Space & Physics

The various avatars of the Hall effect

In this second article of Ed Publica’s series on the Hall effect, Dr. Saraubh Basu examines the physics of the Hall effect variants discovered over the course of the past century.

This is the second article of Ed Publica’s series on the Hall effect, which covers the various manifestations of the Hall effect. You can read the first article here.

The ‘anomalous’ Hall effect

In 1881, just two years after Edwin Hall discovered the eponymous Hall effect, he spotted an anomaly when replicating the effect with ferromagnets.

He had observed a tenfold deflection of electric charges this time around, compared to non-magnetic conductors.

Suspecting the magnetic properties played a role, this avatar of the Hall effect is dubbed the anomalous Hall effect. The word ‘anomalous’ is used owing to the fact that external magnetic field no longer remains as a stringent requirement for the Hall effect; instead, the intrinsic magnetization (for instance, the ferromagnet in the above example) fulfils that criterion.

The physicist Edwin Hall. Credit: Wikimedia

The Hall resistivity in ferromagnets increase steeply under the presence of very weak magnetic fields. However, in stronger magnetic fields, the Hall resistivity doesn’t increase further very much. This saturation is rather strange, for it is in contrast to the classical Hall effect where the Hall resistivity maintains its steady growth.

There are several other effects that play a crucial role in determining the anomalous Hall resistivity, thus making it a complicated phenomenon that physicists lack comprehensive understanding about, in comparison to the various other avatars of the Hall effect.

Quantum avatar(s)

The fact that a simple lab experiment showed how the Hall resistivity can be expressed as an equation that contains merely constants, opened up a a plethora of research to understand the cause of this ‘universality’. For it hinted to the involvement of a very fundamental phenomenon.

In 1980, Klaus von Klitzing discovered the quantum avatar of the Hall effect was detected. He was amidst research at a magnetic facility in Grenoble, France, working to improve electron mobility in metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors (MOSFET). These are transistors that typically operate at extremely low temperatures and under intense magnetic fields.

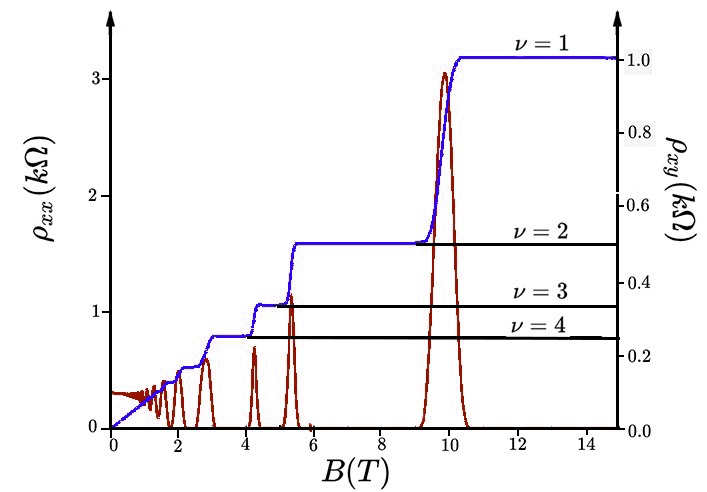

von Klitzing observed his sample’s Hall resistivity assuming discretized values. This means the resistivity jumps in steps, by a fixed amount that can be scaled as multiples of an integer number (includes 0 along with whole numbers such as 1,2,3, and so on). This discretization reveals the underlying quantum mechanical behavior that has been unraveled at long last – thus bearing its name – the integer quantum Hall effect. von Klitzing later won the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1985 for this work.

The plot here depicts the transverse and longitudinal Hall resistivity (y-axis) increasing in integer steps as the magnetic field (x-axis) increases. This is due to the integer quantum Hall effect. Credit: Wikimedia

But the quantization isn’t limited to integer multiples. In fact, two years later, the fractional quantum Hall effect was observed in experiments. It was shown there were about 100 fractions, including those that aren’t whole numbers that were now in the formula.

Robert Laughlin, who would later win a share of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physics, proposed a theory to explain the observations. It boils down to the interaction among electrons, either due to the Coulombic repulsion force or the Pauli exclusion principle.

These interacts would eventually split the degeneracy of these enormously degenerate Landau energy levels. These are quantum states occupied by electrons that complete circular revolutions under the influence of an external magnetic field. Splitting these degeneracies, lead to the opening of an energy gap, for the fractional quantum Hall effect to be observed.

‘Spin’ avatar(s)

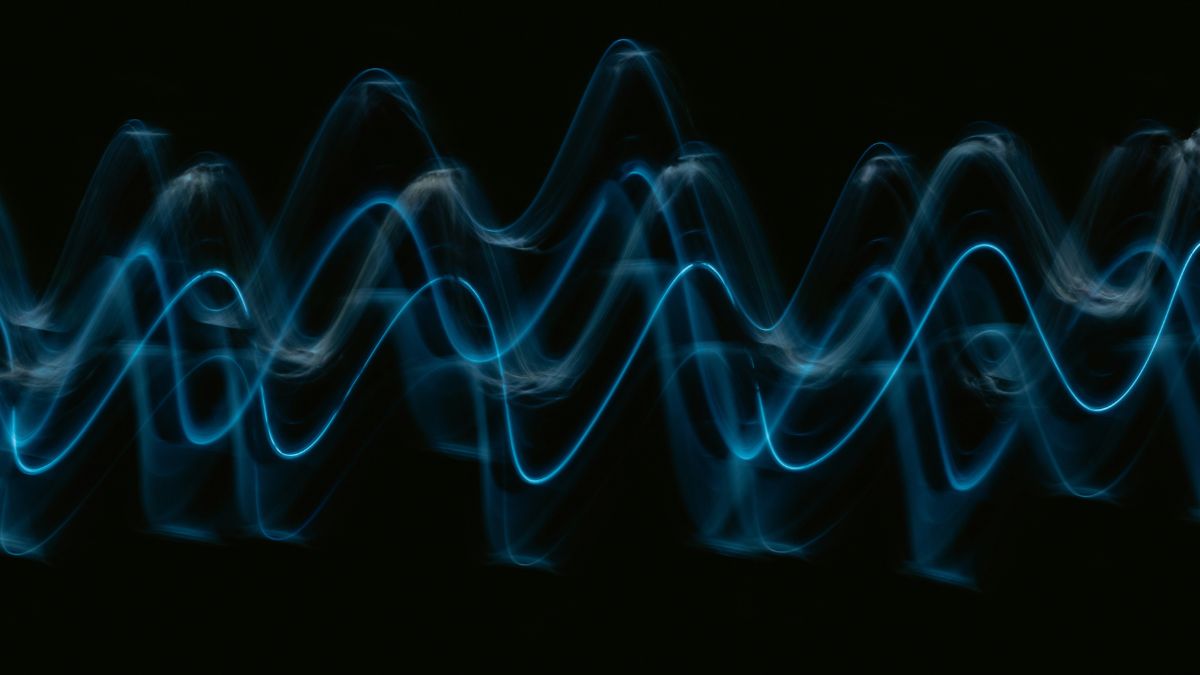

Just as there are electric charges in nature, so are there spin currents found in nature. ‘Spin’ is a key property found in quantum particles. Unlike what the name suggests, these quantum particles don’t spin or rotate about any axis passing through them. However, these particles carry an angular momentum as though it does spin.

In 1971, before von Klitzing observed the quantum Hall effect, Mikhail Dyakonov and Vladimir Perel hypothesized the spin Hall effect.

In this avatar of the Hall effect, quantum spins of opposite kinds accumulate at the edges of the sample, orthogonal to the direction in which the charge current passes.

The spin selection can be facilitated by the spin-orbit coupling. This refers to the modified energy levels in an atom when the electron’s motion is under the influence on the magnetic field generated by the nucleus. Strong coupling may be intrinsic to doped semiconductors. The proposal has triggered intense investigation of the phenomenon, with first experimental observations of the spin Hall effect seen in n-doped semiconductors and two-dimensional hole gases.

Quantum spins don’t really look like the depiction above, which is meant to showcase a fact that particles like electrons do have an intrinsic angular momentum nonetheless. Credit: Karthik / Ed Publica

For more than a decade, studies concerning the spin current and its application to novel spintronics (or spin electronics) have received plethora of attention. This is with regard to efficiently generating, manipulating and detecting spin accumulation in a sample material. Some progress has also occurred from the device fabrication perspective via techniques such as spin injection, among others.

A major advantage in dealing with the spin current lies in the non-dissipative (or very less dissipation) nature which arises owing to the time reversal invariance of the spin current. This presents a non-dissipative scenario (unlike the dissipative effects seen with charged currents), thus making it quite advantageous for spin transport phenomena.

Furthermore, a quantized version of the spin Hall effect exists, with mercury telluride and cadmium telluride quantum well superlattices, showcasing this effect. In 2005, a quantum treatment was proposed by Charles Kane and Eugene Mele, in the form of a tight binding toy model of electrons operating in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice.

In fact, the ‘wonder material’ graphene, which is a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice constituting carbon atoms, does satisfy some key requirements for the quantum spin Hall effect. However, it lacks a large spin-orbit coupling among other requirements.

Nonetheless, graphene’s ability to entertain the quantum spin Hall effect, makes it a prospective candidate to find applications in next-generation spintronic devices.

Space & Physics

Physicists Capture ‘Wakes’ Left by Quarks in the Universe’s First Liquid

Scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider have observed, for the first time, fluid-like wakes created by quarks moving through quark–gluon plasma, offering direct evidence that the universe’s earliest matter behaved like a liquid rather than a cloud of free particles.

Physicists working at the CERN(The European Organization for Nuclear Research) have reported the first direct experimental evidence that quark–gluon plasma—the primordial matter that filled the universe moments after the Big Bang—behaves like a true liquid.

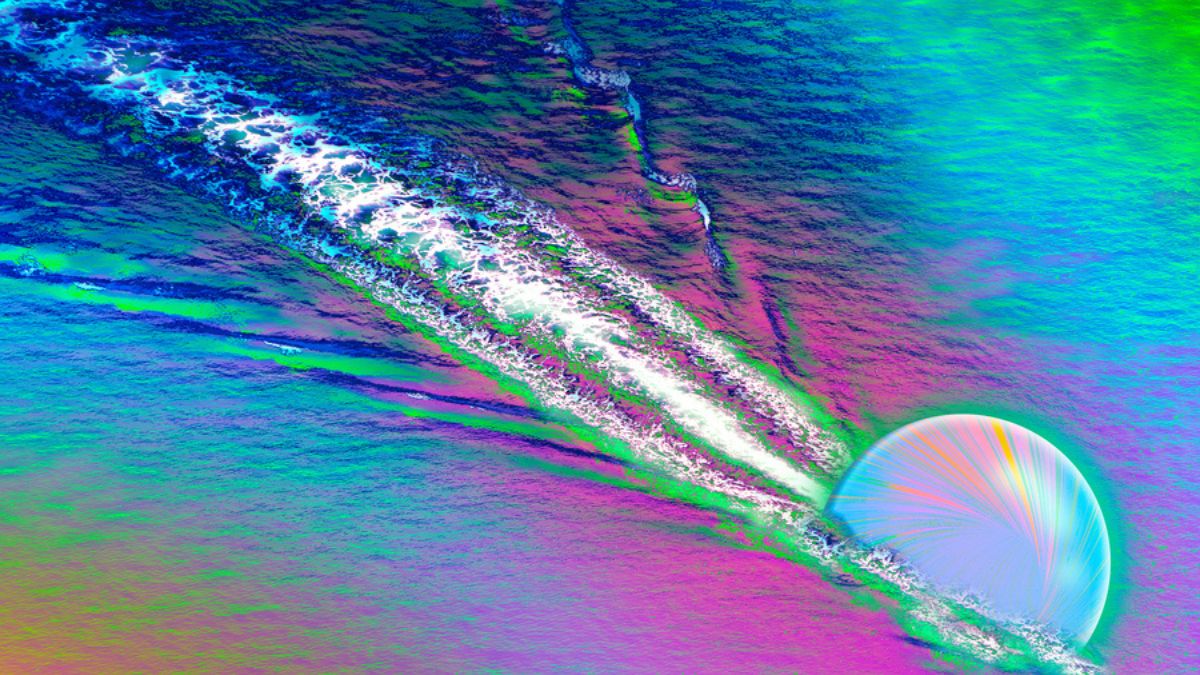

Using heavy-ion collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, researchers recreated the extreme conditions of the early universe and observed that quarks moving through this plasma generate wake-like patterns, similar to ripples trailing a duck across water.

The study, led by physicists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, shows that the quark–gluon plasma responds collectively, flowing and splashing rather than scattering randomly.

“It has been a long debate in our field, on whether the plasma should respond to a quark,” said Yen-Jie Lee in a media statement. “Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark, and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup.”

Quark–gluon plasma is believed to be the first liquid to have existed in the universe and the hottest ever observed, reaching temperatures of several trillion degrees Celsius. It is also considered a near-perfect liquid, flowing with almost no resistance.

To isolate the wake produced by a single quark, the team developed a new experimental technique. Instead of tracking pairs of quarks and antiquarks—whose effects can overlap—they identified rare collision events that produced a single quark traveling in the opposite direction of a Z boson. Because a Z boson interacts weakly with its surroundings, it acts as a clean marker, allowing scientists to attribute any observed plasma ripples solely to the quark.

“We have figured out a new technique that allows us to see the effects of a single quark in the QGP, through a different pair of particles,” Lee said.

Analysing data from around 13 billion heavy-ion collisions, the researchers identified roughly 2,000 Z-boson events. In these cases, they consistently observed fluid-like swirls in the plasma opposite to the Z boson’s direction—clear signatures of quark-induced wakes.

The results align with theoretical predictions made by MIT physicist Krishna Rajagopal, whose hybrid model suggested that quarks should drag plasma along as they move through it.

“This is something that many of us have argued must be there for a good many years, and that many experiments have looked for,” Rajagopal said.

“We’ve gained the first direct evidence that the quark indeed drags more plasma with it as it travels,” Lee added. “This will enable us to study the properties and behavior of this exotic fluid in unprecedented detail.”

The research was carried out by members of the CMS Collaboration using the Compact Muon Solenoid detector at CERN. The open-access study has been published in the journal Physics Letters B.

Space & Physics

Why Jupiter Has Eight Polar Storms — and Saturn Only One: MIT Study Offers New Clues

Two giant planets, made of the same elements, display radically different storms at their poles. New research from MIT now suggests that the key to this cosmic mystery lies not in the skies, but deep inside Jupiter and Saturn themselves.

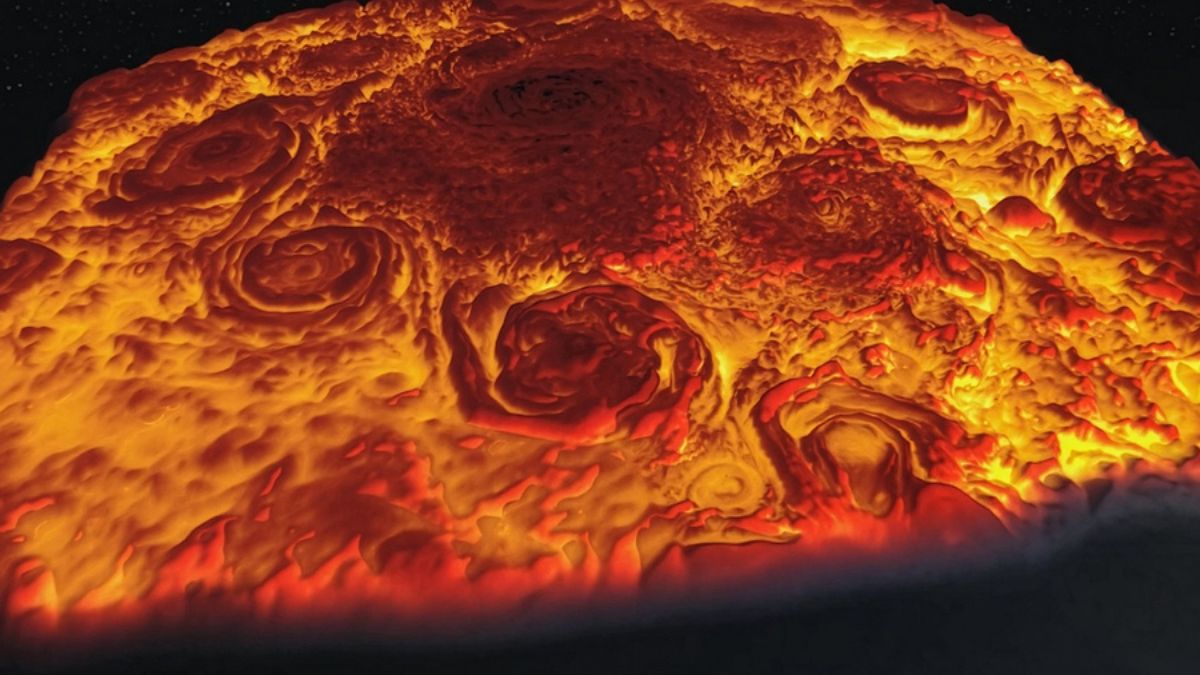

For decades, spacecraft images of Jupiter and Saturn have puzzled planetary scientists. Despite being similar in size and composition, the two gas giants display dramatically different weather systems at their poles. Jupiter hosts a striking formation: a central polar vortex encircled by eight massive storms, resembling a rotating crown. Saturn, by contrast, is capped by a single enormous cyclone, shaped like a near-perfect hexagon.

Now, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology believe they have identified a key reason behind this cosmic contrast — and the answer may lie deep beneath the planets’ cloud tops.

In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the MIT team suggests that the structure of a planet’s interior — specifically, how “soft” or “hard” the base of a vortex is — determines whether polar storms merge into one giant system or remain as multiple smaller vortices.

“Our study shows that, depending on the interior properties and the softness of the bottom of the vortex, this will influence the kind of fluid pattern you observe at the surface,” says study author Wanying Kang, assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) in a media release issued by the institute. “I don’t think anyone’s made this connection between the surface fluid pattern and the interior properties of these planets. One possible scenario could be that Saturn has a harder bottom than Jupiter.”

A long-standing planetary mystery

The contrast has been visible for years thanks to two landmark NASA missions. The Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, revealed a dramatic polar arrangement of swirling storms, each roughly 3,000 miles wide — nearly half the diameter of Earth. Cassini, which orbited Saturn for 13 years before its mission ended in 2017, documented the planet’s iconic hexagonal polar vortex, stretching nearly 18,000 miles across.

“People have spent a lot of time deciphering the differences between Jupiter and Saturn,” says Jiaru Shi, the study’s first author and an MIT graduate student. “The planets are about the same size and are both made mostly of hydrogen and helium. It’s unclear why their polar vortices are so different.”

Simulating storms on gas giants

To tackle the question, the researchers turned to computer simulations. They created a two-dimensional model of atmospheric flow designed to mimic how storms might evolve on a rapidly rotating gas giant.

While real planetary vortices are three-dimensional, the team argued that Jupiter’s and Saturn’s fast spin simplifies the physics. “In a fast-rotating system, fluid motion tends to be uniform along the rotating axis,” Kang explains. “So, we were motivated by this idea that we can reduce a 3D dynamical problem to a 2D problem because the fluid pattern does not change in 3D. This makes the problem hundreds of times faster and cheaper to simulate and study.”

The model allowed the scientists to test thousands of possible planetary conditions, varying factors such as rotation rate, internal heating, planet size and — crucially — the density of material beneath the vortices. Each simulation began with random chaotic motion and tracked how storms evolved over time.

The outcomes consistently fell into two categories: either the system developed one dominant polar vortex, like Saturn, or several coexisting vortices, like Jupiter.

The decisive factor turned out to be how much a vortex could grow before being constrained by the properties of the layers beneath it.

When the lower layers were made of softer, lighter material, individual vortices could not expand indefinitely. Instead, they stabilized at smaller sizes, allowing multiple storms to coexist at the pole. This matches what scientists observe on Jupiter.

But when the simulated vortex base was denser and more rigid, vortices were able to grow larger and eventually merge. The end result was a single, planet-scale storm — remarkably similar to Saturn’s massive polar cyclone.

“This equation has been used in many contexts, including to model midlatitude cyclones on Earth,” Kang says. “We adapted the equation to the polar regions of Jupiter and Saturn.”

The findings suggest that Saturn’s interior may contain heavier elements or more condensed material than Jupiter’s, giving its atmospheric vortices a firmer foundation to build upon.

“What we see from the surface, the fluid pattern on Jupiter and Saturn, may tell us something about the interior, like how soft the bottom is,” Shi says. “And that is important because maybe beneath Saturn’s surface, the interior is more metal-enriched and has more condensable material which allows it to provide stronger stratification than Jupiter. This would add to our understanding of these gas giants.”

Reading the interiors from the skies

Planetary scientists have long struggled to infer the internal structures of gas giants, where pressures and temperatures are far beyond what can be reproduced in laboratories. This new work offers a rare bridge between visible atmospheric patterns and hidden planetary composition.

Beyond explaining two of the Solar System’s most visually striking storms, the research could shape how scientists interpret observations of distant exoplanets as well — worlds where atmospheric patterns might be the only clues to what lies within.

For now, Jupiter’s swirling crown of storms and Saturn’s solitary hexagon may be doing more than decorating the poles of two distant giants. They may be quietly revealing the deep, unseen architecture of the planets themselves.

Space & Physics

When Quantum Rules Break: How Magnetism and Superconductivity May Finally Coexist

A new theoretical breakthrough from MIT suggests that exotic quantum particles known as anyons could reconcile a long-standing paradox in physics, opening a path to an entirely new form of superconductivity.

For decades, physicists believed that superconductivity and magnetism were fundamentally incompatible. Superconductivity is fragile: even a weak magnetic field can disrupt the delicate pairing of electrons that allows electrical current to flow without resistance. Magnetism, by its very nature, should destroy superconductivity.

And yet, in the past year, two independent experiments upended this assumption.

In two different quantum materials, researchers observed something that should not have existed at all: superconductivity and magnetism appearing side by side. One experiment involved rhombohedral graphene, while another focused on the layered crystal molybdenum ditelluride (MoTe₂). The findings stunned the condensed-matter physics community and reopened a fundamental question—how is this even possible?

Now, a new theoretical study from physicists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology offers a compelling explanation. Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers propose that under the right conditions, electrons in certain magnetic materials can split into fractional quasiparticles known as anyons—and that these anyons, rather than electrons, may be responsible for superconductivity.

If confirmed, the work would introduce a completely new form of superconductivity, one that survives magnetism and is driven by exotic quantum particles instead of ordinary electrons.

“Many more experiments are needed before one can declare victory,” said Senthil Todadri, William and Emma Rogers Professor of Physics at MIT, in a media statement. “But this theory is very promising and shows that there can be new ways in which the phenomenon of superconductivity can arise.”

A Quantum Contradiction Comes Alive

Superconductivity and magnetism are collective quantum states born from the behavior of electrons. In magnets, electrons align their spins, producing a macroscopic magnetic field. In superconductors, electrons pair up into so-called Cooper pairs, allowing current to flow without energy loss.

For decades, textbooks taught that the two states repel each other. But earlier this year, that belief cracked.

At MIT, physicist Long Ju and colleagues reported superconductivity coexisting with magnetism in rhombohedral graphene—four to five stacked graphene layers arranged in a specific crystal structure.

“It was electrifying,” Todadri recalled in a media statement. “It set the place alive. And it introduced more questions as to how this could be possible.”

Soon after, another team reported a similar duality in MoTe₂. Crucially, MoTe₂ also exhibits an exotic quantum phenomenon known as the fractional quantum anomalous Hall (FQAH) effect, in which electrons behave as if they split into fractions of themselves.

Those fractional entities are anyons.

Meet the Anyons: Where “Anything Goes”

Anyons occupy a strange middle ground in the quantum world. Unlike bosons, which happily clump together, or fermions, which avoid one another, anyons follow their own rules—and exist only in two-dimensional systems.

First predicted in the 1980s and named by MIT physicist Frank Wilczek, anyons earned their name as a playful nod to their unconventional behavior: anything goes.

Decades ago, theorists speculated that anyons might be able to superconduct in magnetic environments. But because superconductivity and magnetism were believed to be mutually exclusive, the idea was largely abandoned.

The recent MoTe₂ experiments changed that calculus.

“People knew that magnetism was usually needed to get anyons to superconduct,” Todadri said in a media statement. “But superconductivity and magnetism typically do not occur together. So then they discarded the idea.”

Now, Todadri and MIT graduate student Zhengyan Darius Shi, co-author of the study, revisited the old theory—armed with new experimental clues.

Using quantum field theory, the team modeled how electrons fractionalize in MoTe₂ under FQAH conditions. Their calculations revealed that electrons can split into anyons carrying either one-third or two-thirds of an electron’s charge.

That distinction turned out to be critical.

Anyons are notoriously “frustrated” particles—quantum effects prevent them from moving freely together.

“When you have anyons in the system, what happens is each anyon may try to move, but it’s frustrated by the presence of other anyons,” Todadri explained in a media statement. “This frustration happens even if the anyons are extremely far away from each other.”

But when the system is dominated by two-thirds-charge anyons, the frustration breaks down. Under these conditions, the anyons begin to move collectively—forming a supercurrent without resistance.

“These anyons break out of their frustration and can move without friction,” Todadri said. “The amazing thing is, this is an entirely different mechanism by which a superconductor can form.”

The team also predicts a distinctive experimental signature: swirling supercurrents that spontaneously emerge in random regions of the material—unlike anything seen in conventional superconductors.

Why This Matters Beyond Physics

If experiments confirm superconducting anyons, the implications could extend far beyond fundamental physics.

Because anyons are inherently robust against environmental disturbances, they are considered prime candidates for building stable quantum bits, or qubits—the foundation of future quantum computers.

“These theoretical ideas, if they pan out, could make this dream one tiny step within reach,” Todadri said.

More broadly, the work hints at an entirely new category of matter.

“If our anyon-based explanation is what is happening in MoTe₂, it opens the door to the study of a new kind of quantum matter which may be called ‘anyonic quantum matter,’” Todadri said. “This will be a new chapter in quantum physics.”

For now, the theory awaits experimental confirmation. But one thing is already clear: a rule long thought unbreakable in quantum physics may no longer hold—and the quantum world just became a little stranger, and far more exciting.

-

Society4 weeks ago

Society4 weeks agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth3 months ago

Earth3 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society1 month ago

Society1 month agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Women In Science4 months ago

Women In Science4 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet