Space & Physics

The various avatars of the Hall effect

In this second article of Ed Publica’s series on the Hall effect, Dr. Saraubh Basu examines the physics of the Hall effect variants discovered over the course of the past century.

This is the second article of Ed Publica’s series on the Hall effect, which covers the various manifestations of the Hall effect. You can read the first article here.

The ‘anomalous’ Hall effect

In 1881, just two years after Edwin Hall discovered the eponymous Hall effect, he spotted an anomaly when replicating the effect with ferromagnets.

He had observed a tenfold deflection of electric charges this time around, compared to non-magnetic conductors.

Suspecting the magnetic properties played a role, this avatar of the Hall effect is dubbed the anomalous Hall effect. The word ‘anomalous’ is used owing to the fact that external magnetic field no longer remains as a stringent requirement for the Hall effect; instead, the intrinsic magnetization (for instance, the ferromagnet in the above example) fulfils that criterion.

The physicist Edwin Hall. Credit: Wikimedia

The Hall resistivity in ferromagnets increase steeply under the presence of very weak magnetic fields. However, in stronger magnetic fields, the Hall resistivity doesn’t increase further very much. This saturation is rather strange, for it is in contrast to the classical Hall effect where the Hall resistivity maintains its steady growth.

There are several other effects that play a crucial role in determining the anomalous Hall resistivity, thus making it a complicated phenomenon that physicists lack comprehensive understanding about, in comparison to the various other avatars of the Hall effect.

Quantum avatar(s)

The fact that a simple lab experiment showed how the Hall resistivity can be expressed as an equation that contains merely constants, opened up a a plethora of research to understand the cause of this ‘universality’. For it hinted to the involvement of a very fundamental phenomenon.

In 1980, Klaus von Klitzing discovered the quantum avatar of the Hall effect was detected. He was amidst research at a magnetic facility in Grenoble, France, working to improve electron mobility in metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors (MOSFET). These are transistors that typically operate at extremely low temperatures and under intense magnetic fields.

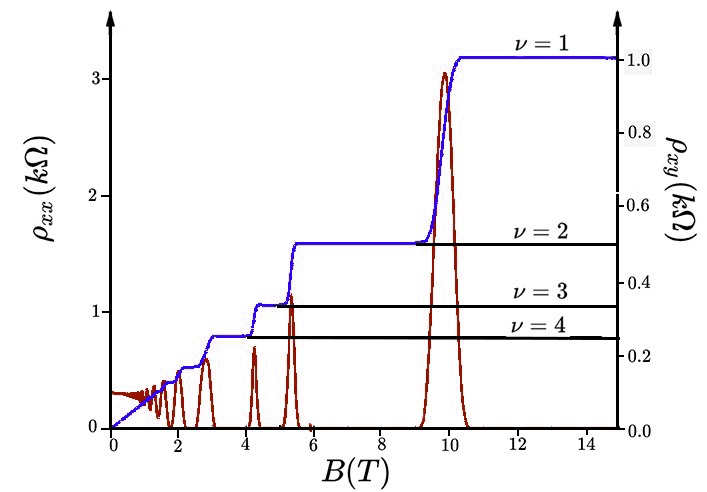

von Klitzing observed his sample’s Hall resistivity assuming discretized values. This means the resistivity jumps in steps, by a fixed amount that can be scaled as multiples of an integer number (includes 0 along with whole numbers such as 1,2,3, and so on). This discretization reveals the underlying quantum mechanical behavior that has been unraveled at long last – thus bearing its name – the integer quantum Hall effect. von Klitzing later won the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1985 for this work.

The plot here depicts the transverse and longitudinal Hall resistivity (y-axis) increasing in integer steps as the magnetic field (x-axis) increases. This is due to the integer quantum Hall effect. Credit: Wikimedia

But the quantization isn’t limited to integer multiples. In fact, two years later, the fractional quantum Hall effect was observed in experiments. It was shown there were about 100 fractions, including those that aren’t whole numbers that were now in the formula.

Robert Laughlin, who would later win a share of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physics, proposed a theory to explain the observations. It boils down to the interaction among electrons, either due to the Coulombic repulsion force or the Pauli exclusion principle.

These interacts would eventually split the degeneracy of these enormously degenerate Landau energy levels. These are quantum states occupied by electrons that complete circular revolutions under the influence of an external magnetic field. Splitting these degeneracies, lead to the opening of an energy gap, for the fractional quantum Hall effect to be observed.

‘Spin’ avatar(s)

Just as there are electric charges in nature, so are there spin currents found in nature. ‘Spin’ is a key property found in quantum particles. Unlike what the name suggests, these quantum particles don’t spin or rotate about any axis passing through them. However, these particles carry an angular momentum as though it does spin.

In 1971, before von Klitzing observed the quantum Hall effect, Mikhail Dyakonov and Vladimir Perel hypothesized the spin Hall effect.

In this avatar of the Hall effect, quantum spins of opposite kinds accumulate at the edges of the sample, orthogonal to the direction in which the charge current passes.

The spin selection can be facilitated by the spin-orbit coupling. This refers to the modified energy levels in an atom when the electron’s motion is under the influence on the magnetic field generated by the nucleus. Strong coupling may be intrinsic to doped semiconductors. The proposal has triggered intense investigation of the phenomenon, with first experimental observations of the spin Hall effect seen in n-doped semiconductors and two-dimensional hole gases.

Quantum spins don’t really look like the depiction above, which is meant to showcase a fact that particles like electrons do have an intrinsic angular momentum nonetheless. Credit: Karthik / Ed Publica

For more than a decade, studies concerning the spin current and its application to novel spintronics (or spin electronics) have received plethora of attention. This is with regard to efficiently generating, manipulating and detecting spin accumulation in a sample material. Some progress has also occurred from the device fabrication perspective via techniques such as spin injection, among others.

A major advantage in dealing with the spin current lies in the non-dissipative (or very less dissipation) nature which arises owing to the time reversal invariance of the spin current. This presents a non-dissipative scenario (unlike the dissipative effects seen with charged currents), thus making it quite advantageous for spin transport phenomena.

Furthermore, a quantized version of the spin Hall effect exists, with mercury telluride and cadmium telluride quantum well superlattices, showcasing this effect. In 2005, a quantum treatment was proposed by Charles Kane and Eugene Mele, in the form of a tight binding toy model of electrons operating in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice.

In fact, the ‘wonder material’ graphene, which is a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice constituting carbon atoms, does satisfy some key requirements for the quantum spin Hall effect. However, it lacks a large spin-orbit coupling among other requirements.

Nonetheless, graphene’s ability to entertain the quantum spin Hall effect, makes it a prospective candidate to find applications in next-generation spintronic devices.

Space & Physics

Nobel Prize in Physics: Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis Honoured for Pioneering Quantum Discoveries

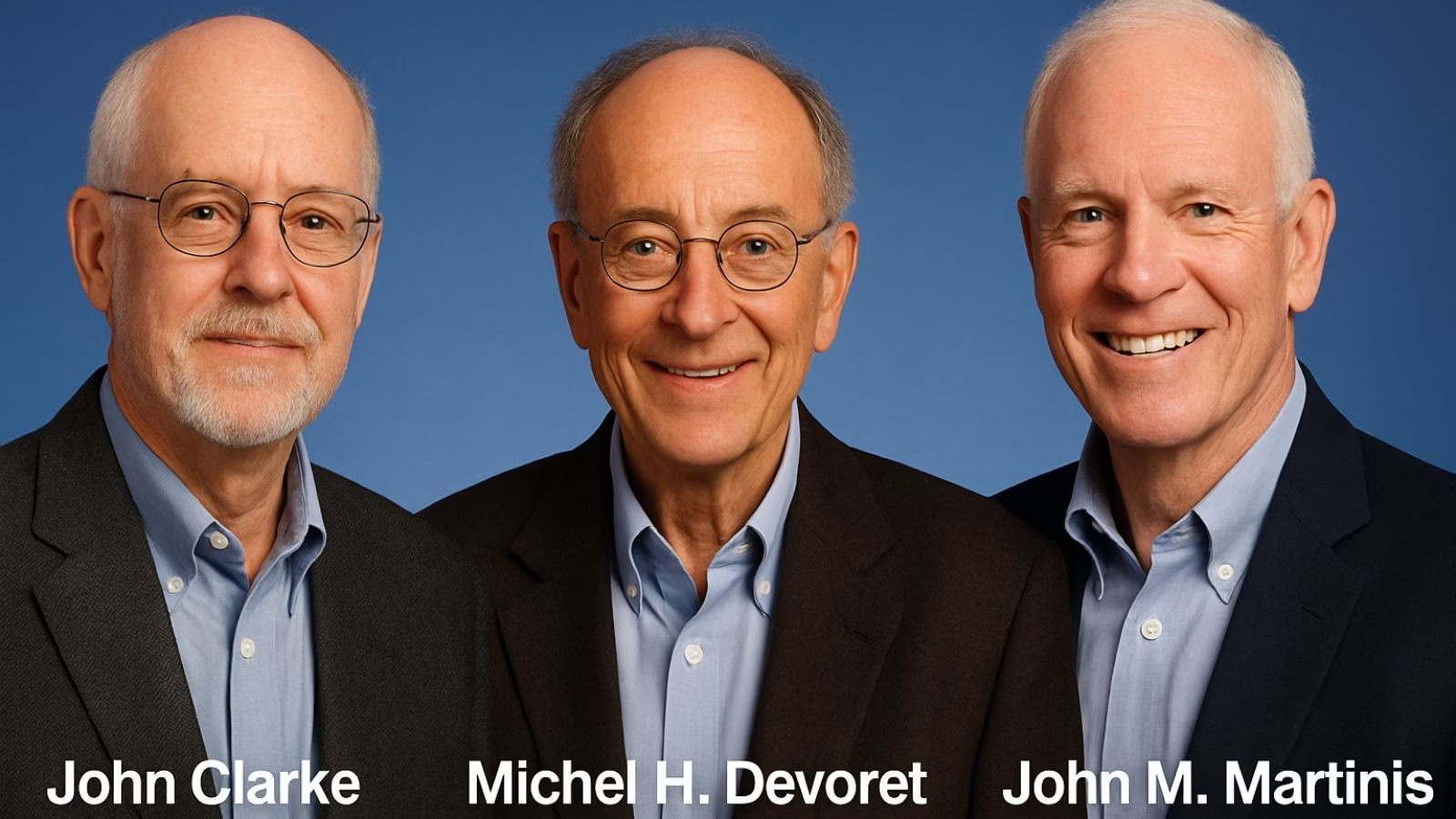

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics honours John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for revealing how entire electrical circuits can display quantum behaviour — a discovery that paved the way for modern quantum computing.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for their landmark discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit, an innovation that laid the foundation for today’s quantum computing revolution.

Announcing the prize, Olle Eriksson, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said, “It is wonderful to be able to celebrate the way that century-old quantum mechanics continually offers new surprises. It is also enormously useful, as quantum mechanics is the foundation of all digital technology.”

The Committee described their discovery as a “turning point in understanding how quantum mechanics manifests at the macroscopic scale,” bridging the gap between classical electronics and quantum physics.

John Clarke: The SQUID Pioneer

British-born John Clarke, Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, is celebrated for his pioneering work on Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) — ultra-sensitive detectors of magnetic flux. His career has been marked by contributions that span superconductivity, quantum amplifiers, and precision measurements.

Clarke’s experiments in the early 1980s provided the first clear evidence of quantum behaviour in electrical circuits — showing that entire electrical systems, not just atoms or photons, can obey the strange laws of quantum mechanics.

A Fellow of the Royal Society, Clarke has been honoured with numerous awards including the Comstock Prize (1999) and the Hughes Medal (2004).

Michel H. Devoret: Architect of Quantum Circuits

French physicist Michel H. Devoret, now the Frederick W. Beinecke Professor Emeritus of Applied Physics at Yale University, has been one of the intellectual architects of quantronics — the study of quantum phenomena in electrical circuits.

After earning his PhD at the University of Paris-Sud and completing a postdoctoral fellowship under Clarke at Berkeley, Devoret helped establish the field of circuit quantum electrodynamics (cQED), which underpins the design of modern superconducting qubits.

His group’s innovations — from the single-electron pump to the fluxonium qubit — have set performance benchmarks in quantum coherence and control. Devoret is also a recipient of the Fritz London Memorial Prize (2014) and the John Stewart Bell Prize, and is a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

John M. Martinis: Building the Quantum Processor

American physicist John M. Martinis, who completed his PhD at UC Berkeley under Clarke’s supervision, translated these quantum principles into the hardware era. His experiments demonstrated energy level quantisation in Josephson junctions, one of the key results now honoured by the Nobel Committee.

Martinis later led Google’s Quantum AI lab, where his team in 2019 achieved the world’s first demonstration of quantum supremacy — showing a superconducting processor outperforming the fastest classical supercomputer on a specific task.

A former professor at UC Santa Barbara, Martinis continues to be a leading voice in quantum computing research and technology development.

A Legacy of Quantum Insight

Together, the trio’s discovery, once seen as a niche curiosity in superconducting circuits, has become the cornerstone of the global quantum revolution. Their experiments proved that macroscopic electrical systems can display quantised energy states and tunnel between them, much like subatomic particles.

Their work, as the Nobel citation puts it, “opened a new window into the quantum behaviour of engineered systems, enabling technologies that are redefining computation, communication, and sensing.”

Space & Physics

The Tiny Grip That Could Reshape Medicine: India’s Dual-Trap Optical Tweezer

Indian scientists build new optical tweezer module—set to transform single-molecule research and medical Innovation

In an inventive leap that could open up new frontiers in neuroscience, drug development, and medical research, scientists in India have designed their own version of a precision laboratory tool known as the dual-trap optical tweezers system. By creating a homegrown solution to manipulate and measure forces on single molecules, the team brings world-class technology within reach of Indian researchers—potentially igniting a wave of scientific discoveries.

Optical tweezers, a Nobel Prize-winning invention from 2018, use focused beams of light to grab and move microscopic objects with extraordinary accuracy. The technique has become indispensable for measuring tiny forces and exploring the mechanics of DNA, proteins, living cells, and engineered nanomaterials. Yet, decades after their invention, conventional optical tweezers systems sometimes fall short for today’s most challenging experiments.

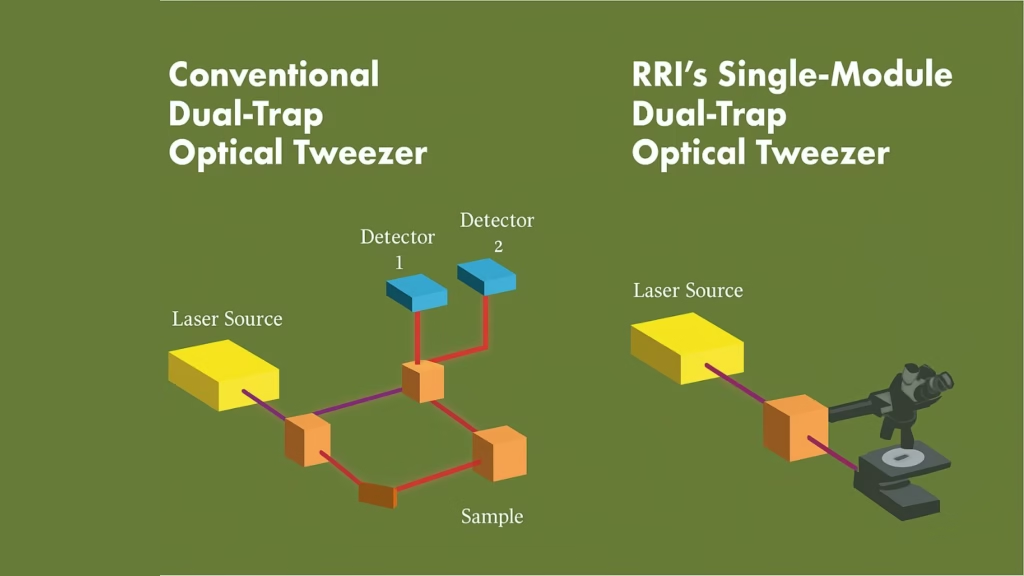

Researchers at the Raman Research Institute (RRI), an autonomous institute backed by India’s Department of Science and Technology in Bengaluru, have now introduced a smart upgrade that addresses long-standing pitfalls of dual-trap tweezers. Traditional setups rely on measuring the light that passes through particles trapped in two separate beams—a method prone to signal “cross-talk.” This makes simultaneous, independent measurement difficult, diminishing both accuracy and versatility.

The new system pioneers a confocal detection scheme. In a media statement, Md Arsalan Ashraf, a doctoral scholar at RRI, explained, “The unique optical trapping scheme utilizes laser light scattered back by the sample for detecting trapped particle position. This technique pushes past some of the long-standing constraints of dual-trap configurations and removes signal interference. The single-module design integrates effortlessly with standard microscopy frameworks,” he said.

The refinement doesn’t end there. The system ensures that detectors tracking tiny particles remain perfectly aligned, even when the optical traps themselves move. The result: two stable, reliable measurement channels, zero interference, and no need for complicated re-adjustment mid-experiment—a frequent headache with older systems.

Traditional dual-trap designs have required costly and complex add-ons, sometimes even hijacking the features of laboratory microscopes and making additional techniques, such as phase contrast or fluorescence imaging, hard to use. “This new single-module trapping and detection design makes high-precision force measurement studies of single molecules, probing of soft materials including biological samples, and micromanipulation of biological samples like cells much more convenient and cost-effective,” said Pramod A Pullarkat, lead principal investigator at RRI, in a statement.

By removing cross-talk and offering robust stability—whether traps are close together, displaced, or the environment changes—the RRI team’s approach is not only easier to use but far more adaptable. Its plug-and-play module fits onto standard microscopes without overhauling their basic structure.

From the intellectual property point of view, this design may be a game-changer. By cracking the persistent problem of signal interference with minimalist engineering, the new setup enhances measurement precision and reliability—essential advantages for researchers performing delicate biophysical experiments on everything from molecular motors to living cells.

With the essential building blocks in place, the RRI team is now exploring commercial avenues to produce and distribute their single-module, dual-trap optical tweezer system as an affordable add-on for existing microscopes. The innovation stands to put advanced single-molecule force spectroscopy, long limited to wealthier labs abroad, into the hands of scientists across India—and perhaps spark breakthroughs across the biomedical sciences.

Space & Physics

New Magnetic Transistor Breakthrough May Revolutionize Electronics

A team of MIT physicists has created a magnetic transistor that could make future electronics smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient. By swapping silicon for a new magnetic semiconductor, they’ve opened the door to game-changing advancements in computing.

For decades, silicon has been the undisputed workhorse in transistors—the microscopic switches responsible for processing information in every phone, computer, and high-tech device. But silicon’s physical limits have long frustrated scientists seeking ever-smaller, more efficient electronics.

Now, MIT researchers have unveiled a major advance: they’ve replaced silicon with a magnetic semiconductor, introducing magnetism into transistors in a way that promises tighter, smarter, and more energy-saving circuits. This new ingredient, chromium sulfur bromide, makes it possible to control electricity flow with far greater efficiency and could even allow each transistor to “remember” information, simplifying circuit design for future chips.

“This lack of contamination enables their device to outperform existing magnetic transistors. Most others can only create a weak magnetic effect, changing the flow of current by a few percent or less. Their new transistor can switch or amplify the electric current by a factor of 10,” the MIT team said in a media statement. Their work, detailed in Physical Review Letters, outlines how this material’s stability and clean switching between magnetic states unlocks a new degree of control.

Chung-Tao Chou, MIT graduate student and co-lead author, explains in a media statement, “People have known about magnets for thousands of years, but there are very limited ways to incorporate magnetism into electronics. We have shown a new way to efficiently utilize magnetism that opens up a lot of possibilities for future applications and research.”

The device’s game-changing aspect is its ability to combine the roles of memory cell and transistor, allowing electronics to read and store information faster and more reliably. “Now, not only are transistors turning on and off, they are also remembering information. And because we can switch the transistor with greater magnitude, the signal is much stronger so we can read out the information faster, and in a much more reliable way,” said Luqiao Liu, MIT associate professor, in a media statement.

Moving forward, the team is looking to scale up their clean manufacturing process, hoping to create arrays of these magnetic transistors for broader commercial and scientific use. If successful, the innovation could usher in a new era of spintronic devices, where magnetism becomes as central to electronics as silicon is today.

-

Space & Physics5 months ago

Space & Physics5 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Earth6 months ago

Earth6 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoDid JWST detect “signs of life” in an alien planet?

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

-

Society6 months ago

Society6 months agoRabies, Bites, and Policy Gaps: One Woman’s Humane Fight for Kerala’s Stray Dogs