Space & Physics

In search for red aurorae in ancient Japan

Ryuho Kataoka, a Japanese auroral scientist, played a seminal role in searching for evidence of super-geomagnetic storms in the past using historical methods

Aurorae seen on Earth are the end of a complex process that begins with a violent, dynamic process deep within the sun’s interior.

However, studying the depths of the sun is no easy task, even for scientists. The best they can do is to observe the surface using space-based telescopes. One problem that scientists are attempting to solve is how a super-geomagnetic storm on Earth comes to being. These geomagnetic storms find their roots in sunspots, that are acne-like depressions on the sun’s surface. As the sun approaches the peak of its 11-year solar cycle, these sunspots, numbering in the hundreds, occasionally release all that stored magnetic energy into deep space, in the form of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) (which are hot wisps of gas superheated to thousands of degrees).

Super-geomagnetic storms, a particularly worse form of geomagnetic storm, can induce power surges in our infrastructure, causing power outages that can plunge the world into darkness, and can cause irreversible damages to our infrastructure

If the earth lies in the path of an oncoming CME, the energy release from their resultant magnetic field alignment can cause intense geomagnetic storms and aurorae on Earth.

This phenomenon, which is astrophysical and also electromagnetic in nature, can have serious repercussions for our modern technological society.

Super-geomagnetic storms, a particularly worse form of geomagnetic storm, can induce power surges in our infrastructure, causing power outages that can plunge the world into darkness, and can cause irreversible damages to our infrastructure. The last recorded super-geomagnetic storm event occurred more than 150 years ago. Known as the Carrington event, the storm destroyed telegraph lines across North America and Europe in 1859. The risk for a Carrington-class event to happen again was estimated to be 1 in 500-years, which is quite low, but based on limited data. Ramifications are extremely dangerous if it were to ever happen.

However, in the past decade, it was learnt that such super-geomagnetic storms are much more common than scientists had figured. To top it all, it wasn’t just science, but it was a valuable contribution by art – specifically ancient Japanese and Chinese historical records that shaped our modern understanding of super-geomagnetic storms.

Ryuho Kataoka, a Japanese space physicist, played a seminal role in searching for evidence of super-geomagnetic storms in the past using historical methods. He is presently an associate professor in physics, holding positions at Japan’s National Institute of Polar Research, and The Graduate University for Advanced Studies.

“There is no modern digital dataset to identify extreme space weather events, particularly super-geomagnetic storms,” said Professor Kataoka. “If you have good enough data, we can input them into supercomputers to do physics-based simulation.”

However, sunspot records go until the late 18th century when sunspots were actively being cataloged. In an effort to fill the data gap, Professor Kataoka decided to be at the helm of a very new but promising interdisciplinary field combining the arts with space physics. “The data is limited by at least 50 years,” said Professor Kataoka. “So we decided to search for these red vapor events in Japanese history, and see the occurrence patterns … and if we are lucky enough, we can see detailed features in these lights, pictures or drawings.” Until the summer of 2015, Ryuho Kataoka wasn’t aware of how vast ancient Japanese and Chinese history records really were.

“There is no modern digital dataset to identify extreme space weather events, particularly super-geomagnetic storms,” said Professor Kataoka.

In the past 7 years, he’s researched a very specific red aurora, in documents extending to more than 1400 years. “Usually, auroras are known for their green colors – but during the geomagnetic storm, the situation is very different,” he said. “Red is of course unusual, but we can only see red during a powerful geomagnetic storm, especially in lower latitudes. From a scientific perspective, it’s a very reasonable way to search for red signs in historical documents.”

A vast part of these historical red aurora studies that Professor Kataoka researched came from literature explored in the last decade by the AURORA-4D collaboration. “The project title included “4D”, because we wanted to access records dating back 400 years back during the Edo period,” said Professor Kataoka.

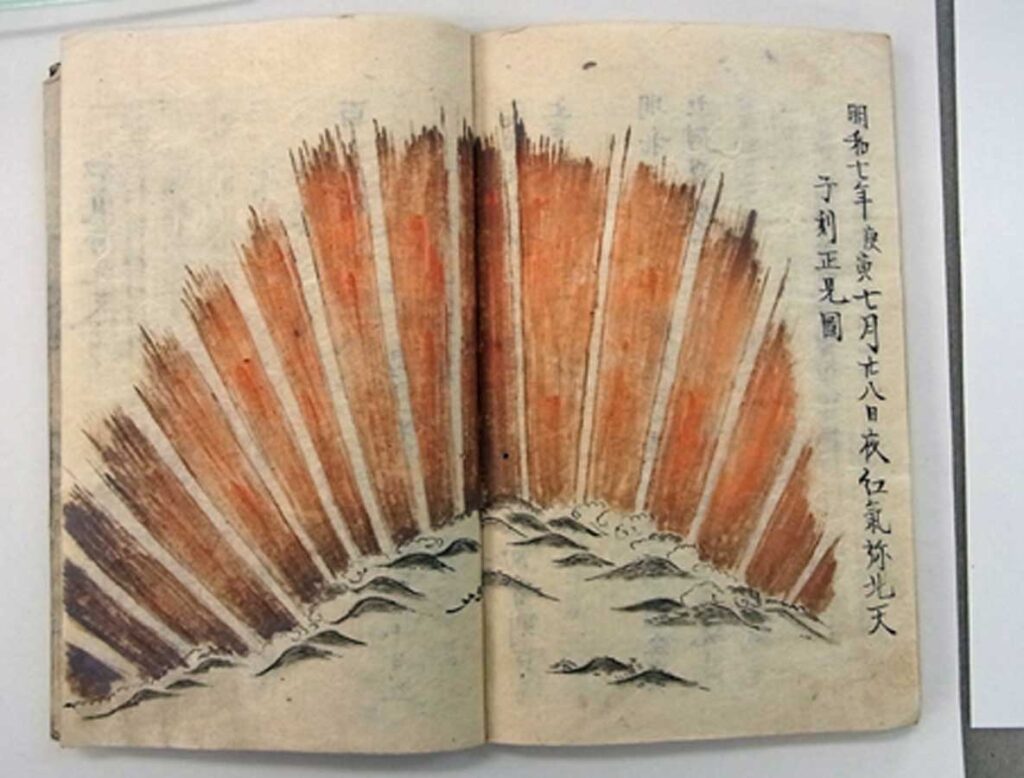

“From the paintings, we can identify the latitude of the aurora, and calculate the magnitude or amplitude of the geomagnetic storm.” Clearly, paintings in the Edo period influenced Professor Kataoka’s line of research, for a copy of the fan-shaped red aurora painting from the manuscript Seikai (which translates to ‘stars’) hangs on the window behind his office desk at the National Institute of Polar Research.

The painting fascinated Professor Kataoka, since it depicted an aurora that originated during a super-geomagnetic storm over Kyoto in 1770. However, the painting did surprise him at first, since he wondered whether the radial patterns in the painting were real, or a mere artistic touch to make it look fierier. “That painting was special because this was the most detailed painting preserved in Japan,” remarked Professor Kataoka. “I took two years to study this, thinking this appearance was silly as an aurorae scientist. But when I calculated the field pattern from Kyoto towards the North, it was actually correct!”

Fan-shaped red aurora painting from the ‘Seikai’, dated 17th September, 1770; Picture Courtesy: Matsusaka City, Mie Prefecture.

The possibility to examine and verify historical accounts using science is also a useful incentive for scholars of Japanese literature and scientists partaking in the research.

“This is important because, if we scientists look at the real National Treasure with our eyes, we really know these sightings recorded were real,” said Professor Kataoka. “The internet is really bad for a survey because it can easily be very fake,” he said laughing. It’s not just the nature in which science was used to examine art – to examine Japanese “national treasures” that is undoubtedly appealing, but historical accounts themselves have contributed to scientific research directly.

“From our studies, we can say that the Carrington class events are more frequent than we previously expected,” said Professor Kataoka. There was a sense of pride in him as he said this. “This Carrington event is not a 1 in 200-year event, but as frequent as 1 in 100 years.” Given how electricity is the lifeblood of the 21st century, these heightened odds do ingrain a rather dystopian society in the future, that is ravaged by a super-geomagnetic storm.

Professor Kataoka’s work has found attention within the space physics community. Jonathon Eastwood, Professor of Physics at Imperial College London said to EdPublica, “The idea to use historical information and art like this is very inventive because these events are so rare and so don’t exist as information in the standard scientific record.”

There’s no physical harm from a geomagnetic storm, but the threat to global power supply and electronics is being increasingly recognized by world governments. The UK, for instance, identified “space weather” as a natural hazard in its 2011 National Risk Register. In the years that followed, the government set up a space weather division in the Met Office, the UK’s foremost weather forecasting authority, to monitor and track occurrences of these coronal mass ejections. However, these forecasts, which often supplement American predictions – namely the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – have failed to specify previously where a magnetic storm could brew on Earth, or predict whether a coronal mass ejection would ever actually strike the Earth.

Professor Kataoka said he wishes space physicists from other countries participate in similar interdisciplinary collaborations to explore their native culture’s historical records for red aurora sightings

The former occurred during the evacuation process for Hurricane Irma in 2017, when amateur radio ham operators experienced the effects of a radio blackout when a magnetic storm affected the communications network across the Caribbean. The latter occurred on another occasion when a rocket launch for SpaceX’s Starlink communication satellites was disrupted by a mild geomagnetic storm, costing SpaceX a loss of over $40 million.

Professor Kataoka said he wishes space physicists from other countries participate in similar interdisciplinary collaborations to explore their native culture’s historical records for red aurora sightings. He said the greatest limitation of the AURORA-4D collaboration was the lack of historical records from other parts of the world. China apparently boasts a history of aurora records longer than Japan, with a history lasting before Christ himself. “Being Japanese, I’m not familiar with British, Finnish or Vietnamese cultures,” said Professor Kataoka. “But every country has literature researchers and scientists who can easily collaborate and perform interdisciplinary research.” And by doing so, it’s not just science which benefits from it, but so is ancient art whose beauty and relevance gains longevity.

Space & Physics

Atoms Speak Out: Physicists Use Electrons as Messengers to Unlock Secrets of the Nucleus

Physicists at MIT have devised a table-top method to peer inside an atom’s nucleus using the atom’s own electrons

Physicists at MIT have developed a pioneering method to look inside an atom’s nucleus — using the atom’s own electrons as tiny messengers within molecules rather than massive particle accelerators.

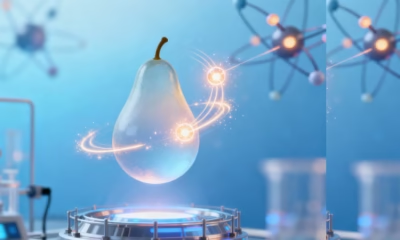

In a study published in Science, the researchers demonstrated this approach using molecules of radium monofluoride, which pair a radioactive radium atom with a fluoride atom. The molecules act like miniature laboratories where electrons naturally experience extremely strong electric fields. Under these conditions, some electrons briefly penetrate the radium nucleus, interacting directly with protons and neutrons inside. This rare intrusion leaves behind a measurable energy shift, allowing scientists to infer details about the nucleus’ internal structure.

The team observed that these energy shifts, though minute — about one millionth of the energy of a laser photon — provide unambiguous evidence of interactions occurring inside the nucleus rather than outside it. “We now have proof that we can sample inside the nucleus,” said Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz, the Thomas A. Franck Associate Professor of Physics at MIT, in a statement. “It’s like being able to measure a battery’s electric field. People can measure its field outside, but to measure inside the battery is far more challenging. And that’s what we can do now.”

Traditionally, exploring nuclear interiors required kilometer-long particle accelerators to smash high-speed beams of electrons into targets. The MIT technique, by contrast, achieves similar insight with a table-top molecular setup. It makes use of the molecule’s natural electric environment to magnify these subtle interactions.

The radium nucleus, unlike most which are spherical, has an asymmetric “pear” shape that makes it a powerful system for studying violations of fundamental physical symmetries — phenomena that could help explain why the universe contains far more matter than antimatter. “The radium nucleus is predicted to be an amplifier of this symmetry breaking, because its nucleus is asymmetric in charge and mass, which is quite unusual,” Garcia Ruiz explained.

To conduct their experiments, the researchers produced radium monofluoride molecules at CERN’s Collinear Resonance Ionization Spectroscopy (CRIS) facility, trapped and cooled them in laser-guided chambers, and then measured laser-induced energy transitions with extreme precision. The work involved MIT physicists Shane Wilkins, Silviu-Marian Udrescu, and Alex Brinson, alongside international collaborators.

“Radium is naturally radioactive, with a short lifetime, and we can currently only produce radium monofluoride molecules in tiny quantities,” said Wilkins. “We therefore need incredibly sensitive techniques to be able to measure them.”

As Udrescu added, “When you put this radioactive atom inside of a molecule, the internal electric field that its electrons experience is orders of magnitude larger compared to the fields we can produce and apply in a lab. In a way, the molecule acts like a giant particle collider and gives us a better chance to probe the radium’s nucleus.”

Going forward, the MIT team aims to cool and align these molecules so that the orientation of their pear-shaped nuclei can be controlled for even more detailed mapping. “Radium-containing molecules are predicted to be exceptionally sensitive systems in which to search for violations of the fundamental symmetries of nature,” Garcia Ruiz said. “We now have a way to carry out that search”

Space & Physics

Physicists Double Precision of Optical Atomic Clocks with New Laser Technique

MIT researchers develop a quantum-enhanced method that doubles the precision and stability of optical atomic clocks, paving the way for portable, ultra-accurate timekeeping.

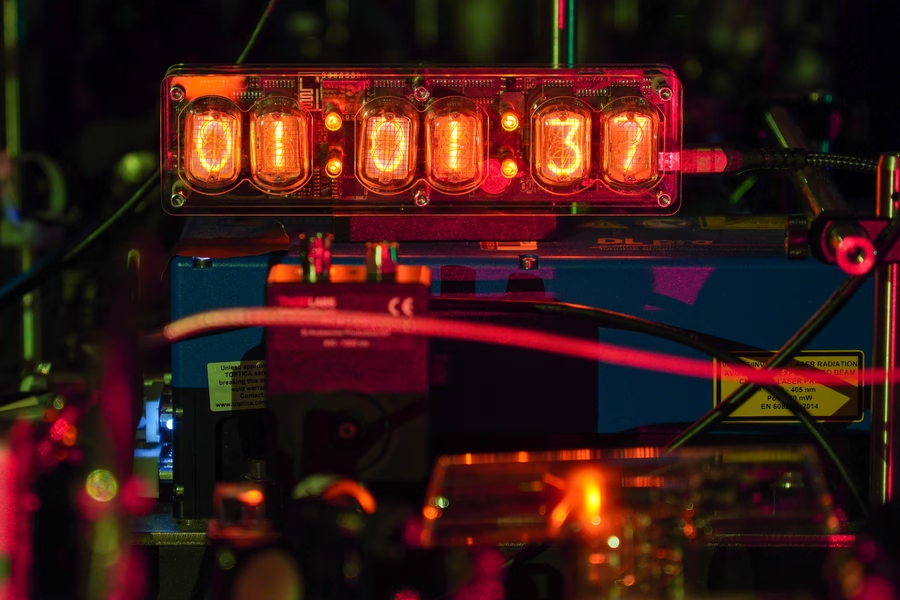

MIT physicists have unveiled a new technique that could significantly improve the precision and stability of next-generation optical atomic clocks, devices that underpin everything from mobile transactions to navigation apps. In a recent media statement, the MIT team explained: “Every time you check the time on your phone, make an online transaction, or use a navigation app, you are depending on the precision of atomic clocks. An atomic clock keeps time by relying on the ‘ticks’ of atoms as they naturally oscillate at rock-steady frequencies.”

Current atomic clocks rely on cesium atoms tracked with lasers at microwave frequencies, but scientists are advancing to clocks based on faster-ticking atoms like ytterbium, which can be tracked with lasers at higher, optical frequencies and discern intervals up to 100 trillion times per second.

A research group at MIT, led by Vladan Vuletić, the Lester Wolfe Professor of Physics, detailed that their newly developed method harnesses a laser-induced “global phase” in ytterbium atoms and boosts this effect using quantum amplification. Vuletić stated, “We think our method can help make these clocks transportable and deployable to where they’re needed.” The approach, called global phase spectroscopy, doubles the precision of an optical atomic clock, enabling it to resolve twice as many ticks per second compared to standard setups, and promises further gains with increasing atom counts.

The technique could pave the way for portable optical atomic clocks able to measure all manner of phenomena in various locations. Vuletić summarized the broader scientific ambitions: “With these clocks, people are trying to detect dark matter and dark energy, and test whether there really are just four fundamental forces, and even to see if these clocks can predict earthquakes.”

The MIT team has previously demonstrated improved clock precision by quantumly entangling hundreds of ytterbium atoms and using time reversal tricks to amplify their signals. Their latest advance applies these methods to much faster optical frequencies, where stabilizing the clock laser has always been a major challenge. “When you have atoms that tick 100 trillion times per second, that’s 10,000 times faster than the frequency of microwaves,” said Vuletić in the statement. Their experiments revealed a surprisingly useful “global phase” information about the laser frequency, previously thought irrelevant, unlocking the potential for even greater accuracy.

The research, led by Vuletić and joined by Leon Zaporski, Qi Liu, Gustavo Velez, Matthew Radzihovsky, Zeyang Li, Simone Colombo, and Edwin Pedrozo-Peñafiel of the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, was published in Nature. They believe the technical benefits of the new method will make atomic clocks easier to run and enable stable, transportable clocks fit for future scientific exploration, including earthquake prediction, fundamental physics, and global time standards.

Space & Physics

Nobel Prize in Physics: Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis Honoured for Pioneering Quantum Discoveries

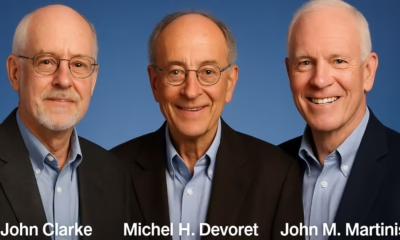

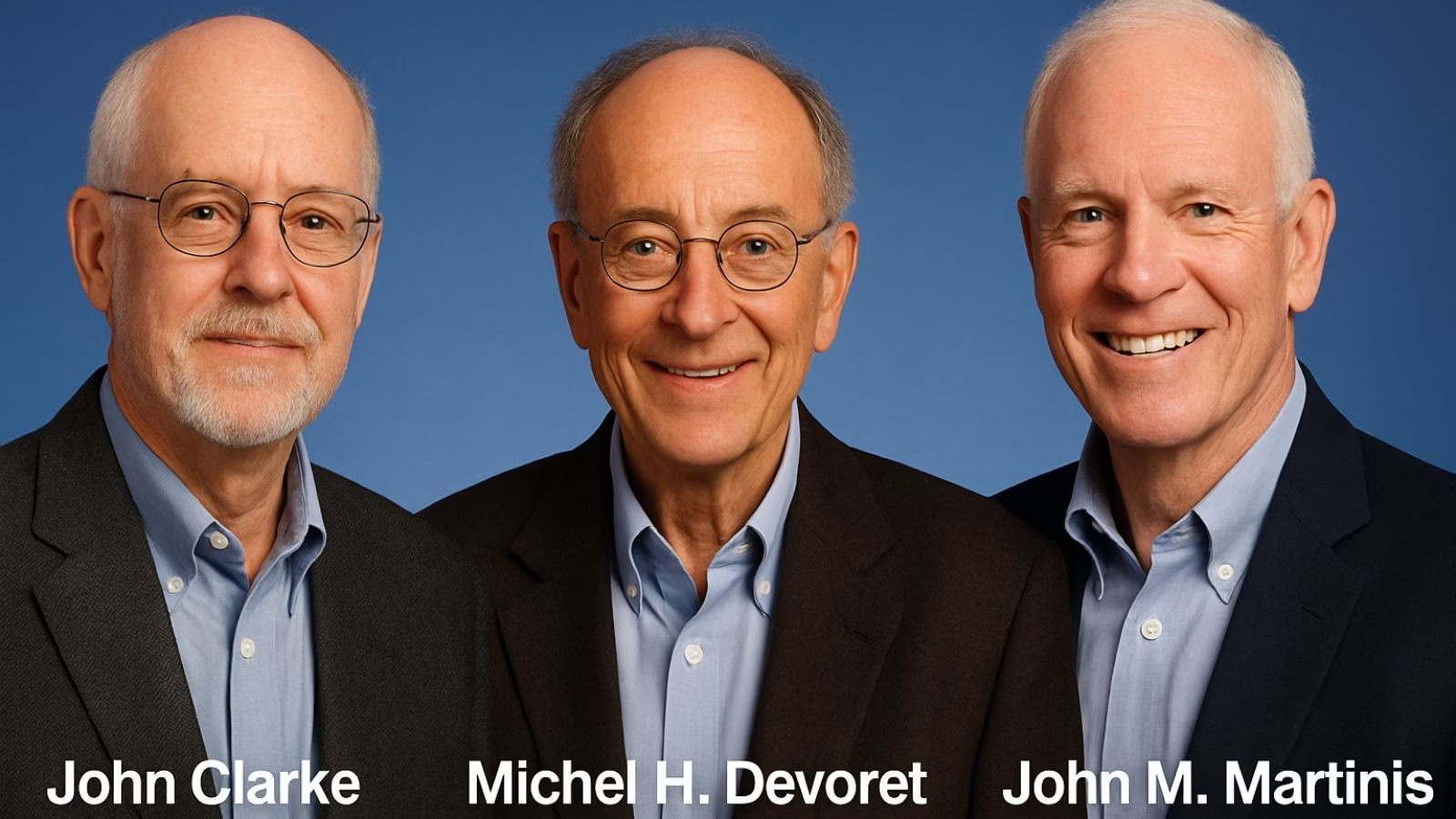

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics honours John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for revealing how entire electrical circuits can display quantum behaviour — a discovery that paved the way for modern quantum computing.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for their landmark discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit, an innovation that laid the foundation for today’s quantum computing revolution.

Announcing the prize, Olle Eriksson, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said, “It is wonderful to be able to celebrate the way that century-old quantum mechanics continually offers new surprises. It is also enormously useful, as quantum mechanics is the foundation of all digital technology.”

The Committee described their discovery as a “turning point in understanding how quantum mechanics manifests at the macroscopic scale,” bridging the gap between classical electronics and quantum physics.

John Clarke: The SQUID Pioneer

British-born John Clarke, Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, is celebrated for his pioneering work on Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) — ultra-sensitive detectors of magnetic flux. His career has been marked by contributions that span superconductivity, quantum amplifiers, and precision measurements.

Clarke’s experiments in the early 1980s provided the first clear evidence of quantum behaviour in electrical circuits — showing that entire electrical systems, not just atoms or photons, can obey the strange laws of quantum mechanics.

A Fellow of the Royal Society, Clarke has been honoured with numerous awards including the Comstock Prize (1999) and the Hughes Medal (2004).

Michel H. Devoret: Architect of Quantum Circuits

French physicist Michel H. Devoret, now the Frederick W. Beinecke Professor Emeritus of Applied Physics at Yale University, has been one of the intellectual architects of quantronics — the study of quantum phenomena in electrical circuits.

After earning his PhD at the University of Paris-Sud and completing a postdoctoral fellowship under Clarke at Berkeley, Devoret helped establish the field of circuit quantum electrodynamics (cQED), which underpins the design of modern superconducting qubits.

His group’s innovations — from the single-electron pump to the fluxonium qubit — have set performance benchmarks in quantum coherence and control. Devoret is also a recipient of the Fritz London Memorial Prize (2014) and the John Stewart Bell Prize, and is a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

John M. Martinis: Building the Quantum Processor

American physicist John M. Martinis, who completed his PhD at UC Berkeley under Clarke’s supervision, translated these quantum principles into the hardware era. His experiments demonstrated energy level quantisation in Josephson junctions, one of the key results now honoured by the Nobel Committee.

Martinis later led Google’s Quantum AI lab, where his team in 2019 achieved the world’s first demonstration of quantum supremacy — showing a superconducting processor outperforming the fastest classical supercomputer on a specific task.

A former professor at UC Santa Barbara, Martinis continues to be a leading voice in quantum computing research and technology development.

A Legacy of Quantum Insight

Together, the trio’s discovery, once seen as a niche curiosity in superconducting circuits, has become the cornerstone of the global quantum revolution. Their experiments proved that macroscopic electrical systems can display quantised energy states and tunnel between them, much like subatomic particles.

Their work, as the Nobel citation puts it, “opened a new window into the quantum behaviour of engineered systems, enabling technologies that are redefining computation, communication, and sensing.”

Space & Physics5 months ago

Space & Physics5 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

Earth5 months ago

Earth5 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

The Sciences4 months ago

The Sciences4 months agoHow a Human-Inspired Algorithm Is Revolutionizing Machine Repair Models in the Wake of Global Disruptions

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoMIT Physicists Capture First-Ever Images of Freely Interacting Atoms in Space