Learning & Teaching

Why is it important to understand multiple intelligences?

Multiple intelligences is a theory about how the mind is organised and how it operates.

From the 19th century to the latter part of the 20th century, we believed that there was a single thing called general intelligence, and that an individual who is strong in one area is likely to be strong in other areas as well. It helped the teachers and parents judge their kids as smart or unintelligent, given their varying capacities of general intelligence.

In the early 1980s, US-based developmental psychologist Howard Gardner identified and substantiated that there are multiple intelligences within a human being, which shaped an entirely new thinking process and approach towards psychology, cognitive behaviour, and education. It was an appreciation of the multi-faceted nature of the mind. The theory gained traction on the premise that the concepts of individual learning styles and learning preferences should be prioritised. Teachers will gain a better understanding of how to optimise learning if they have better knowledge of both learning styles and multiple intelligences (MI).

Howard Gardner developed MI theory in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He presented the theory for the first time in his 1983 book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Gardner proposes the idea that we all have various levels of intelligence across a range of intellectual areas. His theory assumes significance in the context that when intelligence is measured, the most commonly used tests like standard verbal and non-verbal reasoning tests often do not allow those tested to demonstrate what they are really good at or where their intelligence lies.

Multiple intelligences theory implies that human beings possess several relatively independent computers; strength in one computer does not predict strengths or weaknesses of other computers.

According to Gardner, multiple intelligences is a theory about how the mind is organised and how it operates. He provides us a set of different individuals that we display more or less of, according to our particular intellectual make-up.

The nine intelligences Gardner gives us are linguistic, logical/mathematical, musical, spatial/visual, kinaesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, naturalistic, and existential. The first one is about the potential of a person with respect to all things literary and linguistic. Logical intelligence deals with mathematics and science, games of strategy, and any logic-based pursuits. Musical intelligence is the enjoyment of and capacity for music-listening, playing, and perhaps composing. Spatial intelligence is associated with images, drawing, construction games, and tactile puzzles such as jigsaws. In kinaesthetic intelligence, activities that involve touch and movement, dance, sports, and other practical activities gain significance. Interpersonal intelligence counts on the ability to interact effectively with others, communication, leadership, and the ability to empathise.

Intrapersonal is all about self-motivation and the awareness of one’s own feelings more than those of others. While naturalistic intelligence is the ability to recognise patterns and classifications in nature, existential intelligence deals with asking and examining questions on life, death, and absolute realities.

As mentioned at the beginning, these intelligences have a direct link to the way in which students’ learning takes place. For instance, someone with great interpersonal skills would be most likely to learn effectively in a social situation where relating ideas and knowledge to others can be encouraged. The opposite is the case for a student with great intrapersonal skills and low interpersonal strength.

So, before we conclude, why is Multiple Intelligences theory still relevant today? The answer seems simple when you compare intelligences to computers. As Gardner once said, belief in a singular intelligence implies that humans possess a single general-purpose computer, which can perform well (high IQ), average (normal IQ) or poorly (low IQ). Multiple intelligences theory implies that human beings possess several relatively independent computers; strength in one computer does not predict strengths or weaknesses of other computers.

When it comes to learning, using the different intelligences to teach a concept gives each of your diverse learners a chance to succeed at learning. Learning through drawing and puzzles will benefit the learner with strong visual-spatial intelligence. Students with a strength in linguistic intelligence would do well with a written report over a reading assignment. Teaching to a student’s strength helps increase learning success.

Learning & Teaching

What’s Your Learning Superpower? Here’s How to Find It

Let’s dive into the Honey-Mumford and VAK (Visual, Auditory, Kinaesthetic) models—two of education’s most influential maps for personalizing the learning journey.

Imagine being dropped in a brand-new city where everyone speaks a different language. Some people grab a map and start drawing routes. Others listen intently to locals, some race into the streets to explore by doing, and a few quietly observe from a café, making notes. Which traveler are you? In the world of learning, discovering your “learning style” is like finding your unique superpower—the secret key to faster, deeper, more enjoyable learning.

How do you unlock your own learning?

Let’s dive into the Honey-Mumford and VAK (Visual, Auditory, Kinaesthetic) models—two of education’s most influential maps for personalizing the learning journey.

Why Learning Styles Matter (and Why They Change)

It’s important to realize learning preferences aren’t set in stone. Just as a traveler adapts to new cities, learners shift styles based on the challenge. Most of us lean toward one or two favourite modes, but flexibility is key. According to Peter Honey and Alan Mumford’s classic model, being able to “wear all four hats” is crucial for mastering new skills. If you stubbornly avoid certain ways of learning, you may unknowingly tie your own shoelaces together.

Here’s how the four Honey-Mumford learning styles look in action:

Activist: The daredevils of learning! Activists live for new experiences. They’re first to leap into workshops, group activities, and hands-on challenges. They learn best when they’re doing, discussing, and exploring.

Reflector: These learners are the wise owls. Quietly observing first, they watch from every angle, gathering information before jumping in. Their superpower? Drawing connections and insights from deep thinking.

Theorist: Think of the philosophers and scientists. Theorists want the “why” behind everything. They thrive on models, structures, and clear explanations, asking, “Does this make sense?” and “Is there a theory here?”

Pragmatist: These are the builders and fixers. Pragmatists want practical, real-world application. “How can I use this?” is their guiding question. They flourish when they’re solving problems and trying out ideas.

The Visual, Auditory, and Kinaesthetic Adventure

But wait—there’s more! According to neuro-linguistic programming and the globally popular VAK model, everyone navigates the world of knowledge in their own preferred “language”: seeing, hearing, or doing. Here’s how to spot yours:

Visual Learner: You see the world in pictures. Diagrams, charts, videos, and handouts light up your mind. If you sketch ideas or remember faces better than names, visual is your superpower.

Auditory Learner: Sound is your guide. You remember best what you hear—lectures, podcasts, discussions, even recording and replaying information. You may even talk aloud to “think.”

Kinaesthetic Learner: Your hands lead the way. You learn by doing. Whether painting, building, or physically working through problems, motion and touch fuel your brain.

So, How Do You Find Your Style?

No one is 100% one type. Like expert travelers, the best learners pack more than one compass. Educational researcher Niel Fleming expanded on these ideas, showing that all of us use a mix—sometimes favoring one “sense,” sometimes another. Being stuck with just one style can slow you down; flexibility makes the difference.

Educators, coaches, and students can all benefit by asking simple questions—”Do I remember better what I see, hear, or do?”—and using practical inventories from Honey, Mumford, or Fleming to discover strengths.

Want to unlock your learning superpower? Pay attention to how you most naturally enjoy, remember, and apply new information—and don’t be afraid to experiment with new learning adventures. Your secret strength might just surprise you.

Learning & Teaching

What India’s Foundational Learning Crisis Is Really Telling Us About Math

“They Can Count in the Market, But Not in the Classroom”: What India’s Foundational Learning Crisis Is Really Telling Us

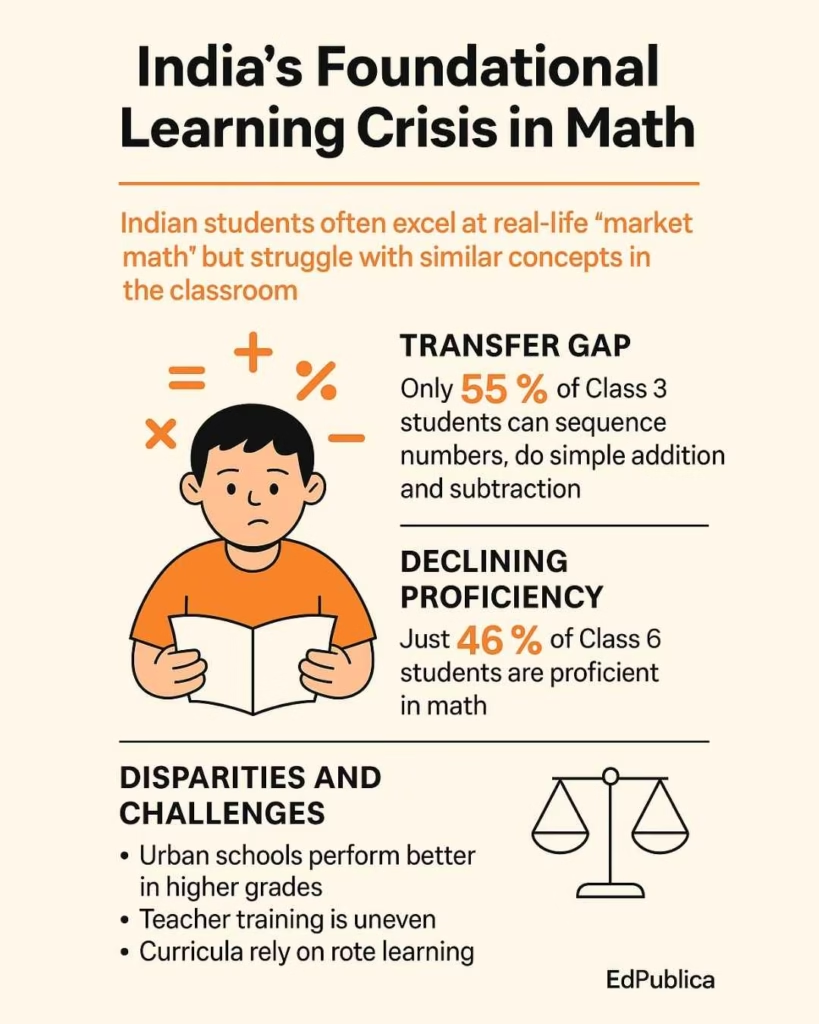

Earlier this year, EdPublica reported on an unsettling truth emerging from a collaborative study by MIT and Indian education researchers: Indian children demonstrate impressive mathematical ability when navigating real-life situations—like calculating change in a vegetable market—but often fail when asked to solve similar problems in the classroom. The findings struck a chord, revealing a deep fracture between what children learn and how they learn it.

Now, new data from the government-backed PARAKH Rashtriya Sarvekshan 2024 confirms the broader scale of that crisis. Together, the two reports offer a sobering diagnosis of foundational learning in India—and an urgent call to rethink how education is delivered.

The transfer gap: Street-smart, classroom-stranded

In the February study we reported on, researchers observed that children who work in markets—some out of necessity—could perform complex mental arithmetic swiftly and accurately. But the same children struggled with formal school problems like structured division or textbook subtraction. Meanwhile, their peers in schools did well on written math tests but faltered when asked to apply the same concepts in spontaneous, real-life situations.

This disconnect isn’t just about math—it’s about transferability. What good is education if it doesn’t translate beyond the exam sheet?

PARAKH’s alarming snapshot

The Performance Assessment, Review, and Analysis of Knowledge for Holistic Development (PARAKH) is India’s new national assessment platform launched under the National Education Policy 2020. Managed by the NCERT in collaboration with CBSE and overseen by the Ministry of Education, PARAKH represents a shift away from traditional rote exams to competency-based evaluation.

Its first large-scale survey, conducted in December 2024 across 23 lakh students from Classes 3, 6, and 9, paints a picture that is both revealing and troubling.

In Class 3, only 55% of students could correctly sequence numbers up to 99 or perform simple addition and subtraction. By Class 6, just 53% had mastered multiplication tables up to 10. Math proficiency hovered at 46% overall. The pattern held across language and environmental studies as well.

Perhaps most alarming is the steady decline in foundational ability as students progress. What begins as a fragile grasp in Class 3 becomes a gaping void by Class 9.

Where you study matters

The data also revealed a curious twist: in Class 3, rural students marginally outperformed their urban peers in both math and language. But by Class 6 and 9, the urban students pulled ahead decisively. It suggests that whatever edge rural systems may offer in the early years is quickly lost due to resource constraints, poor infrastructure, or lack of academic support.

Meanwhile, central government-run schools—such as Kendriya Vidyalayas—consistently outperformed state-run and aided schools, particularly in mathematics. The gaps are not just between regions, but embedded within the structure of the system itself.

A system teaching at children, not with them

What both the MIT study and the PARAKH survey show is this: India’s education system, despite enormous progress in enrolment and infrastructure, still hasn’t solved the puzzle of meaningful learning. It teaches children how to arrive at the “right” answer on paper, but not how to reason, estimate, or solve problems in the real world.

This isn’t simply a curriculum issue—it’s pedagogical. Teachers often default to formulas and procedures, driven by syllabus completion and exam pressures. Conceptual understanding, critical thinking, and the space to make mistakes are rare in crowded classrooms with little support for differentiated learning.

Moving from numbers to nuance

To its credit, the Ministry of Education has recognized this crisis. The PARAKH framework is designed not just to assess but to inform change. Its next phase will involve teacher workshops, state- and district-level consultations, and detailed “health reports” of learning outcomes.

A country with one of the youngest populations in the world cannot afford a foundational crisis

But meaningful change will require more than data. It demands political will, sustained investment in teacher training, reduced pupil–teacher ratios, and a shift in classroom culture. Most of all, it requires a rethinking of what education is meant to do—not just pass students from one grade to the next, but prepare them for life.

The stakes couldn’t be higher

A country with one of the youngest populations in the world cannot afford a foundational crisis. Poor learning in early years compounds over time, leading to disengagement, dropout, and economic vulnerability. The students struggling to divide 96 by 8 today are tomorrow’s workforce—and the gaps in their learning will define the future of the nation.

If India wants to reap its much-discussed demographic dividend, it must invest in the one thing that can turn numbers into citizens, and citizens into leaders: deep, transferable learning.

Learning & Teaching

Why the Arts Matter As Much As Science or Math

It is time to recalibrate. To reclaim the arts not as an extra, but as essential. Not just because they improve test scores—but because they improve lives.

A decade ago, a quiet crisis was unfolding in classrooms across the world—a crisis that continues to deepen. As the race to master STEM subjects quickens and strategic thinking becomes the gold standard of education, another essential pillar of learning is being pushed to the periphery: the arts.

In corridors where brush strokes once danced, and where theatre, music and storytelling ignited young minds, silence now lingers. Time and resources are reallocated. Arts periods shrink. Drama rooms gather dust. And with every such decision, we inch closer to a narrow, fragmented vision of what it means to educate a human being.

This cultural shift—palpable in countries like India—has been unsettling for educators and researchers who have long argued that art is not an elective luxury, but an essential ingredient of a well-rounded education. One such voice is that of Dr. Ellen Winner, a leading scholar of arts education, who warned in an interview with this author nine years ago: “When schools cut short the time reserved for the arts and redirect it to what they call ‘important’ subjects, they’re not just risking the future of potential artists. They’re losing out on the inventors, the empathetic leaders, the bold thinkers of tomorrow.”

Her message was clear. The arts do not merely decorate our cultural fabric—they weave it. Ellen Winner, a leading expert in the psychology of art, is Professor Emerita of Psychology at Boston College and a Senior Research Associate at Project Zero. She is the author of five books, including Invented Worlds (1982), The Point of Words (1988), Gifted Children (1996), How Art Works (2019), and An Uneasy Guest in the Schoolhouse (2022). She has also co-authored five influential titles in arts education, notably the Studio Thinking series and The Child as Visual Artist (2022).

More Than a Side Show

To ask, “What is the role of the arts in shaping a person?” is to ask what kind of world we want to build. For centuries, societies have turned to art not just for beauty, but for insight—for truth. From ancient cave paintings to Renaissance frescoes to street murals that challenge injustice today, art has never been a passive pursuit. It has always spoken, always provoked, always taught.

And yet, as Dr. Winner noted in our conversation, “The arts are the only school subjects constantly required to prove their usefulness.”

Imagine applying the same standard to history, or even to sports. Suppose a school coach claimed that playing baseball boosts students’ math scores due to statistical scoring. If researchers debunked the claim, would school boards eliminate baseball from the curriculum? Of course not. Because we instinctively know that athletics builds discipline, teamwork, resilience. That it matters. So why not extend the same understanding to the arts?

Beyond the Test Scores

It is tempting—and common—for policymakers to justify the arts in terms of their “spillover effects” on math or reading. And indeed, there is research that shows a correlation: students exposed to the arts tend to perform better across disciplines. But relying solely on this line of defense, Dr. Winner cautioned, is dangerous.

The arts are not new. They have outlived empires. They have inspired revolutions. And they have told the stories of civilizations long after their rulers and battles were forgotten

“Arts education must not be justified only by its secondary benefits,” she said. “If we do that, we grant permission for it to be cut whenever those benefits don’t show up clearly on a chart.”

The truth is, arts education offers something far deeper. It cultivates imagination, nurtures curiosity, and fosters emotional intelligence. It teaches us to live with ambiguity, to see from multiple perspectives, to create from chaos. These are not fringe skills. These are survival skills—in life, and in leadership.

A Legacy We Must Honour

The arts are not new. They have outlived empires. They have inspired revolutions. And they have told the stories of civilizations long after their rulers and battles were forgotten.

Dr. Winner, summarizing a lifetime of scholarship, told me this:

“Let’s bet on history. Cultures have always been remembered by their art. The arts predate the sciences. Education that excludes them is impoverished—and it leads to an impoverished society.”

We would never teach a child only numbers and grammar and send them out into the world. Yet when we sideline the arts, that’s exactly what we do. We deny them the tools to feel deeply, to question power, to imagine alternatives. We deny them the full experience of being human.

Looking ahead

This is not a plea for token inclusions. It is a call for equal footing. The arts must not sit at the kiddie table of education, forever proving their worth. They are the worth. Just as we revere science for its logic and discovery, we must revere art for its meaning and soul.

It is time to recalibrate. To reclaim the arts not as an extra, but as essential. Not just because they improve test scores—but because they improve lives.

Because in the end, we are remembered not for how efficiently we solved equations—but for the songs we sang, the stories we told, and the visions we dared to paint on the canvas of our times.

-

Space & Physics5 months ago

Space & Physics5 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Earth6 months ago

Earth6 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoDid JWST detect “signs of life” in an alien planet?

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

-

Society6 months ago

Society6 months agoRabies, Bites, and Policy Gaps: One Woman’s Humane Fight for Kerala’s Stray Dogs