Health

Oxidative Stress Linked to Development of Cancer, Cardiovascular Diseases: Study

This breakthrough could pave the way for new therapeutic approaches targeting oxidative stress, offering hope for the treatment of a wide range of diseases where antioxidant responses are vital.

A new study by researchers at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology (RGCB), Kerala, India, has revealed a crucial connection between mRNA processing and oxidative stress response, shedding light on a condition that plays a pivotal role in the development of various diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, neurological diseases, and diabetes, as well as aging. The research emphasizes the critical impact of oxidative stress, particularly in the heart, which contributes to several health conditions such as hypertension, heart failure, hypoxia, ischemia-reperfusion injury, atherosclerosis, and hypertrophy (excessive development of an organ or tissue).

The team of scientists at RGCB, led by Dr. Rakesh S. Laishram (Scientist), Dr. Feba Shaji, and Dr. Jamshaid Ali, discovered that during oxidative stress, when reactive oxidative species exceed the cell’s capacity to neutralize them, the production of antioxidant proteins is boosted. This is achieved by enhancing the fidelity of RNA processing, a mechanism that helps cells combat oxidative stress. The study, published in Redox Biology journal, uncovers this novel pathway in gene expression.

In the gene expression process, DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into proteins responsible for carrying out various cellular functions. Manipulations in these pathways—whether through DNA, RNA, or proteins—can alter gene expression depending on the cellular state. RNA processing, a key pathway controlling gene expression, involves the cleavage of RNA. Interestingly, this cleavage is not always precise, with multiple potential cleavage sites, a phenomenon known as cleavage heterogeneity.

“Controlling oxidative stress is crucial for maintaining cellular health and preventing human diseases. One key way cells regulate oxidative stress is by controlling gene expression through alterations in DNA, RNA, or proteins,” says Dr. Laishram, highlighting the importance of this research in understanding how cells respond to oxidative stress through imprecisions in RNA processing. “This underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting cleavage precision in RNA to mitigate oxidative stress and its associated pathologies.”

Dr. Chandrabhas Narayana, Director of RGCB, described it a significant contribution to understanding how antioxidants influence the pathogenesis and development of diseases.

While previous research had not fully elucidated the mechanism, regulation, or biological implications of cleavage imprecision, this study challenges the common perception that such imprecision is merely error-prone. Dr. Shaji and her team discovered that cleavage imprecision is tightly regulated, playing a critical role in controlling gene expression in response to oxidative stress. Key oxidative stress response genes, such as NQO1, HMOX1, PRDX1, and CAT, show higher heterogeneity compared to genes involved in non-stress responses. Furthermore, the number of cleavage sites on these RNA molecules is reduced, enabling cells to better respond to oxidative stresses.

The RGCB researchers have now shown that this heterogeneity is driven by a fidelity cleavage complex that cleaves RNA at a primary site during oxidative stress. This study marks the first example of the biological significance of cleavage imprecision, which regulates gene expression in the cellular oxidative stress response. The findings offer a novel mechanism of antioxidant response, distinct from other oxidative stress pathways, with far-reaching implications for understanding the pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular conditions, inflammation, neurodegeneration, aging, and diabetes.

This breakthrough could pave the way for new therapeutic approaches targeting oxidative stress, offering hope for the treatment of a wide range of diseases where antioxidant responses are vital.

Health

Study Unveils Mucus Molecules That Block Salmonella and Prevent Diarrhea

A new MIT-led study reveals how key mucus molecules naturally shield the gut from dangerous bacteria like Salmonella

A new MIT-led study reveals how key mucus molecules naturally shield the gut from dangerous bacteria like Salmonella. The breakthrough opens new pathways for affordable, preventative treatments for travelers and soldiers at risk of infection.

Researchers at MIT have discovered new powerful ways the body guards itself from dangerous bacteria: by deploying mucins, special molecules in mucus that neutralize microbes and stop infection before it starts. The team identified mucins—especially MUC2 and MUC5AC—in the digestive tract that shut down the genetic machinery Salmonella uses to invade cells and cause diarrhea.

“By using and reformatting this motif from the natural innate immune system, we hope to develop strategies to preventing diarrhea before it even starts. This approach could provide a low-cost solution to a major global health challenge that costs billions annually in lost productivity, health care expenses, and human suffering,” said Katharina Ribbeck, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor of Biological Engineering at MIT, in a media statement.

In experiments, exposing Salmonella to the intestinal mucin MUC2 blocked the bacterial proteins that enable infection, turning off the critical regulator HilD. The study also found that a similar mucin from the stomach, MUC5AC, works the same way—and both molecules appear to protect against multiple foodborne germs triggered by similar genetic switches.

“We discovered that these mucins not only create a physical shield but also actively control whether pathogens can turn on genes needed for infection,” Ribbeck explained in the media statement.

Lead authors Kelsey Wheeler and Michaela Gold say synthetic versions of these mucins could soon be added to oral rehydration salts or chewable tablets, providing practical protection for troops, travelers, and people in high-risk areas. According to Wheeler, “Mucin mimics would particularly shine as preventatives, because that’s how the body evolved mucus — as part of this innate immune system to prevent infection,” she said.

Health

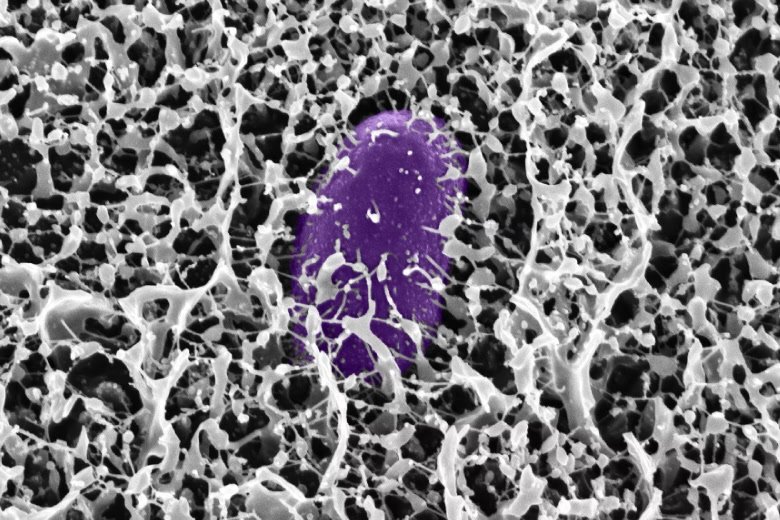

First Case of Rare and Deadly Fungus Identified in Sub-Saharan Africa

It is also the first time the rare and deadly fungal infection has been identified in an HIV-positive patient in the region

Doctors at the University of the Free State (UFS) and the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) at the Universitas Academic Hospital have confirmed the first recorded case of S. oblongispora mucormycosis in sub-Saharan Africa. It is also the first time the rare and deadly fungal infection has been identified in an HIV-positive patient in the region.

The case involved a 32-year-old man living with HIV who was admitted to Universitas Academic Hospital with severe swelling on the right side of his face. Despite being on antiretroviral therapy and treatment for hypertension, his condition worsened rapidly. Four days after admission, a CT scan and tissue biopsies were conducted. He died three days later, before a diagnosis could be confirmed.

Landmark discovery

Dr. Bonita van der Westhuizen, Senior Lecturer and Pathologist in the UFS Department of Medical Microbiology, described the discovery as a critical turning point for public health in the region.

“This discovery is significant because it highlights the presence of this fungal pathogen in a region where it may have been previously unrecognised or underreported. It now raises awareness about the diversity of fungal infections affecting immunocompromised populations and underscores the need for improved diagnostics, surveillance, and treatment strategies in the region,” she said in a media statement sent to EdPublica.

The case report, co-authored with Drs. Liska Budding and Christie Esterhuysen from the UFS/NHLS and Prof. Samantha Potgieter from the UFS Department of Internal Medicine, was published in Case Reports in Pathology last month.

Rapid and aggressive disease

Mucormycosis, caused by fungi from the order Mucorales, is known for its speed and severity. The infection can invade blood vessels, spread to vital organs, and resist the body’s immune defences.

“Mucorales fungi are known for their fast growth and ability to invade blood vessels. This allows the infection to spread quickly through the body, potentially reaching vital organs,” Dr. Van der Westhuizen explained in the statement. She added that external factors such as traumatic injuries or hospital-acquired infections can worsen the disease’s progression.

While mucormycosis usually strikes patients with underlying conditions like diabetes, cancer, or organ transplants, S. oblongispora has often been linked to infections in otherwise healthy individuals after traumatic inoculation. The lack of local data, however, means its prevalence in African populations remains unclear.

Diagnostic hurdles

In this case, invasive fungal infection was not initially suspected, and the patient did not receive antifungal medication or surgical treatment. The diagnosis was confirmed only after his death, highlighting the broader challenges of detecting fungal diseases in resource-limited settings.

“This is unfortunately the case with mould infections as most readily available diagnostic methods lack sensitivity and these pathogens take long to grow in the laboratory,” Dr. Van der Westhuizen said. “Fungal diagnostics is a specialised field that requires expertise. However, if clinicians are aware of these infections and they have an increased index of suspicion, appropriate therapy can be initiated even before the results are available.”

Experts warn that even with antifungal drugs and surgical removal of infected tissue, the window for treatment is narrow and survival rates remain low.

Building awareness and research

Dr. Van der Westhuizen is continuing her research on invasive mould infections as part of her PhD, focusing on fungal epidemiology and its impact on vulnerable groups such as HIV patients.

Her goal, she said in the media statement, is “to advance understanding and awareness of invasive mould infections, specifically S. oblongispora, in sub-Saharan Africa and among HIV patients. I aim to improve early diagnosis, treatment strategies, and clinical outcomes, as well as to highlight the importance of monitoring fungal infections in immunocompromised populations.”

She hopes the findings will spur more regional collaboration and investment in fungal diagnostics — an often overlooked but increasingly urgent frontier in infectious disease research.

Health

Giant Human Antibody Found to Act Like a Brace Against Bacterial Toxins

This synergistic bracing action gives IgM a unique advantage in neutralizing bacterial toxins that are exposed to mechanical forces inside the body

Our immune system’s largest antibody, IgM, has revealed a hidden superpower — it doesn’t just latch onto harmful microbes, it can also act like a brace, mechanically stabilizing bacterial toxins and stopping them from wreaking havoc inside our bodies.

A team of scientists from the S.N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences (SNBNCBS) in Kolkata, India, an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), made this discovery in a recent study. The team reports that IgM can mechanically stiffen bacterial proteins, preventing them from unfolding or losing shape under physical stress.

“This changes the way we think about antibodies,” the researchers said in a media statement. “Traditionally, antibodies are seen as chemical keys that unlock and disable pathogens. But we show they can also serve as mechanical engineers, altering the physical properties of proteins to protect human cells.”

Unlocking a new antibody role

Our immune system produces many different antibodies, each with a distinct function. IgM, the largest and one of the very first antibodies generated when our body detects an infection, has long been recognized for its front-line defense role. But until now, little was known about its ability to physically stabilize dangerous bacterial proteins.

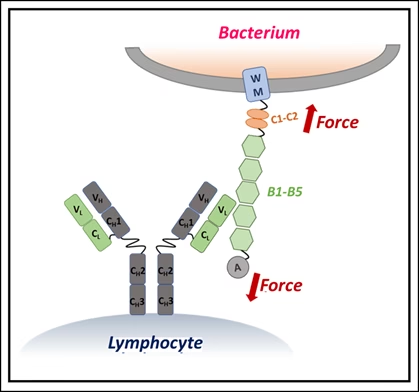

The SNBNCBS study focused on Protein L, a molecule produced by Finegoldia magna. This bacterium is generally harmless but can become pathogenic in certain situations. Protein L acts as a “superantigen,” binding to parts of antibodies in unusual ways and interfering with immune responses.

Using single-molecule force spectroscopy — a high-precision method that applies minuscule forces to individual molecules — the researchers discovered that when IgM binds Protein L, the bacterial protein becomes more resistant to mechanical stress. In effect, IgM braces the molecule, preventing it from unfolding under physiological forces, such as those exerted by blood flow or immune cell pressure.

Why size matters

The stabilizing effect depended on IgM concentration: more IgM meant stronger resistance. Simulations showed that this is because IgM’s large structure carries multiple binding sites, allowing it to clamp onto Protein L at several locations simultaneously. Smaller antibodies lack this kind of stabilizing network.

“This synergistic bracing action gives IgM a unique advantage in neutralizing bacterial toxins that are exposed to mechanical forces inside the body,” the researchers explained.

The finding highlights an overlooked dimension of how our immune system works — antibodies don’t merely bind chemically but can also act as mechanical modulators, physically disarming toxins.

Such insights could open a new frontier in drug development, where future therapies may involve engineering antibodies to stiffen harmful proteins, effectively locking them in a harmless state.

The study suggests that by harnessing this natural bracing mechanism, scientists may be able to design innovative treatments that go beyond traditional antibody functions.

-

Space & Physics5 months ago

Space & Physics5 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Earth6 months ago

Earth6 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoDid JWST detect “signs of life” in an alien planet?

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

-

Society6 months ago

Society6 months agoRabies, Bites, and Policy Gaps: One Woman’s Humane Fight for Kerala’s Stray Dogs