COP30

COP30: How People, Not Politics, Are Powering the Next Phase of Climate Action

From rooftop revolutions to billion-dollar clean-energy investments, the global shift toward renewables is already happening — citizens and markets are leading where politics still hesitates.

As the world converges on Belém for the 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30), the air is heavy not just with Amazonian humidity—but with expectation. Ten years after the Paris Agreement, the story of global climate action has entered a new chapter. One defined less by negotiation rooms and more by rooftops, communities, and citizens who have already begun to build the future politicians still debate.

A new statement released just a week before the summit, titled “Protect What We Love,” captures this shift. Signed by 75 leaders across politics, culture, and civil society—including Christiana Figueres, Ban Ki-Moon, Mary Robinson, Richard Branson, Stella McCartney, and Dia Mirza—the call to action urges governments to finally transform past commitments into tangible plans.

“You agreed to transition away from fossil fuels. You agreed to halt and reverse deforestation. You agreed to mobilize finance for adaptation and mitigation in developing countries,” the statement reminds world leaders. “At COP30, we ask you to show us how—through concrete plans and timelines—so that we can protect the people and places we love.”

This appeal comes amid fresh global polling data showing what the authors call “the 89%”—an overwhelming majority of citizens worldwide who want faster climate action. The findings, by the Potential Energy Coalition, reveal that eight in ten people across ten countries support government investment in wind, solar, and nuclear energy—double the number backing fossil fuels. And notably, that support transcends politics. Even conservatives, often framed as skeptics, are 1.6 times more likely to favour clean-energy investment than fossil fuel subsidies.

A Decade That Defied Predictions

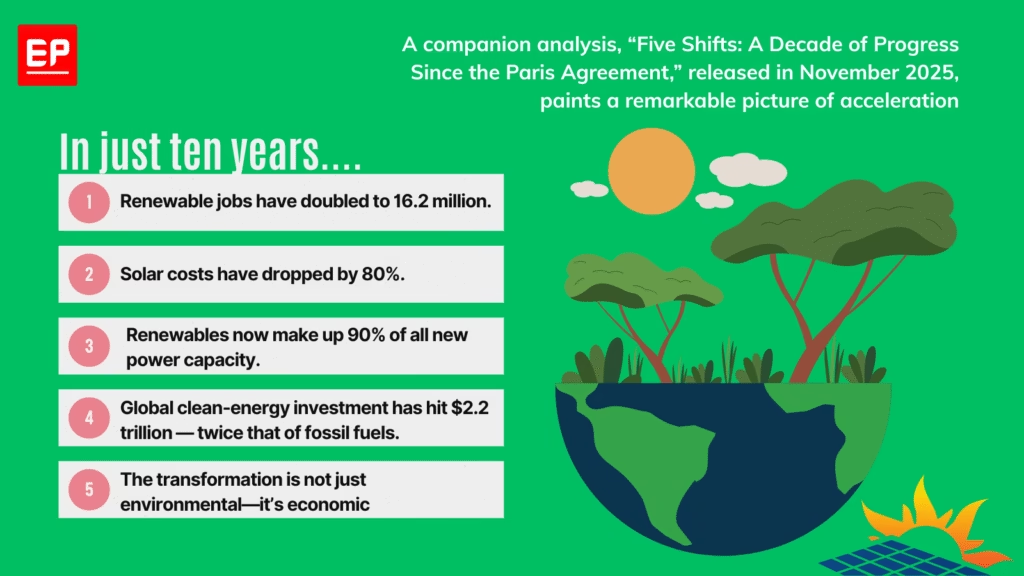

That popular consensus coincides with new evidence of real progress. According to “Five Shifts: A Decade of Progress Since the Paris Agreement,” released in early November 2025, the world has made more headway in clean-energy deployment and policy integration than most experts dared to expect back in 2015.

In the decade since Paris, renewable energy jobs have nearly doubled to 16.2 million, and annual clean-energy investments reached $2.2 trillion—twice that of fossil fuels. Ninety percent of all new power capacity added globally in 2025 came from renewables. Solar costs have plummeted by 80% since 2014.

The transformation is not just environmental—it’s economic. “The fossil fuel industry knows that the new economy is rising,” said Christiana Figueres, one of the architects of the Paris Agreement. “They know that they can no longer compete. We are no longer in a world in which only climate politics has a leading role, but increasingly climate economics.”

That’s a profound shift in the centre of gravity. In 2015, climate action depended on international consensus. In 2025, it increasingly depends on investment logic.

From Pledges to Proof

Still, COP30 will test whether politics can keep pace with the real world. “It’s a different kind of COP than we’ve had before,” said Jennifer Morgan, Germany’s Special Envoy for International Climate Action. “It is one where there’s not one big fund or one big outcome. One really needs to be looking at the signals, the decisions, and the proof points to see how leaders and countries are accelerating implementation—because that’s what this is all about: going faster, going further, building on the success, learning the lessons of the lack of success.”

The Five Shifts report echoes that sentiment. Its authors warn that while clean energy is winning both economically and politically, emissions are not yet falling at the speed required. The UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2025, published days before the summit, estimates that even with full implementation of current national climate plans (NDCs), global warming would reach 2.3–2.5°C, and 2.8°C under existing policies.

$2.2 trillion in clean-energy investment in 2025 — twice fossil fuels

The world is already 1.35°C warmer, with extreme heat events multiplying by a factor of nine since 2015. Yet the same report highlights practical successes: half of all countries now have heat-warning systems, and 47 operate national heat action plans, saving lives in cities from Senegal to Japan.

For Bill Hare, CEO of Climate Analytics, the takeaway is simple: “The world can still return to well below 1.5°C if the highest possible ambition is pursued by countries starting now. Getting to net zero carbon dioxide emissions means that we can halt warming pretty quickly.”

Citizens Are the New Climate Majority

What distinguishes COP30 from the summits before it is not just scientific urgency—it’s civic clarity. As the Protect What We Love statement declares, “We are the 89%: the overwhelming majority of the global population who want you to act faster on climate change.”

That human dimension is front and centre. Leanne Brummell, representing Parents for Future Global, spoke for millions of families when she said:

“As parents, our first duty is to protect our children. The climate crisis is a direct threat to their safety and their future… We are part of the 89% of people globally who want to see their governments take more action to protect the places and people we love.”

The emotional urgency resonates far beyond activist circles. Dia Mirza, actor and UN advocate, said: “As a mother, I see the truth of today’s statement in my children’s eyes every day. People everywhere are rising to build, buy, and create the solutions that will keep our children safe. Public support for climate action is undeniable, and the technology and answers already exist. At COP30, I ask world leaders to act with the same instinct every parent has—to protect what we love most: our children and their future.”

This groundswell of public will is now being matched by business leadership. A new E3G poll found 97% of global executives backing a rapid transition to renewable-based electricity. Major corporations have joined the We Mean Business coalition, urging governments to create policies that reward decarbonization rather than delay it.

“Climate breakdown is no longer a distant risk for business—it’s already disrupting operations through extreme weather events such as floods and droughts,” said Fiona Duggan, Global Sustainability Manager at Unilever. “Forward-thinking companies are moving to adapt and decarbonise as rapidly as their sectors will allow. The real question is whether governments will support them to go further, faster.”

Constructive Pathways: What’s Working

A decade of experimentation has produced more success stories than cynics expected. Countries once seen as dependent on fossil fuels—Nigeria, Senegal, Brazil, Indonesia—are embedding climate action into fiscal and planning systems. Nigeria’s 2021 Climate Law supports a 2060 net-zero target; Senegal’s local experts now drive national adaptation plans; Brazil’s Finance Ministry leads an Ecological Transformation Plan linking fiscal reform with green growth.

According to Henri Waisman, Director of the DDP Initiative, “Countries have begun to reshape climate governance, embed long-term perspectives into policymaking, and accelerate technological change. This progress is significant. But the lesson of the past decade is equally clear: if we are to achieve the goals of Paris, the next decade must be about scaling up efforts, addressing social and industrial challenges, and ensuring that ambition is consistently translated into effective action.”

These local models, backed by citizens’ trust and economic dividends, suggest that climate action isn’t just a moral imperative—it’s a viable development strategy.

The Belém Moment

If there’s a unifying message emerging from Rio’s press releases to Belém’s plenary halls, it’s this: the transition has already begun.

Citizens, investors, and innovators are not waiting for permission. “Ordinary people understand that clean energy will improve their lives and have begun the transition their leaders keep promising,” said environmentalist Bill McKibben. “Rooftop by rooftop, community by community, they’re proving the future can arrive before the politics to govern it.”

COP30 thus becomes less about what to agree upon—and more about how fast to deliver what’s already agreed. The Five Shifts report puts it succinctly: “COP30 must move beyond pledges to concrete delivery: addressing the ambition gap in current NDCs, accelerating finance for adaptation, and ensuring just transitions away from fossil fuels. The decisions made in Belém will determine whether the 2030s become a decade of decisive implementation.”

From Political Will to Public Proof

Ten years ago, in Paris, climate ambition was an act of collective imagination. In Belém, it’s a lived reality, visible in data, rooftops, and balance sheets. The clean-energy revolution is no longer hypothetical—it’s happening.

The challenge now is whether governments will catch up with their citizens. Because, as the 89% have made clear, the mandate to act isn’t waiting for another conference. It’s already out there—building, investing, and protecting what we love.

COP30

Greenwashing at Scale: How Big Oil Flooded Brazil With Ads Ahead of COP30

A global investigation reveals a 2,900% spike in oil-funded Google ads targeting Brazil, exposing a sophisticated digital greenwashing campaign designed to shape public opinion before COP30.

As COP30 concluded in Belém, a new report details how Big Oil used the months leading up to the summit to launch a massive digital greenwashing push across Brazil, one of the largest offensives seen in recent years. A new investigation reveals that major oil companies increased their Google ads targeting Brazil by an astonishing 2,900%, flooding search results with “clean energy” narratives designed to obscure their fossil-heavy expansion plans.

The report, A 2,900% Increase in Greenwash, released by the Climate Action Against Disinformation coalition (CAAD) and the Climainfo Institute, exposes how the world’s largest oil firms strategically poured money into Google’s advertising ecosystem between January and October 2025, with ad volumes peaking as Brazil’s COP30 preparations intensified and public debate around climate ambition surged.

The findings paint a stark picture, while oil companies publicly marketed themselves as climate allies, behind the scenes they executed a high-intensity digital influence operation aimed at shaping climate perceptions in the very country responsible for convening the next global climate negotiations.

“Every year Big Oil spends big money on greenwashing and disinformation to justify the pollution that’s killing people and the planet,” said Renata Albuquerque Ribeiro, a researcher at Climainfo, in a media statement. “This year, the scale went off the charts.”

“The scale of this advertising blitz is unprecedented and timed with precision to coincide with Brazil’s central role in global climate diplomacy,” said campaigners in a media statement accompanying the report.

“Every year Big Oil spends big money on greenwashing and disinformation, and it’s well past time policymakers stop letting Big Tech players like Google get rich off lies used to justify the pollution that’s killing people and the planet,” said CAAD coalition communications co-chair Philip Newell.

Brazil: A New Frontline in Fossil-Fuel Influence

Brazil’s selection as COP30 host has transformed the country into a strategic communication battleground. With the Amazon at the centre of global climate politics, Brazil’s diplomatic leadership poses a reputational challenge for oil giants that continue expanding fossil-fuel investments.

This context, researchers say, made Brazil a prime target for polished, tech-enabled influence campaigns.

Between January and October 2025:

- Oil companies purchased thousands of Google ads promoting “clean energy transitions,” “carbon-neutral futures,” and “sustainable innovation.”

- Ads surged most sharply in August–September, aligning with Brazil’s COP30 diplomatic roadmap announcements.

- Search terms related to “Brazil energy transition,” “climate leadership,” and “COP30 sustainability” were among the most heavily targeted.

Behind the glossy messaging, however, the report finds “systematic attempts to rebrand fossil expansion as climate progress” — a redirection strategy designed to nudge public sentiment in a country now shaping the agenda for global climate action.

2,900%: A Number That Signals Intent

A spike of nearly 30-fold in advertising is not organic. It is strategic.

Campaign researchers show that:

- In early 2025, oil companies ran almost no Google ads targeted specifically at Brazil.

- By mid-2025, this changed dramatically as the COP30 calendar gained traction.

- By October, ad volumes had soared 2,900% above January baselines.

“This is not simply a PR campaign — it is an influence operation with global stakes,” said the report’s authors.

The ads consistently highlighted themes such as “net-zero commitments,” “innovation pathways,” and “green technologies,” despite independent assessments showing these companies are increasing oil and gas investments far faster than clean energy expenditure.

“Petrobras, Brazil’s state-owned oil company, responsible for 86% of the country’s oil incidents, ran 665 ads in the first 10 months of 2025,” the report states.

“Saudi Aramco accounted for the highest share of ads in October. TotalEnergies and ExxonMobil dramatically increased their presence in mid-year. BP’s ads peaked as COP30 planning intensified,” one section of the report notes.

The Anatomy of Digital Greenwashing

The investigation found that nearly all ads shared three unifying characteristics:

1. Promoting Fossil Expansion as ‘Energy Security’

Ads framed continued oil and gas development as essential for stability, echoing language oil companies now frequently use to justify new drilling projects.

2. Overstating Climate Efforts

Phrases such as “leading on climate” and “investing in a net-zero future” dominated messaging — despite internal plans showing the opposite.

3. Targeting ‘Climate-Aware’ Audiences

The ads were deployed in Portuguese and English, aimed at Brazil’s urban, digitally connected population who would be most engaged in COP30 discourse.

This hyper-targeted strategy, the report says, relied heavily on Google’s algorithmic ad capabilities, allowing companies to “embed green narratives directly into the search environments of millions of Brazilians.”

Global Climate Diplomacy Meets Big Tech Influence

The findings raise alarming questions about the role of digital platforms in shaping global climate negotiations.

“Allowing fossil-fuel producers to amplify misleading narratives before a critical UN summit undermines democratic climate debate,” campaigners said in a media statement.

Experts warn that COP30 — intended to accelerate global transitions away from fossil fuels — risks becoming a communications battlefield dominated by the industries most responsible for climate instability.

“We believe that greenwashing in adverts by fossil fuel companies poses a major threat to climate information integrity,” added Travis Coan of C3DS.

In past summits, oil and gas lobbyists have been present inside negotiation halls. But the digital ad surge in Brazil signals a shift: the battle for influence is increasingly happening online, long before diplomatic delegations arrive.

Why Brazil Was Targeted

The report outlines several reasons Brazil became the epicentre of Big Oil’s digital scrutiny:

- COP30 host status: Global attention is shifting to Brazil’s climate platform.

- Amazon factor: The Amazon is a symbol of climate urgency — a narrative oil firms seek to overshadow.

- Energy transition debate: Brazil’s growing renewable portfolio contrasts sharply with fossil expansion elsewhere.

- Emerging regulatory gaps: Brazil lacks strict digital transparency laws governing paid climate messaging.

These conditions provided oil companies with a fertile landscape to reposition themselves as climate partners while continuing to invest heavily in fossil extraction.

When Greenwashing Meets Algorithms

The report argues that digital greenwashing has evolved beyond traditional PR. Today, misleading narratives are: algorithmically amplified, micro-targeted, geographically tailored, optimized for search behaviours, and delivered at scale.

The risk, researchers warn, is not just misinformation — it is the embedding of climate narratives that subtly distort public understanding of energy pathways.

And unlike political advertising, corporate climate ads often escape regulatory scrutiny.

From Big Oil to Big Influence: The Policy Gap

Despite the scale of the ad surge, there are few global frameworks requiring companies to disclose their digital spending on climate messaging.

Campaigners argue this gap gives fossil-fuel giants a powerful informational weapon in shaping global climate discourse.

“This level of opaque influence must be urgently addressed — especially when it targets COP host countries,” the report notes.

The authors call for stronger digital ad transparency rules, mandatory disclosures of climate-related paid messaging, clear restrictions on misleading environmental claims, and accountability from tech platforms like Google ahead of global climate events.

The investigation concludes that unchecked digital greenwashing threatens to distort public dialogue as Brazil prepares is hosting one of the most consequential climate negotiations of the decade.

And with oil companies poised to continue expanding their ad budgets into 2026, researchers warn that COP30 may become “the most digitally influenced climate summit ever.”

COP30

From 6% to 16%: The Philippines Shows the World How Fast Climate Budgets Can Shift

In just four years, the Philippines has expanded its climate spending from PHP 282 billion to over PHP 1 trillion — one of the fastest fiscal shifts anywhere in the world.

Governments across the world are beginning to rethink the way national budgets are designed, moving away from traditional fiscal planning and toward systems that integrate climate considerations directly into spending decisions. A new comparative review of global green-budgeting practices reveals a trend that is gathering momentum: more countries are using their budgets as climate-governance tools. But the pace of progress varies sharply between advanced economies and emerging markets.

The Rise of Climate-Conscious Budgets

Countries such as France, Ireland, Mexico and the Philippines provide some of the clearest examples of how climate priorities are reshaping national expenditure. France has increased its identified climate-positive budget from €38.1 billion in 2021 to €42.6 billion in 2025, while Ireland expanded its environmental allocations from €2 billion (2020) to €7 billion (2025). Mexico’s transformation has been even more rapid: climate-related expenditures rose from MXN 70 billion (2021) to MXN 466 billion (2025) — a six-fold increase.

A Sudden Surge in the Philippines

Nowhere is the shift more dramatic than the Philippines. After embedding climate budget tagging across its ministries, the country’s climate budget expanded from PHP 282 billion in 2021 to more than PHP 1 trillion in 2025, raising its share of the national budget from 6% to 16%. The reform forced ministries to assess thousands of programmes through a climate lens, resulting in a shift toward resilient infrastructure, sustainable energy, water security, and climate-smart industries.

Advanced Economies Move Beyond Tagging

While emerging economies are scaling up climate allocations, advanced economies are integrating climate metrics deeper into fiscal systems. Canada’s “climate lens” requires greenhouse-gas and resilience assessments for major infrastructure projects before funding is approved. Norway links its annual budget to its Climate Change Act and long-term low-emission strategies. Germany uses sustainability indicators to guide fiscal decisions, embedding climate considerations into macroeconomic planning.

These tools go beyond transparency. They force ministries to justify public spending not only in economic terms, but in climate terms — shifting budgets from accounting documents to steering instruments.

Despite this momentum, the analysis notes a persistent gap: many countries stop at tagging climate-related expenditures without linking them to outcomes or performance indicators. Tagging improves transparency, but on its own does not change investment decisions. Without climate-based appraisal and monitoring, high-emission infrastructure can still slip through national budgets unchallenged.

The Financing Challenge

For lower-income countries, the largest barriers are financial. High capital costs, limited fiscal room, and weaker public financial management systems restrict the scale of green budgeting reforms. Even when climate spending rises, sustaining these increases requires integrating climate metrics into medium-term fiscal frameworks — something only a handful of emerging economies have attempted.

Innovations Show What’s Possible

Some models offer a blueprint. Indonesia’s climate-tagging system feeds directly into its sovereign green sukuk framework, giving investors clear visibility over the use of proceeds. This loop — tagging, reporting, financing — demonstrates how governments can leverage green budgeting to unlock larger pools of private capital.

Still in Progress

The report concludes that the next frontier for green budgeting is integration: linking budget tagging, climate-lens project appraisal, performance-based reporting, and climate-aligned fiscal strategies. Done together, these tools allow budgets to become climate-governance instruments capable of guiding national transitions.

But the pace remains uneven. Some countries are racing ahead, while others are taking incremental steps. What is clear, however, is that climate-aligned public finance is no longer optional. As climate impacts intensify, the alignment of the world’s budgets will determine who adapts — and who is left behind.

COP30

Clean Energy Push Could Halve Global Warming by 2040, New Analysis Shows

A new Climate Action Tracker analysis shows that tripling renewables, doubling energy efficiency and cutting methane could halve global warming by 2040

A rapid global shift to renewable energy, energy efficiency and methane cuts could halve the rate of global warming by 2040, dramatically altering the world’s climate trajectory, a new Climate Action Tracker (CAT) assessment finds.

The analysis shows that implementing the three core COP28 energy and methane goals—tripling renewable energy capacity, doubling energy efficiency improvements, and delivering steep methane cuts by 2030—would bring down projected warming from the current 2.6°C to 1.7°C by the end of the century.

Crucially, these actions would sharply slow near-term warming, reducing the pace of temperature rise by a third by 2035 and nearly half by 2040, compared to today’s rate of ~0.25°C per decade. This slowdown is critical not just for long-term climate goals but for immediate survival, the report stresses.

A Turning Point

The world is already struggling to cope with accelerating climate impacts. With ecosystems collapsing faster than species can adapt and communities facing worsening heatwaves, storms and crop failures, “catching up” on adaptation has become a global emergency.

CAT warns that under current policies, warming could continue rising throughout the century, leaving governments perpetually behind on adaptation planning. But halving the warming rate would give both people and ecosystems a fighting chance to adjust.

A 0.9°C Improvement in the Global Outlook

If all countries implement the three goals, the resulting emission cuts—14 GtCO₂e by 2030 and 18 GtCO₂e by 2035—would reduce expected warming this century by 0.9°C, one of the most significant improvements since the Paris Agreement.

“This is the single biggest step governments can take this decade, using goals they have already negotiated and agreed to,” the report notes.

Where the Reductions Come From

- Tripling renewables: ~40% of total emission reductions

- Doubling energy efficiency: ~40%

- Methane cuts: ~20%, but delivering disproportionate warming benefits due to methane’s strong short-term impact

Finance Is the Missing Link

The report underscores that technology is not the barrier—finance is. Many emerging economies cannot deploy renewables or upgrade grids at the necessary pace without scaled-up international support.

Still, the authors say the pathway is feasible and grounded in technologies already available at commercial scale.

While the world is almost certain to overshoot 1.5°C by the early 2030s, the duration and magnitude of that overshoot will determine future levels of loss and damage. Delivering the COP28 energy and methane goals, the report concludes, is the most powerful tool the world currently has to limit that overshoot and avoid runaway climate impacts.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet