Society

Reborn; India’s 1600-year-old Ivy League University

Thousands of years ago, Nalanda was burnt to ashes. Today, from those ashes, a new Nalanda is rising. The new campus of Nalanda has been built at a cost of Rs 1,800 crore.

Once a beacon of knowledge, Nalanda University stood as one of the most prestigious educational institutions in ancient India. Its halls echoed with the footsteps of scholars from across the world, who came to immerse themselves in diverse fields of study. However, this illustrious centre of learning faced destruction due to foreign invasions, leading to centuries of dormancy.

In a significant turn of events, the echoes of Nalanda’s scholarly past are being rekindled. On June 19, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the new campus of Nalanda University, symbolizing a revival of its 1600-year-old legacy. This modern resurrection aims to restore and celebrate the ancient university’s historical importance while positioning it as a global hub for education once again.

Between the 5th and 13th centuries, Nalanda University flourished as a world-renowned institution, earning immense admiration within India’s education system and beyond. Its international reputation attracted students from China, Mongolia, Tibet, Korea, and other Asian countries, all eager to study on its esteemed campus. Known for its high standard of teaching, Nalanda was especially prominent as a centre for Mahayana Buddhist philosophy.

While inaugurating the new campus, the Prime Minister said that Nalanda embodies India’s identity, respect, value and mantra

Ayurveda, Buddhism, Mathematics, Grammar, Astronomy, Indian Philosophy and many other subjects were taught at Nalanda, the world’s first residential university. The famous Indian mathematician Aryabhata was a teacher here in the 6th century. The university’s library, known as Dharma Gunj or the Mountain of Truth, was legendary. It housed an astounding collection of 9 million palm leaf manuscripts, making it one of the most famous libraries of its time.

At the end of the 12th century, Turko-Afghan military general Bakhtiyar Khilji destroyed this great university and burnt its priceless library. Considering the fact that ancient Nalanda was a symbol of Asian unity and strength, now Nalanda International University is being established near the land where the remnants of old Nalanda lie. While inaugurating the new campus, the Prime Minister said that Nalanda embodies India’s identity, respect, value and mantra. Modi inaugurated Nalanda within 10 days of taking oath as Prime Minister for the third time. Central government is giving so much importance to this project.

The idea of reviving Nalanda University took off in 2007 at the Second East Asia Summit when sixteen member countries agreed. In 2009, at the Fourth East Asia Summit, ASEAN member states including Australia, China, Korea, Singapore and Japan pledged their support

Nalanda University is located in Rajgir in Nalanda district of Bihar state. This is a project of special interest to the Ministry of External Affairs. The new campus has been developed with an investment of Rs.1800 crore. It consists of two academic blocks with 40 classrooms with a seating capacity of 1900 students, two auditoriums with a seating capacity of 300 each, a student hostel, an international centre, an amphitheatre with a seating capacity of 2000, a faculty club and a sports complex.

The idea of reviving Nalanda University took off in 2007 at the Second East Asia Summit when sixteen member countries agreed. In 2009, at the Fourth East Asia Summit, ASEAN member states including Australia, China, Korea, Singapore and Japan pledged their support.

The Bihar state government handed over the land acquired from the local people to the university for the new campus. A meeting between Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and the then External Affairs Minister SM Krishna resulted in the central government assuring adequate funds for the project. The university also aims to serve as a bridge for students from different parts of Southeast Asia.

In 2007, the Bihar Legislative Assembly passed a bill to create a new university. The Nalanda University Bill was passed in the Rajya Sabha (the upper house of India’s Parliament) on 21 August 2010 and in the Lok Sabha (the lower house of India’s Parliament) on 26 August 2010. The Bill received the President’s assent on 21 September 2010, thereby becoming a law. The university formally came into existence on 25 November 2010 when the Act was enacted.

Society

Guterres to WMO: ‘No Country Is Safe Without Early Warnings’

At WMO’s 75th anniversary, UN Chief António Guterres warned that no nation is safe from extreme weather — urging governments to fast-track early warning systems by 2027.

Declaring that “no country is safe from the devastating impacts of extreme weather,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a global surge in early warning systems to protect lives, economies, and ecosystems from climate-fuelled disasters.

Speaking at the 75th anniversary of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Guterres hailed the agency as “a barometer of truth” and “a shining example of science supporting humanity.” It was his first address to the WMO, reflecting the agency’s central role in turning climate science into life-saving action.

“Without your rigorous modelling and forecasting, we would not know what lies ahead — or how to prepare for it,” he told delegates gathered at WMO headquarters in Geneva.

The occasion doubled as the midway checkpoint for the Early Warnings for All (EW4All) initiative, launched by Guterres in 2022 to ensure every person on Earth is protected by life-saving warning systems by 2027.

WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo issued a “Call to Action,” urging all countries to close early warning gaps through expanded observation networks, strengthened hydrological services, and community-level outreach. “Every dollar invested in early warning saves up to fifteen in disaster losses,” she said.

Saulo cautioned that despite major progress—108 countries now operate multi-hazard warning systems—the world’s poorest remain the least protected. Disaster mortality rates are six times higher in countries with limited early warning coverage.

A 75-Year Legacy of Science for Action

Marking 75 years since it became a UN specialized agency, WMO used its Extraordinary Congress to reaffirm global cooperation in weather, water, and climate monitoring.

President Abdulla al Mandous praised Guterres for embedding early warning systems into the international climate agenda: “Early warnings are now recognized at the highest levels as cost-effective, life-saving, and cross-cutting solutions that reduce risk and advance development,” he said.

Guterres urged three urgent priorities to achieve universal coverage: integrating early warnings across governance structures, boosting finance and debt relief for vulnerable nations, and aligning national climate plans to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C.

“Every life lost to disaster is one too many,” he said. “With science, solidarity, and political resolve, we can ensure a safer planet for all.”

Society

Understanding AI: The Science, Systems, and Industries Powering a $3.6 Trillion Future

Explore how artificial intelligence is transforming finance, automation, and industry — and what the $3.6 trillion AI boom means for our future

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a major point of discussion and a defining technological frontier of our time. Experiencing remarkable growth in recent years, AI refers to computer systems capable of mimicking intelligent human cognitive abilities such as learning, problem-solving, critical decision-making, and creativity. Its ability to identify objects, understand human language, and act autonomously makes it increasingly feasible for industries like automotive manufacturing, financial services, and fraud detection.

As of 2024, the global AI market is valued at approximately USD 638.23 billion, marking an 18.6% increase from 2023, and is projected to reach USD 3,680.47 billion by 2034 (Precedence Research). North America leads this global growth with a 36.9% market share, dominated by the United States and Canada. The U.S. AI market alone is valued at around USD 146.09 billion in 2024, representing nearly 22% of global AI investments.

The Early Evolution of AI: From Reactive Machines to Learning Systems

Our understanding of AI has evolved through different models, each representing a step closer to mimicking human intelligence.

Reactive Machines: The First Generation

One of the earliest and most famous AI systems was IBM’s Deep Blue, the chess-playing computer that defeated world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997. Deep Blue was a reactive machine model, relying on brute-force algorithms that evaluated millions of possible moves per second. It could process current data and generate responses, but lacked memory or the ability to learn from past experiences.

Reactive machines are task-specific and cannot adapt to new or unexpected conditions. Despite these limitations, they remain integral to automation, where precision and repeatability are more important than learning—such as in manufacturing or assembly-line robotics.

Limited Memory AI: Learning from Experience

To overcome the rigidity of reactive machines, researchers developed Limited Memory AI, a model that can store and recall past data to make more informed decisions. This model powers technologies such as self-driving cars, which constantly analyze road conditions, objects, and obstacles, using stored data to adjust their behaviour.

Limited Memory AI is also valuable in financial forecasting, where it uses historical market data to predict trends. However, its memory capacity is still finite, making it less suited for complex reasoning or tasks like Natural Language Processing (NLP) that require deeper contextual understanding.

Theoretical Models: Towards Human-Like Intelligence

Theory of Mind AI

The next conceptual step is Theory of Mind AI, a model designed to understand human emotions, beliefs, and intentions. This approach aims to enable AI systems to interact socially with humans, interpreting emotional cues and behavioral patterns.

Researchers like Neil Rabinowitz from Google DeepMind have developed early prototypes such as ToMnet, which attempts to simulate aspects of human reasoning. ToMnet uses artificial neural networks modeled after brain function to predict and interpret behavior. However, replicating the complexity of human mental states remains a distant goal, and these systems are still largely experimental.

Self-Aware AI: The Future Frontier

The ultimate ambition of AI research is self-aware AI — systems that possess conscious awareness and a sense of identity. While this remains speculative, the potential applications are vast. Self-aware AI could revolutionize fields like environmental management, creating bots capable of predicting ecosystem changes and implementing conservation strategies autonomously.

In education, self-aware systems could understand a student’s cognitive style and deliver personalized learning experiences, adapting dynamically to each learner.

However, replicating human self-awareness is extraordinarily complex. The human brain’s intricate memory, emotion, and decision-making systems remain only partially understood. Additionally, self-aware AI raises profound ethical and privacy concerns, as such systems would require massive amounts of sensitive data. Strict guidelines for data collection, storage, and usage would be essential before such systems could be deployed responsibly.

Artificial Intelligence in the Financial Services Industry

The financial sector has undergone a massive transformation powered by AI-driven analytics, automation, and predictive intelligence. AI enhances Corporate Performance Management (CPM) by improving speed and precision in financial planning, investment analysis, and risk management.

Natural Language Processing and Automation

Leading financial firms such as JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs employ Natural Language Processing (NLP) — AI systems that understand human language — to streamline customer interaction and analyze market information. NLP tools like chatbots handle millions of customer queries efficiently, while advanced systems process unstructured text data from financial reports and news sources to inform investment decisions.

Paired with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and document parsing, NLP systems can convert scanned or image-based documents into machine-readable text, accelerating compliance checks, fraud detection, and financial forecasting.

However, the accuracy of NLP models depends on the quality and diversity of training data. Biased or incomplete data can lead to errors in analysis, potentially influencing high-stakes financial decisions.

Generative AI in Finance

Another major shift in finance comes from Generative AI, a branch of AI that creates new content — including text, images, videos, and even financial models — based on learned patterns. Using Large Language Models (LLMs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), these systems simulate complex financial scenarios, improving fraud detection and stress testing.

For instance, PayPal and American Express use generative AI to simulate fraudulent transaction patterns, strengthening their security systems. Transformers — deep learning architectures behind tools like OpenAI’s GPT — enable these models to understand and generate human-like language, allowing them to summarize extensive reports, produce research briefs, and assist analysts in decision-making.

Yet, Generative AI also presents challenges. It can be manipulated through adversarial attacks, producing misleading or biased outputs if trained on flawed data. Ensuring transparency and fairness in training datasets remains critical to prevent discriminatory outcomes, especially in credit scoring and loan assessment.

AI and Automation: Revolutionizing Industry Operations

Artificial Intelligence has become a cornerstone of intelligent automation (IA), reshaping business process management (BPM) and robotic process automation (RPA). Traditional RPA handled repetitive, rule-based tasks, but with AI integration, these systems can now manage complex workflows that require contextual decision-making.

AI-driven automation enhances productivity, reduces operational costs, and increases accuracy. For example, in manufacturing, AI-enabled systems perform predictive maintenance by analyzing sensor data to detect machinery issues before failures occur, minimizing downtime and extending equipment lifespan.

In the automotive sector, AI-powered machine vision systems inspect car components with higher accuracy than human inspectors, ensuring consistent quality and safety. These innovations make automation not only efficient but also economically advantageous for large-scale industries.

Machine Learning: The Engine of Artificial Intelligence

At the heart of AI lies Machine Learning (ML) — algorithms that allow computers to learn from data and improve over time without explicit programming. Three fundamental ML models underpin most modern AI applications: Decision Trees, Linear Regression, and Logistic Regression.

Decision Trees

Decision trees simplify complex decision-making processes into intuitive, branching structures. Each branch represents a decision rule, and each leaf node gives an outcome or prediction. This makes them powerful tools for disease diagnosis in healthcare and credit risk assessment in finance. They handle both numerical and categorical data, offering transparency and interpretability.

Linear Regression

Linear regression models relationships between one dependent and one or more independent variables, making it useful for predictive analytics such as stock price forecasting. It applies mathematical techniques like Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) or Gradient Descent to optimize prediction accuracy. Its simplicity, efficiency, and scalability make it ideal for large datasets.

Logistic Regression

While linear regression predicts continuous outcomes, logistic regression is used for classification problems — determining whether an instance belongs to a particular category (e.g., yes/no, fraud/genuine). It calculates probabilities between 0 and 1 using a sigmoid function, providing fast and interpretable results. Logistic regression is widely used in healthcare (disease prediction) and finance (loan default assessment).

Types of Machine Learning Algorithms

Machine Learning can be broadly classified into Supervised, Unsupervised, and Reinforcement Learning — each suited for different problem types.

Supervised Learning

In supervised learning, algorithms train on labelled datasets to identify patterns and make predictions. Once trained, they can generalize to new, unseen data. Applications include spam filtering, voice recognition, and image classification.

Supervised models handle both classification (categorical predictions) and regression (continuous predictions). Their strength lies in high accuracy and reliability when trained on quality data.

Unsupervised Learning

Unsupervised learning, in contrast, deals with unlabelled data. It identifies hidden patterns or groupings within datasets, commonly used in customer segmentation, market basket analysis, and anomaly detection.

By autonomously discovering relationships, unsupervised learning reduces human bias and is valuable in exploratory data analysis.

Reinforcement Learning (Optional Expansion)

While not yet as mainstream, reinforcement learning trains algorithms through trial and error, rewarding desired outcomes. It is foundational in robotics, autonomous systems, and game AI — including the systems that now outperform humans in complex strategic games like Go or StarCraft.

Ethical and Societal Considerations of AI

Despite its transformative potential, AI raises significant ethical and privacy challenges. Issues such as algorithmic bias, data exploitation, and job displacement are increasingly at the forefront of public discourse.

Ethical AI demands transparent data practices, accountability in algorithm design, and equitable access to technology. Governments and academic institutions, including Capitol Technology University (captechu.edu), emphasize developing AI systems that align with social good, human rights, and sustainability.

Furthermore, the rise of generative AI has intensified debates about content authenticity, intellectual property, and deepfake misuse, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive AI regulation.

A Technology Still in Transition

Artificial Intelligence stands at the intersection of opportunity and uncertainty. From Deep Blue’s deterministic algorithms to generative AI’s creative engines, the technology has redefined industries and continues to evolve at an unprecedented pace.

While self-aware AI and full cognitive autonomy remain theoretical, the rapid integration of AI across industries signals an irreversible shift toward machine-augmented intelligence. The challenge ahead is ensuring that this evolution remains ethical, inclusive, and sustainable — using AI to enhance human potential, not replace it.

References

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Market Size to Reach USD 3,680.47 Bn by 2034 – Precedence Research

- What is AI, how does it work and what can it be used for? – BBC

- 10 Ways Companies Are Using AI in the Financial Services Industry – OneStream

- The Transformative Power of AI: Impact on 18 Vital Industries – LinkedIn

- What Is Artificial Intelligence (AI)? – IBM

- The Ethical Considerations of Artificial Intelligence – Capitol Technology University

- What is Generative AI? – Examples, Definition & Models – GeeksforGeeks

Society

The Dragon and the Elephant Dance for a Cleaner World

New reports from the IEA and Ember show that China and India are leading a global turning point — where renewables now outpace fossil fuels.

In late September, EdPublica reported an inspirational story from Perinjanam, a quiet coastal village in the South Indian state Kerala, where rooftops gleam with solar panels and homes have turned into micro power plants. It was a story of how ordinary citizens, through community effort and government support, took part in a just energy transition.

That local story, seemingly small, was in fact a mirror of a far bigger movement unfolding worldwide. Now, two major global reports–one from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and another from the independent think tank Ember–confirm that the world is entering a decisive new phase in its energy transformation. Together, their findings show that 2025 is shaping up to be the turning point year: the moment when renewables not only surpassed coal but began meeting all new global electricity demand. The year will likely be remembered as the moment when the global energy transition stopped being a promise and became a measurable reality — led by the two Asian giants, China and India.

The Global Picture: IEA’s Big Forecast

‘The IEA’s Renewables 2025’ report, released on October 7, paints an extraordinary picture of growth and possibility. Despite global headwinds — including high interest rates, supply chain bottlenecks, and policy shifts — renewable energy capacity is projected to more than double by 2030, adding 4,600 gigawatts (GW) of new renewable power.

To grasp that number: it’s equivalent to building the entire current electricity generation capacity of China, the European Union, and Japan combined.

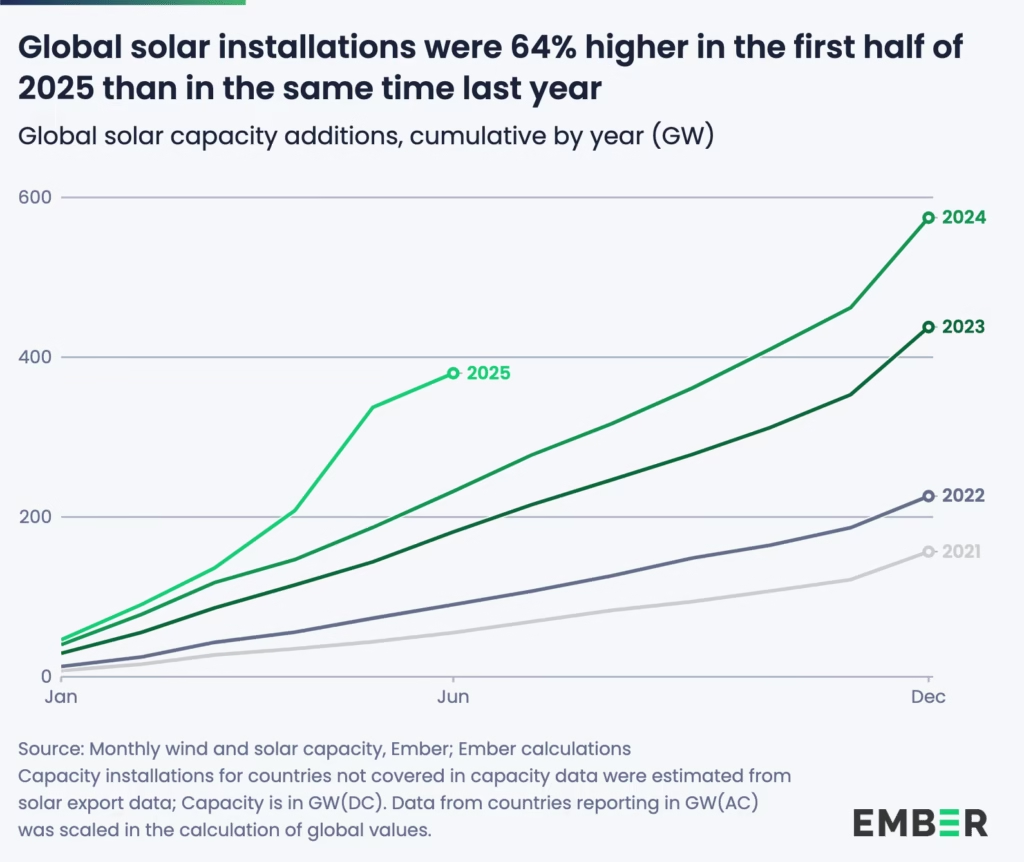

At the centre of this boom is solar photovoltaic (PV) technology, which will account for around 80% of the total growth. The IEA calls solar “the backbone of the energy transition,” driven by falling costs, faster permitting processes, and widespread adoption across emerging economies. Wind, hydropower, bioenergy, and geothermal follow closely behind, expanding capacity even as global systems adapt to higher shares of variable power.

“The growth in global renewable capacity in the coming years will be dominated by solar PV – but with wind, hydropower, bioenergy and geothermal all contributing, too,” said Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the IEA. “As renewables’ role in electricity systems rises in many countries, policymakers need to play close attention to supply chain security and grid integration challenges.”

The IEA forecasts particularly rapid progress in emerging markets. India is set to become the second-largest renewables growth market in the world, after China, reaching its ambitious 2030 targets comfortably. The report highlights new policy instruments — such as auction programs and rooftop solar incentives — that are spurring confidence across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

In India, the expansion of corporate power purchase agreements, utility contracts, and merchant renewable plants is also driving a quiet revolution, accounting for nearly 30% of global renewable capacity expansion to 2030.

At the same time, challenges remain. The IEA points to a worrying concentration of solar PV manufacturing in China, where over 90% of supply chain capacity for key components like polysilicon and rare earth materials is expected to remain by 2030.

Grid integration is another bottleneck. As solar and wind grow, many countries are already facing curtailments — when renewable power cannot be fed into the grid due to overload or mismatch in demand. The IEA stresses the need for urgent investment in transmission infrastructure, storage technologies, and flexible generation to prevent this momentum from being wasted.

Evidence on the Ground

If the IEA’s report is a map of where we’re going, Ember’s Mid-Year Global Electricity Review 2025 shows where we are right now — and the signs are unmistakable.

Ember’s data, covering the first half of 2025, reveals that solar and wind met all of the world’s rising electricity demand — and even caused a slight decline in fossil fuel generation. It’s a first in recorded history.

“We are seeing the first signs of a crucial turning point,” said Małgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, Senior Electricity Analyst at Ember. “Solar and wind are now growing fast enough to meet the world’s growing appetite for electricity. This marks the beginning of a shift where clean power is keeping pace with demand growth.”

Global electricity demand rose by 2.6% in early 2025, adding about 369 terawatt-hours (TWh) compared with the same period last year. Solar alone met 83% of that rise, thanks to record generation growth of 306 TWh, a year-on-year increase of 31%. Wind contributed another 97 TWh, leading to a net decline in both coal and gas generation.

Coal generation fell 0.6% (-31 TWh) and gas 0.2% (-6 TWh), marking a combined fossil decline of 0.3% (-27 TWh). As a result, global power sector emissions fell by 0.2%, even as demand continued to grow.

Most significantly, for the first time ever, renewables generated more power than coal. Renewables supplied 5,072 TWh, overtaking coal’s 4,896 TWh — a symbolic but historic milestone.

“Solar and wind are no longer marginal technologies — they are driving the global power system forward,” said Sonia Dunlop, CEO of the Global Solar Council. “The fact that renewables have overtaken coal for the first time marks a historic shift.”

China and India Lead the Way

The two reports together highlight that the epicenter of the clean energy shift is now in Asia.

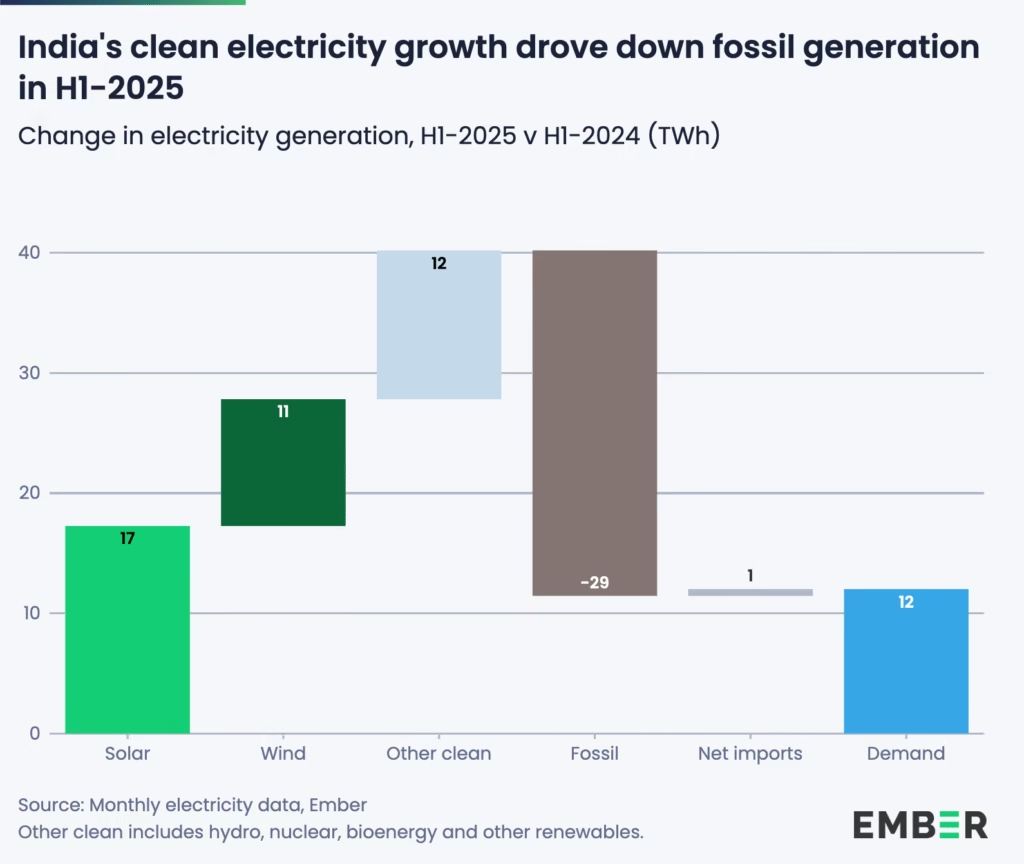

According to Ember, China’s fossil generation fell by 2% (-58.7 TWh) in the first half of 2025, as clean power growth outpaced rising electricity demand. Solar generation jumped 43% (+168 TWh), and wind grew 16% (+79 TWh), together helping cut the country’s power sector emissions by 1.7% (-47 MtCO₂).

Meanwhile, India’s fossil fuel decline was even steeper in relative terms. Solar and wind generation grew at record pace — solar by 25% (+17 TWh) and wind by 29% (+11 TWh) — while electricity demand rose only 1.3%, far slower than in 2024. The result: coal use dropped 3.1% (-22 TWh) and gas by 34% (-7 TWh), leading to an estimated 3.6% fall in power sector emissions.

For both countries, these numbers align closely with the IEA’s projections. Together, China and India are now the primary engines of renewable capacity growth, demonstrating how large emerging economies can pivot toward clean energy while maintaining development momentum.

Setbacks Elsewhere

Yet progress is uneven. In the United States and European Union, fossil generation actually rose in early 2025.

In the U.S., a 3.6% rise in demand outpaced clean power additions, leading to a 17% increase in coal generation (+51 TWh), though gas use fell slightly. The EU also saw higher gas and coal use due to weaker wind and hydro output.

The IEA attributes part of this slowdown to policy uncertainty, especially in the U.S., where an early phase-out of federal tax incentives has reduced renewable growth expectations by almost 50% compared to last year’s forecast. Europe’s problem is different — a mature but strained grid facing seasonal fluctuations and low wind output.

These regional discrepancies underscore the IEA’s core message: achieving a clean power future isn’t just about building more solar farms, but about building smarter systems — integrated, flexible, and resilient.

Beyond Power

Both reports agree that while renewables are transforming electricity, their impact on transport and heating remains limited.

In transport, the IEA projects renewables’ share to rise modestly from 4% today to 6% in 2030, mostly through electric vehicles and biofuels. In heating, renewables are set to grow from 14% to 18% of global energy use over the same period.

These slower-moving sectors will define the next frontier of decarbonization — one where electrification, hydrogen, and new thermal storage technologies must play a greater role.

The Big Picture

Put together, the IEA’s forecasts and Ember’s real-world data signal that the clean energy transition has passed the point of no return.

Solar and wind are no longer simply catching up — they are now shaping global power dynamics. Their continued expansion is not only meeting new demand but beginning to displace fossil fuels outright.

“As costs of technologies continue to fall, now is the perfect moment to embrace the economic, social and health benefits that come with increased solar, wind and batteries,” said Ember’s Wiatros-Motyka.

Yet both agencies caution: to sustain this momentum, governments must expand grid capacity, diversify supply chains, and improve energy storage systems. Without these, the 2025 breakthrough could become a bottleneck.

A Symbol and a Signal

In a way, the world in 2025 looks a lot like Perinjanam did a few years ago — a place where optimism met obstacles, but the light won. What was once a village-scale transition is now a planetary transformation, proving that even small local models can foreshadow global change.

From Kerala’s rooftops to China’s vast solar parks, from India’s wind corridors to Africa’s mini-grids, the direction is unmistakable: the sun and wind are powering the next phase of human progress.

If 2024 was the year of warnings, 2025 is the year of evidence. The global energy system is finally tilting toward sustainability — not someday, but today.

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Know The Scientist6 months ago

Know The Scientist6 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoRemembering S.N. Bose, the underrated maestro in quantum physics

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoWhy the Arts Matter As Much As Science or Math

-

Earth5 months ago

Earth5 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”