Space & Physics

A New Milestone in Quantum Error Correction

This achievement moves quantum computing closer to becoming a transformative tool for science and technology

Quantum computing promises to revolutionize fields like cryptography, drug discovery, and optimization, but it faces a major hurdle: qubits, the fundamental units of quantum computers, are incredibly fragile. They are highly sensitive to external disturbances, making today’s quantum computers too error-prone for practical use. To overcome this, researchers have turned to quantum error correction, a technique that aims to convert many imperfect physical qubits into a smaller number of more reliable logical qubits.

In the 1990s, researchers developed the theoretical foundations for quantum error correction, showing that multiple physical qubits could be combined to create a single, more stable logical qubit. These logical qubits would then perform calculations, essentially turning a system of faulty components into a functional quantum computer. Michael Newman, a researcher at Google Quantum AI, highlights that this approach is the only viable path toward building large-scale quantum computers.

However, the process of quantum error correction has its limits. If physical qubits have a high error rate, adding more qubits can make the situation worse rather than better. But if the error rate of physical qubits falls below a certain threshold, the balance shifts. Adding more qubits can significantly improve the error rate of the logical qubits.

A Breakthrough in Error Correction

In a paper published in Nature last December, Michael Newman and his team at Google Quantum AI have achieved a major breakthrough in quantum error correction. They demonstrated that by adding physical qubits to a system, the error rate of a logical qubit drops sharply. This finding shows that they’ve crossed the critical threshold where error correction becomes effective. The research marks a significant step forward, moving quantum computers closer to practical, large-scale applications.

The concept of error correction itself isn’t new — it is already used in classical computers. On traditional systems, information is stored as bits, which can be prone to errors. To prevent this, error-correcting codes replicate each bit, ensuring that errors can be corrected by a majority vote. However, in quantum systems, things are more complicated. Unlike classical bits, qubits can suffer from various types of errors, including decoherence and noise, and quantum computing operations themselves can introduce additional errors.

Moreover, unlike classical bits, measuring a qubit’s state directly disturbs it, making it much harder to identify and correct errors without compromising the computation. This makes quantum error correction particularly challenging.

The Quantum Threshold

Quantum error correction relies on the principle of redundancy. To protect quantum information, multiple physical qubits are used to form a logical qubit. However, this redundancy is only beneficial if the error rate is low enough. If the error rate of physical qubits is too high, adding more qubits can make the error correction process counterproductive.

Google’s recent achievement demonstrates that once the error rate of physical qubits drops below a specific threshold, adding more qubits improves the system’s resilience. This breakthrough brings researchers closer to achieving large-scale quantum computing systems capable of solving complex problems that classical computers cannot.

Moving Forward

While significant progress has been made, quantum computing still faces many engineering challenges. Quantum systems require extremely controlled environments, such as ultra-low temperatures, and the smallest disturbances can lead to errors. Despite these hurdles, Google’s breakthrough in quantum error correction is a major step toward realizing the full potential of quantum computing.

By improving error correction and ensuring that more reliable logical qubits are created, researchers are steadily paving the way for practical quantum computers. This achievement moves quantum computing closer to becoming a transformative tool for science and technology.

Space & Physics

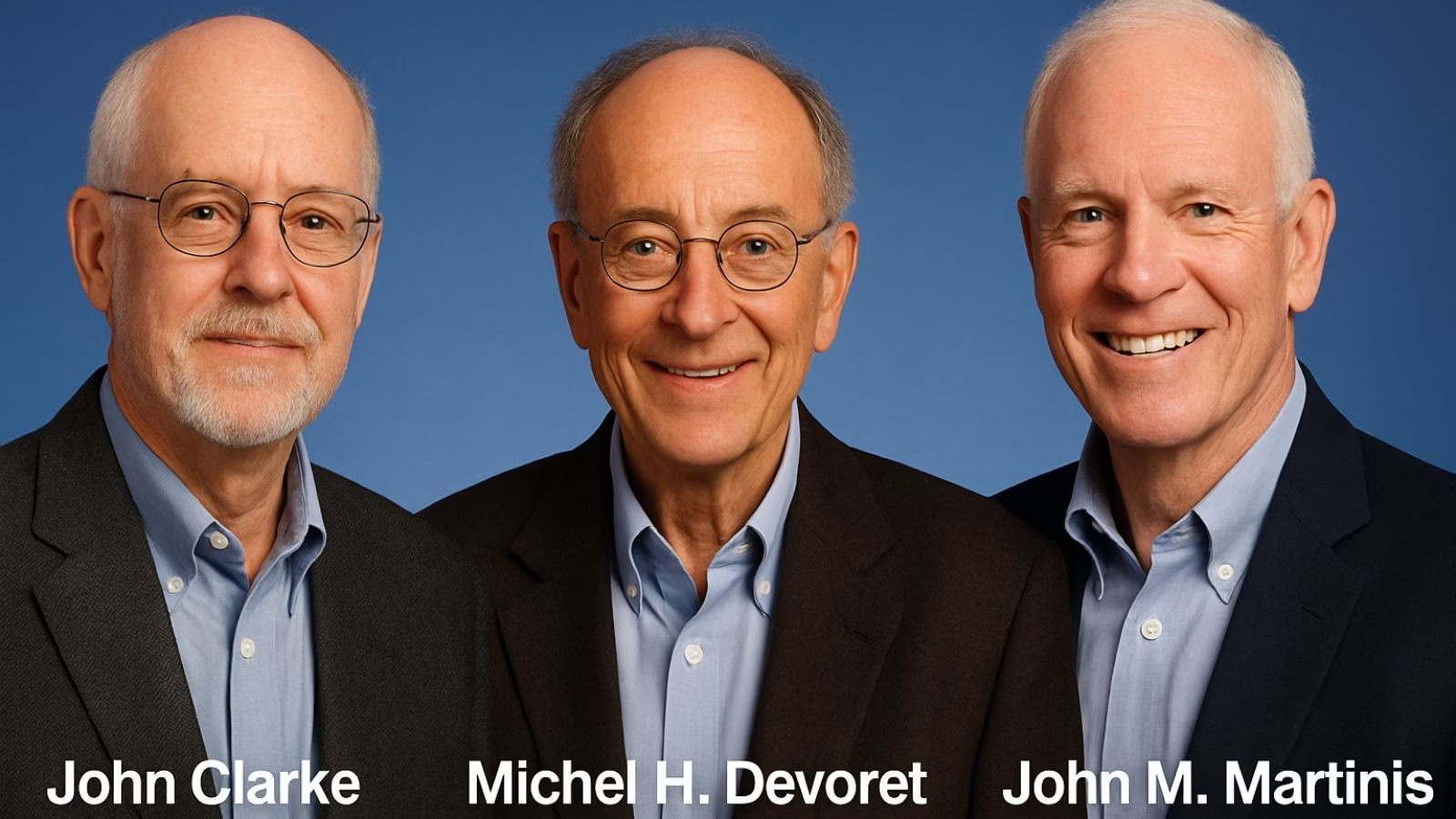

Nobel Prize in Physics: Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis Honoured for Pioneering Quantum Discoveries

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics honours John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for revealing how entire electrical circuits can display quantum behaviour — a discovery that paved the way for modern quantum computing.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for their landmark discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit, an innovation that laid the foundation for today’s quantum computing revolution.

Announcing the prize, Olle Eriksson, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said, “It is wonderful to be able to celebrate the way that century-old quantum mechanics continually offers new surprises. It is also enormously useful, as quantum mechanics is the foundation of all digital technology.”

The Committee described their discovery as a “turning point in understanding how quantum mechanics manifests at the macroscopic scale,” bridging the gap between classical electronics and quantum physics.

John Clarke: The SQUID Pioneer

British-born John Clarke, Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, is celebrated for his pioneering work on Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) — ultra-sensitive detectors of magnetic flux. His career has been marked by contributions that span superconductivity, quantum amplifiers, and precision measurements.

Clarke’s experiments in the early 1980s provided the first clear evidence of quantum behaviour in electrical circuits — showing that entire electrical systems, not just atoms or photons, can obey the strange laws of quantum mechanics.

A Fellow of the Royal Society, Clarke has been honoured with numerous awards including the Comstock Prize (1999) and the Hughes Medal (2004).

Michel H. Devoret: Architect of Quantum Circuits

French physicist Michel H. Devoret, now the Frederick W. Beinecke Professor Emeritus of Applied Physics at Yale University, has been one of the intellectual architects of quantronics — the study of quantum phenomena in electrical circuits.

After earning his PhD at the University of Paris-Sud and completing a postdoctoral fellowship under Clarke at Berkeley, Devoret helped establish the field of circuit quantum electrodynamics (cQED), which underpins the design of modern superconducting qubits.

His group’s innovations — from the single-electron pump to the fluxonium qubit — have set performance benchmarks in quantum coherence and control. Devoret is also a recipient of the Fritz London Memorial Prize (2014) and the John Stewart Bell Prize, and is a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

John M. Martinis: Building the Quantum Processor

American physicist John M. Martinis, who completed his PhD at UC Berkeley under Clarke’s supervision, translated these quantum principles into the hardware era. His experiments demonstrated energy level quantisation in Josephson junctions, one of the key results now honoured by the Nobel Committee.

Martinis later led Google’s Quantum AI lab, where his team in 2019 achieved the world’s first demonstration of quantum supremacy — showing a superconducting processor outperforming the fastest classical supercomputer on a specific task.

A former professor at UC Santa Barbara, Martinis continues to be a leading voice in quantum computing research and technology development.

A Legacy of Quantum Insight

Together, the trio’s discovery, once seen as a niche curiosity in superconducting circuits, has become the cornerstone of the global quantum revolution. Their experiments proved that macroscopic electrical systems can display quantised energy states and tunnel between them, much like subatomic particles.

Their work, as the Nobel citation puts it, “opened a new window into the quantum behaviour of engineered systems, enabling technologies that are redefining computation, communication, and sensing.”

Space & Physics

The Tiny Grip That Could Reshape Medicine: India’s Dual-Trap Optical Tweezer

Indian scientists build new optical tweezer module—set to transform single-molecule research and medical Innovation

In an inventive leap that could open up new frontiers in neuroscience, drug development, and medical research, scientists in India have designed their own version of a precision laboratory tool known as the dual-trap optical tweezers system. By creating a homegrown solution to manipulate and measure forces on single molecules, the team brings world-class technology within reach of Indian researchers—potentially igniting a wave of scientific discoveries.

Optical tweezers, a Nobel Prize-winning invention from 2018, use focused beams of light to grab and move microscopic objects with extraordinary accuracy. The technique has become indispensable for measuring tiny forces and exploring the mechanics of DNA, proteins, living cells, and engineered nanomaterials. Yet, decades after their invention, conventional optical tweezers systems sometimes fall short for today’s most challenging experiments.

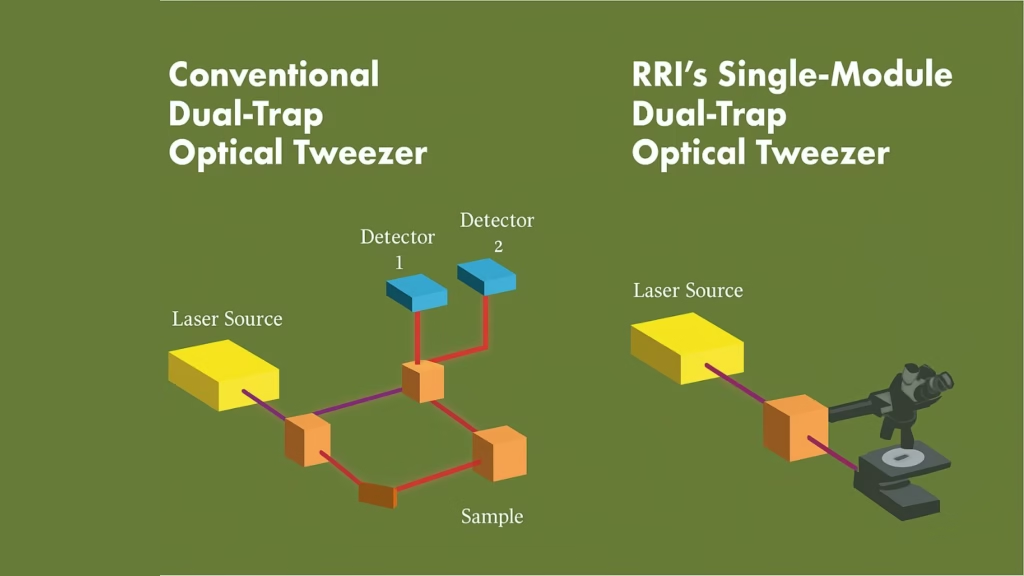

Researchers at the Raman Research Institute (RRI), an autonomous institute backed by India’s Department of Science and Technology in Bengaluru, have now introduced a smart upgrade that addresses long-standing pitfalls of dual-trap tweezers. Traditional setups rely on measuring the light that passes through particles trapped in two separate beams—a method prone to signal “cross-talk.” This makes simultaneous, independent measurement difficult, diminishing both accuracy and versatility.

The new system pioneers a confocal detection scheme. In a media statement, Md Arsalan Ashraf, a doctoral scholar at RRI, explained, “The unique optical trapping scheme utilizes laser light scattered back by the sample for detecting trapped particle position. This technique pushes past some of the long-standing constraints of dual-trap configurations and removes signal interference. The single-module design integrates effortlessly with standard microscopy frameworks,” he said.

The refinement doesn’t end there. The system ensures that detectors tracking tiny particles remain perfectly aligned, even when the optical traps themselves move. The result: two stable, reliable measurement channels, zero interference, and no need for complicated re-adjustment mid-experiment—a frequent headache with older systems.

Traditional dual-trap designs have required costly and complex add-ons, sometimes even hijacking the features of laboratory microscopes and making additional techniques, such as phase contrast or fluorescence imaging, hard to use. “This new single-module trapping and detection design makes high-precision force measurement studies of single molecules, probing of soft materials including biological samples, and micromanipulation of biological samples like cells much more convenient and cost-effective,” said Pramod A Pullarkat, lead principal investigator at RRI, in a statement.

By removing cross-talk and offering robust stability—whether traps are close together, displaced, or the environment changes—the RRI team’s approach is not only easier to use but far more adaptable. Its plug-and-play module fits onto standard microscopes without overhauling their basic structure.

From the intellectual property point of view, this design may be a game-changer. By cracking the persistent problem of signal interference with minimalist engineering, the new setup enhances measurement precision and reliability—essential advantages for researchers performing delicate biophysical experiments on everything from molecular motors to living cells.

With the essential building blocks in place, the RRI team is now exploring commercial avenues to produce and distribute their single-module, dual-trap optical tweezer system as an affordable add-on for existing microscopes. The innovation stands to put advanced single-molecule force spectroscopy, long limited to wealthier labs abroad, into the hands of scientists across India—and perhaps spark breakthroughs across the biomedical sciences.

Space & Physics

New Magnetic Transistor Breakthrough May Revolutionize Electronics

A team of MIT physicists has created a magnetic transistor that could make future electronics smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient. By swapping silicon for a new magnetic semiconductor, they’ve opened the door to game-changing advancements in computing.

For decades, silicon has been the undisputed workhorse in transistors—the microscopic switches responsible for processing information in every phone, computer, and high-tech device. But silicon’s physical limits have long frustrated scientists seeking ever-smaller, more efficient electronics.

Now, MIT researchers have unveiled a major advance: they’ve replaced silicon with a magnetic semiconductor, introducing magnetism into transistors in a way that promises tighter, smarter, and more energy-saving circuits. This new ingredient, chromium sulfur bromide, makes it possible to control electricity flow with far greater efficiency and could even allow each transistor to “remember” information, simplifying circuit design for future chips.

“This lack of contamination enables their device to outperform existing magnetic transistors. Most others can only create a weak magnetic effect, changing the flow of current by a few percent or less. Their new transistor can switch or amplify the electric current by a factor of 10,” the MIT team said in a media statement. Their work, detailed in Physical Review Letters, outlines how this material’s stability and clean switching between magnetic states unlocks a new degree of control.

Chung-Tao Chou, MIT graduate student and co-lead author, explains in a media statement, “People have known about magnets for thousands of years, but there are very limited ways to incorporate magnetism into electronics. We have shown a new way to efficiently utilize magnetism that opens up a lot of possibilities for future applications and research.”

The device’s game-changing aspect is its ability to combine the roles of memory cell and transistor, allowing electronics to read and store information faster and more reliably. “Now, not only are transistors turning on and off, they are also remembering information. And because we can switch the transistor with greater magnitude, the signal is much stronger so we can read out the information faster, and in a much more reliable way,” said Luqiao Liu, MIT associate professor, in a media statement.

Moving forward, the team is looking to scale up their clean manufacturing process, hoping to create arrays of these magnetic transistors for broader commercial and scientific use. If successful, the innovation could usher in a new era of spintronic devices, where magnetism becomes as central to electronics as silicon is today.

-

Space & Physics5 months ago

Space & Physics5 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Earth6 months ago

Earth6 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoDid JWST detect “signs of life” in an alien planet?

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

-

Society6 months ago

Society6 months agoRabies, Bites, and Policy Gaps: One Woman’s Humane Fight for Kerala’s Stray Dogs