Health

UFS study finds emerging pathogen inside brown locusts

Study Reveals Brown Locusts as Carriers of Pathogenic Yeasts Linked to Human Infections

A new study conducted by researchers from the University of the Free State (UFS), the National Health Laboratory Service, and the University of Venda has revealed for the first time that common brown locusts can carry pathogenic yeasts, including Candida auris, a fungus capable of causing severe infections in humans, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems or those seriously ill.

The study, titled South African brown locusts, Locustana pardalina, hosts fluconazole-resistant, Candidozyma (Candida) auris (Clade III), uncovers the presence of the disease-causing yeast C. auris in the digestive tracts of locusts. This discovery highlights the potential for locusts to spread this emerging pathogen. The research began in April 2022, with 20 adult locusts collected during a significant locust outbreak in the semi-arid Eastern Karoo region of the Eastern Cape, which lasted from September 2021 to May 2022. The study is currently under peer review.

According to Prof. Carlien Pohl-Albertyn, National Research Foundation (NRF) SARChI Research Chair in Pathogenic Yeasts, the researchers isolated three strains of C. auris from different locusts, two of which also contained strains of Candida orthopsilosis, another potentially pathogenic yeast. “The fact that we were able to isolate C. auris from 15% of the sampled locusts, using non-selective media and a non-restrictive temperature of 30°C, may indicate that C. auris is abundant in the locusts and that specific selective isolation is not mandatory,” said Prof. Pohl-Albertyn.

The study also found C. auris in both the fore- and hindguts of the locusts. The foregut, responsible for food intake and partial digestion, likely serves as the entry point for the yeast via the locust’s feeding activities. The hindgut confirmed that C. auris can survive digestion and may be excreted back into the environment through faeces.

While C. auris poses a significant risk to individuals with compromised immune systems, Prof. Pohl-Albertyn emphasized that healthy humans are not at great risk. “There is currently no proof that ingestion may be harmful to them,” she explained. However, she warned that the yeast could pose dangers to immunocompromised individuals, even though few people in South Africa are in direct contact with locusts.

One of the C. auris strains studied in-depth showed decreased susceptibility to fluconazole, a common antifungal drug, underscoring the need for new antifungal treatments. “This highlights the urgent need to discover and develop new antifungal drugs,” Prof. Pohl-Albertyn added.

The study also raises concerns about how locusts could potentially spread C. auris to other animals, such as birds, and, in some regions, even humans. “The fact that locusts are a food source for other animals could lead to eventual distribution of the yeast to people,” Prof. Pohl-Albertyn noted. In countries where locusts are consumed by humans, direct transmission could be more likely.

This research contributes to understanding the natural hosts of emerging pathogens and their role in spreading these diseases. Prof. Pohl-Albertyn emphasized the importance of understanding how C. auris emerged as a pathogen in multiple countries and how environmental factors may have shaped its evolution. “This has implications for the prevention of the spread of this specific yeast species, as well as our preparedness for new pathogenic yeasts that may be emerging from the environment,” she concluded.

Health

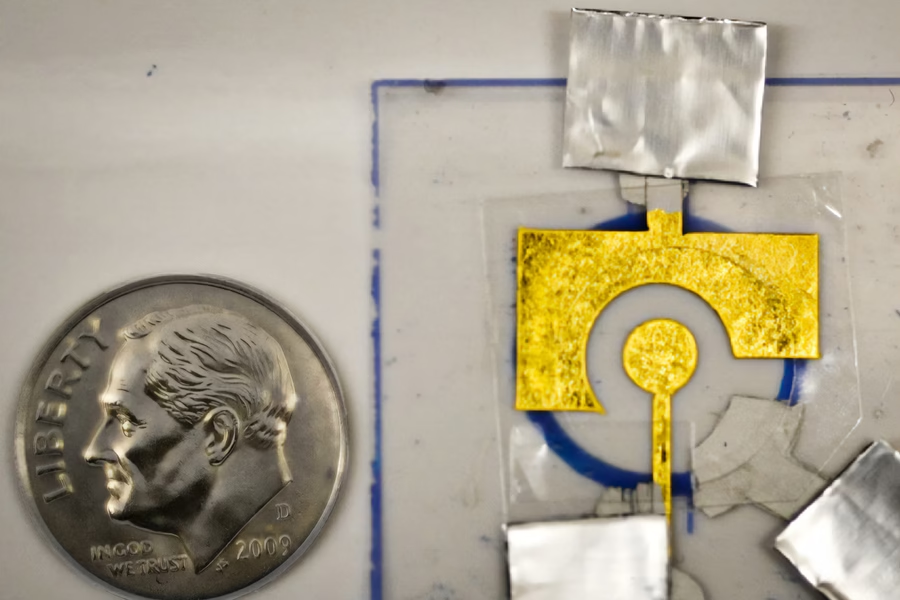

Researchers Unveil 50-Cent DNA Sensors That Could Revolutionize Disease Diagnosis

The innovation lies in a low-cost electrochemical sensor stabilized with a polymer coating, which allows the device to be stored for months at high temperatures and used far from traditional lab settings

In a breakthrough that could make life-saving diagnostics accessible to millions, MIT researchers have developed a disposable, DNA-coated sensor capable of detecting diseases like cancer, HIV, and influenza — all for just 50 cents. The innovation lies in a low-cost electrochemical sensor stabilized with a polymer coating, which allows the device to be stored for months at high temperatures and used far from traditional lab settings.

At the heart of this sensor is a CRISPR-based enzyme system. When the sensor detects a target disease gene, the enzyme — acting like a molecular lawnmower — begins to shred DNA on the electrode, disrupting the electric signal and indicating a positive result.

“Our focus is on diagnostics that many people have limited access to, and our goal is to create a point-of-use sensor,” said Ariel Furst, MIT chemical engineering professor and senior author of the study, in a media statement. “People wouldn’t even need to be in a clinic to use it. You could do it at home.”

Previously, such sensors faced a major hurdle: the DNA coating degraded rapidly, requiring immediate use and refrigerated storage. Furst’s team overcame this by using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) — a cheap and widely available polymer — to form a protective film over the DNA, significantly extending shelf life.

The sensors were tested to successfully detect PCA3, a prostate cancer biomarker found in urine, even after two months of storage at 150°F. The technology builds on Furst’s earlier work that enabled detection of HIV and HPV genetic material using similar CRISPR-based methods.

“This is the same core technology used in glucose meters, but adapted with programmable DNA,” said lead author Xingcheng Zhou, an MIT graduate student. “It’s inexpensive, portable, and extremely versatile.”

The team now aims to expand testing for other infectious and emerging diseases. They’ve been accepted into MIT’s delta v venture accelerator, signaling commercial interest and real-world application potential. The ability to ship sensors without refrigeration could be transformative for low-resource and remote settings.

“Our limitation before was that we had to make the sensors on site,” added Furst. “Now that we can protect them, we can ship them. That allows us to access a lot more rugged or non-ideal environments for testing.”

With further development, these pocket-sized DNA sensors could redefine early disease detection — from rural clinics to living rooms.

Health

Teak Leaf Extract Emerges as Eco-Friendly Shield Against Harmful Laser Rays

Raman Research Institute scientists unlock sustainable alternative for laser safety in line with green tech goals

In a significant step toward sustainable photonic technologies, scientists from the Raman Research Institute (RRI), an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, have discovered that teak leaf extract can serve as an effective, natural shield against harmful laser radiation. This breakthrough offers new potential for protecting both sensitive optical sensors and human eyes from high-intensity lasers used in medical, industrial, and defense applications.

The team has found that the otherwise discarded leaves of the teak tree (Tectona grandis L.f) are rich in anthocyanins, natural pigments responsible for their reddish-brown colour. When exposed to light, these pigments exhibit nonlinear optical (NLO) properties, allowing them to absorb intense laser beams—a key feature required for laser safety gear.

The discovery, recently published in the Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, proposes a non-toxic, biodegradable, and cost-effective alternative to conventional synthetic materials like graphene and metal nanoparticles, which are often expensive and environmentally hazardous.

“Teak leaves are a rich source of natural pigments such as anthocyanin… We explored the potential of teak leaf extract as an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic dyes in the field of nonlinear optics,” said Beryl C, DST Women Scientist at RRI, in a media statement issued by the government.

To extract this natural dye, researchers dried and powdered teak leaves, soaked them in solvents, and processed the mixture using ultrasonication and centrifugation. The resulting reddish-brown liquid was then tested with green laser beams under continuous and pulsed conditions.

Using advanced techniques like Z-scan and Spatial Self-Phase Modulation (SSPM), the dye demonstrated reverse saturable absorption (RSA)—a rare and desirable trait where the material absorbs more light as the intensity increases, effectively acting as a self-regulating shield against laser exposure.

This development is particularly crucial as laser technologies become increasingly prevalent in everyday environments—from surgical devices and industrial cutters to military-grade systems. By offering a natural and renewable solution to a global safety challenge, the RRI team has opened the door to a future of eco-conscious optical safety equipment, such as laser-resistant eyewear, coatings, and sensor shields.

Researchers also indicated that further studies will focus on enhancing the stability and commercial usability of the dye for long-term deployment.

This innovation aligns with the principles of Industry 5.0, emphasizing human-centered and environmentally responsible technology, and showcases how indigenous, sustainable resources can play a pivotal role in global tech solutions.

Health

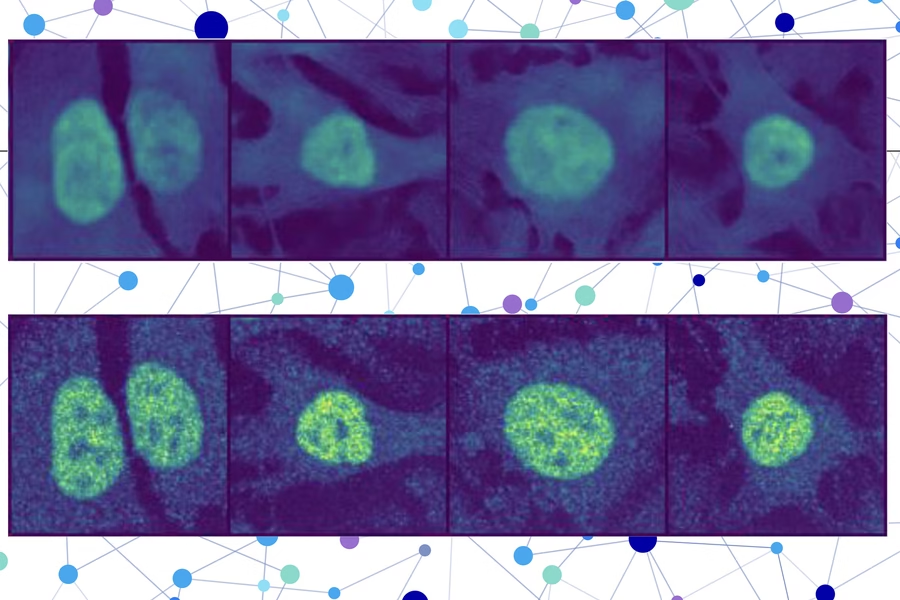

PUPS – the AI tool that can predict where exactly proteins are in human cells

Dubbed, the Prediction of Unseen Proteins’ Subcellular Localization (or PUPS), the AI tool can account for the effects of protein mutations and cellular stress—key factors in disease progression.

Researchers from MIT, Harvard University, and the Broad Institute have unveiled a groundbreaking artificial intelligence tool that can accurately predict where proteins are located within any human cell, even if both the protein and cell line have never been studied before. The method – Prediction of Unseen Proteins’ Subcellular Localization (or PUPS) – marks a major advancement in biological research and could significantly streamline disease diagnosis and drug discovery.

Protein localization—the precise location of a protein within a cell—is key to understanding its function. Misplaced proteins are known to contribute to diseases like Alzheimer’s, cystic fibrosis, and cancer. However, identifying protein locations manually is expensive and slow, particularly given the vast number of proteins in a single cell.

The new technique leverages a protein language model and a sophisticated computer vision system. It produces a detailed image that highlights where the protein is likely to be located at the single-cell level, offering far more precise insights than many existing models, which average results across all cells of a given type.

“You could do these protein-localization experiments on a computer without having to touch any lab bench, hopefully saving yourself months of effort. While you would still need to verify the prediction, this technique could act like an initial screening of what to test for experimentally,” said Yitong Tseo, a graduate student in MIT’s Computational and Systems Biology program and co-lead author of the study, in a media statement.

Tseo’s co-lead author, Xinyi Zhang, emphasized the model’s ability to generalize: “Most other methods usually require you to have a stain of the protein first, so you’ve already seen it in your training data. Our approach is unique in that it can generalize across proteins and cell lines at the same time,” she said in a media statement.

PUPS was validated through laboratory experiments and shown to outperform baseline AI methods in predicting protein locations with greater accuracy. The tool is also capable of accounting for the effects of protein mutations and cellular stress—key factors in disease progression.

Published in Nature Methods, the research was led by senior authors Fei Chen of Harvard and the Broad Institute, and Caroline Uhler, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor at MIT. Future goals include enabling PUPS to analyze protein interactions and make predictions in live human tissue rather than cultured cells.

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoStarliner crew challenge rhetoric, says they were never “stranded”

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoCould dark energy be a trick played by time?

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoHow IIT Kanpur is Paving the Way for a Solar-Powered Future in India’s Energy Transition

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoSunita Williams aged less in space due to time dilation

-

Learning & Teaching4 months ago

Learning & Teaching4 months agoCanine Cognitive Abilities: Memory, Intelligence, and Human Interaction

-

Earth2 months ago

Earth2 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Women In Science3 months ago

Women In Science3 months agoNeena Gupta: Shaping the Future of Algebraic Geometry

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoSustainable Farming: The Microgreens Model from Kerala, South India