Society

Why Kerala Has Struggled to Replicate Perinjanam’s Solar Success

In Perinjanam, a small coastal village in Kerala, rooftop solar panels have transformed hundreds of households—slashing electricity bills and proving the potential of community-driven energy. Yet across Kerala, India’s most literate state, similar projects remain rare, revealing the gap between local innovation and statewide adoption. Here is how it can happen.

On a humid afternoon in Perinjanam, a coastal panchayat in Thrissur district of the South Indian state Kerala, Susheela leads me into her kitchen and points upstairs to the metal roof. The small array of solar panels there has changed the family’s daily expenses. “Before 2016, our electricity bill was over Rs 1,000 every month. After that, it rarely crosses Rs 200,” she says, folding her hands as if to show how the burden has lifted. “Installing solar panels on the roof has been undoubtedly beneficial. We’ve seen clear savings on our bills,” Susheela says.

Perinjanorjam (Perinjanam Energy), the village’s community-driven rooftop solar initiative, now powers more than a thousand households like Susheela’s and has drawn attention across India. In 2016, the panchayat embarked on what was then an audacious experiment—combining government subsidies, cooperative-bank lending, and local mobilization to make an energy self-reliant village. The results were undeniable on the ground. But the very success that made Perinjanam a poster child has not translated into a replicable model across Kerala. Nine years since its launch, and three years after high-profile endorsements and study visits, other panchayats still hesitate. Why?

The Perinjanam solar project, driven by the collective efforts of local institutions and residents, is celebrated as a model for other panchayats. For a state like Kerala, which relies heavily on electricity from outside, rooftop solar projects are crucial. By involving ordinary families, they demonstrate the strength of a decentralized approach—while also advancing India’s clean energy transition.

At COP26, India pledged 500 GW of renewable capacity by 2030. Progress has been steady, with 235.7 GW already in place, but the pace must increase. Decentralized, community-driven initiatives like Perinjanam could help bridge the gap.

What is the Perinjanam Project?

It’s an alternative electricity generation and distribution model, with participation from the public, panchayat, cooperative bank, Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB), and Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI), carried out in Perinjanam gram panchayat, Thrissur. Perinjanam, the first panchayat in India to generate 700 kW of rural solar power for itself, is a model for local energy self-sufficiency. Daytime electricity from the solar panels is used for household needs; the surplus is supplied to KSEB’s common pool grid. At night, homes rely on KSEB power. Electricity bills reflect the difference between what is exported and what is imported. If the exported and imported electricity quantities are equal, the only charge is meter rent. The heart of Perinjanam project is a consumer committee set up for project implementation.

Launched in 2016 by then-panchayat president Sachith KK with the support of then Kerala State Electricity Regulatory Commission (KSERC) chairman TM Manoharan, Perinjanam’s solar initiative was born out of their vision, as said by then consumer committee head Noorrudheen to EdPublica. “Sachith learned about SECI’s 500 kW subsidized scheme for solar in Kerala through Manoharan. The idea to use this for local benefit was decisive,” Noorrudheen says.

Through numerous meetings and awareness campaigns, ward members reached out house-to-house to educate people about solar. Since the project started soon after a major solar scam in Kerala, skepticism lingered. The initial plan was for a 500 kW project covering 250 homes, with rooftop units typically ranging from 1 to 5 kW. For Perinjanam residents, many of whom faced financial hardships, participation in the novel project required financial support. Both the panchayat and the cooperative bank (then under CPI(M) leadership) decided after much discussion to give low-interest, collateral-free loans to participants. Noorrudheen credits this bank loan as the key factor that made the Perinjanam project a success. With Manoharan as an advisor, KSEB offered full support. Households with bills above Rs 500 were targeted first. An active, proactive panchayat president engaged the cooperative bank, registered a consumer committee as a one-stop solution for project management, and worked with SECI for subsidies. Thus, Perinjanam stands out as a unique community-driven project involving multiple stakeholders—a model found nowhere else.

According to latest estimates, Perinjanam section’s monthly generation stood at 3.16 MW, now including Kaypamangalam and Mathilakam panchayats. “There are 1008 connections under the Perinjanam section. The project covers 956 houses. The remaining are shops and other institutions. Today the project reached a capacity of 4,305 kW. The total generation is 316,823 units,” says KSEB Assistant Engineer Thara.

The project can produce enough electricity in a year to meet the needs of roughly 4,000–6,000 rural households. Perinjanam has around 5,342 households, according to the last Census report, and a typical rural home in Kerala uses about 97 units per month. That means the plant’s full annual potential—roughly 5.17–6.89 million units—could supply most, if not all, of the panchayat’s households. So far, it has generated 316,823 units, already enough for about a year’s supply to 270 homes, a figure expected to grow as the system completes more annual cycles—enough to power nearly all homes in one or two wards of Perinjanam.

Why Hasn’t Perinjanam Been Replicated?

Apart from achieving energy self-sufficiency through solar power, a 2022 report revealed that the Perinjanam Solar Initiative reduced carbon emissions by 192,000 kilograms. Inspired by Perinjanam’s outcomes, 37 panchayats in Tamil Nadu decided to implement similar projects, and in 2022, a 45-member delegation from Tamil Nadu visited Perinjanam to study the model.

Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan and Finance Minister K N Balagopal had publicly urged other panchayats to adopt the Perinjanam model. However, no other panchayat has followed suit so far. Let us look at the reasons behind this.

One major reason, as often pointed out, is that the Perinjanam Solar Project was not a flagship initiative of the panchayat itself. The panchayat acted only as a facilitator, while it was the consumer committee that took the lead in implementation. The project originated from the idea of the then panchayat president, who pushed it forward, but what truly set it apart was the proactive role of the consumer committee.

The Perinjanam model is in fact the most practical and replicable model for other panchayats. What makes it unique is the structure of its consumer committee, a 14-member registered body that oversees everything—including the maintenance of solar units and overall project management. Earlier, the panchayat president himself was part of the committee. However, with a change in the elected local body, the current panchayat committee appears less interested in the project. The consumer committee members are elected annually by the beneficiaries themselves. “It is this committee system that keeps the initiative alive,” explains Noorrudheen.

Our visit to the panchayat office confirmed this impression: informally, top officials acknowledged that the panchayat functions only as a facilitator. And the response reflects their lack of interest. “For Perinjanam’s success to spread elsewhere, what is needed most is government-level intervention,” says Sachith. He recalls that Finance Minister Balagopal even mentioned Perinjanam in his budget speech, urging local bodies to adopt such initiatives. “But that is not enough,” he argues. Each year, the government issues guidelines listing ten mandatory activities/action plans for local bodies. Unless rooftop solar—implemented with people’s investment, cooperative bank support, and government subsidies—is included in that framework, and unless it becomes part of the annual project plan, real expansion will not happen. “So far, no such directive has come. That is a big reason for the failure,” Sachith adds. “If each of Kerala’s 956 panchayats installed even one megawatt, which alone would add up to 956 MW. People are willing to invest their money; cooperative banks only need to support those who cannot afford the upfront cost. It requires far less effort and expense than building new power projects. But it must be made mandatory to install 1 MW of solar energy in every Panchayat,” he insists.

Another barrier is the lack of awareness. “People do not fully understand what green energy is, nor why shifting to it is important,” says the former panchayat president. “I installed a 4 kW rooftop solar unit at my house. I own an electric scooter and even an electric car. But very few people think about how far we can run an entire household on green energy.”

There is also the issue of local body leadership. Panchayat leaders often fail to think innovatively about the possibilities before them. “We once used CSR funds to power streetlights with rooftop solar. The panchayat, which had an electricity bill of Rs 90,000(approximately $1,015.50) , reduced it by nearly Rs 30,000 ($338.50),” recalls Sachith.

For N K Sathyanathan, who was the president of the local cooperative bank during the project’s rollout, the main barrier to replication elsewhere is lack of financial support mechanisms. “When we began Perinjanam Solar, cooperative banks technically had no provision to offer loans for rooftop solar. But with the support of the then panchayat president and Manoharan from KSEB, we devised a sub-rule to make it possible,” he explains. The bank allocated Rs 1 crore for loans, offering up to Rs 50,000 per individual with minimal collateral—family members could stand as mutual guarantors, without the need for extra security. The loans were offered at low interest and had a 36-month repayment period. Over 300 households received loans in the first phase, and almost all repaid ahead of schedule, without a single default.

Sathyanathan argues that if Kerala’s many cooperative banks adopt a similar loan framework, it could unleash a revolution in rooftop solar. He recalls even Tamil Nadu officials asking him how they managed it, and he shared their model of innovative lending. “When electricity demand rises, states often turn to nuclear or hydro projects. But rooftop solar is a viable alternative. If encouraged, Kerala would never need to depend on buying electricity from other states,” he says. “The government doesn’t lose a single rupee on this model.”

Noorrudheen adds that affordable financing is crucial to expand rooftop solar to low-income households. He also stresses that consumer committees are vital: since these are long-term projects, relying on elected panchayat bodies alone is risky, because changes in leadership after elections can disrupt continuity. Instead, projects should be run by independent consumer committees, supported by the panchayat. Ensuring the availability of technical experts even after the warranty period is another key requirement.

Premlal, convener, consumer committee, thinks that the lack of interest from agencies like KSEB is also a factor. “The Perinjanam project happened due to a confluence of many factors—the vision of the then panchayat leadership, intervention by the KSEB regulatory commission chairman, Manoharan’s initiative, and crucially, cooperative bank financing. Many residents also invested from their own pockets. Unless such elements come together, replication elsewhere will remain difficult.”

“At that time, about 500 people in Perinjanam were aware of solar. It was significant that a 1 kW system could be installed for Rs 45,500 (approximately $664–$684 USD at 2016 exchange rates),” says Sachith. The project was implemented by a 14-member solar consumer committee chaired by the panchayat president, with the panchayat serving as facilitator and eligible houses enrolled. SECI sanctioned a Rs 19,500 subsidy per kW, bringing the actual cost per kW to Rs 65,000; consumers paid only Rs 45,500. The committee handled documentation, SECI coordination, and contracting, freeing consumers from hassles. Contractors were selected through competitive quotations. GPR Power Solutions (Chennai) was contracted for implementation, and the consumer committee continues to manage maintenance. Loans to the tune of Rs 1.3 crore were taken from the cooperative bank for the project.

Lives Transformed

“Rooftop units range from 1 to 5 kW, with the initial target being 500 kW; it’s presumed now to exceed 4,000 kW. Perinjanam’s success inspired others, and the project is a global model—environmentally, too, its benefits are clear. People are very satisfied,” says consumer committee convener Premlal, a fact confirmed by the EdPublica team’s field visit.

Still, people have some anxieties about new regulations. “We installed our solar unit at launch, with Manoharan’s advice. Our bills now are just Rs 130–200. But there are rumors of rule changes, and that worries us,” says Susheela, a Perinjanam homemaker. Recently, bill amounts have increased, which she and others have brought up with the committee. She adds: “We’ve never had any problem with the solar unit. When the panel broke, it was replaced free.” Susheela’s family installed a 2 kW unit via loan; the process was smooth and the amount repaid in two years.

Image by Lakshmi Narayanan/EdPublica

Rahimabi, another resident, notes that bills initially came down to Rs 250 but are now as high as Rs 1,000 again, which concerns her. Bharathan, a Gulf returnee, has a 2 kW unit and says he’s never had a maintenance issue. He worries about a possible rule requiring battery storage for units above 3 kW and says his panel may soon need replacing. His monthly bill, once Rs 900–Rs 1,000, is now just Rs 300, but he laments the low compensation from KSEB and the risk of full supply loss in a power cut.

Prajitha and Sreekanth’s family, among the first solar homes in the panchayat, added battery storage alongside their unit because of concerns about rising bills. “Earlier, my bill was Rs 900. Now, we pay only the meter rent—Rs 140. There have been no maintenance issues so far.”

Premlal also reports quick payback and additional income for higher producers, and Sathyan master, another resident, claims he got back as much as Rs 2,000 after use. One house, for instance, produces 17 units per day, and some households that both produce and consume solar energy (prosumers) have earned up to Rs 9,000 by selling power back to KSEB. At the same time, the reality is that the project has not yet reached everyone in the panchayat. “I have never heard about such a solar initiative,” says Raphael, a mason and resident of Perinjanam. Sukanya, a homemaker from Perinjanam, adds, “I had no awareness of such a project, and when I first heard about it, it seemed like something that would cost a lot of money.”

Image by Lakshmi Narayanan/EdPublica

Why Kerala Needs Rooftop Solar

According to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Kerala currently ranks 13th in the country in terms of installed renewable energy capacity. Across India, nearly 80% of newly added renewable units are solar-based. Government figures show that India has overtaken Japan to become the world’s third-largest solar producer. As of July 2025, the country’s cumulative solar capacity stands at 119.92 GW—of which 19.88 GW comes from grid-connected rooftop systems and 5.09 GW from off-grid installations. Notably, Kerala does not figure among the regions identified by the Centre as high-potential zones for renewable energy.

States like Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh have tackled the solar energy challenge by setting up vast solar farms spread across thousands of hectares. Kerala, however, does not have such an option due to its limited land availability. “But there is immense potential for rooftop solar here,” says Sreekanth, an independent researcher in the field.

According to official government reports, Kerala’s installed solar capacity stands at 1,792.34 MW. Of this, the installed rooftop solar capacity is just 24.93 MW. Data released by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) shows that the state’s total renewable energy capacity is 4,106.78 MW. This means rooftop solar contributes only 1.39% of Kerala’s total solar capacity, and just 0.61% of the overall renewable energy capacity.

Kerala has set ambitious targets: to achieve 100% renewable energy by 2040 and to become a net carbon-neutral state by 2050. The Kerala State Action Plan on Climate Change 2023–2030 (Kerala SAPCC 2.0), released by the Chief Minister, outlines several programmes and strategies designed to help the state reach these goals.

In this journey, rooftop solar projects will have a decisive role to play. Kerala now has 152,000 rooftop units (946.9 MW), a top growth record under the PM Surya Ghar programme—yet only 2 percent of its 13 million energy consumers use rooftop solar. Critics say new policies have raised fresh challenges, even as KSEB imports about 70% of its electricity from outside. Solar remains the best alternative.

Rising Challenges

Noorrudheen points out a growing concern: because of the current approach of the government and KSEB, solar power is becoming a less attractive option for ordinary people.

KSEB, however, argues that there is another side to the issue raised earlier by Bharathan. According to the utility, grid-connected solar units can impose additional costs on consumers. In Kerala, peak electricity demand occurs between 6 p.m. and 11 p.m., whereas households that both produce and consume solar energy (prosumers) use only about 36% of the power they generate. The rest is exported to the grid. But at night, they draw back about 45% of their supplied energy. On average, KSEB purchases only 19% of the solar power generated daily.

This mismatch adds financial pressure: because electricity costs rise during peak hours, KSEB estimates that the power banking arrangement could result in losses of nearly Rs 500 crore in FY 2024–25. This translates into a 19-paise increase per unit of electricity for Kerala’s 13 million consumers.

If rooftop solar systems above 3 kW are installed without battery storage, this burden is expected to rise further in coming years. KSEB projects that by 2034–35, consumers may face an additional 39 paise per unit due to this imbalance. These figures form the basis of the argument for making battery storage mandatory, though such a move poses another serious challenge for scaling up rooftop solar projects. At present, Kerala ranks fourth in India in terms of installed rooftop solar capacity, behind Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan.

Regulatory Impacts on Rooftop Solar Adoption

The regulatory framework may further affect adoption. The Kerala State Electricity Regulatory Commission (KSERC) has proposed restricting net metering to systems under 3 kW, down sharply from the earlier 1 MW limit. Larger consumers would instead fall under net billing or gross metering, which are far less favourable.

Financial implications are significant. Under net billing, exported solar power is priced at the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) discovered tariff, often as low as Rs 2–2.5 per kWh, compared to the Rs 3.59 per kWh retail tariff that consumers pay when buying from the grid. This pricing difference reduces savings and extends the payback period of rooftop solar investments. Moreover, households may need to install costly battery storage systems, which are not subsidized and can cost Rs 16,000–18,000 per kWh of capacity.

Market Consequences

Impact on adoption has already become visible. Reports suggest that Kerala’s monthly rooftop solar installation rate has dropped from 15 MW to just 5–6 MW since the draft regulations were introduced. While regulators argue the changes are necessary to ensure grid stability and minimize utility losses, the burden of balancing the grid has effectively been shifted to individual consumers. This risks discouraging both new and existing users from investing in rooftop solar, potentially slowing down Kerala’s progress toward its 2040 renewable energy and 2050 carbon-neutrality goals.

Perinjanam’s New Phase

“As part of the next stage of growth, Perinjanam is set to introduce battery storage as a new model,” says Sachith. A Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) in solar refers to a sophisticated system that stores electrical energy generated from solar panels in advanced rechargeable batteries for later use. This allows energy to be captured during peak solar production, stored when the sun isn’t shining, and then discharged during times of high demand or low solar output. BESS systems improve grid stability by balancing supply and demand, provide backup power during outages, and enhance the integration of intermittent renewable energy sources like solar.

“In our model, the electricity we generate will be stored and then supplied to KSEB during peak hours. At present, we receive just Rs 2.83 per unit, but with this system it could increase to as much as seven rupees,” Sachith explains. He stresses that such storage models must be widely implemented across Kerala. The Perinjanam project is already moving forward with this plan. The first unit will have a 500-kilowatt capacity, with an investment of around Rs 1.5 crore for battery storage. Of this, 10% will be contributed by the consumer committee, while the remaining 90% will come from a mix of 50% subsidy and 40% viability gap funding. The committee has also demanded a 20% profit margin.

With the successful implementation of this initiative, Perinjanam Solar is expected to gain greater recognition and be discussed at a much larger scale…

(This story was produced with support from Internews Earth Journalism Network)

Society

Guterres to WMO: ‘No Country Is Safe Without Early Warnings’

At WMO’s 75th anniversary, UN Chief António Guterres warned that no nation is safe from extreme weather — urging governments to fast-track early warning systems by 2027.

Declaring that “no country is safe from the devastating impacts of extreme weather,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a global surge in early warning systems to protect lives, economies, and ecosystems from climate-fuelled disasters.

Speaking at the 75th anniversary of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Guterres hailed the agency as “a barometer of truth” and “a shining example of science supporting humanity.” It was his first address to the WMO, reflecting the agency’s central role in turning climate science into life-saving action.

“Without your rigorous modelling and forecasting, we would not know what lies ahead — or how to prepare for it,” he told delegates gathered at WMO headquarters in Geneva.

The occasion doubled as the midway checkpoint for the Early Warnings for All (EW4All) initiative, launched by Guterres in 2022 to ensure every person on Earth is protected by life-saving warning systems by 2027.

WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo issued a “Call to Action,” urging all countries to close early warning gaps through expanded observation networks, strengthened hydrological services, and community-level outreach. “Every dollar invested in early warning saves up to fifteen in disaster losses,” she said.

Saulo cautioned that despite major progress—108 countries now operate multi-hazard warning systems—the world’s poorest remain the least protected. Disaster mortality rates are six times higher in countries with limited early warning coverage.

A 75-Year Legacy of Science for Action

Marking 75 years since it became a UN specialized agency, WMO used its Extraordinary Congress to reaffirm global cooperation in weather, water, and climate monitoring.

President Abdulla al Mandous praised Guterres for embedding early warning systems into the international climate agenda: “Early warnings are now recognized at the highest levels as cost-effective, life-saving, and cross-cutting solutions that reduce risk and advance development,” he said.

Guterres urged three urgent priorities to achieve universal coverage: integrating early warnings across governance structures, boosting finance and debt relief for vulnerable nations, and aligning national climate plans to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C.

“Every life lost to disaster is one too many,” he said. “With science, solidarity, and political resolve, we can ensure a safer planet for all.”

Society

Understanding AI: The Science, Systems, and Industries Powering a $3.6 Trillion Future

Explore how artificial intelligence is transforming finance, automation, and industry — and what the $3.6 trillion AI boom means for our future

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a major point of discussion and a defining technological frontier of our time. Experiencing remarkable growth in recent years, AI refers to computer systems capable of mimicking intelligent human cognitive abilities such as learning, problem-solving, critical decision-making, and creativity. Its ability to identify objects, understand human language, and act autonomously makes it increasingly feasible for industries like automotive manufacturing, financial services, and fraud detection.

As of 2024, the global AI market is valued at approximately USD 638.23 billion, marking an 18.6% increase from 2023, and is projected to reach USD 3,680.47 billion by 2034 (Precedence Research). North America leads this global growth with a 36.9% market share, dominated by the United States and Canada. The U.S. AI market alone is valued at around USD 146.09 billion in 2024, representing nearly 22% of global AI investments.

The Early Evolution of AI: From Reactive Machines to Learning Systems

Our understanding of AI has evolved through different models, each representing a step closer to mimicking human intelligence.

Reactive Machines: The First Generation

One of the earliest and most famous AI systems was IBM’s Deep Blue, the chess-playing computer that defeated world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997. Deep Blue was a reactive machine model, relying on brute-force algorithms that evaluated millions of possible moves per second. It could process current data and generate responses, but lacked memory or the ability to learn from past experiences.

Reactive machines are task-specific and cannot adapt to new or unexpected conditions. Despite these limitations, they remain integral to automation, where precision and repeatability are more important than learning—such as in manufacturing or assembly-line robotics.

Limited Memory AI: Learning from Experience

To overcome the rigidity of reactive machines, researchers developed Limited Memory AI, a model that can store and recall past data to make more informed decisions. This model powers technologies such as self-driving cars, which constantly analyze road conditions, objects, and obstacles, using stored data to adjust their behaviour.

Limited Memory AI is also valuable in financial forecasting, where it uses historical market data to predict trends. However, its memory capacity is still finite, making it less suited for complex reasoning or tasks like Natural Language Processing (NLP) that require deeper contextual understanding.

Theoretical Models: Towards Human-Like Intelligence

Theory of Mind AI

The next conceptual step is Theory of Mind AI, a model designed to understand human emotions, beliefs, and intentions. This approach aims to enable AI systems to interact socially with humans, interpreting emotional cues and behavioral patterns.

Researchers like Neil Rabinowitz from Google DeepMind have developed early prototypes such as ToMnet, which attempts to simulate aspects of human reasoning. ToMnet uses artificial neural networks modeled after brain function to predict and interpret behavior. However, replicating the complexity of human mental states remains a distant goal, and these systems are still largely experimental.

Self-Aware AI: The Future Frontier

The ultimate ambition of AI research is self-aware AI — systems that possess conscious awareness and a sense of identity. While this remains speculative, the potential applications are vast. Self-aware AI could revolutionize fields like environmental management, creating bots capable of predicting ecosystem changes and implementing conservation strategies autonomously.

In education, self-aware systems could understand a student’s cognitive style and deliver personalized learning experiences, adapting dynamically to each learner.

However, replicating human self-awareness is extraordinarily complex. The human brain’s intricate memory, emotion, and decision-making systems remain only partially understood. Additionally, self-aware AI raises profound ethical and privacy concerns, as such systems would require massive amounts of sensitive data. Strict guidelines for data collection, storage, and usage would be essential before such systems could be deployed responsibly.

Artificial Intelligence in the Financial Services Industry

The financial sector has undergone a massive transformation powered by AI-driven analytics, automation, and predictive intelligence. AI enhances Corporate Performance Management (CPM) by improving speed and precision in financial planning, investment analysis, and risk management.

Natural Language Processing and Automation

Leading financial firms such as JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs employ Natural Language Processing (NLP) — AI systems that understand human language — to streamline customer interaction and analyze market information. NLP tools like chatbots handle millions of customer queries efficiently, while advanced systems process unstructured text data from financial reports and news sources to inform investment decisions.

Paired with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and document parsing, NLP systems can convert scanned or image-based documents into machine-readable text, accelerating compliance checks, fraud detection, and financial forecasting.

However, the accuracy of NLP models depends on the quality and diversity of training data. Biased or incomplete data can lead to errors in analysis, potentially influencing high-stakes financial decisions.

Generative AI in Finance

Another major shift in finance comes from Generative AI, a branch of AI that creates new content — including text, images, videos, and even financial models — based on learned patterns. Using Large Language Models (LLMs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), these systems simulate complex financial scenarios, improving fraud detection and stress testing.

For instance, PayPal and American Express use generative AI to simulate fraudulent transaction patterns, strengthening their security systems. Transformers — deep learning architectures behind tools like OpenAI’s GPT — enable these models to understand and generate human-like language, allowing them to summarize extensive reports, produce research briefs, and assist analysts in decision-making.

Yet, Generative AI also presents challenges. It can be manipulated through adversarial attacks, producing misleading or biased outputs if trained on flawed data. Ensuring transparency and fairness in training datasets remains critical to prevent discriminatory outcomes, especially in credit scoring and loan assessment.

AI and Automation: Revolutionizing Industry Operations

Artificial Intelligence has become a cornerstone of intelligent automation (IA), reshaping business process management (BPM) and robotic process automation (RPA). Traditional RPA handled repetitive, rule-based tasks, but with AI integration, these systems can now manage complex workflows that require contextual decision-making.

AI-driven automation enhances productivity, reduces operational costs, and increases accuracy. For example, in manufacturing, AI-enabled systems perform predictive maintenance by analyzing sensor data to detect machinery issues before failures occur, minimizing downtime and extending equipment lifespan.

In the automotive sector, AI-powered machine vision systems inspect car components with higher accuracy than human inspectors, ensuring consistent quality and safety. These innovations make automation not only efficient but also economically advantageous for large-scale industries.

Machine Learning: The Engine of Artificial Intelligence

At the heart of AI lies Machine Learning (ML) — algorithms that allow computers to learn from data and improve over time without explicit programming. Three fundamental ML models underpin most modern AI applications: Decision Trees, Linear Regression, and Logistic Regression.

Decision Trees

Decision trees simplify complex decision-making processes into intuitive, branching structures. Each branch represents a decision rule, and each leaf node gives an outcome or prediction. This makes them powerful tools for disease diagnosis in healthcare and credit risk assessment in finance. They handle both numerical and categorical data, offering transparency and interpretability.

Linear Regression

Linear regression models relationships between one dependent and one or more independent variables, making it useful for predictive analytics such as stock price forecasting. It applies mathematical techniques like Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) or Gradient Descent to optimize prediction accuracy. Its simplicity, efficiency, and scalability make it ideal for large datasets.

Logistic Regression

While linear regression predicts continuous outcomes, logistic regression is used for classification problems — determining whether an instance belongs to a particular category (e.g., yes/no, fraud/genuine). It calculates probabilities between 0 and 1 using a sigmoid function, providing fast and interpretable results. Logistic regression is widely used in healthcare (disease prediction) and finance (loan default assessment).

Types of Machine Learning Algorithms

Machine Learning can be broadly classified into Supervised, Unsupervised, and Reinforcement Learning — each suited for different problem types.

Supervised Learning

In supervised learning, algorithms train on labelled datasets to identify patterns and make predictions. Once trained, they can generalize to new, unseen data. Applications include spam filtering, voice recognition, and image classification.

Supervised models handle both classification (categorical predictions) and regression (continuous predictions). Their strength lies in high accuracy and reliability when trained on quality data.

Unsupervised Learning

Unsupervised learning, in contrast, deals with unlabelled data. It identifies hidden patterns or groupings within datasets, commonly used in customer segmentation, market basket analysis, and anomaly detection.

By autonomously discovering relationships, unsupervised learning reduces human bias and is valuable in exploratory data analysis.

Reinforcement Learning (Optional Expansion)

While not yet as mainstream, reinforcement learning trains algorithms through trial and error, rewarding desired outcomes. It is foundational in robotics, autonomous systems, and game AI — including the systems that now outperform humans in complex strategic games like Go or StarCraft.

Ethical and Societal Considerations of AI

Despite its transformative potential, AI raises significant ethical and privacy challenges. Issues such as algorithmic bias, data exploitation, and job displacement are increasingly at the forefront of public discourse.

Ethical AI demands transparent data practices, accountability in algorithm design, and equitable access to technology. Governments and academic institutions, including Capitol Technology University (captechu.edu), emphasize developing AI systems that align with social good, human rights, and sustainability.

Furthermore, the rise of generative AI has intensified debates about content authenticity, intellectual property, and deepfake misuse, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive AI regulation.

A Technology Still in Transition

Artificial Intelligence stands at the intersection of opportunity and uncertainty. From Deep Blue’s deterministic algorithms to generative AI’s creative engines, the technology has redefined industries and continues to evolve at an unprecedented pace.

While self-aware AI and full cognitive autonomy remain theoretical, the rapid integration of AI across industries signals an irreversible shift toward machine-augmented intelligence. The challenge ahead is ensuring that this evolution remains ethical, inclusive, and sustainable — using AI to enhance human potential, not replace it.

References

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Market Size to Reach USD 3,680.47 Bn by 2034 – Precedence Research

- What is AI, how does it work and what can it be used for? – BBC

- 10 Ways Companies Are Using AI in the Financial Services Industry – OneStream

- The Transformative Power of AI: Impact on 18 Vital Industries – LinkedIn

- What Is Artificial Intelligence (AI)? – IBM

- The Ethical Considerations of Artificial Intelligence – Capitol Technology University

- What is Generative AI? – Examples, Definition & Models – GeeksforGeeks

Society

The Dragon and the Elephant Dance for a Cleaner World

New reports from the IEA and Ember show that China and India are leading a global turning point — where renewables now outpace fossil fuels.

In late September, EdPublica reported an inspirational story from Perinjanam, a quiet coastal village in the South Indian state Kerala, where rooftops gleam with solar panels and homes have turned into micro power plants. It was a story of how ordinary citizens, through community effort and government support, took part in a just energy transition.

That local story, seemingly small, was in fact a mirror of a far bigger movement unfolding worldwide. Now, two major global reports–one from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and another from the independent think tank Ember–confirm that the world is entering a decisive new phase in its energy transformation. Together, their findings show that 2025 is shaping up to be the turning point year: the moment when renewables not only surpassed coal but began meeting all new global electricity demand. The year will likely be remembered as the moment when the global energy transition stopped being a promise and became a measurable reality — led by the two Asian giants, China and India.

The Global Picture: IEA’s Big Forecast

‘The IEA’s Renewables 2025’ report, released on October 7, paints an extraordinary picture of growth and possibility. Despite global headwinds — including high interest rates, supply chain bottlenecks, and policy shifts — renewable energy capacity is projected to more than double by 2030, adding 4,600 gigawatts (GW) of new renewable power.

To grasp that number: it’s equivalent to building the entire current electricity generation capacity of China, the European Union, and Japan combined.

At the centre of this boom is solar photovoltaic (PV) technology, which will account for around 80% of the total growth. The IEA calls solar “the backbone of the energy transition,” driven by falling costs, faster permitting processes, and widespread adoption across emerging economies. Wind, hydropower, bioenergy, and geothermal follow closely behind, expanding capacity even as global systems adapt to higher shares of variable power.

“The growth in global renewable capacity in the coming years will be dominated by solar PV – but with wind, hydropower, bioenergy and geothermal all contributing, too,” said Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the IEA. “As renewables’ role in electricity systems rises in many countries, policymakers need to play close attention to supply chain security and grid integration challenges.”

The IEA forecasts particularly rapid progress in emerging markets. India is set to become the second-largest renewables growth market in the world, after China, reaching its ambitious 2030 targets comfortably. The report highlights new policy instruments — such as auction programs and rooftop solar incentives — that are spurring confidence across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

In India, the expansion of corporate power purchase agreements, utility contracts, and merchant renewable plants is also driving a quiet revolution, accounting for nearly 30% of global renewable capacity expansion to 2030.

At the same time, challenges remain. The IEA points to a worrying concentration of solar PV manufacturing in China, where over 90% of supply chain capacity for key components like polysilicon and rare earth materials is expected to remain by 2030.

Grid integration is another bottleneck. As solar and wind grow, many countries are already facing curtailments — when renewable power cannot be fed into the grid due to overload or mismatch in demand. The IEA stresses the need for urgent investment in transmission infrastructure, storage technologies, and flexible generation to prevent this momentum from being wasted.

Evidence on the Ground

If the IEA’s report is a map of where we’re going, Ember’s Mid-Year Global Electricity Review 2025 shows where we are right now — and the signs are unmistakable.

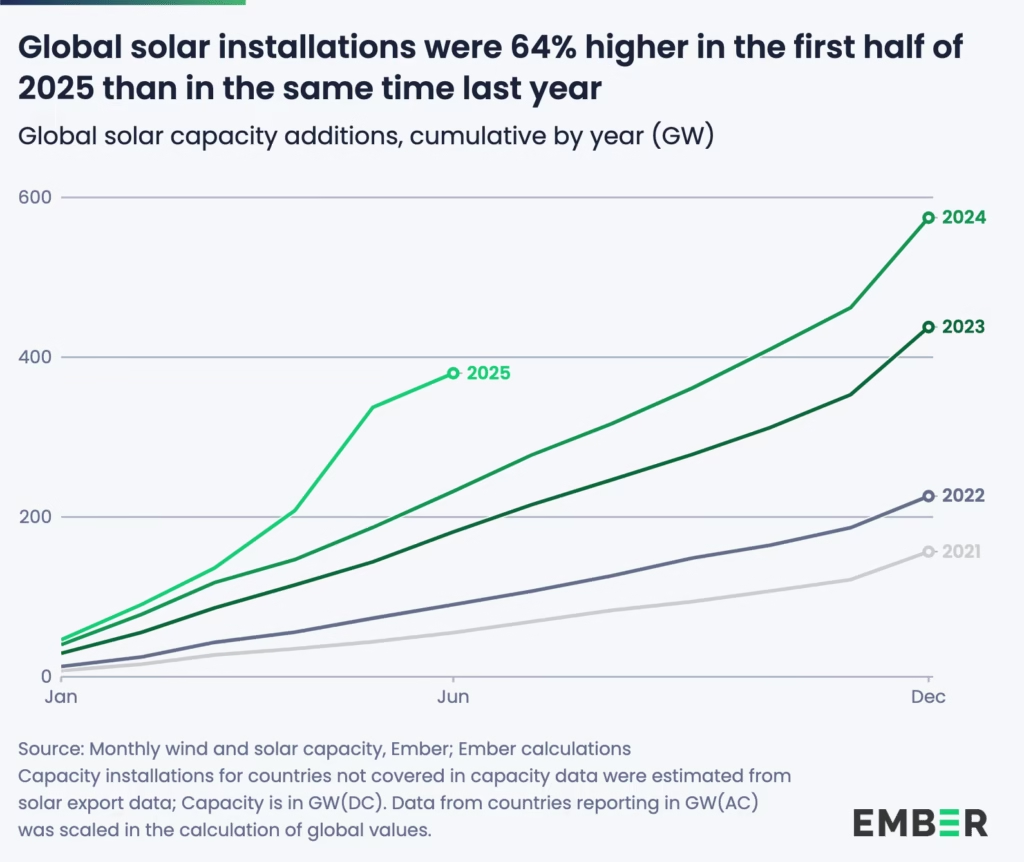

Ember’s data, covering the first half of 2025, reveals that solar and wind met all of the world’s rising electricity demand — and even caused a slight decline in fossil fuel generation. It’s a first in recorded history.

“We are seeing the first signs of a crucial turning point,” said Małgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, Senior Electricity Analyst at Ember. “Solar and wind are now growing fast enough to meet the world’s growing appetite for electricity. This marks the beginning of a shift where clean power is keeping pace with demand growth.”

Global electricity demand rose by 2.6% in early 2025, adding about 369 terawatt-hours (TWh) compared with the same period last year. Solar alone met 83% of that rise, thanks to record generation growth of 306 TWh, a year-on-year increase of 31%. Wind contributed another 97 TWh, leading to a net decline in both coal and gas generation.

Coal generation fell 0.6% (-31 TWh) and gas 0.2% (-6 TWh), marking a combined fossil decline of 0.3% (-27 TWh). As a result, global power sector emissions fell by 0.2%, even as demand continued to grow.

Most significantly, for the first time ever, renewables generated more power than coal. Renewables supplied 5,072 TWh, overtaking coal’s 4,896 TWh — a symbolic but historic milestone.

“Solar and wind are no longer marginal technologies — they are driving the global power system forward,” said Sonia Dunlop, CEO of the Global Solar Council. “The fact that renewables have overtaken coal for the first time marks a historic shift.”

China and India Lead the Way

The two reports together highlight that the epicenter of the clean energy shift is now in Asia.

According to Ember, China’s fossil generation fell by 2% (-58.7 TWh) in the first half of 2025, as clean power growth outpaced rising electricity demand. Solar generation jumped 43% (+168 TWh), and wind grew 16% (+79 TWh), together helping cut the country’s power sector emissions by 1.7% (-47 MtCO₂).

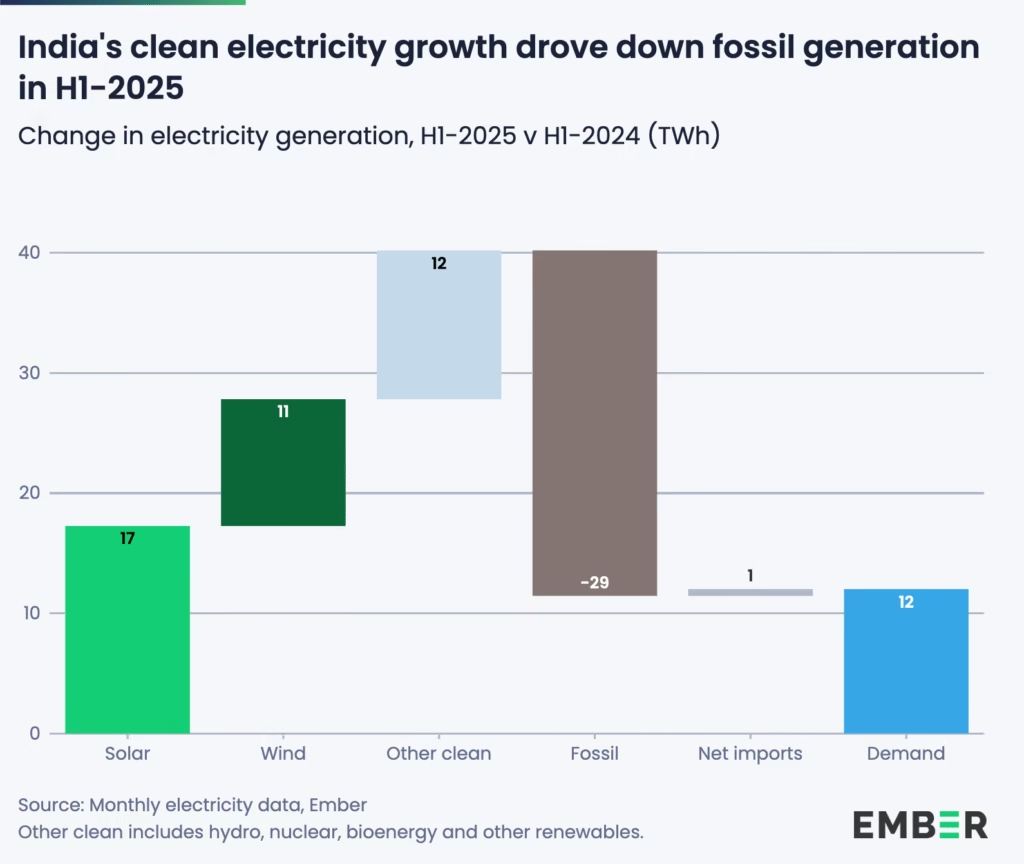

Meanwhile, India’s fossil fuel decline was even steeper in relative terms. Solar and wind generation grew at record pace — solar by 25% (+17 TWh) and wind by 29% (+11 TWh) — while electricity demand rose only 1.3%, far slower than in 2024. The result: coal use dropped 3.1% (-22 TWh) and gas by 34% (-7 TWh), leading to an estimated 3.6% fall in power sector emissions.

For both countries, these numbers align closely with the IEA’s projections. Together, China and India are now the primary engines of renewable capacity growth, demonstrating how large emerging economies can pivot toward clean energy while maintaining development momentum.

Setbacks Elsewhere

Yet progress is uneven. In the United States and European Union, fossil generation actually rose in early 2025.

In the U.S., a 3.6% rise in demand outpaced clean power additions, leading to a 17% increase in coal generation (+51 TWh), though gas use fell slightly. The EU also saw higher gas and coal use due to weaker wind and hydro output.

The IEA attributes part of this slowdown to policy uncertainty, especially in the U.S., where an early phase-out of federal tax incentives has reduced renewable growth expectations by almost 50% compared to last year’s forecast. Europe’s problem is different — a mature but strained grid facing seasonal fluctuations and low wind output.

These regional discrepancies underscore the IEA’s core message: achieving a clean power future isn’t just about building more solar farms, but about building smarter systems — integrated, flexible, and resilient.

Beyond Power

Both reports agree that while renewables are transforming electricity, their impact on transport and heating remains limited.

In transport, the IEA projects renewables’ share to rise modestly from 4% today to 6% in 2030, mostly through electric vehicles and biofuels. In heating, renewables are set to grow from 14% to 18% of global energy use over the same period.

These slower-moving sectors will define the next frontier of decarbonization — one where electrification, hydrogen, and new thermal storage technologies must play a greater role.

The Big Picture

Put together, the IEA’s forecasts and Ember’s real-world data signal that the clean energy transition has passed the point of no return.

Solar and wind are no longer simply catching up — they are now shaping global power dynamics. Their continued expansion is not only meeting new demand but beginning to displace fossil fuels outright.

“As costs of technologies continue to fall, now is the perfect moment to embrace the economic, social and health benefits that come with increased solar, wind and batteries,” said Ember’s Wiatros-Motyka.

Yet both agencies caution: to sustain this momentum, governments must expand grid capacity, diversify supply chains, and improve energy storage systems. Without these, the 2025 breakthrough could become a bottleneck.

A Symbol and a Signal

In a way, the world in 2025 looks a lot like Perinjanam did a few years ago — a place where optimism met obstacles, but the light won. What was once a village-scale transition is now a planetary transformation, proving that even small local models can foreshadow global change.

From Kerala’s rooftops to China’s vast solar parks, from India’s wind corridors to Africa’s mini-grids, the direction is unmistakable: the sun and wind are powering the next phase of human progress.

If 2024 was the year of warnings, 2025 is the year of evidence. The global energy system is finally tilting toward sustainability — not someday, but today.

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Know The Scientist6 months ago

Know The Scientist6 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoRemembering S.N. Bose, the underrated maestro in quantum physics

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoWhy the Arts Matter As Much As Science or Math

-

Earth5 months ago

Earth5 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

Pingback: Big Fashion’s Fossil-Fuel Addiction: The Clean Heat Opportunity Being Ignored - EdPublica

Pingback: The Dragon and the Elephant Dance for a Cleaner World - EdPublica

Pingback: Gujarat, Kerala Top India’s Rooftop Solar Race as PMSGY Expands, Yet Financial Bottlenecks Linger - EdPublica