The Sciences

Cheetah runs faster because of its physical ‘sweet spot’

“The key to our model is understanding that maximum running speed is constrained both by how fast muscles contract, as well as by how much they can shorten during a contraction,” says a scientist.

It’s common knowledge that medium-sized animals like cheetahs, tigers or even dogs are known to be faster than bigger animals like elephants, or even smaller ants. However, there are exceptions.

An interdisciplinary team of scientists provide a biomechanical explanation – combining biology with mechanics (as in physics). Apparently, their findings can inform robot designs, inspired by animal biomechanics.

“The key to our model is understanding that maximum running speed is constrained both by how fast muscles contract, as well as by how much they can shorten during a contraction,” said Professor Christofer Clemente, a biomechanics researcher from University of the Sunshine Coast and The University of Queensland, in Australia, in a press release.

Their paper was published in Nature Communications.

Their model uses two physical constraints. The first is by kinetic energy capacity, dictated by how fast do the muscles contract to generate forces much bigger than its own body weight. The second limit is by work capacity, dictated by how far the muscle contracts.

“For large animals like rhinos or elephants, running might feel like lifting an enormous weight, because their muscles are relatively weaker and gravity demands a larger cost,” said Peter Bishop, a biomechanics researcher at Harvard University, US. “As a result of both, animals eventually have to slow down as they get bigger.”

Apparently, this model offers an explanation as to why crocodiles, despite being medium-sized in a sense, aren’t so quick.

“One possible explanation for this may be that limb muscle is a smaller percentage of reptiles’ bodies, by weight, meaning that they hit the work limit at a smaller body weight, and thus have to remain small to move quickly,” said Taylor Dick, a biomechanics researcher at The University of Queensland, Australia.

Cheetahs, in contrast, which can attain a maximum speed of 65 km/hr, hits the physical sweet spot of 50 kg, when the two constraints set by kinetic energy and work capacity are equal.

The team tested their hypothesis against data gathered from 400 species of various sizes and body weights, including mites weighing just 0.1 mg, to six-tonne elephants.

The model doesn’t just offer explanations to known facts about speeds in present animals. It can be extrapolated to extinct animals such as dinosaurs, although with some caveats.

It predicts land animals heavier than 40 tonnes would be immobilized. The heaviest land animal, the African elephant, weighs around 6.6 tonnes. Although it was known that land-based dinosaurs such as the Patagotitan, possibly exceeded even 40 tonnes.

And this is where researchers erred on the side of caution, saying that their model was based on known anatomies of non-extinct animals. In fact, extinct giants might have evolved unique muscular anatomies, thus warranting more study.

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council, the international Human Frontier Science Program, and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.

The Sciences

Most Earthquake Energy Is Spent Heating Up Rocks, Not Shaking the Ground: New MIT Study Finds

How do earthquakes spend their energy? MIT’s latest research shows heat—not ground motion—is the main outcome of a quake, reshaping how scientists understand seismic risks

When an earthquake strikes, we experience its violent shaking on the surface. But new research from MIT shows that most of a quake’s energy actually goes into something entirely different — heat.

Using miniature “lab quakes” designed to mimic real seismic slips deep underground, geologists at MIT have, for the first time, mapped the full energy budget of an earthquake. Their study reveals that only about 10 percent of a quake’s energy translates into ground shaking, while less than 1 percent goes into fracturing rock. The vast majority — nearly 80 percent — is released as heat at the fault, sometimes creating sudden spikes hot enough to melt surrounding rock.

“These results show that what happens deep underground is far more dynamic than what we feel on the surface,” said Daniel Ortega-Arroyo, a graduate researcher in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, in a media statement. “A rock’s deformation history — essentially its memory of past seismic shifts — dictates how much energy ends up in shaking, breaking, or heating. That history plays a big role in determining how destructive a quake can be.”

The team’s findings, published in AGU Advances, suggest that understanding a fault zone’s “thermal footprint” might be just as important as recording surface tremors. Laboratory-created earthquakes, though simplified models of natural ones, provide a rare window into processes that are otherwise impossible to observe deep within Earth’s crust.

MIT researchers created the “microshakes” by applying immense pressures to samples of granite mixed with magnetic particles that acted as ultra-sensitive heat gauges. By stacking the results of countless tiny quakes, they tracked exactly how the energy distributed among shaking, fracturing, and heating. Some events saw fault zones heat up to over 1,200 degrees Celsius in mere microseconds, momentarily liquefying parts of the rock before cooling again.

“We could never reproduce the full complexity of Earth, so we simplify,” explained co-author Matěj Peč, MIT associate professor of geophysics. “By isolating the physics in the lab, we can begin to understand the mechanisms that govern real earthquakes — and apply this knowledge to better models and risk assessments.”

The work also provides a fresh perspective on why some regions remain vulnerable long after previous seismic activity. Past quakes, by altering the structure and material properties of rocks, may influence how future ones unfold. If researchers can estimate how much heat was generated in past quakes, they might be able to assess how much stress still lingers underground — a factor that could refine earthquake forecasting.

The study was conducted by Ortega-Arroyo and Peč, along with colleagues from MIT, Harvard University, and Utrecht University.

Health

Giant Human Antibody Found to Act Like a Brace Against Bacterial Toxins

This synergistic bracing action gives IgM a unique advantage in neutralizing bacterial toxins that are exposed to mechanical forces inside the body

Our immune system’s largest antibody, IgM, has revealed a hidden superpower — it doesn’t just latch onto harmful microbes, it can also act like a brace, mechanically stabilizing bacterial toxins and stopping them from wreaking havoc inside our bodies.

A team of scientists from the S.N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences (SNBNCBS) in Kolkata, India, an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), made this discovery in a recent study. The team reports that IgM can mechanically stiffen bacterial proteins, preventing them from unfolding or losing shape under physical stress.

“This changes the way we think about antibodies,” the researchers said in a media statement. “Traditionally, antibodies are seen as chemical keys that unlock and disable pathogens. But we show they can also serve as mechanical engineers, altering the physical properties of proteins to protect human cells.”

Unlocking a new antibody role

Our immune system produces many different antibodies, each with a distinct function. IgM, the largest and one of the very first antibodies generated when our body detects an infection, has long been recognized for its front-line defense role. But until now, little was known about its ability to physically stabilize dangerous bacterial proteins.

The SNBNCBS study focused on Protein L, a molecule produced by Finegoldia magna. This bacterium is generally harmless but can become pathogenic in certain situations. Protein L acts as a “superantigen,” binding to parts of antibodies in unusual ways and interfering with immune responses.

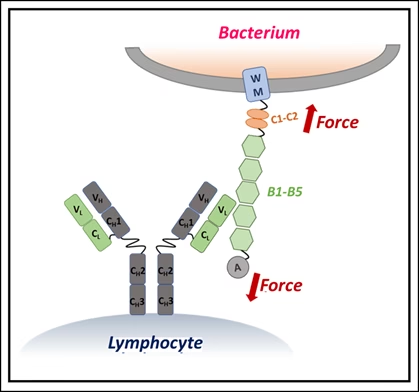

Using single-molecule force spectroscopy — a high-precision method that applies minuscule forces to individual molecules — the researchers discovered that when IgM binds Protein L, the bacterial protein becomes more resistant to mechanical stress. In effect, IgM braces the molecule, preventing it from unfolding under physiological forces, such as those exerted by blood flow or immune cell pressure.

Why size matters

The stabilizing effect depended on IgM concentration: more IgM meant stronger resistance. Simulations showed that this is because IgM’s large structure carries multiple binding sites, allowing it to clamp onto Protein L at several locations simultaneously. Smaller antibodies lack this kind of stabilizing network.

“This synergistic bracing action gives IgM a unique advantage in neutralizing bacterial toxins that are exposed to mechanical forces inside the body,” the researchers explained.

The finding highlights an overlooked dimension of how our immune system works — antibodies don’t merely bind chemically but can also act as mechanical modulators, physically disarming toxins.

Such insights could open a new frontier in drug development, where future therapies may involve engineering antibodies to stiffen harmful proteins, effectively locking them in a harmless state.

The study suggests that by harnessing this natural bracing mechanism, scientists may be able to design innovative treatments that go beyond traditional antibody functions.

Math

Researchers Unveil Breakthrough in Efficient Machine Learning with Symmetric Data

MIT researchers have developed the first mathematically proven method for training machine learning models that can efficiently interpret symmetric data—an advance that could significantly enhance the accuracy and speed of AI systems in fields ranging from drug discovery to climate analysis.

In traditional drug discovery, for example, a human looking at a rotated image of a molecule can easily recognize it as the same compound. However, standard machine learning models may misclassify the rotated image as a completely new molecule, highlighting a blind spot in current AI approaches. This shortcoming stems from the concept of symmetry, where an object’s fundamental properties remain unchanged even when it undergoes transformations like rotation.

“If a drug discovery model doesn’t understand symmetry, it could make inaccurate predictions about molecular properties,” the researchers explained. While some empirical techniques have shown promise, there was previously no provably efficient way to train models that rigorously account for symmetry—until now.

“These symmetries are important because they are some sort of information that nature is telling us about the data, and we should take it into account in our machine-learning models. We’ve now shown that it is possible to do machine-learning with symmetric data in an efficient way,” said Behrooz Tahmasebi, MIT graduate student and co-lead author of the new study, in a media statement.

The research, recently presented at the International Conference on Machine Learning, is co-authored by fellow MIT graduate student Ashkan Soleymani (co-lead author), Stefanie Jegelka (associate professor of EECS, IDSS member, and CSAIL member), and Patrick Jaillet (Dugald C. Jackson Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and principal investigator at LIDS).

Rethinking how AI sees the world

Symmetric data appears across numerous scientific disciplines. For instance, a model capable of recognizing an object irrespective of its position in an image demonstrates such symmetry. Without built-in mechanisms to process these patterns, machine learning models can make more mistakes and require massive datasets for training. Conversely, models that leverage symmetry can work faster and with fewer data points.

“Graph neural networks are fast and efficient, and they take care of symmetry quite well, but nobody really knows what these models are learning or why they work. Understanding GNNs is a main motivation of our work, so we started with a theoretical evaluation of what happens when data are symmetric,” Tahmasebi noted.

The MIT researchers explored the trade-off between how much data a model needs and the computational effort required. Their resulting algorithm brings symmetry to the fore, allowing models to learn from fewer examples without spending excessive computing resources.

Blending algebra and geometry

The team combined strategies from both algebra and geometry, reformulating the problem so the machine learning model could efficiently process the inherent symmetries in the data. This innovative blend results in an optimization problem that is computationally tractable and requires fewer training samples.

“Most of the theory and applications were focusing on either algebra or geometry. Here we just combined them,” explained Tahmasebi.

By demonstrating that symmetry-aware training can be both accurate and efficient, the breakthrough paves the way for the next generation of neural network architectures, which promise to be more precise and less resource-intensive than conventional models.

“Once we know that better, we can design more interpretable, more robust, and more efficient neural network architectures,” added Soleymani.

This foundational advance is expected to influence future research in diverse applications, including materials science, astronomy, and climate modeling, wherever symmetry in data is a key feature.

-

Space & Physics5 months ago

Space & Physics5 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Earth6 months ago

Earth6 months ago122 Forests, 3.2 Million Trees: How One Man Built the World’s Largest Miyawaki Forest

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoDid JWST detect “signs of life” in an alien planet?

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society4 months ago

Society4 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”

-

Society6 months ago

Society6 months agoRabies, Bites, and Policy Gaps: One Woman’s Humane Fight for Kerala’s Stray Dogs