Society

As Oppenheimer wins the Oscars, here is an epiphany

We can’t unmix science from politics. They’re intertwined.

Earlier today, Christopher Nolan’s much acclaimed film, Oppenheimer (2023), won 7 awards at the Oscars – including Best Picture, Actor, Supporting Actor, Score, Cinematography, Editing and Director.

And what better moment can there be to discuss threats and fears about the wildest creations of nuclear physics?

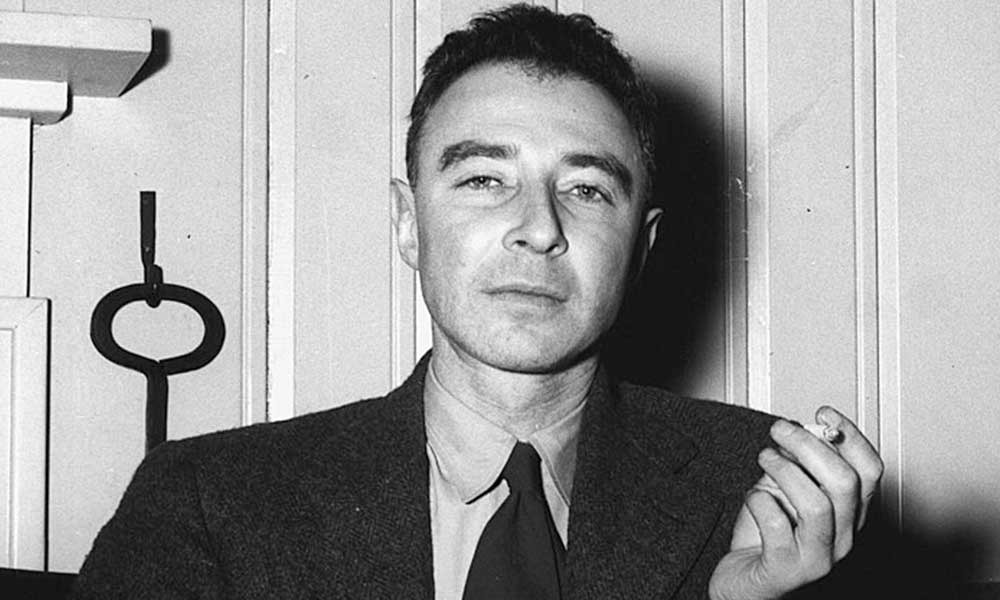

Oppenheimer made some seminal contributions in quantum mechanics and in black hole physics. He brought ‘quantum physics to the US’. However, Oppenheimer was also a public intellectual, who dabbled with left wing politics in his younger days. He rose to national prominence after he led Los Alamos National Laboratory as Director, in an effort that saw the US develop and wield nuclear weapons. He forever became known as the ‘father of the atom bomb’, a label that didn’t do anything to stop him spiraling into depression, as he saw his legacy tainted with death and destruction.

Nolan’s movie was a biopic, based on authors Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird’s Pulitzer Prize winning biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

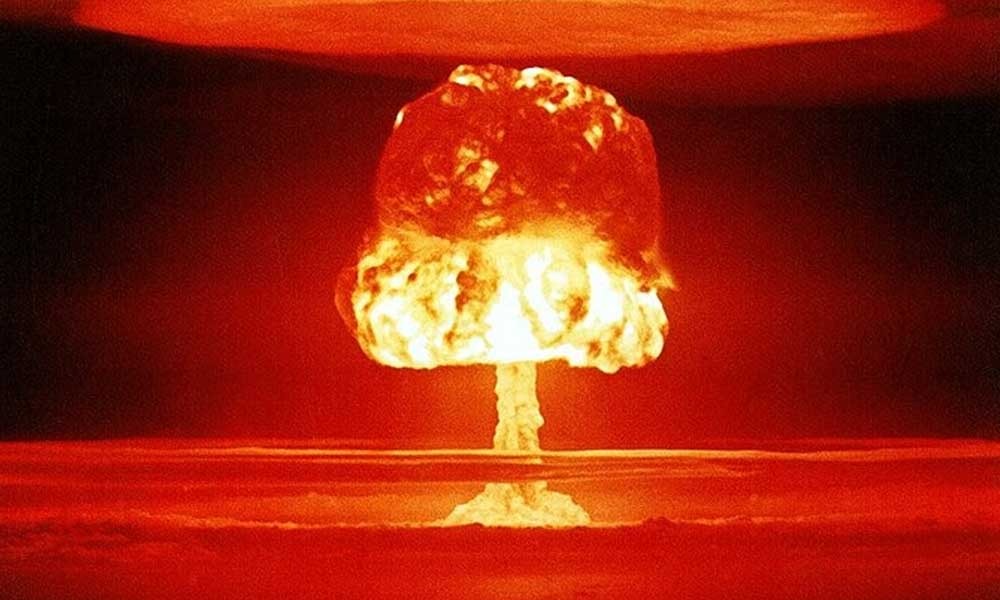

In a scene that shakes you to the core, Oppenheimer (played by Cilian Murphy) imagines seeing the horrific effects of a nuclear bombing on humans. A corpse flash fried, that crumbles upon the lightest touch. People mourning deaths of their loved ones, people vaporized leaving no traces behind. Others left alive with burns, and others vomiting irrecoverably from radiation sickness. Just imagine this is a time when people didn’t even really know what radiation sickness was all about. How many people would’ve dabbled with radioactivity? And now all it takes is one bomb to exact such a devastating toll on human life.

We wonder – who’s accountable for all this? The maker or the master? Or both?

Image of the nuclear detonation in US’ Castle Romeo test in 1954. Credit: United States Department of Energy

Oppenheimer lends an opportunity to assess scientists by holding them at the same pedestal as we do with politicians – especially when they’re prone to serious misjudgment. Oppenheimer thought the best way to demonstrate deterrence was to demonstrate the weapon’s capability. He assumed it wouldn’t proliferate, if they were demonstrated with an attack. ‘They (people) won’t fear it, unless they understand it, and they won’t understand it, until they’ve used it,’ as Cilian Murphy said in the movie. And they did use it.

Did people fear it? Yes and no. On one end there’s the physical damage of it all. But on the other end there came the political chain reaction – with nuclear arsenal stockpiling to record highs during the Cold War. There are still enough nukes around the world to end human civilization many times over.

Frankenstein died, but the monster lives on.

It’s an age-old claim now, as old as the Trinity test itself that it was impossible to stop the nuclear bomb developments. Somebody else or the other would have made it. This is sadly true. However, when we think of science itself – as Isidor Rabbi in the movie (played by David Krumholtz) said, ‘I don’t wish the culmination of three centuries of physics to be a weapon of mass destruction.’ Is science really divorced from political realities? Sure, a nuclear chain reaction isn’t dependent on policy. Of course, but launching an initiative to trigger one surely is. Leo Szilard’s letter sent to US President Theodore Roosevelt, signed off by Albert Einstein, discussed the feasibility of the US wielding a nuclear weapon to deter the Germans. That’s as straightforward as it can get.

It reflects policy change, when Nobel Peace Prize winner and nuclear physicist, Joseph Rotblat claimed General Leslie Groves (who oversaw the Manhattan Project) stating that it was the Soviets who the US seeked to intimidate with the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks. And when the Soviets surprised the US by revealing their own sophisticated nuclear program with a growing arsenal, the world locked up in a race for their own weapons. There was a total snafu.

Although Nolan used Sherwin and Bird’s source material as the inspiration for Oppenheimer to be depicted as a Prometheus, he’s also undoubtedly similar to Frankenstein as well.

Frankenstein died, but the monster lives on. What can we learn from all of this? Well, science and society are so intertwined that they both shape each other. The other is we may need to figure out who’s accountable for technological and scientific innovations.

Innovation may not really be unstoppable, if there’s collective action and we decide for ourselves what the world ought to be. Perhaps nuclear holocaust isn’t fictional, but at least we can do something for innovations in our society today.

“I have been interested to talk to some of the leading researchers in the AI field, and hear from them that they view this as their ‘Oppenheimer moment’,” said Nolan in an interview to The Guardian. AI can provide jobs as much as it takes away them, and that’s the challenge of our times. “And they’re clearly looking to his story for some kind of guidance … as a cautionary tale in terms of what it says about the responsibility of somebody who’s putting this technology to the world, and what their responsibilities would be in terms of unintended consequences.”

We’d rather be wise and learn from history, than repeat it. May that lead to an era of responsible innovation.

Sustainable Energy

India’s EV Investment Story: Rs 2.23 Lakh Crore Deployed, But 82% of Capital Needs Still Unmet

India’s charger-to-EV ratio continues to lag far behind global benchmarks—a structural weakness that could slow consumer adoption.

India’s electric mobility transition has entered a decisive yet challenging phase. A new analysis from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) reveals a complex narrative: while the country’s EV sector has attracted an impressive Rs 2.23 lakh crore in investments between 2020 and 2025, this represents just 18% of what India must mobilise by 2030 to meet its ambitious clean transport goals.

Unfolding against the backdrop of India’s expanding climate commitments and rising consumer interest in EVs, the report offers a data-rich look into where capital is flowing, where it is missing, and what structural challenges remain hidden beneath headline growth.

A Five-Year Surge in Capital—But Not Enough

Between 2020 and 2025, the EV ecosystem—spanning manufacturing facilities, public subsidies, and charging networks—absorbed Rs 2,23,119 crore in funding. This includes:

- Manufacturing investments supported primarily through internal accruals

- Government subsidies, especially through FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles)

- Charging infrastructure, which remains under-capitalised

Despite this influx, India’s 2030 targets—30% of private cars, 70% of commercial vehicles, 40% of buses, and 80% of two- and three-wheelers going electric—require a total of Rs12.5 lakh crore in investments. That leaves Rs 10.26 lakh crore still unmet.

“While Rs 2.23 lakh crore is a significant capital mobilisation in just five years, it represents only about 18% of the Rs12,50,000 crore required by 2030,” says co-author Subham Shrivastava. “Mobilising the remaining INR10,26,881 crore (USD117.82 billion) by 2030 will require systemic financing reforms.”

The Anatomy of EV Capital

A closer look at the numbers reveals how India’s EV push has been financed so far.

Internal reserves dominate

Manufacturers contributed the bulk of realised investment through their own internal accruals—Rs1,59,701 crore. Debt followed at Rs36,738 crore, while equity accounted for Rs 6,455 crore. But these aggregates obscure important differences across vehicle types.

The three-wheeler segment, driven by a fragmented OEM landscape and low capital-intensity operations, leaned heavily on internal funding and limited debt. Meanwhile, two- and four-wheeler categories showed more diverse capital structures due to the presence of established players and higher investment requirements.

“From 2020–2025, electric three-wheelers attracted the largest share (~78%) of investments among vehicle segments, due to the segment’s maturity and commercial-scale operations alongside its fragmented OEM base,” explains co-author Saurabh Trivedi. “However, recent investment announcements in 2024 and 2025 reveal a pivot towards electric four-wheelers, driven by rising demand for electric cars.”

Charging Infrastructure: A Massive Funding Gap

Perhaps the most critical bottleneck in India’s EV story is the underdeveloped charging ecosystem.

From 2020 to 2025, investments in public charging constituted just 9.6% of the ₹20,600 crore estimated need for 2030. While the country expanded its public chargers from 5,151 to 39,485 over five years, utilisation rates remain low and profitability uncertain.

“Investment in EV charging faces challenges due to limited investor interest, as public EV charging remains an unproven business model, with many charging stations reporting low utilisation rates and high initial costs,” notes co-author Charith Konda.

India’s charger-to-EV ratio continues to lag far behind global benchmarks—a structural weakness that could slow consumer adoption.

The Silent Brake on India’s EV Growth

Beyond infrastructure, the economics of financing EVs present another hurdle.

Commercial EV borrowers currently face interest rates of 15–33%, levels that wipe out the total cost-of-ownership advantage EVs typically offer.

“The binding constraint is not a lack of capital in the system—it is how EV risk is priced,” Shrivastava says. “When lenders remain uncertain about battery performance, residual values, and cash-flow stability, that uncertainty gets reflected in higher interest rates.”

High financing costs disincentivise fleet operators and businesses from transitioning to EVs. As a result, manufacturing capacity cannot scale at the pace needed, creating a demand-supply mismatch.

A New Model for Mobilising Capital

To unlock the remaining ₹10.3 lakh crore needed over the next five years, IEEFA proposes a shift away from subsidy-led growth toward structural risk-sharing.

The solution: a coordinated integrated EV financing platform that consolidates:

- Partial credit guarantees

- Residual value protection for batteries

- Battery-as-a-service (BaaS) arrangements

- Co-lending structures

This platform would be anchored by development finance institutions with relevant expertise—SIDBI for MSMEs and small commercial fleets, and IIFCL for large commercial deployments.

“Manufacturers need predictable demand signals to scale capacity, but demand depends heavily on affordable credit,” Trivedi adds. “An integrated platform that shares risks appropriately across lenders, OEMs, and public institutions can reduce financing costs and unlock commercial-scale deployment.”

The idea is that as EV adoption grows and asset performance data becomes more robust, lenders will recalibrate risk premiums downward. Over time, underwriting practices could standardise, securitisation markets may emerge, and capital could recycle more efficiently.

A Self-Reinforcing Investment Loop

The report outlines a possible virtuous cycle:

- Lower financing costs stimulate EV adoption

- Higher sales volumes create better performance data

- Improved visibility reduces risk perception

- Lower risk draws in more capital

- Manufacturers scale up, benefiting from economies of scale

- Reduced costs further accelerate adoption

This dynamic, according to IEEFA, is essential for unlocking a mature and self-sustaining EV ecosystem.

A Race Between Ambition and Capital

India’s electric transport ambitions are clear and achievable—but only if the investment framework evolves as rapidly as consumer interest and technological capability.

The core message from the data is unmistakable: India is moving in the right direction, but far too slowly. Recognising this, the authors warn that the next five years will determine the trajectory of India’s EV revolution. The country must transition from policy-driven electrification to a financially self-sustaining ecosystem capable of attracting large volumes of private capital at scale.

The question is no longer about policy commitment but about the cost, structure, and flow of capital in an evolving, high-potential sector.

Climate

More Shade for the Rich: Study Exposes Global Urban Heat Inequality

New MIT research shows how wealthier neighbourhoods enjoy more tree shade, exposing global heat inequality and offering solutions for fairer urban cooling.

As extreme heat becomes a growing global concern, one of the most effective cooling tools remains remarkably simple: trees. Research has long shown that greater tree coverage in cities helps reduce surface temperatures, improve public health outcomes, and make walking more comfortable in high heat.

Yet a new international study led by researchers at MIT reveals that access to this natural relief is far from equal. Tree cover — and the shade it provides — varies drastically within cities, closely tracking neighborhood wealth.

“Shade is the easiest way to counter warm weather,” said Fabio Duarte, an MIT urban studies scholar and co-author of the study, in a media statement. “Strictly by looking at which areas are shaded, we can tell where rich people and poor people live.”

The research team analyzed sidewalk shade in nine cities across four continents: Amsterdam, Barcelona, Belem, Boston, Hong Kong, Milan, Rio de Janeiro, Stockholm, and Sydney. Despite major differences in climate, wealth, and urban form, every city showed the same trend: affluent areas consistently enjoy more tree-shaded sidewalks.

Duarte noted that this imbalance was striking even in cities globally recognized for greenery. “When we compare the most well-shaded city in our study, Stockholm, with the worst-shaded, Belem in northern Brazil, we still see marked inequality,” he said in a media statement. “Even though the most-shaded parts of Belem are less shaded than the least-shaded parts of Stockholm, shade inequality in Stockholm is greater. Rich people in Stockholm have much better shade provision as pedestrians than we see in poor areas of Stockholm.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications, in a paper titled Global patterns of pedestrian shade inequality. The research team includes scholars from Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions, and members of the MIT Senseable City Lab.

A Global Look at Uneven Shade

To quantify shade, the team used satellite imagery and detailed urban economic data to measure sidewalk coverage on both the summer solstice and the hottest day each year from 1991 to 2020. They assigned each neighbourhood a score between 0 and 1, with higher numbers indicating better shade.

Cities differed sharply in total tree cover — for instance, Stockholm’s neighbourhoods often score above 0.6, while large portions of Rio de Janeiro fall below 0.1. But the inequality within each city was consistent: the wealthiest neighbourhoods always had the greatest shade.

Even in cities known for strong environmental planning, disparities remained. “In rich cities like Amsterdam, even though it’s relatively well-shaded, the disparity is still very high,” said Lukas Beuster, a study co-author. “For us the most surprising point was not that in poor cities and more unequal societies the disparity would be notable — that was expected. What was unexpected was how the disparity still happens and is sometimes more pronounced in rich countries.”

Not all trends were uniform. Some cities, such as Barcelona and Milan, featured lower-income neighborhoods with strong shade coverage. Still, across the global sample, economic status remained a powerful indicator of access to cool, walkable streets.

Why Shade Matters — and What Cities Can Do

Sidewalks became the focal point of the study because they are crucial public spaces used daily by commuters, especially those without access to air conditioning or private vehicles. As cities worldwide face rising temperatures, researchers argue that shade must be treated as essential infrastructure.

“When it comes to those who are not protected by air conditioning, they are also using the city, walking, taking buses, and anybody who takes a bus is walking or biking to or from bus stops,” Duarte explained in a communication from MIT. “They are using sidewalks as the main infrastructure.”

Given the scale of disparity, the researchers suggest one clear strategy: target tree planting along public transit routes, where pedestrian activity is highest and where lower-income residents are most likely to walk.

“In each city, from Sydney to Rio to Amsterdam, there are people who, regardless of the weather, need to walk,” Duarte said . “Therefore, link a tree-planting scheme to a public transportation network. … If you follow transit, you will have the right shading.”

Beuster added that cities should think of urban trees as functional assets, not just aesthetic ones, emphasizing their central role in cooling and public health.

Duarte further stressed the importance of prioritizing shade where people actually move through the city. “It’s not just about planting trees,” he said in a media statement. “It’s about providing shade by planting trees. If you remove a tree that’s providing shade in a pedestrian area and you plant two other trees in a park, you are still removing part of the public function of the tree.”

“With increasing temperatures, providing shade is an essential public amenity,” he added in a media statement. “Along with providing transportation, I think providing shade in pedestrian spaces should almost be a public right.”

Climate

IEA Ministerial 2026: Global Energy Leaders Expand Ties, Push Critical Minerals Security

At the IEA Ministerial Meeting in Paris, 54 countries backed expanded membership talks with Brazil, India, Colombia and Viet Nam, while strengthening cooperation on critical minerals and clean energy security.

Global energy leaders convened in Paris this week for the International Energy Agency’s Ministerial Meeting, underscoring the agency’s expanding role in shaping international cooperation at a time of rising demand, geopolitical tensions, and accelerating energy transitions.

The two-day gathering drew senior government representatives from a record 54 countries, around 40 of them at ministerial level. Executives from 55 companies — representing a combined market capitalisation of $14 trillion — joined leaders of intergovernmental organisations in what became the largest Ministerial Meeting in the agency’s history.

At the heart of the discussions was a clear message: energy security, affordability and sustainability can no longer be pursued in isolation. They require deeper multilateral coordination, stronger data systems, and expanded institutional alliances.

Expanding the IEA Family

Member governments unanimously agreed to move forward on strengthening institutional ties with Brazil, Colombia, India and Viet Nam. In a major step, Colombia was invited to become the IEA’s 33rd Member. Brazil was invited to begin the process toward full membership following a request from its government. Ministers also welcomed recent progress in discussions with India regarding its request for full membership. Viet Nam joined as the newest Association country in the IEA Family.

The expansion significantly alters the geometry of global energy governance. With these additions, the IEA Family’s share of global energy consumption now exceeds 80%, up from less than 40% a decade ago — reflecting a profound shift in the agency’s global reach.

“This Ministerial Meeting, our largest ever, affirmed the immense value of the IEA at a moment when global energy demand is rising and the challenges facing the energy system are intensifying. In this context, our wide range of objective data and analysis is more important than ever,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol.

“In a strong step forward for global energy governance, key countries such as Brazil, Colombia, India and Viet Nam are strengthening their ties with the IEA. This puts the IEA Family’s share of global energy use at more than 80%, up from less than 40% ten years ago. With major energy issues high on the international agenda, we stand ready to support governments with the insights they need to plan for the future, helping leaders deliver on their goals of ensuring greater energy security, affordability and sustainability.”

Deputy Prime Minister Sophie Hermans of the Netherlands, who chaired the Ministerial, framed the discussions in terms of resilience amid uncertainty.

“These two days in Paris have reaffirmed how essential energy is to our daily lives – it is the invisible driving force behind everything we do. Under the umbrella of knowledge of the International Energy Agency, we have once again seen that international cooperation is key,” she said. “Our priority is clear: secure, affordable and sustainable energy – and resilient systems that can endure in an uncertain world.”

In a video address opening the meeting, French President Emmanuel Macron emphasised the IEA’s analytical leadership. “Through its in-depth analyses, and the technical expertise of its team, the IEA, under the leadership of its Executive Director Fatih Birol, plays an essential role. It enlightens us to help us guarantee our energy security and steer the energy transition.”

Beyond institutional expansion, the Ministerial marked a strong endorsement of deeper cooperation on critical minerals — increasingly viewed as the backbone of clean energy technologies.

In a special declaration, Ministers backed expanding collaboration under the IEA Critical Minerals Security Programme to address mounting risks to global supply chains. They called for strengthened data tools, collaborative exercises and clearer guidance on measures such as stockpiling, aimed at diversifying supply chains and building resilience against supply shocks.

Clean Cooking and Energy Access

Member countries also approved the integration of the Clean Cooking Alliance into the IEA, positioning the agency as the principal multilateral forum for advancing clean cooking solutions. The move seeks to accelerate access for the more than two billion people worldwide who still lack clean cooking technologies.

The integration comes ahead of the IEA’s second Summit on Clean Cooking in Africa, scheduled for July 2026 in Nairobi, where governments and industry leaders are expected to review progress since the inaugural 2024 summit and outline new financing and policy pathways.

Energy Security in the Age of Electricity

Two high-level dialogues during the Ministerial focused on safeguarding energy security in what officials termed the “Age of Electricity,” and on supporting Ukraine’s energy system amid ongoing disruptions. Ukrainian First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Energy Denys Shmyhal participated in discussions on rebuilding and securing Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

As energy demand continues to climb and transition pathways grow more complex, the IEA’s expanding membership and programme scope suggest that multilateral coordination — once largely confined to oil security — is now being repositioned as the backbone of a rapidly electrifying and mineral-intensive global energy system.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet