Technology

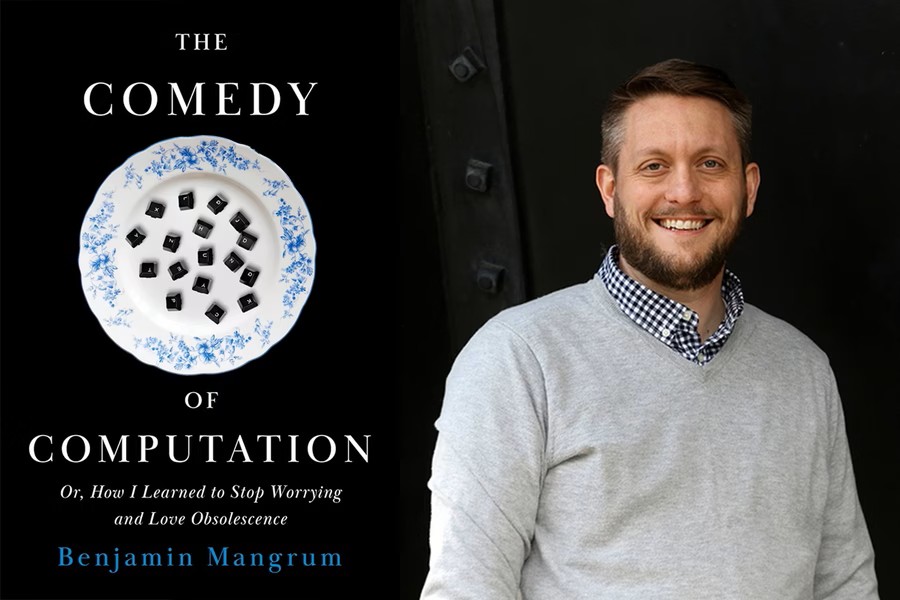

Humour, Humanity, and the Machine: A New Book Explores Our Comic Relationship with Technology

MIT scholar Benjamin Mangrum examines how comedy helps us cope with, critique, and embrace computing.

In a world increasingly shaped by algorithms, automation, and artificial intelligence, one unexpected tool continues to shape how we process technological change: comedy.

That’s the central argument of a thought-provoking new book by MIT literature professor Benjamin Mangrum, titled The Comedy of Computation: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Obsolescence, published this month by Stanford University Press. Drawing on literature, film, television, and theater, Mangrum explores how humor has helped society make sense of machines-and the humans who build and depend on them.

“Comedy makes computing feel less impersonal, less threatening,” Mangrum writes. “It allows us to bring something strange into our lives in a way that’s familiar, even pleasurable.”

From romantic plots to digital tensions

One of the book’s core insights is that romantic comedies-perhaps surprisingly-have been among the richest cultural spaces for grappling with our collective unease about technology. Mangrum traces this back to classic narrative structures, where characters who begin as obstacles eventually become partners in resolution. He suggests that computing often follows a similar arc in cultural storytelling.

“In many romantic comedies,” Mangrum explains, “there’s a figure or force that seems to stand in the way of connection. Over time, that figure is transformed and folded into the couple’s union. In tech narratives, computing sometimes plays this same role-beginning as a disruption, then becoming an ally.”

This structure, he notes, is centuries old-prevalent in Shakespearean comedies and classical drama-but it has found renewed relevance in the digital age.

Satirizing silicon dreams

In the book, Mangrum also explores what he calls the “Great Tech-Industrial Joke”-a mode of cultural humor aimed squarely at the inflated promises of the technology industry. Many of today’s comedies, from satirical shows like Silicon Valley to viral social media content, lampoon the gap between utopian tech rhetoric and underwhelming or problematic outcomes.

“Tech companies often announce revolutionary goals,” Mangrum observes, “but what we get is just slightly faster email. It’s a funny setup, but also a sharp critique.”

This dissonance, he argues, is precisely what makes tech such fertile ground for comedy. We live with machines that are both indispensable and, at times, disappointing. Humor helps bridge that contradiction.

The ethics of authenticity

Another recurring theme in The Comedy of Computation is the modern ideal of authenticity, and how computing complicates it. From social media filters to AI-generated content, questions about what’s “real” are everywhere-and comedy frequently calls out the performance.

“Comedy has always mocked pretension,” Mangrum says. “In today’s context, that often means jokes about curated digital lives or artificial intelligence mimicking human quirks.”

Messy futures, meaningful laughter

Ultimately, Mangrum doesn’t claim that comedy solves the challenges of computing-but he argues that it gives us a way to live with them.

“There’s this really complicated, messy picture,” he notes. “Comedy doesn’t always resolve it, but it helps us experience it, and sometimes, laugh through it.”

As we move deeper into an era of smart machines, digital identities, and algorithmic decision-making, Mangrum’s book reminds us that a well-placed joke might still be one of our most human responses.

(With inputs from MIT News)

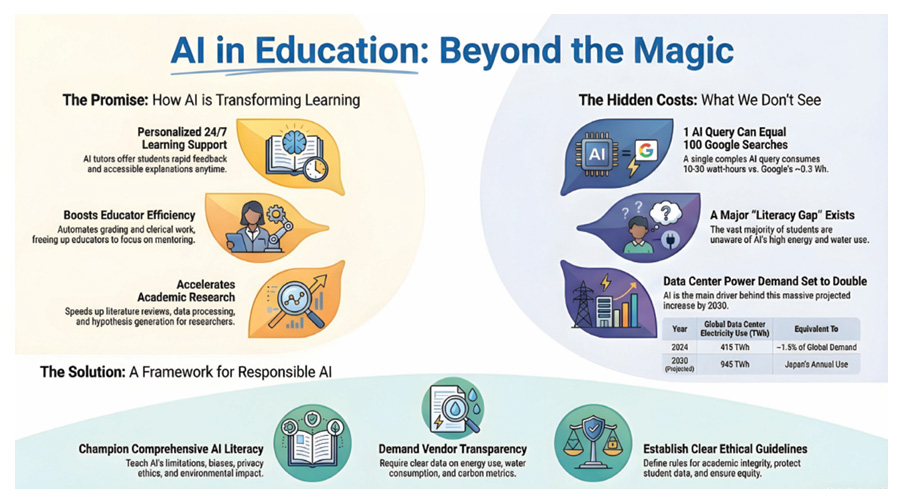

Technology

What does it mean to be genuinely ‘AI literate’?

A AI is transforming teaching, research and student life — enabling personalised learning, accelerating discovery and reshaping how campuses work. Yet beneath that convenience lie serious risks: opaque algorithms, rising plagiarism concerns, deepening inequities and an environmental footprint growing faster than most students or educators realise. Did you know? The IEA reports that global investment in data centres is now set to exceed global spending on oil — a stark reminder that “data is the new oil” is no longer a metaphor but an energy reality. EP lays out what true AI literacy must deliver, what institutions should demand from AI vendors, and how universities can build systems that are sustainable, transparent and accountable. The future of learning will be AI-enabled — but it must also be human centred, equitable and environmentally responsible

The rapid ascent of generative artificial intelligence is actively reshaping how we learn, create, and work. It offers a seductive promise of instant knowledge and effortless productivity, a modern-day magic trick available at our fingertips. But like any good magic act, the most important part of the illusion is what the audience doesn’t see. Behind the curtain of flawlessly formed paragraphs and instant data analysis lies a complex and often invisible world of ethical trade-offs and profound physical costs.

Consider the experience of a college student in 2025. When she asked an AI tutor for help with an essay, she watched in amazement as articulate, well-structured text appeared in seconds, complete with what looked like flawless references. The magic, however, quickly faded. As she began to engage critically with the output—tracing sources and questioning claims—she discovered some references were entirely fictitious, the reasoning was hollow, and the fluent prose was merely a sophisticated imitation of insight.

This student’s discovery is a microcosm of a much larger challenge. Her story moves us beyond the simple wonder of a new technology to the central question of our time: Are we truly prepared for the full consequences of the AI revolution? And in this new age, what does it mean to be genuinely “AI literate”?

Education Publica explores the good, the bad, and the hidden “ugly” of artificial intelligence. Our future depends not on whether if we use this transformative tool, but how we choose to use it—effectively, ethically, and with full awareness of its staggering environmental footprint. The path forward requires moving past the illusion and understanding the true cost of the bargain we are making.

The Promise and The Peril: AI’s Double-Edged Sword

To navigate the new AI landscape responsibly, we must first appreciate its dual nature. AI is neither a pure panacea nor an unmitigated threat; it is a powerful tool with the capacity for both transformative good and significant harm. Understanding this duality is the first step toward harnessing its potential while mitigating its inherent risks.

The Promise: A Revolution in Access and Efficiency

Proponents rightly point to a suite of transformative capabilities, particularly in making education more efficient and accessible. The key benefits are already becoming clear:

• Personalized Learning and Access: AI-powered tutors can provide students with 24/7 support, offering rapid feedback and accessible explanations. In a 2025 survey of undergraduates at a large US public university, students confirmed they value this immediate assistance. This technology holds particular promise for bringing personalized learning to underserved regions, such as India.

• Administrative Efficiency: For educators, AI can streamline time-consuming tasks like drafting lesson plans, summarizing readings, and assisting with grading. This frees up valuable time for them to focus on mentoring students and engaging in higher-order teaching.

• Research Acceleration: In academic and scientific fields, AI is a powerful catalyst. It can dramatically speed up literature reviews, process vast datasets, and even help generate new hypotheses, significantly boosting research productivity.

The Peril: The Costs to Integrity, Privacy, and Equity

Alongside its immense promise, AI introduces tangible risks that threaten the core tenets of academic inquiry and social equity. These perils require careful management and proactive policy.

1. Academic Integrity and Critical Thinking: The ease of generating text with AI presents a significant threat to academic integrity. A 2023 educational study warned that this makes it easier than ever for students to submit work they did not write. A more subtle danger is the phenomenon of AI “hallucinations”—false but convincingly presented information—which many students are ill-equipped to identify. Over-reliance on these tools risks weakening the essential skills of critical reasoning and research.

2. Privacy and Surveillance: The use of AI tools in education often involves storing vast amounts of student data on remote servers. Without robust policies and oversight, this sensitive information can be misused or profiled, creating significant privacy and surveillance risks.

3. The Widening Digital Divide: The benefits of AI are not universally accessible. Effective use requires stable internet, modern devices, and reliable electricity. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds who lack these resources risk falling even further behind, deepening existing educational and social inequities.

But these visible debates are a distraction from a far larger, physical cost that is being silently added to a global environmental ledger.

The Ugly: AI’s Invisible Environmental Footprint

While academia and industry wring their hands over plagiarism and bias, they remain wilfully blind to a far more inconvenient truth: the AI revolution is built on a foundation of staggering energy and water consumption. This isn’t an abstract cost; it’s a physical debt being charged to the planet with every query. This is the engine room of the illusion, an immense, energy-hungry global infrastructure that our collective failure to recognize is a critical flaw in our current understanding of the technology.

A Stark Literacy Gap

In a recent survey of over 30 undergraduate and postgraduate students from India, the UK, and Canada, a startling consensus emerged. These students, from diverse fields including engineering and humanities, were either enthusiastic or casual users of AI. Yet, with the exception of a single master’s scholar, not one of them had any meaningful understanding of AI’s physical and environmental footprint.

Their perception of AI was telling, revealing a profound disconnect between the digital tool and its physical reality.

Students frequently described AI as “free,” “virtual,” “weightless,” or “just code.” The notion that AI has a physical footprint—servers, cooling systems, chips, power draw—was almost entirely absent.

This gap represents a fundamental failure of AI literacy. Current education and discourse overwhelmingly focus on what AI does for us, not what it costs the planet. This blind spot is shaping policy and user behaviour at a moment when the stakes could not be higher.

Quantifying the Cost: From a Single Query to Global Demand

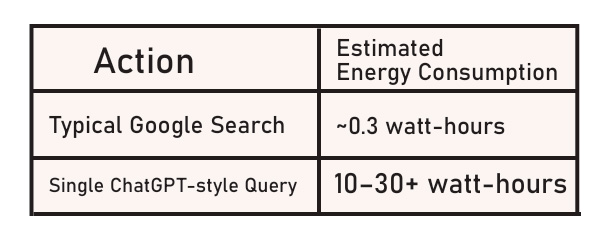

The feeling of “weightlessness” is an illusion. In terms of energy, a simple Google search and a generative AI query are worlds apart. The difference is not incremental; it is exponential.

The implication of this data is staggering: One long AI query can consume as much electricity as 30–100 Google searches. When multiplied by hundreds of millions of daily queries worldwide, this individual cost scales into a global crisis.

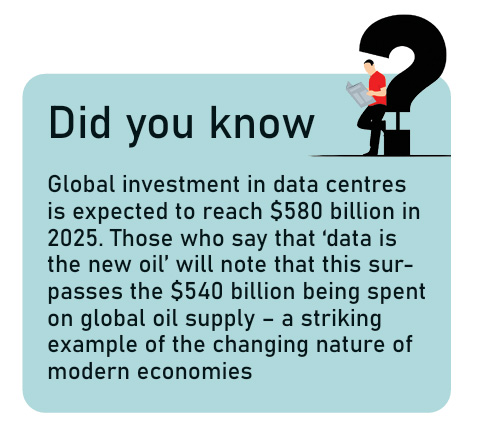

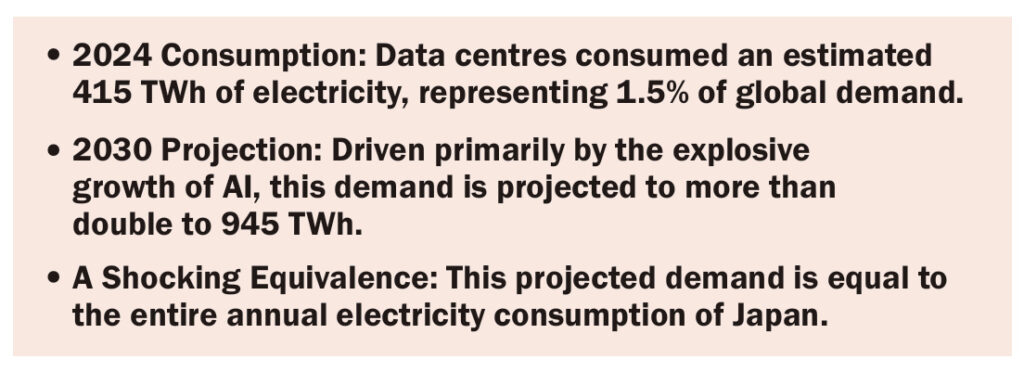

The scale of this shift is not theoretical; it is being meticulously tracked by global energy watchdogs, and their findings are alarming. The International Energy Agency (IEA) provides a chilling macro-level view of this trend:

• 2024 Consumption: Data centres consumed an estimated 415 TWh of electricity, representing 1.5% of global demand.

• 2030 Projection: Driven primarily by the explosive growth of AI, this demand is projected to more than double to 945 TWh.

• A Shocking Equivalence: This projected demand is equal to the entire annual electricity consumption of Japan.

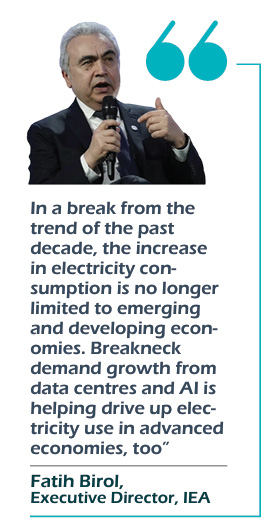

IEA’s recent analysis signals that AI is no longer just a technological tool but an energy-intensive industrial sector. Its electricity demands are now large enough to reshape consumption patterns in advanced economies and rival global investment in oil — a striking sign of the world’s transition into the “Age of Electricity.”

“Analysis in the World Energy Outlook has been highlighting for many years the growing role of electricity in economies around the world. Last year, we said the world was moving quickly into the Age of Electricity – and it’s clear today that it has already arrived,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol. “In a break from the trend of the past decade, the increase in electricity consumption is no longer limited to emerging and developing economies. Breakneck demand growth from data centres and AI is helping drive up electricity use in advanced economies, too. Global investment in data centres is expected to reach $580 billion in 2025. Those who say that ‘data is the new oil’ will note that this surpasses the $540 billion being spent on global oil supply – a striking example of the changing nature of modern economies.”

This global problem is coming to a head in nations where the balance between progress and sustainability is most delicate, nowhere more so than in India.

India at the AI Crossroads

India stands as the global epicenter of AI’s collision between digital ambition and physical limits. Its unique combination of immense economic opportunity, significant digital disparity, and acute environmental stress makes its approach to AI adoption a high-stakes paradox—and a bellwether for the entire developing world.

The Multi-Billion Dollar Promise

The economic incentives for embracing generative AI are enormous. An EY report estimates that by 2029-30, the adoption of GenAI could add US359 billion to US438 billion to India’s GDP, promising to accelerate growth and enhance productivity across the nation.

A Collision Course with Reality

Yet, this multi-billion-dollar vision, articulated by consultancies like EY, is on a direct collision course with the stark physical limitations outlined by energy and environmental analysts. For India, the promise of virtual wealth is tethered to the reality of stressed power grids and scarce water. Unregulated AI adoption threatens to exacerbate several pre-existing, systemic challenges:

• Digital Disparity: Large segments of the population still lack reliable access to the stable internet and modern devices required for AI-driven learning and work.

• Stressed Infrastructure: The nation’s electricity grids are already under significant strain, and the massive energy demands of AI data centres could push them to their limits.

• Environmental Scarcity: Many regions across India face severe water scarcity, a problem that would be intensified by the vast water requirements for cooling data centres.

• Budgetary Constraints: Public educational institutions operate on tight budgets, making it difficult to fund the necessary technological infrastructure and training for students and educators.

For India, blindly pursuing AI adoption is not a viable path. A deliberate, responsible, and human-centered framework is not just an option; it is an absolute necessity.

Redefining AI Literacy for a Sustainable Future

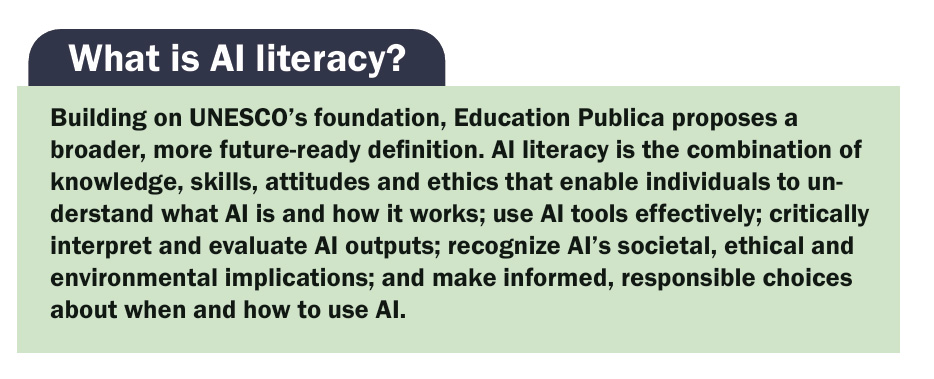

The challenges posed by AI, while significant, are not insurmountable. Addressing them requires a new, more comprehensive definition of AI literacy—one that is human-centered, ethically grounded, and environmentally accountable. The goal is not to restrict AI, but to build a foundation of trust and sustainability for its responsible integration into society. This requires a coordinated effort from educational institutions, organizations, and policymakers. According to UNESCO, AI literacy involves equipping learners and educators with a human-centred mindset, ethical awareness, conceptual understanding, and practical skills to use AI responsibly, understand its implications, and adapt as AI technologies evolve.

Building on UNESCO’s foundation, Education Publica proposes a broader, more future-ready definition: AI literacy is the integrated set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and ethical principles that enable individuals to understand what AI is and how it works; use AI tools effectively and safely; critically interpret and question AI outputs; recognise the societal, ethical, economic, and environmental impacts of AI systems; and make informed, responsible choices about when, why, and how to engage with AI.

For Educational Institutions and Organizations:

A proactive, principles-based approach is essential for navigating the complexities of AI integration. The following strategies provide a roadmap for responsible adoption:

1. Demand Vendor Transparency: Insist that AI providers not only disclose per-query energy data, carbon metrics, and water consumption but also provide “explainable AI” algorithms, helping users understand the “why” behind an output, not just the “what.”

2. Mandate Comprehensive AI Literacy: Implement formal courses covering not just AI use, but also its limitations, including inherent bias, hallucination risks, data privacy ethics, and its full environmental impact.

3. Establish Clear Ethical Guidelines: Develop and enforce robust academic integrity policies that explicitly define where AI is allowed (e.g., for brainstorming), allowed with declaration (e.g., for drafting assistance), or prohibited (e.g., in exams).

4. Protect Equity: Ensure students without reliable access to technology are not disadvantaged by maintaining viable offline alternatives for key academic activities and assessments.

5. Foster a Culture of Innovation and Inquiry: Beyond just mandating courses, institutions must build a culture that encourages experimentation and critical feedback loops, as recommended by industry leaders at EY. This involves creating cross-functional teams to continually assess AI’s impact on learning and well-being.

6. Invest in Sustainable Infrastructure: Prioritize renewable-powered cloud providers and perform continuous audits of energy and water consumption related to AI workloads.

For Policymakers:

The role of government is crucial in shaping a healthy AI ecosystem. Policymakers must work to create a global consensus on AI regulation, learning from successful international models while crafting domestic policies that support both innovation and responsible, human-centered use.

These steps are not about stifling innovation. They are about building the necessary foundation of trust and sustainability for AI’s successful and long-term integration into our society.

The EP View: Embracing AI with Eyes Wide Open

Artificial intelligence is neither the utopian solution some have promised nor the existential threat others have feared. It is a powerful tool—and like any tool, its ultimate value will be determined by the wisdom and foresight of those who wield it. The magic is compelling, but we can no longer afford to be mystified by the illusion. True literacy means looking behind the curtain and understanding the machinery and the costs.

The future of learning and work will undoubtedly be AI-enabled. It is our collective responsibility to ensure that this future is also human-centered, equitable, and environmentally conscious. To do so, we must move forward with our eyes wide open, ready to ask the hard questions and build a world where technological progress serves human values and planetary health.

The Sciences

Researchers crack greener way to mine lithium, cobalt and nickel from dead batteries

A breakthrough recycling method developed at Monash University in Australia can recover over 95% of critical metals from spent lithium-ion batteries—without extreme heat or toxic chemicals—offering a major boost to clean energy and circular economy goals.

Researchers at Monash University, based in Melbourne, Australia, have developed a breakthrough, environmentally friendly method to recover high-purity nickel, cobalt, manganese and lithium from spent lithium-ion batteries, offering a safer alternative to conventional recycling processes.

The new approach uses a mild and sustainable solvent, avoiding the high temperatures and hazardous chemicals typically associated with battery recycling. The innovation comes at a critical time, as an estimated 500,000 tonnes of spent lithium-ion batteries have already accumulated globally. Despite their growing volume, recycling rates remain low, with only around 10 per cent of spent batteries fully recycled in countries such as Australia.

Most discarded batteries end up in landfills, where toxic substances can seep into soil and groundwater, gradually entering the food chain and posing long-term health and environmental risks. This is particularly concerning given that spent lithium-ion batteries are rich secondary resources, containing strategic metals including lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, aluminium and graphite.

Existing recovery methods often extract only a limited range of elements and rely on energy-intensive or chemically aggressive processes. The Monash team’s solution addresses these limitations by combining a novel deep eutectic solvent (DES) with an integrated chemical and electrochemical leaching process.

Dr Parama Banerjee, principal supervisor and project lead from the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, said the new method achieves more than 95 per cent recovery of nickel, cobalt, manganese and lithium, even from industrial-grade “black mass” that contains mixed battery chemistries and common impurities.

“This is the first report of selective recovery of high-purity Ni, Co, Mn, and Li from spent battery waste using a mild solvent,” Dr Banerjee said.

“Our process not only provides a safer, greener alternative for recycling lithium-ion batteries but also opens pathways to recover valuable metals from other electronic wastes and mine tailings.”

Parisa Biniaz, PhD student and co-author of the study, said the breakthrough represents a significant step towards a circular economy for critical metals while reducing the environmental footprint of battery disposal.

“Our integrated process allows high selectivity and recovery even from complex, mixed battery black mass. The research demonstrates a promising approach for industrial-scale recycling, recovering critical metals efficiently while minimising environmental harm,” Biniaz said.

The researchers say the method could play a key role in supporting sustainable energy transitions by securing critical mineral supplies while cutting down on environmental damage from waste batteries.

Technology

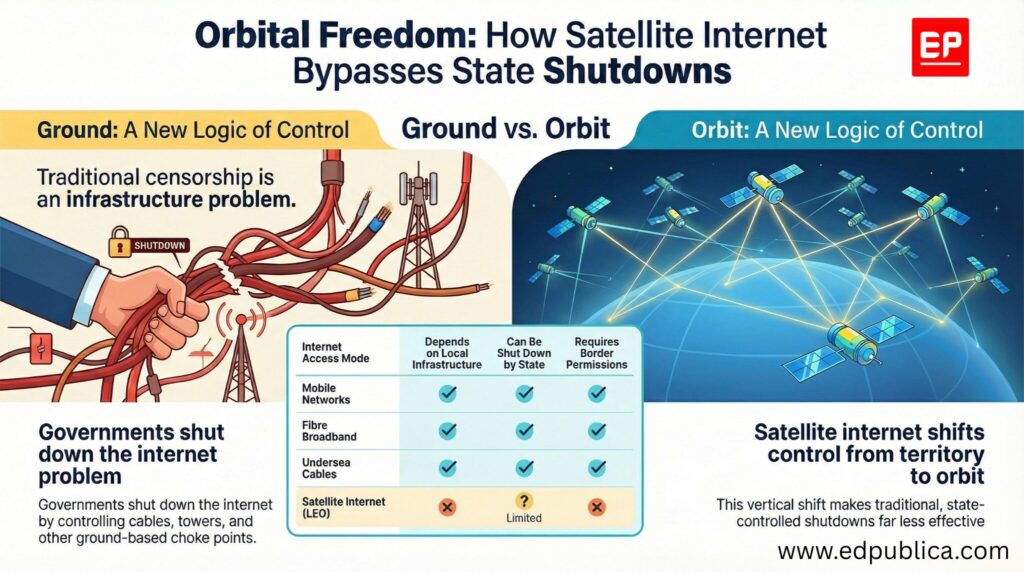

From Tehran Rooftops To Orbit: How Elon Musk Is Reshaping Who Controls The Internet

How Starlink turned the sky into a battleground for digital power — and why one private network now challenges the sovereignty of states

On a rooftop in northern Tehran, long after midnight, a young engineering student adjusts a flat white dish toward the sky. The city around him is digitally dark—mobile data throttled, social media blocked, foreign websites unreachable. Yet inside his apartment, a laptop screen glows with Telegram messages, BBC livestreams, and uncensored access to the outside world.

Scenes like this have appeared repeatedly in footage from Iran’s unrest broadcast by international news channels.

But there’s a catch. The connection does not travel through Iranian cables or telecom towers. It comes from space.

Above him, hundreds of kilometres overhead, a small cluster of satellites belonging to Elon Musk’s Starlink network relays his data through the vacuum of orbit, bypassing the state entirely.

For governments built on control of information, this is no longer a technical inconvenience. It is a political nightmare. The image is quietly extraordinary. Not because of the technology — that story is already familiar — but because of what it represents: a private satellite network, owned by a US billionaire, now functioning as a parallel communications system inside a sovereign state that has deliberately tried to shut its citizens offline.

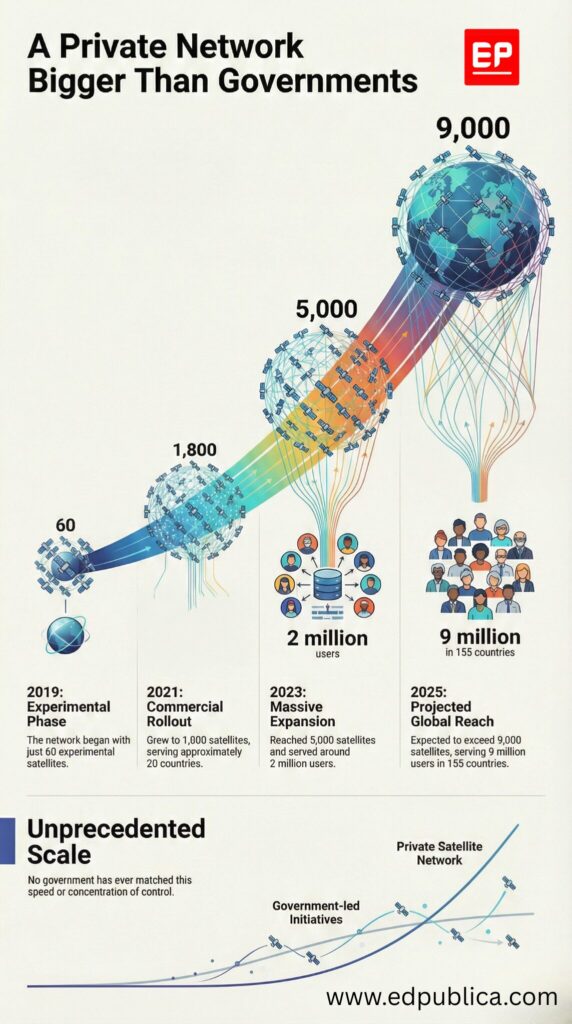

The Rise of an Unstoppable Network

Starlink, operated by Musk’s aerospace company SpaceX, has quietly become the most ambitious communications infrastructure ever built by a private individual.

As of late 2025, more than 9,000 Starlink satellites orbit Earth in low Earth orbit (LEO) (SpaceX / industry trackers, 2025). According to a report in Business Insider, the network serves over 9 million active users globally, and Starlink now operates in more than 155 countries and territories (Starlink coverage data, 2025).

It is the largest satellite constellation in human history, dwarfing every government system combined.

This is not merely a technology story. It is a power story.

Unlike traditional internet infrastructure — fibre cables, mobile towers, undersea routes — Starlink’s backbone exists in space. It does not cross borders. It does not require landing rights in the conventional sense. And, increasingly, it does not ask permission.

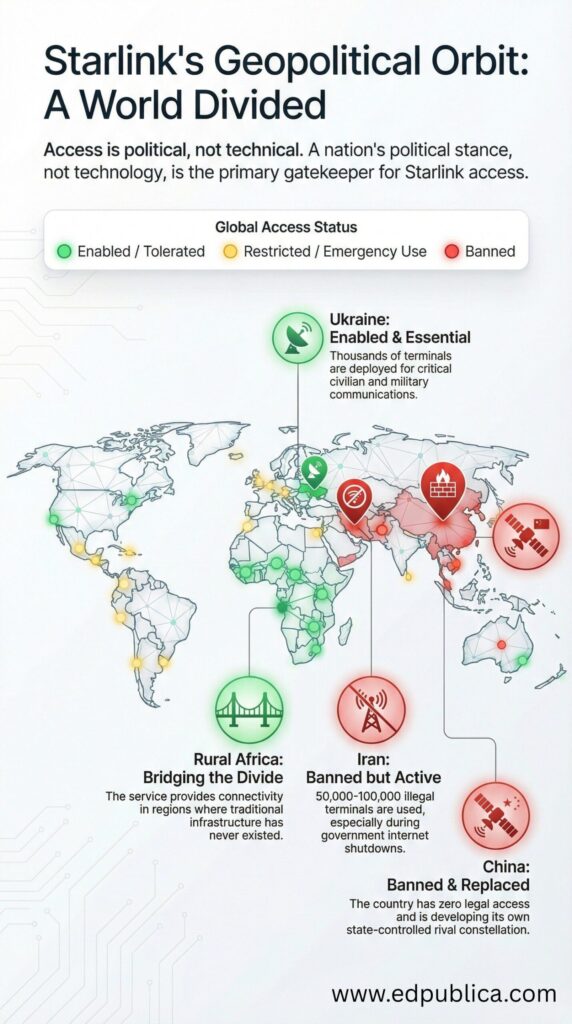

Iran: When the Sky Replaced the State

During successive waves of anti-government protests in Iran, authorities imposed sweeping internet shutdowns: mobile networks crippled, platforms blocked, bandwidth throttled to near zero. These tactics, used repeatedly since 2019, were designed to isolate protesters from each other and from the outside world.

They did not fully anticipate space-based internet.

By late 2024 and 2025, Starlink terminals had begun appearing clandestinely across Iranian cities, smuggled through borders or carried in by diaspora networks. Possession is illegal. Penalties are severe. Yet the demand has grown.

Because the network operates without local infrastructure, users can communicate with foreign media, upload protest footage in real time, coordinate securely beyond state surveillance, and maintain access even during nationwide blackouts.

The numbers are necessarily imprecise, but multiple independent estimates provide a sense of scale. Analysts at BNE IntelliNews estimated over 30,000 active Starlink users inside Iran by 2025.

Iranian activist networks suggest the number of physical terminals may be between 50,000 and 100,000, many shared across neighbourhoods. Earlier acknowledgements from Elon Musk confirmed that SpaceX had activated service coverage over Iran despite the lack of formal licensing.

This is what alarms governments most: the state no longer controls the kill switch.

Ukraine: When One Man Could Switch It Off

The power — and danger — of this new infrastructure became even clearer in Ukraine.

After Russia’s 2022 invasion, Starlink terminals were shipped in by the thousands to keep Ukrainian communications alive. Hospitals, emergency services, journalists, and frontline military units all relied on it. For a time, Starlink was celebrated as a technological shield for democracy.

Then came the uncomfortable reality.

Investigative reporting later revealed that Elon Musk personally intervened in decisions about where Starlink would and would not operate. In at least one documented case, coverage was restricted near Crimea, reportedly to prevent Ukrainian drone operations against Russian naval assets.

The implications were stark: A private individual, accountable to no electorate, had the power to influence the operational battlefield of a sovereign war. Governments noticed.

Digital Sovereignty in the Age of Orbit

For decades, states have understood sovereignty to include control of national telecom infrastructure, regulation of internet providers, the legal authority to impose shutdowns, the power to filter, censor, and surveil.

Starlink disrupts all of it.

Because, the satellites are in space, outside national jurisdiction. Access can be activated remotely by SpaceX, and the terminals can be smuggled like USB devices. Traffic can bypass domestic data laws entirely.

In effect, Starlink represents a parallel internet — one that states cannot fully regulate, inspect, or disable without extraordinary countermeasures such as satellite jamming or physical raids.

Authoritarian regimes view this as foreign interference. Democratic governments increasingly see it as a strategic vulnerability. Either way, the monopoly problem is the same: A single corporate network, controlled by one individual, increasingly functions as critical global infrastructure.

How the Technology Actually Works

The power of Starlink lies in its architecture. Traditional internet depends on fibre-optic cables across cities and oceans, local internet exchanges, mobile towers and ground stations, and centralised chokepoints.

Starlink bypasses most of this. Instead, it uses thousands of LEO satellites orbiting at ~550 km altitude, user terminals (“dishes”) that automatically track satellites overhead, inter-satellite laser links, allowing data to travel from satellite to satellite in space, and a limited number of ground gateways connecting the system to the wider internet.

This design creates resilience: No single tower to shut down, no local ISP to regulate, and no fibre line to cut.

For protesters, journalists, and dissidents, this is transformative. For governments, it is destabilising.

A Private Citizen vs the Rules of the Internet

The global internet was built around multistakeholder governance: National regulators, international bodies like the ITU, treaties governing spectrum use, and complex norms around cross-border infrastructure.

Starlink bypasses much of this through sheer technical dominance, and it has become a company that: owns the rockets, owns the satellites, owns the terminals, controls activation, controls pricing, controls coverage zones… effectively controls a layer of global communication.

This is why policymakers now speak openly of “digital sovereignty at risk”. It is no longer only China’s Great Firewall or Iran’s censorship model under scrutiny. It is the idea that global connectivity itself might be increasingly privatised, personalised, and politically unpredictable.

The Unanswered Question

Starlink undeniably delivers real benefits, it offers connectivity in disaster zones, internet access in rural Africa, emergency communications in war, educational access where infrastructure never existed.

But it also raises an uncomfortable, unresolved question: Should any individual — however visionary, however innovative — hold this much power over who gets access to the global flow of information?

Today, a protester in Tehran can speak to the world because Elon Musk chooses to allow it.

Tomorrow, that access could disappear just as easily — with a policy change, a commercial decision, or a geopolitical calculation.The sky has become infrastructure. Infrastructure has become power. And power, increasingly, belongs not to states — but to a handful of corporations.

There is another layer to this power calculus — and it is economic. While Starlink has been quietly enabled over countries such as Iran without formal approval, China remains a conspicuous exception. The reason is less technical than commercial. Elon Musk’s wider business empire, particularly Tesla, is deeply entangled with China’s economy. Shanghai hosts Tesla’s largest manufacturing facility in the world, responsible for more than half of the company’s global vehicle output, and Chinese consumers form one of Tesla’s most critical markets.

Chinese authorities, in turn, have made clear their hostility to uncontrolled foreign satellite internet, viewing it as a threat to state censorship and information control. Beijing has banned Starlink terminals, restricted their military use, and invested heavily in its own rival satellite constellation. For Musk, activating Starlink over China would almost certainly provoke regulatory retaliation that could jeopardise Tesla’s operations, supply chains, and market access. The result is an uncomfortable contradiction: the same technology framed as a tool of freedom in Iran or Ukraine is conspicuously absent over China — a reminder that even a supposedly borderless internet still bends to the gravitational pull of corporate interests and geopolitical power.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth4 months ago

Earth4 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science5 months ago

Women In Science5 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet