals. “I want to expand my research group and establish even more international collaborations, particularly in the areas of biodegradable materials and environmental sustainability.”

Dr. Julia Puseletso Mofokeng’s journey from a research assistant to a respected science researcher is an inspiring tale of perseverance, passion, and dedication to both science and community. Her research on biodegradable polymers holds the potential to address the global crisis of plastic pollution, while her commitment to mentoring young scientists is helping to shape the next generation of innovators. Her legacy will undoubtedly inspire countless women to follow in her footsteps and make their own mark in the world of science.

Women In Science

Women in STEM Need Systemic Change

Stay committed, stay curious, and never underestimate the impact your work can have on the world

Despite notable gains in women’s participation in science careers in South Africa, women remain underrepresented across STEM fields. While more women are graduating from universities, studies continue to show that men dominate science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers — a gap that is even more pronounced among Black women. Although women form the majority of young university graduates nationally, only about 13% of STEM graduates are women, and Black women remain significantly underrepresented in senior academic and research leadership positions.

These disparities stem from systemic barriers including gender bias, limited access to mentorship, and inconsistent availability of resources. Such obstacles continue to hinder the full and equitable participation of women in scientific careers.

At the University of the Free State (UFS), where I work, there is a growing institutional commitment to support emerging researchers — particularly women — through mentorship and research development initiatives. This aligns with Vision 130, which aims to foster research excellence and increase societal impact. I am fortunate to be part of the university’s Transformation of the Professoriate Mentoring Programme, designed to build a strong cohort of emerging scholars. The programme provides academic and research mentorship, supports access to networking and funding opportunities, and nurtures candidates toward assuming senior academic and research roles. It also helps lay the groundwork for future centres of research excellence.

Those of us who benefit from such opportunities carry a responsibility to extend mentorship to more women researchers, especially from underrepresented groups. Expanding women’s participation in science requires addressing the barriers that continue to limit progress. Key interventions include expanding mentorship and networking opportunities, increasing financial support and scholarships for women in STEM, and promoting national policies that support work–life balance and the needs of working mothers.

There is also an urgent need to raise awareness about women’s contributions to science and challenge persistent stereotypes that discourage girls from pursuing scientific careers. Building inclusive, diverse work environments where women feel valued and supported is essential to increasing both participation and retention. Progressive policies that promote the employment of Black women academics in STEM leadership roles are also critical. A diverse cohort of women in authority can provide gender-sensitive mentorship and create pathways for future scholars.

Pursuing a career in science demands hard work, resilience, and a commitment to continuous learning. It is a challenging journey, but deeply rewarding for those passionate about contributing to the advancement of humanity through research. It requires uncovering new insights, developing innovative solutions, and sharing knowledge that can transform lives. Marie Curie captured this spirit beautifully when she said, “I am among those who think that science has great beauty… like a fairy tale.” This sense of wonder should fuel every aspiring researcher.

Science is also fundamentally collaborative. Seek mentors, build networks, remain humble, and embrace learning from others. Your contributions — even those that seem small — form part of a larger scientific story that future generations will build on. If you are driven by curiosity, purpose, and a desire to contribute to the greater good, a career in science may be the path for you…

Interviews

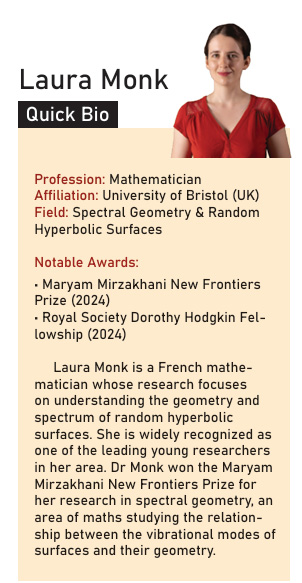

Geometry, Curiosity and Finding ‘Her’ Place

Dr Laura Monk has quickly become one of the field’s most exciting young geometers

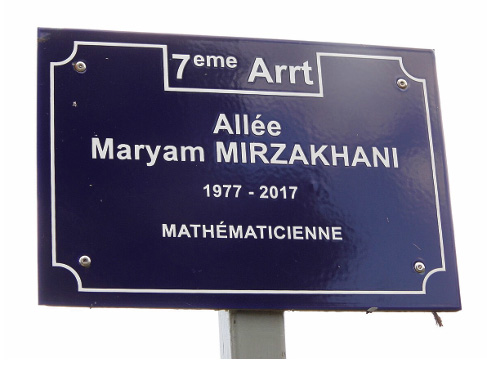

In modern mathematics, where imagination meets deep abstraction, Dr Laura Monk has quickly become one of the field’s most exciting young geometers. In 2024, she was awarded the Maryam Mirzakhani New Frontiers Prize, an honour regarded as one of the most prestigious recognitions for early-career women mathematicians and presented at the Breakthrough Prize ceremony—often called the “Oscars of Science.” A mathematician whose work explores the geometry of negatively curved spaces, Monk’s path into the field was shaped not only by intellectual fascination but also by uncertainty, self-doubt, and the search for belonging—a journey familiar to many women in STEM. Growing up in France, she found early encouragement from teachers who pushed her to think harder and explore deeper. Later, mentors like Nalini Anantharaman and the pioneering legacy of Iranian math genius Maryam Mirzakhani helped her see that mathematics could be a creative, expansive world—not an exclusive club.

A Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow and Lecturer at the University of Bristol, Monk works on the geometry of negatively curved spaces and the behaviour of objects moving within them. In this conversation with Dipin Damodharan, she speaks candidly about intuition, representation, hyperbolic geometry, and the courage required to stay in mathematics when you’re not sure you fit.

‘Go for it! Math is super cool and useful’

To start with, could you tell us how your journey in mathematics began? Was there a defining moment when you realised this would become your life’s work?

I always enjoyed mathematics at school and thought it would be a good idea to study it, as I was interested in it and it opens the door to many jobs. After my first two years of study, I realized I loved the subject itself more than the idea of finding a job using it, and decided I wanted to work in mathematics (probably as a teacher).

I faced many challenges and doubts—I somehow never felt sure mathematics was “for me,” even though I loved it. But I’m very happy I stuck with it and made a few leaps of faith at the right times. At the end of my master’s, I decided to start a PhD because it is required for certain higher education teaching positions in France. I thought: three years is a lot of time, better get excited and really go for it! Luckily, I met my PhD advisor, Nalini Anantharaman, who introduced me to a fascinating research project.

The way she ventured into different areas of mathematics, tackling ambitious new projects with no apparent fear, was an incredible inspiration. She was very different from the image I had of “the mathematician.” Her mentorship made me feel confident I could do it if I wanted to. And then I did!

Growing up in France, were there specific teachers, mentors, or institutions that played a pivotal role in shaping your mathematical thinking?

Mathematics is taught and shared, and I have many teachers to thank for my mathematical upbringing. My high-school teacher had extremely high standards and told me off a few times for doing the minimum instead of pushing myself. My second-year teacher gave me a first glimpse of how exciting venturing into the unknown can be during a research project.

One of the ways maths is taught in France is through a two-year intensive preparatory school followed by further studies at university. I found this structure gave me a strong basis to build on, as well as methods to organize myself and work well.

What were some of the challenges you faced as a young woman entering a field often dominated by men? How did you navigate them?

Mathematics is, indeed, a very masculine field, and one could imagine sexist behaviours to be common. I have to say, luckily perhaps, that this has not been my experience. I have always felt extremely welcomed into this community, whether as a student or a researcher.

However, I did still struggle very much as a student with finding a sense of place and purpose in what I was doing. Though these difficulties are quite universal, I think they were amplified by being one of the only girls in my cohort. Identifying this was very helpful in overcoming these feelings, because it led me to build strong connections with my peers, to find female mentors and role models, and to invest myself in events for young women, all of which helped tremendously.

Much of your work lies at the intersection of geometry and dynamics. Could you explain your research focus in simple terms?

I study certain types of surfaces called “hyperbolic surfaces.” Unlike a piece of paper (which is flat) or a sphere (which is positively curved), hyperbolic surfaces have negative curvature: they look like Pringles. There exist many, many hyperbolic surfaces, and they appear in very different fields of mathematics: number theory, mathematical physics, dynamics…

I am trying to understand what these surfaces “look like” a bit better. In order to do so, I put all of them in a (big) bag, take one at random, and try to describe it.

Mathematics often requires deep abstraction. How do you stay connected to the beauty or “reality” behind these abstractions?

I relate more to the beauty than the reality! To me, mathematics is a gigantic world that we are building or exploring together. I find a lot of joy in how different parts of this world interact and how bridges can be built; simple ideas can come together from far apart and create something new.

What role does intuition play in your mathematical process?

A big role! One of the reasons why I have been drawn to mathematics is that, once you understand a formula or a theorem, you don’t really need to memorize it by heart anymore: it just makes sense. When I learn something new, I go through a lengthy process of unravelling everything and I often feel very confused (or sometimes even a bit desperate!).

But, one day, all of a sudden, everything becomes clear, to the extent that it is even hard to remember why I was so lost initially. I think this is one of the reasons why it is so hard for us to share and convey what we do to one another, or to the general public.

Maryam Mirzakhani’s groundbreaking work in geometry and moduli spaces continues to inspire mathematicians globally. In what ways has her work influenced your own research? You have worked on topics that build upon or are inspired by Mirzakhani’s legacy. Could you speak about this continuity—how do you see her influence evolving in your field?

Maryam Mirzakhani created my research field, and I have studied a certain part of her work in great detail. My research consists in picking a hyperbolic surface at random and looking at it. She was one of the first people to have had this amazing idea. At the time, there existed a probability model allowing one to pick hyperbolic surfaces at random, but it was completely abstract and unusable.

Through several beautiful breakthroughs, she created a method that made this possible. We are still at the beginning of the wide variety of applications following from these advances.

If you could give a message to a young girl fascinated by numbers but unsure about pursuing math, what would you say?

Go for it! Math is super cool and useful, so you will have loads of fun and learn a lot. It is ok if you don’t identify with the image of the “math guy”; there are a lot of ways to enjoy math. It is not just about proving theorems or solving exercises, it is about creativity and sharing.

Outside of mathematics, what brings you joy or fuels your curiosity?

I quite like jigsaw puzzles and knitting, both of which relax me and make me appreciate how a lot of little steps can come together to create something big. Right now, my main source of joy is my two-year-old daughter, and seeing her discover the world. If only we could stay this curious and observant about every single little thing!

Do you think artificial intelligence and computers are changing the way we do mathematics?

Computers definitely have! We used to pay people to perform long lists of computations for researchers, and to publish entire books of randomly generated numbers in order to study probabilities. Now both of these activities seem very silly. Mathematicians use computers all the time, whether to perform experiments, find the answer to a simple question, or write and share their work.

I personally choose to be optimistic about the future of AI. You would have a very hard time conveying to someone in 1980 the role that computers play in everyone’s lives, but for mathematics, they have greatly enlarged our experience and allowed us to go faster, further. Things are scary now because we do not know what is ahead of us.

Women In Science

The Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

Despite two decades of progress, women remain just one in three researchers worldwide. Global datasets reveal how systemic filters — from classrooms to laboratories and limited mentorship access — continue to push women to the margins of science

When a young astrophysicist in Buenos Aires packed up her telescope after her PhD, she had every intention of continuing her research. Five years later, she works in data analytics, far from the night skies she once studied.

EdPublica met her by chance at Kuala Lumpur airport. Her story is echoed across continents — from lab benches in Lagos to computing centres in Bengaluru — where women enter science full of promise, only to find themselves on the margins of it.

According to UNESCO’s latest data, only one in three researchers worldwide is a woman — a number that has barely moved in two decades. For all the progress in girls’ education and gender equality elsewhere, science — the very field meant to advance humanity — remains caught in an old equation that continues to leave women out.

The slow revolution

‘UNESCO’s Status and Trends of Women in Science (2025)‘ reveals a striking paradox: more women than ever are pursuing higher education, yet their presence in scientific research and leadership has barely expanded.

Globally, women account for about 35 percent of graduates in STEM fields, but that average conceals deep divides. In life sciences, they have reached near parity. In engineering, physics, and computing, their numbers plummet below a quarter.

“Girls are not opting out of science,” says Shamila Nair-Bedouelle, UNESCO’s Assistant Director-General for Natural Sciences. “They are being filtered out by systems that were never designed for them.”

That “filter” begins early. Subtle stereotypes about what girls are “good at” shape subject choices long before university. The absence of visible role models compounds the message.

Dr. Julia Puseletso Mofokeng, Senior Lecturer in Chemistry at the University of the Free State, South Africa, recalls that absence vividly:“When I was doing my honours degree, I was the only female student in a class of six. Later, in a research group, I found myself surrounded by men. During international collaborations, out of 18 participants, I was the only woman. That realization motivated me — I decided that if I wanted to see more women in science, I had to be that role model,” she tells EdPublica.

Her reflection captures a global truth: women’s participation rises where mentorship and visibility intersect. Where they don’t, even ambition finds itself isolated.

From classrooms to corridors of power

Getting a degree is only the first hurdle. The next — and far harder — challenge is staying in the system. UNESCO data show that women hold just one-third of research positions globally, dropping to around 22 percent in G20 nations.

In industrial and corporate R&D, the numbers shrink further. Temporary contracts, uneven access to grants, and opaque promotion systems form invisible barriers. Even where hiring begins on equal footing, women’s participation thins out with every rung of seniority.

A 2025 bibliometric analysis of 80 million scientific papers found that men dominate the top ten percent of most productive and cited researchers in almost every field. Women start at comparable rates but face higher attrition and fewer opportunities to lead multi-author studies or secure large grants.

“Science is not short of capable women,” says Dr. Claudia Ntsapi, a researcher at the University of the Free State, in conversation with EdPublica.

“Systemic barriers — gender bias, lack of mentorship, limited resources — continue to hinder true equality in science careers.”

She points to South Africa’s paradox: women make up the majority of university graduates, yet only 13 percent of STEM graduates are women, and Black women remain severely underrepresented in leadership.

“We need mentorship networks, scholarships, and policies that promote work-life balance. And we must raise awareness about the contributions of women in science to challenge the stereotypes that keep girls away,” Dr. Claudia adds.

The gender of knowledge

The problem, UNESCO argues in its Call to Action: Closing the Gender Gap in Science (2024), is not merely one of representation — it’s one of perspective. Who participates in science shapes what science studies, and how it studies it.

When most clinical research was designed around male physiology, women’s health outcomes suffered. When engineers ignored how climate disasters displace caregivers, adaptation models missed critical social realities.

“Science cannot be sustainable if it is exclusive,” UNESCO notes. “Gender equality is a prerequisite for scientific excellence.”

Mathematician Professor Neena Gupta, recipient of the Infosys Prize 2024 in Mathematical Sciences, agrees that inclusion isn’t charity — it’s strength. In her interview with EdPublica, says, “Women constitute half of our strength and are equally capable of contributing to science and mathematics. But they often shoulder additional family responsibilities. With the right support — from family, government, and institutions — women can contribute freely to science and technology.”

Why women leave

Behind the statistics are systems built on old assumptions — that a researcher’s productivity must be uninterrupted, that career gaps signal lack of commitment, that caregiving is a private burden.

Across countries, more than 70 percent of women in research are on temporary or part-time contracts, compared to 55 percent of men. When funding tightens, they are often the first to go. Maternity leave resets grant eligibility. Mentorship networks skew male, perpetuating cycles of exclusion.

Dr. Laura Monk, a Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow and Lecturer at the University of Bristol (UK), captures this invisible struggle, “Mathematics is indeed a very masculine field. I’ve been lucky not to face overt sexism, but I struggled deeply as one of the only girls in my cohort. Finding female mentors and peers was crucial — it gave me a sense of belonging and purpose. That’s what many young women lack: the feeling that they belong here.”

Professor Neena Gupta echoes that sentiment from India’s perspective, “there are now more women in mathematics than there were earlier, and the number is growing. Having role models helps. We must continue supporting these women so young girls can see proof that they too can succeed.”

Flickers of progress

Still, the global picture is not uniformly bleak. Central Asia now hovers near gender parity in research, and Latin America’s public research systems have pushed women’s representation close to 45 percent. Eastern Europe has stabilized near 40 percent.

In Asia, change is slower but visible. India reports that 43 percent of PhD students are women, yet only about 18 percent work in industrial R&D. Government initiatives like KIRAN, Vigyan Jyoti, and SERB’s POWER grants are slowly rewriting that equation by funding re-entry fellowships and supporting mid-career researchers.

“I have faced the challenges most women face — balancing family, raising children,” says Professor Gupta. “But I was fortunate to have a supportive family that shared my responsibilities. That support made it possible for me to focus on research.”

Her story, echoed in laboratories across continents, underlines a pattern: where family and institutional support converge, women stay and thrive. Where they don’t, science loses talent it cannot afford to waste.

Leadership and the glass microscope

If entry and retention are the first two bottlenecks, leadership is the third. Less than 15 percent of national science academy fellows are women. Nobel Prizes, large-scale grants, and directorships of major research facilities remain overwhelmingly male.

Promotion criteria reward uninterrupted publication and global visibility — metrics that inherently penalize those who take career breaks. “It’s not that women aren’t producing excellence,” UNESCO notes. “It’s that the system measures excellence through a lens that erases them.”

The Call to Action lays out a clear roadmap: transparent promotion processes, gender audits for research grants, institutional accountability, and gender-responsive budgeting. It calls on governments to publish annual data — because what isn’t measured isn’t fixed.

India in the global equation

India’s story sits at the intersection of progress and persistence. Female enrolment in STEM has surged, and the country now ranks among the top producers of women science graduates. Yet in leadership, the gap yawns wide.

Only one in four senior faculty positions in India’s universities is held by a woman. In industrial research, that number drops to one in five. Cultural expectations and workplace rigidity continue to limit re-entry for mid-career women.

But India’s policy landscape offers lessons: the Department of Science and Technology’s women-focused grants, INSPIRE fellowships, and the inclusion of gender equity in the National Science and Technology Policy draft all point toward systemic change — if implementation follows intent.

Why it matters now

Women’s equal participation in science is not a “women’s issue.” It is a scientific, developmental, and democratic imperative. Every dataset or discovery that excludes half the population leaves the world poorer in ideas.

UNESCO’s twin reports — one analytical, one urgent — make the same argument: the gender gap in science is measurable, correctable, and indefensible. Closing it is not about fairness alone; it is about unlocking the full imagination of science itself.

As Dr. Mofokeng puts it, “if I wanted to see more women in science, I had to be that woman.”

The next generation shouldn’t have to say the same.

Note: This story is part of the EdPublica Women in Science Initiative, an ongoing global editorial effort to document the data, experiences, and policies shaping women’s participation in research and leadership. The series celebrates women in science while examining mentorship networks, policy interventions, and structural inequalities in depth. Readers and researchers are invited to share insights or stories with EdPublica’s Women in Science Desk, contact@edpublica.com, or dipin@edpublica.com

-

Society4 weeks ago

Society4 weeks agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth3 months ago

Earth3 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society1 month ago

Society1 month agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Women In Science4 months ago

Women In Science4 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet