Society

As Oppenheimer wins the Oscars, here is an epiphany

We can’t unmix science from politics. They’re intertwined.

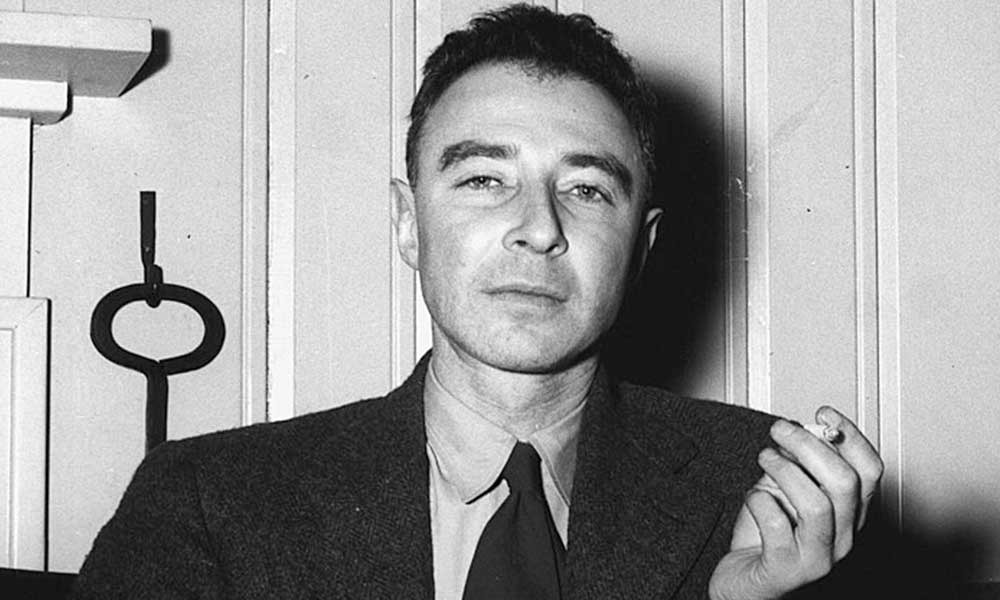

Earlier today, Christopher Nolan’s much acclaimed film, Oppenheimer (2023), won 7 awards at the Oscars – including Best Picture, Actor, Supporting Actor, Score, Cinematography, Editing and Director.

And what better moment can there be to discuss threats and fears about the wildest creations of nuclear physics?

Oppenheimer made some seminal contributions in quantum mechanics and in black hole physics. He brought ‘quantum physics to the US’. However, Oppenheimer was also a public intellectual, who dabbled with left wing politics in his younger days. He rose to national prominence after he led Los Alamos National Laboratory as Director, in an effort that saw the US develop and wield nuclear weapons. He forever became known as the ‘father of the atom bomb’, a label that didn’t do anything to stop him spiraling into depression, as he saw his legacy tainted with death and destruction.

Nolan’s movie was a biopic, based on authors Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird’s Pulitzer Prize winning biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In a scene that shakes you to the core, Oppenheimer (played by Cilian Murphy) imagines seeing the horrific effects of a nuclear bombing on humans. A corpse flash fried, that crumbles upon the lightest touch. People mourning deaths of their loved ones, people vaporized leaving no traces behind. Others left alive with burns, and others vomiting irrecoverably from radiation sickness. Just imagine this is a time when people didn’t even really know what radiation sickness was all about. How many people would’ve dabbled with radioactivity? And now all it takes is one bomb to exact such a devastating toll on human life.

We wonder – who’s accountable for all this? The maker or the master? Or both?

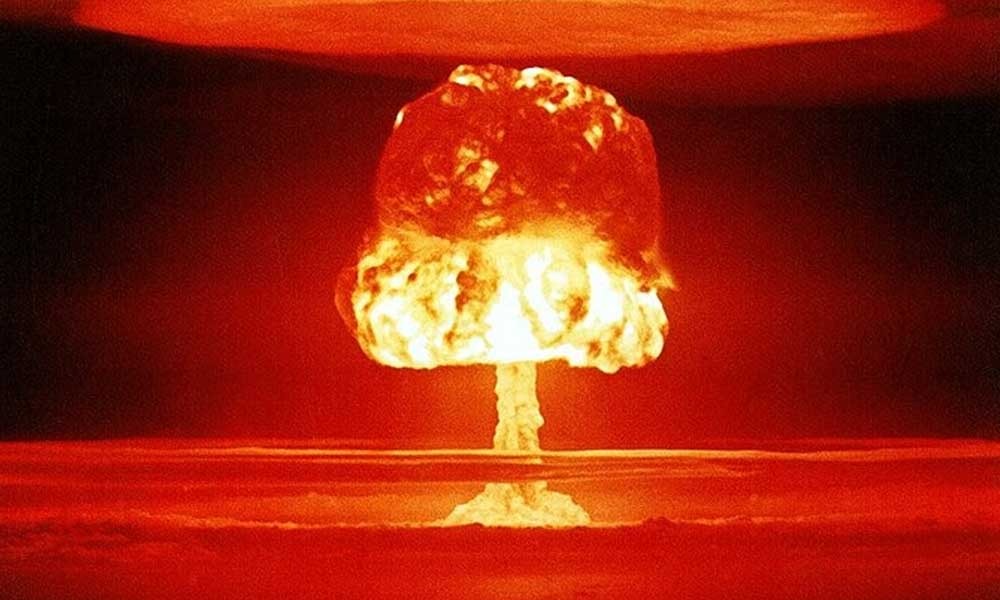

Image of the nuclear detonation in US’ Castle Romeo test in 1954. Credit: United States Department of Energy

Oppenheimer lends an opportunity to assess scientists by holding them at the same pedestal as we do with politicians – especially when they’re prone to serious misjudgment. Oppenheimer thought the best way to demonstrate deterrence was to demonstrate the weapon’s capability. He assumed it wouldn’t proliferate, if they were demonstrated with an attack. ‘They (people) won’t fear it, unless they understand it, and they won’t understand it, until they’ve used it,’ as Cilian Murphy said in the movie. And they did use it.

Did people fear it? Yes and no. On one end there’s the physical damage of it all. But on the other end there came the political chain reaction – with nuclear arsenal stockpiling to record highs during the Cold War. There are still enough nukes around the world to end human civilization many times over.

Frankenstein died, but the monster lives on.

It’s an age-old claim now, as old as the Trinity test itself that it was impossible to stop the nuclear bomb developments. Somebody else or the other would have made it. This is sadly true. However, when we think of science itself – as Isidor Rabbi in the movie (played by David Krumholtz) said, ‘I don’t wish the culmination of three centuries of physics to be a weapon of mass destruction.’ Is science really divorced from political realities? Sure, a nuclear chain reaction isn’t dependent on policy. Of course, but launching an initiative to trigger one surely is. Leo Szilard’s letter sent to US President Theodore Roosevelt, signed off by Albert Einstein, discussed the feasibility of the US wielding a nuclear weapon to deter the Germans. That’s as straightforward as it can get.

It reflects policy change, when Nobel Peace Prize winner and nuclear physicist, Joseph Rotblat claimed General Leslie Groves (who oversaw the Manhattan Project) stating that it was the Soviets who the US seeked to intimidate with the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks. And when the Soviets surprised the US by revealing their own sophisticated nuclear program with a growing arsenal, the world locked up in a race for their own weapons. There was a total snafu.

Although Nolan used Sherwin and Bird’s source material as the inspiration for Oppenheimer to be depicted as a Prometheus, he’s also undoubtedly similar to Frankenstein as well.

Frankenstein died, but the monster lives on. What can we learn from all of this? Well, science and society are so intertwined that they both shape each other. The other is we may need to figure out who’s accountable for technological and scientific innovations.

Innovation may not really be unstoppable, if there’s collective action and we decide for ourselves what the world ought to be. Perhaps nuclear holocaust isn’t fictional, but at least we can do something for innovations in our society today.

“I have been interested to talk to some of the leading researchers in the AI field, and hear from them that they view this as their ‘Oppenheimer moment’,” said Nolan in an interview to The Guardian. AI can provide jobs as much as it takes away them, and that’s the challenge of our times. “And they’re clearly looking to his story for some kind of guidance … as a cautionary tale in terms of what it says about the responsibility of somebody who’s putting this technology to the world, and what their responsibilities would be in terms of unintended consequences.”

We’d rather be wise and learn from history, than repeat it. May that lead to an era of responsible innovation.

Technology

From Tehran Rooftops To Orbit: How Elon Musk Is Reshaping Who Controls The Internet

How Starlink turned the sky into a battleground for digital power — and why one private network now challenges the sovereignty of states

On a rooftop in northern Tehran, long after midnight, a young engineering student adjusts a flat white dish toward the sky. The city around him is digitally dark—mobile data throttled, social media blocked, foreign websites unreachable. Yet inside his apartment, a laptop screen glows with Telegram messages, BBC livestreams, and uncensored access to the outside world.

Scenes like this have appeared repeatedly in footage from Iran’s unrest broadcast by international news channels.

But there’s a catch. The connection does not travel through Iranian cables or telecom towers. It comes from space.

Above him, hundreds of kilometres overhead, a small cluster of satellites belonging to Elon Musk’s Starlink network relays his data through the vacuum of orbit, bypassing the state entirely.

For governments built on control of information, this is no longer a technical inconvenience. It is a political nightmare. The image is quietly extraordinary. Not because of the technology — that story is already familiar — but because of what it represents: a private satellite network, owned by a US billionaire, now functioning as a parallel communications system inside a sovereign state that has deliberately tried to shut its citizens offline.

The Rise of an Unstoppable Network

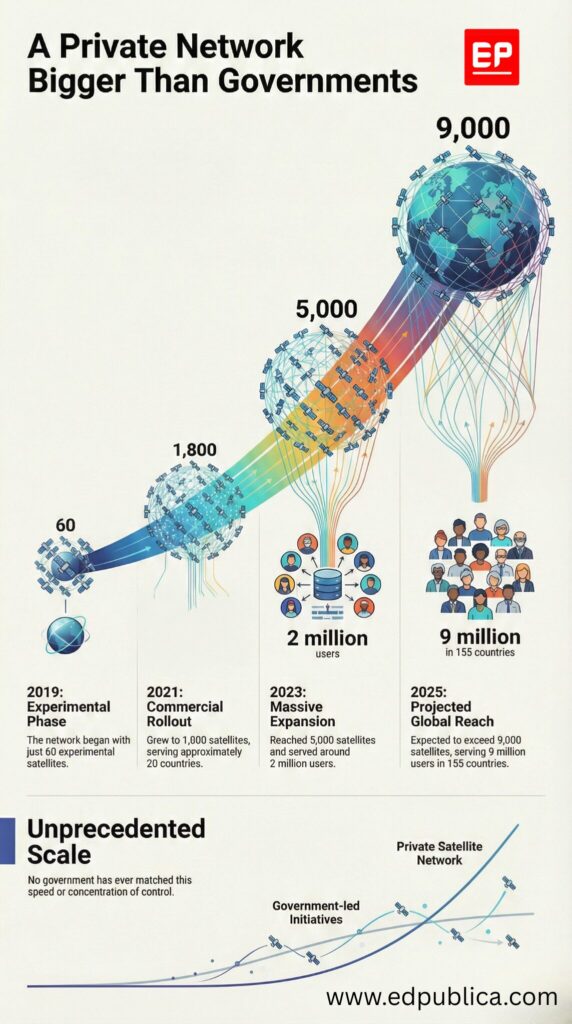

Starlink, operated by Musk’s aerospace company SpaceX, has quietly become the most ambitious communications infrastructure ever built by a private individual.

As of late 2025, more than 9,000 Starlink satellites orbit Earth in low Earth orbit (LEO) (SpaceX / industry trackers, 2025). According to a report in Business Insider, the network serves over 9 million active users globally, and Starlink now operates in more than 155 countries and territories (Starlink coverage data, 2025).

It is the largest satellite constellation in human history, dwarfing every government system combined.

This is not merely a technology story. It is a power story.

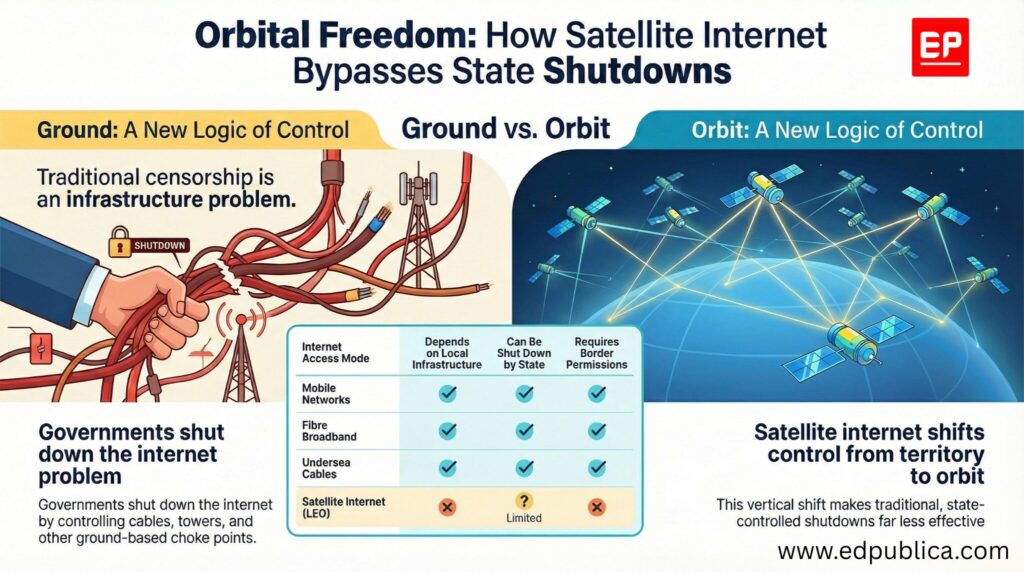

Unlike traditional internet infrastructure — fibre cables, mobile towers, undersea routes — Starlink’s backbone exists in space. It does not cross borders. It does not require landing rights in the conventional sense. And, increasingly, it does not ask permission.

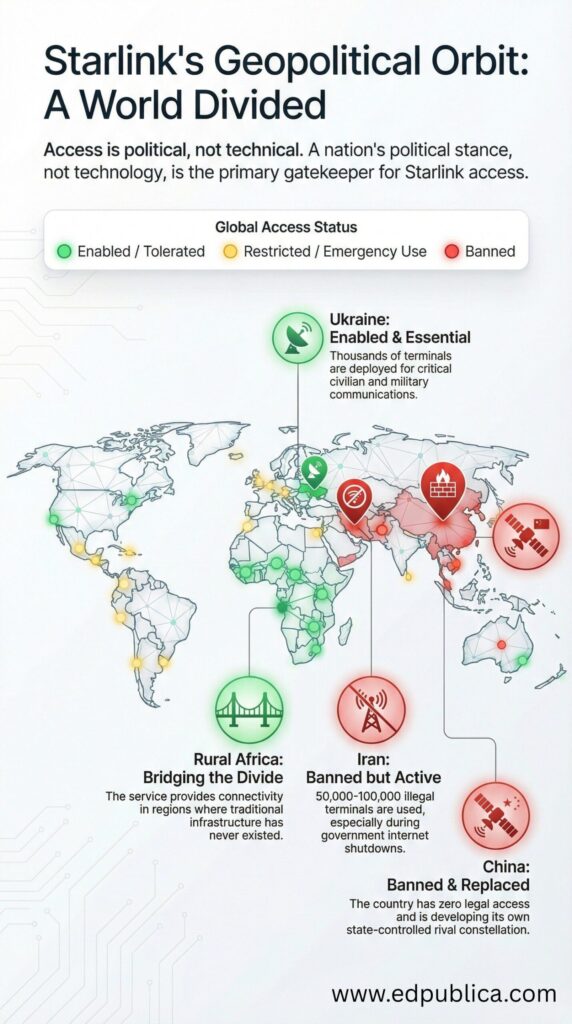

Iran: When the Sky Replaced the State

During successive waves of anti-government protests in Iran, authorities imposed sweeping internet shutdowns: mobile networks crippled, platforms blocked, bandwidth throttled to near zero. These tactics, used repeatedly since 2019, were designed to isolate protesters from each other and from the outside world.

They did not fully anticipate space-based internet.

By late 2024 and 2025, Starlink terminals had begun appearing clandestinely across Iranian cities, smuggled through borders or carried in by diaspora networks. Possession is illegal. Penalties are severe. Yet the demand has grown.

Because the network operates without local infrastructure, users can communicate with foreign media, upload protest footage in real time, coordinate securely beyond state surveillance, and maintain access even during nationwide blackouts.

The numbers are necessarily imprecise, but multiple independent estimates provide a sense of scale. Analysts at BNE IntelliNews estimated over 30,000 active Starlink users inside Iran by 2025.

Iranian activist networks suggest the number of physical terminals may be between 50,000 and 100,000, many shared across neighbourhoods. Earlier acknowledgements from Elon Musk confirmed that SpaceX had activated service coverage over Iran despite the lack of formal licensing.

This is what alarms governments most: the state no longer controls the kill switch.

Ukraine: When One Man Could Switch It Off

The power — and danger — of this new infrastructure became even clearer in Ukraine.

After Russia’s 2022 invasion, Starlink terminals were shipped in by the thousands to keep Ukrainian communications alive. Hospitals, emergency services, journalists, and frontline military units all relied on it. For a time, Starlink was celebrated as a technological shield for democracy.

Then came the uncomfortable reality.

Investigative reporting later revealed that Elon Musk personally intervened in decisions about where Starlink would and would not operate. In at least one documented case, coverage was restricted near Crimea, reportedly to prevent Ukrainian drone operations against Russian naval assets.

The implications were stark: A private individual, accountable to no electorate, had the power to influence the operational battlefield of a sovereign war. Governments noticed.

Digital Sovereignty in the Age of Orbit

For decades, states have understood sovereignty to include control of national telecom infrastructure, regulation of internet providers, the legal authority to impose shutdowns, the power to filter, censor, and surveil.

Starlink disrupts all of it.

Because, the satellites are in space, outside national jurisdiction. Access can be activated remotely by SpaceX, and the terminals can be smuggled like USB devices. Traffic can bypass domestic data laws entirely.

In effect, Starlink represents a parallel internet — one that states cannot fully regulate, inspect, or disable without extraordinary countermeasures such as satellite jamming or physical raids.

Authoritarian regimes view this as foreign interference. Democratic governments increasingly see it as a strategic vulnerability. Either way, the monopoly problem is the same: A single corporate network, controlled by one individual, increasingly functions as critical global infrastructure.

How the Technology Actually Works

The power of Starlink lies in its architecture. Traditional internet depends on fibre-optic cables across cities and oceans, local internet exchanges, mobile towers and ground stations, and centralised chokepoints.

Starlink bypasses most of this. Instead, it uses thousands of LEO satellites orbiting at ~550 km altitude, user terminals (“dishes”) that automatically track satellites overhead, inter-satellite laser links, allowing data to travel from satellite to satellite in space, and a limited number of ground gateways connecting the system to the wider internet.

This design creates resilience: No single tower to shut down, no local ISP to regulate, and no fibre line to cut.

For protesters, journalists, and dissidents, this is transformative. For governments, it is destabilising.

A Private Citizen vs the Rules of the Internet

The global internet was built around multistakeholder governance: National regulators, international bodies like the ITU, treaties governing spectrum use, and complex norms around cross-border infrastructure.

Starlink bypasses much of this through sheer technical dominance, and it has become a company that: owns the rockets, owns the satellites, owns the terminals, controls activation, controls pricing, controls coverage zones… effectively controls a layer of global communication.

This is why policymakers now speak openly of “digital sovereignty at risk”. It is no longer only China’s Great Firewall or Iran’s censorship model under scrutiny. It is the idea that global connectivity itself might be increasingly privatised, personalised, and politically unpredictable.

The Unanswered Question

Starlink undeniably delivers real benefits, it offers connectivity in disaster zones, internet access in rural Africa, emergency communications in war, educational access where infrastructure never existed.

But it also raises an uncomfortable, unresolved question: Should any individual — however visionary, however innovative — hold this much power over who gets access to the global flow of information?

Today, a protester in Tehran can speak to the world because Elon Musk chooses to allow it.

Tomorrow, that access could disappear just as easily — with a policy change, a commercial decision, or a geopolitical calculation.The sky has become infrastructure. Infrastructure has become power. And power, increasingly, belongs not to states — but to a handful of corporations.

There is another layer to this power calculus — and it is economic. While Starlink has been quietly enabled over countries such as Iran without formal approval, China remains a conspicuous exception. The reason is less technical than commercial. Elon Musk’s wider business empire, particularly Tesla, is deeply entangled with China’s economy. Shanghai hosts Tesla’s largest manufacturing facility in the world, responsible for more than half of the company’s global vehicle output, and Chinese consumers form one of Tesla’s most critical markets.

Chinese authorities, in turn, have made clear their hostility to uncontrolled foreign satellite internet, viewing it as a threat to state censorship and information control. Beijing has banned Starlink terminals, restricted their military use, and invested heavily in its own rival satellite constellation. For Musk, activating Starlink over China would almost certainly provoke regulatory retaliation that could jeopardise Tesla’s operations, supply chains, and market access. The result is an uncomfortable contradiction: the same technology framed as a tool of freedom in Iran or Ukraine is conspicuously absent over China — a reminder that even a supposedly borderless internet still bends to the gravitational pull of corporate interests and geopolitical power.

Climate

Ancient lake sediments suggest India’s monsoon was far stronger during medieval warm period

New palaeoclimate evidence from central India suggests that the Indian Summer Monsoon was significantly stronger during the medieval warm period than previously believed

India’s monsoon history may be more intense than previously assumed, according to new palaeoclimate evidence recovered from lake sediments in central India. Scientists analysing microscopic pollen preserved in Raja Rani Lake, in present-day Korba district of Chhattisgarh, have found signs of unusually strong and sustained Indian Summer Monsoon rainfall between about 1,060 and 1,725 CE.

The findings come from researchers at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology, and are based on a detailed reconstruction of vegetation and climate in India’s Core Monsoon Zone (CMZ)—the region that receives nearly 90 percent of the country’s annual rainfall from the Indian Summer Monsoon.

Reading climate history from pollen

Researchers extracted a 40-centimetre-long sediment core from Raja Rani Lake. These layers of mud record environmental changes spanning roughly the last 2,500 years. Embedded within them are fossil pollen grains released by plants that once grew around the lake.

By identifying and counting these grains—a method known as palynology—the team reconstructed past vegetation patterns and inferred climate conditions. Forest species that thrive in warm, humid environments point to periods of strong rainfall, while grasses and herbs are indicators of relatively drier phases.

According to the scientists, the pollen record from the medieval period shows a clear dominance of moist and dry tropical deciduous forest taxa. This points to a persistently warm and humid climate in central India, driven by a strong monsoon system, with no evidence of prolonged dry spells within the CMZ during that time.

Medieval Climate Anomaly linked to stronger monsoon

The period of intensified rainfall coincides with the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA), a globally recognised warm phase dated to roughly 1,060–1,725 CE. The study suggests that the strengthened Indian Summer Monsoon during this interval was shaped by a combination of global and regional drivers.

In a media statement, the researchers noted that La Niña–like conditions—typically associated with stronger Indian monsoons—may have prevailed during the MCA. Other contributing factors likely included a northward shift of the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone, positive temperature anomalies, higher sunspot numbers and increased solar activity.

Why this matters today

The Core Monsoon Zone is particularly sensitive to fluctuations in the Indian Summer Monsoon, making it a key region for understanding long-term hydroclimatic variability during the Late Holocene (also known as the Meghalayan Age). Scientists say insights from this period are crucial for contextualising present-day monsoon behaviour under ongoing climate change.

The BSIP team said high-resolution palaeoclimate records such as these can strengthen climate models used to simulate future rainfall patterns. Beyond academic interest, the findings have implications for water management, agriculture and climate-resilient policy planning in monsoon-dependent regions.

By revealing that central India once experienced a more intense and sustained monsoon than previously recognised, the study adds a deeper historical perspective to debates on how the Indian monsoon may respond to current and future warming.

Society

Reliance to build India’s largest AI-ready data centre, positions Gujarat as global AI hub

As part of making Gujarat India’s artificial intelligence pioneer, in Jamnagar we are building India’s largest AI-ready data centre: Mukesh Ambani

Reliance Industries Limited, India’s largest business group, has announced plans to build the country’s largest artificial intelligence–ready data centre in Jamnagar, a coastal industrial city in the western Indian state of Gujarat, as part of a broader push to expand access to AI technologies at population scale.

The announcement was made by Mukesh Ambani, chairman and managing director of Reliance Industries, during the Vibrant Gujarat Regional Conference for the Kutch and Saurashtra region, a government-led investment and development forum focused on regional economic growth.

Ambani said the Jamnagar facility is being developed with a single objective: “Affordable AI for every Indian.” He positioned the project as a foundational investment in India’s digital infrastructure, aimed at enabling large-scale adoption of artificial intelligence across sectors including industry, services, education and public administration.

“As part of making Gujarat India’s artificial intelligence pioneer, in Jamnagar we are building India’s largest AI-ready data centre,” Ambani said, adding that the facility is intended to support widespread access to AI tools for individuals, enterprises and institutions.

Reliance also announced that its digital arm, Jio, will launch a “people-first intelligence platform,” designed to deliver AI services in multiple languages and across consumer devices. According to Ambani, the platform is being built in India for both domestic and international users, with a focus on everyday productivity and digital inclusion.

The AI initiative forms part of Reliance’s broader commitment to invest approximately Rs 7 trillion (about USD 85 billion) in Gujarat over the next five years. The company said the investments are expected to generate large-scale employment while positioning the region as a hub for emerging technologies.

The Jamnagar AI data centre is being developed alongside what Reliance describes as the world’s largest integrated clean energy manufacturing ecosystem, encompassing solar power, battery storage, green hydrogen and advanced materials. Ambani said the city, historically known as a major hub for oil refining and petrochemicals, is being re-engineered as a centre for next-generation energy and digital technologies.

The announcements were made in the presence of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Gujarat Chief Minister Bhupendra Patel, underscoring the alignment between public policy and private investment in India’s long-term technology and infrastructure strategy.

-

Society1 week ago

Society1 week agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoNew double-slit experiment proves Einstein’s predictions were off the mark

-

Earth2 months ago

Earth2 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP302 months ago

COP302 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

COP302 months ago

COP302 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Women In Science3 months ago

Women In Science3 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Space & Physics1 month ago

Space & Physics1 month agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date