Space & Physics

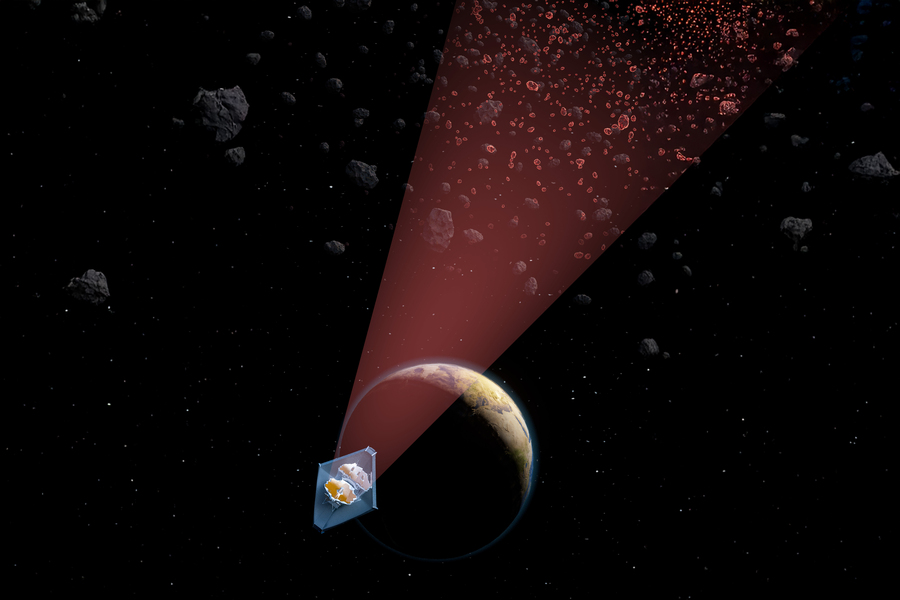

MIT team finds the smallest asteroids ever detected in the main belt

This marks the first time such small asteroids in the asteroid belt have been spotted, potentially leading to better tracking of near-Earth objects that could pose a threat

Asteroids that could potentially impact Earth vary greatly in size, from the catastrophic 10-kilometer-wide asteroid that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs to much smaller ones that strike far more frequently. Now, an international team of researchers, led by physicists at MIT, has discovered a new way to spot the smallest asteroids in our solar system’s main asteroid belt, which could provide critical insights into the origins of meteorites and planetary defense.

The team’s breakthrough approach allows astronomers to detect decameter asteroids—those just 10 meters across—much smaller than those previously detectable, which were about one kilometer in diameter. This marks the first time such small asteroids in the asteroid belt have been spotted, potentially leading to better tracking of near-Earth objects that could pose a threat.

“We have been able to detect near-Earth objects down to 10 meters in size when they are really close to Earth,” said lead author Artem Burdanov, a research scientist at MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. “We now have a way of spotting these small asteroids when they are much farther away, so we can do more precise orbital tracking, which is key for planetary defense.”

The team used their innovative method to detect over 100 new decameter asteroids, ranging from the size of a bus to several stadiums wide. These are the smallest asteroids ever found in the main asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter, where millions of asteroids orbit.

The findings, published today in Nature, have the potential to improve asteroid tracking efforts, which are critical for understanding the risk of future impacts. Scientists hope that the method could be applied to identify asteroids that may one day approach Earth.

The research team, which includes MIT planetary science professors Julien de Wit and Richard Binzel, as well as collaborators from the University of Liege, Charles University, and the European Space Agency, among others, utilized the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) for their discovery. JWST’s sensitivity to infrared light made it an ideal tool for detecting the faint infrared emissions of asteroids, which are far brighter at these wavelengths than in visible light.

The team’s approach also relied on an imaging technique called “shift and stack,” which involves aligning multiple images of the same field of view to highlight faint objects like asteroids. This technique was originally developed for exoplanet research but was adapted for asteroid detection.

The researchers believe that these new findings will help improve our understanding of asteroid population

By processing over 10,000 images of the TRAPPIST-1 system—collected to study the planets in that distant star system—the researchers identified eight known asteroids and an additional 138 new ones. These newly discovered asteroids are the smallest main belt asteroids ever detected, with diameters as small as 10 meters.

“This is a totally new, unexplored space we are entering, thanks to modern technologies,” Burdanov said. “It’s a good example of what we can do as a field when we look at the data differently. Sometimes there’s a big payoff, and this is one of them.”

The researchers believe that these new findings will help improve our understanding of asteroid populations, including the many small objects that result from collisions among larger asteroids. Miroslav Broz, a co-author from Charles University in Prague, emphasized the importance of studying these decameter asteroids to model the creation of asteroid families formed from larger, kilometer-sized collisions.

De Wit, a co-author, highlighted the significance of the discovery: “We thought we would just detect a few new objects, but we detected so many more than expected, especially small ones. It is a sign that we are probing a new population regime, where many more small objects are formed through cascades of collisions.”

(With inputs from MIT)

Space & Physics

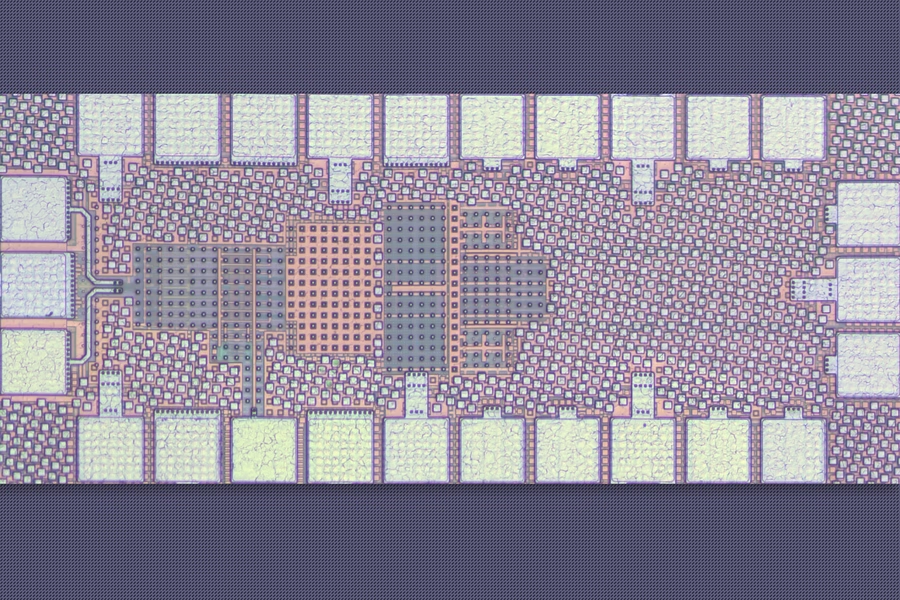

MIT unveils an ultra-efficient 5G receiver that may supercharge future smart devices

A key innovation lies in the chip’s clever use of a phenomenon called the Miller effect, which allows small capacitors to perform like larger ones

A team of MIT researchers has developed a groundbreaking wireless receiver that could transform the future of Internet of Things (IoT) devices by dramatically improving energy efficiency and resilience to signal interference.

Designed for use in compact, battery-powered smart gadgets—like health monitors, environmental sensors, and industrial trackers—the new chip consumes less than a milliwatt of power and is roughly 30 times more resistant to certain types of interference than conventional receivers.

“This receiver could help expand the capabilities of IoT gadgets,” said Soroush Araei, an electrical engineering graduate student at MIT and lead author of the study, in a media statement. “Devices could become smaller, last longer on a battery, and work more reliably in crowded wireless environments like factory floors or smart cities.”

The chip, recently unveiled at the IEEE Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium, stands out for its novel use of passive filtering and ultra-small capacitors controlled by tiny switches. These switches require far less power than those typically found in existing IoT receivers.

A key innovation lies in the chip’s clever use of a phenomenon called the Miller effect, which allows small capacitors to perform like larger ones. This means the receiver achieves necessary filtering without relying on bulky components, keeping the circuit size under 0.05 square millimeters.

Traditional IoT receivers rely on fixed-frequency filters to block interference, but next-generation 5G-compatible devices need to operate across wider frequency ranges. The MIT design meets this demand using an innovative on-chip switch-capacitor network that blocks unwanted harmonic interference early in the signal chain—before it gets amplified and digitized.

Another critical breakthrough is a technique called bootstrap clocking, which ensures the miniature switches operate correctly even at a low power supply of just 0.6 volts. This helps maintain reliability without adding complex circuitry or draining battery life.

The chip’s minimalist design—using fewer and smaller components—also reduces signal leakage and manufacturing costs, making it well-suited for mass production.

Looking ahead, the MIT team is exploring ways to run the receiver without any dedicated power source—possibly by harvesting ambient energy from nearby Wi-Fi or Bluetooth signals.

The research was conducted by Araei alongside Mohammad Barzgari, Haibo Yang, and senior author Professor Negar Reiskarimian of MIT’s Microsystems Technology Laboratories.

Society

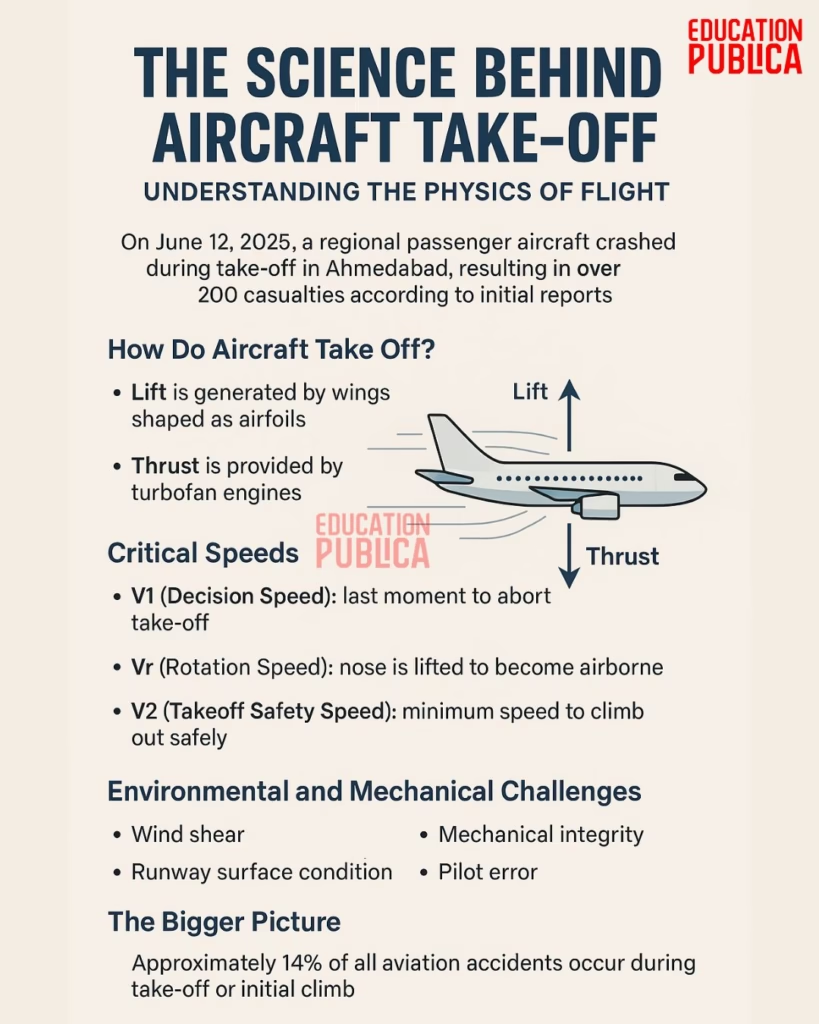

Ahmedabad Plane Crash: The Science Behind Aircraft Take-Off -Understanding the Physics of Flight

Take-off is one of the most critical phases of flight, relying on the precise orchestration of aerodynamics, propulsion, and control systems. Here’s how it works:

On June 12, 2025, a tragic aviation accident struck Ahmedabad, India when a regional passenger aircraft, Air India flight A1-171, crashed during take-off at Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport. According to preliminary reports, the incident resulted in over 200 confirmed casualties, including both passengers and crew members, and several others are critically injured. The aviation community and scientific world now turn their eyes not just toward the cause but also toward understanding the complex science behind what should have been a routine take-off.

How Do Aircraft Take Off?

Take-off is one of the most critical phases of flight, relying on the precise orchestration of aerodynamics, propulsion, and control systems. Here’s how it works:

1. Lift and Thrust

To leave the ground, an aircraft must generate lift, a force that counters gravity. This is achieved through the unique shape of the wing, called an airfoil, which creates a pressure difference — higher pressure under the wing and lower pressure above — according to Bernoulli’s Principle and Newton’s Third Law.

Simultaneously, engines provide thrust, propelling the aircraft forward. Most commercial jets use turbofan engines, which accelerate air through turbines to generate power.

2. Critical Speeds

Before takeoff, pilots calculate critical speeds:

- V1 (Decision Speed): The last moment a takeoff can be safely aborted.

- Vr (Rotation Speed): The speed at which the pilot begins to lift the nose.

- V2 (Takeoff Safety Speed): The speed needed to climb safely even if one engine fails.

If anything disrupts this process — like bird strikes, engine failure, or runway obstructions — the results can be catastrophic.

Environmental and Mechanical Challenges

Factors like wind shear, runway surface condition, mechanical integrity, or pilot error can interfere with safe take-off. Investigators will be analyzing these very aspects in the Ahmedabad case.

The Bigger Picture

Take-off accounts for a small fraction of total flight time but is disproportionately associated with accidents — approximately 14% of all aviation accidents occur during take-off or initial climb.

Space & Physics

MIT claims breakthrough in simulating physics of squishy, elastic materials

In a series of experiments, the new solver demonstrated its ability to simulate a diverse array of elastic behaviors, ranging from bouncing geometric shapes to soft, squishy characters

Researchers at MIT claim to have unveiled a novel physics-based simulation method that significantly improves stability and accuracy when modeling elastic materials — a key development for industries spanning animation, engineering, and digital fabrication.

In a series of experiments, the new solver demonstrated its ability to simulate a diverse array of elastic behaviors, ranging from bouncing geometric shapes to soft, squishy characters. Crucially, it maintained important physical properties and remained stable over long periods of time — an area where many existing methods falter.

Other simulation techniques frequently struggled in tests: some became unstable and caused erratic behavior, while others introduced excessive damping that distorted the motion. In contrast, the new method preserved elasticity without compromising reliability.

“Because our method demonstrates more stability, it can give animators more reliability and confidence when simulating anything elastic, whether it’s something from the real world or even something completely imaginary,” Leticia Mattos Da Silva, a graduate student at MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, said in a media statement.

Their study, though not yet peer-reviewed or published, will be presented at the August proceedings of the SIGGRAPH conference in Vancouver, Canada.

While the solver does not prioritize speed as aggressively as some tools, it avoids the accuracy and robustness trade-offs often associated with faster methods. It also sidesteps the complexity of nonlinear solvers, which are commonly used in physics-based approaches but are often sensitive and prone to failure.

Looking ahead, the research team aims to reduce computational costs and broaden the solver’s applications. One promising direction is in engineering and fabrication, where accurate elastic simulations could enhance the design of real-world products such as garments, medical devices, and toys.

“We were able to revive an old class of integrators in our work. My guess is there are other examples where researchers can revisit a problem to find a hidden convexity structure that could offer a lot of advantages,” Mattos Da Silva added.

The study opens new possibilities not only for digital content creation but also for practical design fields that rely on predictive simulations of flexible materials.

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoStarliner crew challenge rhetoric, says they were never “stranded”

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoCould dark energy be a trick played by time?

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoHow IIT Kanpur is Paving the Way for a Solar-Powered Future in India’s Energy Transition

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoSunita Williams aged less in space due to time dilation

-

Learning & Teaching4 months ago

Learning & Teaching4 months agoCanine Cognitive Abilities: Memory, Intelligence, and Human Interaction

-

Earth2 months ago

Earth2 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Women In Science3 months ago

Women In Science3 months agoNeena Gupta: Shaping the Future of Algebraic Geometry

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoSustainable Farming: The Microgreens Model from Kerala, South India