Space & Physics

Chandrayaan-3: The moon may have had a fiery past

A magma ocean might’ve wrapped the ancient moon, suggests findings from India’s robotic lunar mission, Chandrayaan-3.

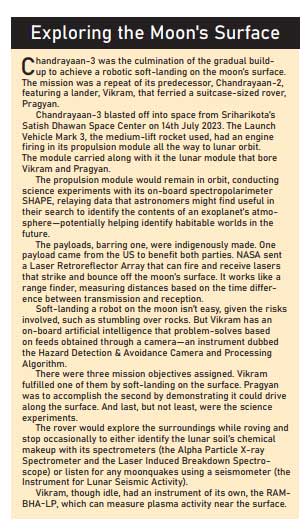

On 23rd August last year, India’s Chandrayaan-3 made history being the first to soft-land on the moon’s south polar region. The landing marked the end of the high-octane phase of the mission. But its next phase was a slow-burner.

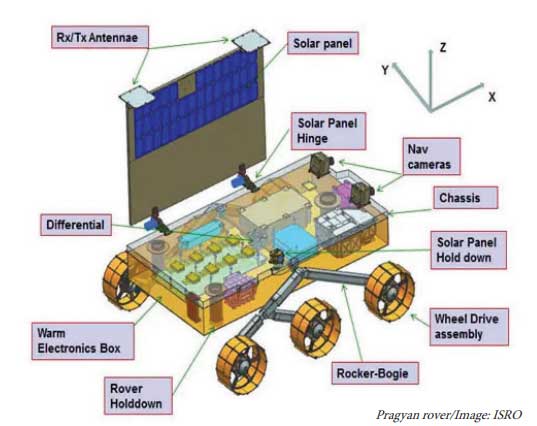

Pragyan, the suitcase-sized rover, that hitched a ride to the moon aboard the lander, Vikram, rolled off a ramp onto the lunar surface. It traversed along the dusty lunar surface slowly, at a pace even a snail could beat. Handlers at the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) didn’t want the suitcase-sized rover to risk stumbling over a rock or near a ridge, and jeopardize the mission.

The whitish spots are material excavated from the moon’s interior.

Nevertheless, the rover had a busy schedule to stick to. It was to probe the lunar soil, and relay that scientific data back to earth. Pragyan covered 100 meters in two weeks, before it stopped to take a nap ahead of a long lunar night. At the time, the rover’s battery pack was fully charged, thanks to the on-board solar panels soaking up sunlight during the day.

But lunar weather is harsh, especially at the south pole, where Pragyan napped, temperatures can reach as low as -250 degrees centigrade during the night. Added to that, a lunar night lasts two weeks. ISRO deemed Pragyan had only a 1% chance to survive.

Later, the expected happened, when the rover went unresponsive to ISRO’s pings to wake up.

But ISRO said the rover achieved what it was tasked to do. It relayed data all along for two weeks, examining soil from some 23 locations around the mission’s landing point, Statio Shiv Shakti. As months passed by, a slew of discoveries were made. Sulphur was discovered at the south pole, early on while the mission was ongoing. And only a few months ago, Pragyan found evidence of past weathering activity at the south pole.

But since August this year, research teams from ISRO and the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad, India, reported Pragyan’s most important findings yet – one of which sheds light onto the moon’s origins.

Chandrayaan-3’s Vikram lander, seen from the Pragyan rover’s camera

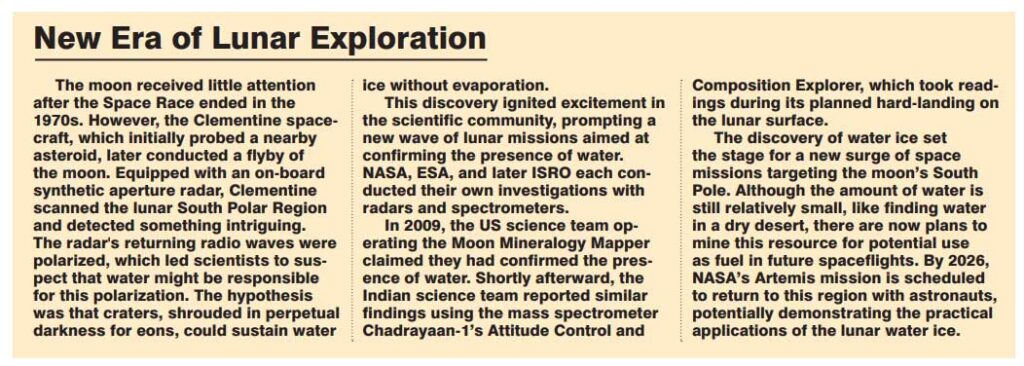

Moon and the Early Earth

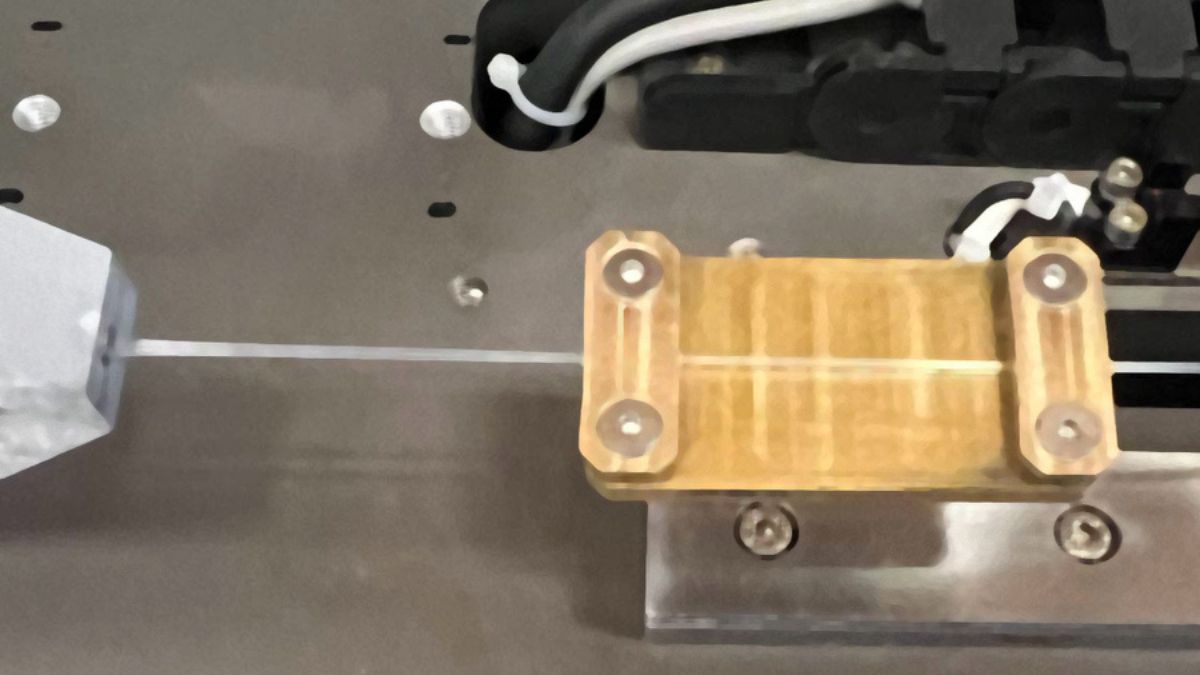

Chandrayaan-3 had carried a radioactive passenger to the moon’s surface – curium-244.

The radioactive curium helps lase the surface: firing alpha particles (which are helium nuclei) at the dusty terrain. Some of these alpha particles bounce off the dust, whereas others evict electrons from the lunar soil, thereby producing x-ray emissions. Keeping watch is the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) on-board the Pragyan rover. In August, PRL scientists published findings in the journal, Nature, based on APXS data, reporting discovery of ferroan anorthosite.

It wasn’t the first ever detection per se of ferroan anorthosite. In fact, Apollo 11 had brought back anorthosite rocks to earth, where they were identified as such. That was in 1969, and Apollo sampled them from the equator. Successive missions by the Soviet Union and most recently China affirmed likewise from mid-latitude – equatorial regions as well. But Pragyan’s detection of the rock type was the first ever from the polar region.

The Pragyan rover’s payload.

Anorthosites are common on earth. In fact, just a year after the Apollo 11 sampled the rock, scientists had evidence of the earth and the moon’s entangled history. The authors noted the similar composition between these rocks, that are geographically widespread. Furthermore, ferroan anorthosite is an igneous rock that forms on earth when hot lava produced in volcanic eruptions cools down.

And scientists had piled up evidence in support of a similar process that underwent on the moon. The anorthosite rocks on the moon are old, in fact, more than 4 billion years ago – a figure close to the earth’s inception with rest of the solar system – around 4.5 billion years. Scientific consensus has been that the moon was formed from remnants of a collision between the early earth and a rogue Mars-sized planetary body.

But the collision energy would have yielded a moon that was molten. A lava blanketing the surface – aka a global magma ocean. As this ocean cooled, minerals amongst which is plagioclase (a class of feldspar) crystallized and formed the anorthosite rocks on the moon. It’s commonly called the lunar magma ocean hypothesis.

When Pragyan treaded over the dusty lunar terrain, it didn’t register the anorthosite as a physical rock per se. Instead, it observed remnants of the rock, as fine powder.

Meteorites beat down rocks to fine powder, as they slam into the moon from space with regular impunity. On earth, the ground is saved by the presence of an atmosphere. But the moon virtually has no atmosphere. Nor does it have water to wear down the rocks. The surface is extremely hot during the lunar day – in fact, when Chandrayaan-3 landed on the moon, the surface temperature was some 50 degrees centigrade. Just a few months ago, Pragyan revealed possible signs of rock degradation from the rims of a crater.

Moon dust opens doors to the past

The fact the moon doesn’t (and can’t) sustain an atmosphere helps it make an attractive destination to learn more about our planet and the satellite’s shared origins. There’s no chemistry to remove traces of the moon’s early evolution from the lunar dust. As such, the dust opens doors to the past.

Space explorations missions soft-landing on the surface study this dust – or sample and shuttle them to earth for scientists to study them in detail.

In fact, Pragyan revealed a crater that’s amongst the oldest ever discovered on the moon. The findings were published in the journal, Icarus, in September. Hidden in plain sight, the rover’s navigation camera, NavCam, spotted subtle stretch marks on the surface, that were confirmed later with the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter (which has been orbiting the moon since 2019). In fact, this crater was found buried under nearby craters, most notably the South Pole-Aitkin basin located 350 km away. The basin is the largest impact crater in the entire solar system (some 2,500 km wide and 8 km deep) touted to have formed millions of years ago.

And this became subject to an earlier paper that PRL scientists authored, and was published in August. Pragyan identified material thought to have emerged from the moon’s interior. The APXS instrument picked up unusually high magnesium content in the vicinity. The authors speculate the meteorite that created the basin probably dug up magnesium from deep inside the moon’s upper mantle, and spewed them into Pragyan’s vicinity.

But some experts believe in an alternate explanation. They believe the magnesium might have come from surface rocks in the vicinity, and not from the upper mantle. In fact, the authors acknowledged this amongst other possible alternatives. Nonetheless, the Chandrayaan-3’s findings doesn’t dispute the lunar magma ocean hypothesis either, if not backing it outright. Saying that, the theory lives on to fight another day.

Space & Physics

Researchers Develop Stretchable Material That Can Instantly Switch How It Conducts Heat

MIT engineers have developed a stretchable material heat conduction system that can rapidly switch how heat flows, enabling adaptive cooling applications.

Stretchable material heat conduction has taken a major leap forward as engineers at MIT have developed a polymer that can rapidly and reversibly switch how it conducts heat simply by being stretched. The discovery opens new possibilities for adaptive cooling technologies in clothing, electronics, and building infrastructure.

Engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed a new polymer material that can rapidly and reversibly switch how it conducts heat—simply by being stretched.

The research shows that a commonly used soft polymer, known as an olefin block copolymer (OBC), can more than double its thermal conductivity when stretched, shifting from heat-handling behaviour similar to plastic to levels closer to marble. When the material relaxes back to its original form, its heat-conducting ability drops again, returning to its plastic-like state.

The transition happens extremely fast—within just 0.22 seconds—making it the fastest thermal switching ever observed in a material, according to the researchers.

The findings open up possibilities for adaptive materials that respond to temperature changes in real time, with potential applications ranging from cooling fabrics and wearable technology to electronics, buildings, and infrastructure.

The research team initially began studying the material while searching for more sustainable alternatives to spandex, a petroleum-based elastic fabric that is difficult to recycle. During mechanical testing, the researchers noticed unexpected changes in how the polymer handled heat as it was stretched and released.

A new direction for adaptive materials

“We need materials that are inexpensive, widely available, and able to adapt quickly to changing environmental temperatures,” said Svetlana Boriskina, principal research scientist in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, in a media statement. She explained that the discovery of rapid thermal switching in this polymer creates new opportunities to design materials that actively manage heat rather than passively resisting it.

The research team initially began studying the material while searching for more sustainable alternatives to spandex, a petroleum-based elastic fabric that is difficult to recycle. During mechanical testing, the researchers noticed unexpected changes in how the polymer handled heat as it was stretched and released.

“What caught our attention was that the material’s thermal conductivity increased when stretched and decreased again when relaxed, even after thousands of cycles,” said Duo Xu, a co-author of the study, in a media statement. He added that the effect was fully reversible and occurred while the material remained largely amorphous, which contradicted existing assumptions in polymer science.

The discovery demonstrates how stretchable material heat conduction can be actively controlled in real time, allowing materials to respond dynamically to temperature changes.

How stretching unlocks heat flow

At the microscopic level, most polymers consist of tangled chains of carbon atoms that block heat flow. The MIT team found that stretching the olefin block copolymer temporarily straightens these tangled chains and aligns small crystalline regions, creating clearer pathways for heat to travel through the material.

“This gives the material the ability to toggle its heat conduction thousands of times without degrading

Unlike earlier work on polyethylene—where similar alignment permanently increased thermal conductivity—the new material does not crystallise under strain. Instead, its internal structure switches back and forth between straightened and tangled states, allowing repeated and reversible thermal switching.

“This gives the material the ability to toggle its heat conduction thousands of times without degrading,” Xu said.

From smart clothing to cooler electronics

The researchers say the material could be engineered into fibres for clothing that normally retain heat but instantly dissipate excess warmth when stretched. Similar concepts could be applied to electronics, laptops, and buildings, where materials could respond dynamically to overheating without external cooling systems.

“The difference in heat dissipation is similar to the tactile difference between touching plastic and touching marble,” Boriskina said in a media statement, highlighting how noticeable the effect can be.

The team is now working on optimising the polymer’s internal structure and exploring related materials that could produce even larger thermal shifts.

“If we can further enhance this effect, the industrial and societal impact could be substantial,” Boriskina said.

Researchers say advances in stretchable material heat conduction could significantly influence future designs of smart textiles, electronics cooling, and energy-efficient buildings.

The study has been published in the journal Advanced Materials. The authors include researchers from MIT and the Southern University of Science and Technology in China.

Researchers say advances in stretchable material heat conduction could significantly influence future designs of smart textiles, electronics cooling, and energy-efficient buildings.

Space & Physics

Physicists Capture ‘Wakes’ Left by Quarks in the Universe’s First Liquid

Scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider have observed, for the first time, fluid-like wakes created by quarks moving through quark–gluon plasma, offering direct evidence that the universe’s earliest matter behaved like a liquid rather than a cloud of free particles.

Physicists working at the CERN(The European Organization for Nuclear Research) have reported the first direct experimental evidence that quark–gluon plasma—the primordial matter that filled the universe moments after the Big Bang—behaves like a true liquid.

Using heavy-ion collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, researchers recreated the extreme conditions of the early universe and observed that quarks moving through this plasma generate wake-like patterns, similar to ripples trailing a duck across water.

The study, led by physicists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, shows that the quark–gluon plasma responds collectively, flowing and splashing rather than scattering randomly.

“It has been a long debate in our field, on whether the plasma should respond to a quark,” said Yen-Jie Lee in a media statement. “Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark, and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup.”

Quark–gluon plasma is believed to be the first liquid to have existed in the universe and the hottest ever observed, reaching temperatures of several trillion degrees Celsius. It is also considered a near-perfect liquid, flowing with almost no resistance.

To isolate the wake produced by a single quark, the team developed a new experimental technique. Instead of tracking pairs of quarks and antiquarks—whose effects can overlap—they identified rare collision events that produced a single quark traveling in the opposite direction of a Z boson. Because a Z boson interacts weakly with its surroundings, it acts as a clean marker, allowing scientists to attribute any observed plasma ripples solely to the quark.

“We have figured out a new technique that allows us to see the effects of a single quark in the QGP, through a different pair of particles,” Lee said.

Analysing data from around 13 billion heavy-ion collisions, the researchers identified roughly 2,000 Z-boson events. In these cases, they consistently observed fluid-like swirls in the plasma opposite to the Z boson’s direction—clear signatures of quark-induced wakes.

The results align with theoretical predictions made by MIT physicist Krishna Rajagopal, whose hybrid model suggested that quarks should drag plasma along as they move through it.

“This is something that many of us have argued must be there for a good many years, and that many experiments have looked for,” Rajagopal said.

“We’ve gained the first direct evidence that the quark indeed drags more plasma with it as it travels,” Lee added. “This will enable us to study the properties and behavior of this exotic fluid in unprecedented detail.”

The research was carried out by members of the CMS Collaboration using the Compact Muon Solenoid detector at CERN. The open-access study has been published in the journal Physics Letters B.

Space & Physics

Why Jupiter Has Eight Polar Storms — and Saturn Only One: MIT Study Offers New Clues

Two giant planets, made of the same elements, display radically different storms at their poles. New research from MIT now suggests that the key to this cosmic mystery lies not in the skies, but deep inside Jupiter and Saturn themselves.

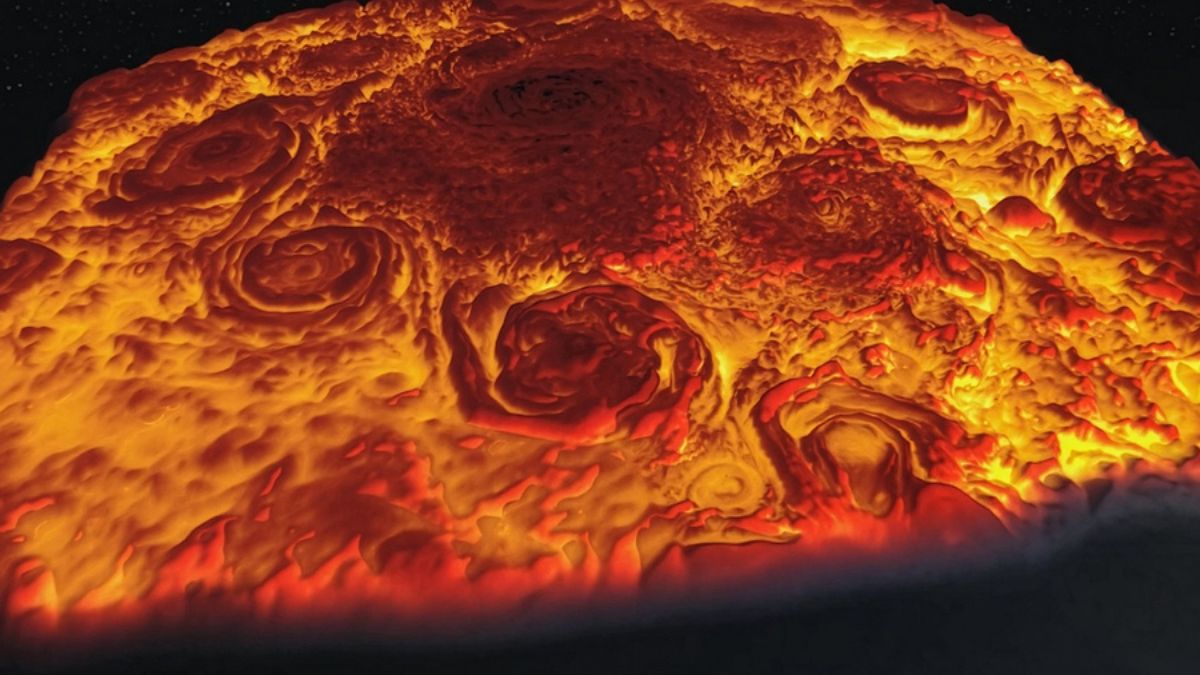

For decades, spacecraft images of Jupiter and Saturn have puzzled planetary scientists. Despite being similar in size and composition, the two gas giants display dramatically different weather systems at their poles. Jupiter hosts a striking formation: a central polar vortex encircled by eight massive storms, resembling a rotating crown. Saturn, by contrast, is capped by a single enormous cyclone, shaped like a near-perfect hexagon.

Now, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology believe they have identified a key reason behind this cosmic contrast — and the answer may lie deep beneath the planets’ cloud tops.

In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the MIT team suggests that the structure of a planet’s interior — specifically, how “soft” or “hard” the base of a vortex is — determines whether polar storms merge into one giant system or remain as multiple smaller vortices.

“Our study shows that, depending on the interior properties and the softness of the bottom of the vortex, this will influence the kind of fluid pattern you observe at the surface,” says study author Wanying Kang, assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) in a media release issued by the institute. “I don’t think anyone’s made this connection between the surface fluid pattern and the interior properties of these planets. One possible scenario could be that Saturn has a harder bottom than Jupiter.”

A long-standing planetary mystery

The contrast has been visible for years thanks to two landmark NASA missions. The Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, revealed a dramatic polar arrangement of swirling storms, each roughly 3,000 miles wide — nearly half the diameter of Earth. Cassini, which orbited Saturn for 13 years before its mission ended in 2017, documented the planet’s iconic hexagonal polar vortex, stretching nearly 18,000 miles across.

“People have spent a lot of time deciphering the differences between Jupiter and Saturn,” says Jiaru Shi, the study’s first author and an MIT graduate student. “The planets are about the same size and are both made mostly of hydrogen and helium. It’s unclear why their polar vortices are so different.”

Simulating storms on gas giants

To tackle the question, the researchers turned to computer simulations. They created a two-dimensional model of atmospheric flow designed to mimic how storms might evolve on a rapidly rotating gas giant.

While real planetary vortices are three-dimensional, the team argued that Jupiter’s and Saturn’s fast spin simplifies the physics. “In a fast-rotating system, fluid motion tends to be uniform along the rotating axis,” Kang explains. “So, we were motivated by this idea that we can reduce a 3D dynamical problem to a 2D problem because the fluid pattern does not change in 3D. This makes the problem hundreds of times faster and cheaper to simulate and study.”

The model allowed the scientists to test thousands of possible planetary conditions, varying factors such as rotation rate, internal heating, planet size and — crucially — the density of material beneath the vortices. Each simulation began with random chaotic motion and tracked how storms evolved over time.

The outcomes consistently fell into two categories: either the system developed one dominant polar vortex, like Saturn, or several coexisting vortices, like Jupiter.

The decisive factor turned out to be how much a vortex could grow before being constrained by the properties of the layers beneath it.

When the lower layers were made of softer, lighter material, individual vortices could not expand indefinitely. Instead, they stabilized at smaller sizes, allowing multiple storms to coexist at the pole. This matches what scientists observe on Jupiter.

But when the simulated vortex base was denser and more rigid, vortices were able to grow larger and eventually merge. The end result was a single, planet-scale storm — remarkably similar to Saturn’s massive polar cyclone.

“This equation has been used in many contexts, including to model midlatitude cyclones on Earth,” Kang says. “We adapted the equation to the polar regions of Jupiter and Saturn.”

The findings suggest that Saturn’s interior may contain heavier elements or more condensed material than Jupiter’s, giving its atmospheric vortices a firmer foundation to build upon.

“What we see from the surface, the fluid pattern on Jupiter and Saturn, may tell us something about the interior, like how soft the bottom is,” Shi says. “And that is important because maybe beneath Saturn’s surface, the interior is more metal-enriched and has more condensable material which allows it to provide stronger stratification than Jupiter. This would add to our understanding of these gas giants.”

Reading the interiors from the skies

Planetary scientists have long struggled to infer the internal structures of gas giants, where pressures and temperatures are far beyond what can be reproduced in laboratories. This new work offers a rare bridge between visible atmospheric patterns and hidden planetary composition.

Beyond explaining two of the Solar System’s most visually striking storms, the research could shape how scientists interpret observations of distant exoplanets as well — worlds where atmospheric patterns might be the only clues to what lies within.

For now, Jupiter’s swirling crown of storms and Saturn’s solitary hexagon may be doing more than decorating the poles of two distant giants. They may be quietly revealing the deep, unseen architecture of the planets themselves.

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoThe Ten-Rupee Doctor Who Sparked a Health Revolution in Kerala’s Tribal Highlands

-

COP304 months ago

COP304 months agoBrazil Cuts Emissions by 17% in 2024—Biggest Drop in 16 Years, Yet Paris Target Out of Reach

-

Earth3 months ago

Earth3 months agoData Becomes the New Oil: IEA Says AI Boom Driving Global Power Demand

-

COP303 months ago

COP303 months agoCorporate Capture: Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP30 Hit Record High, Outnumbering Delegates from Climate-Vulnerable Nations

-

Society2 months ago

Society2 months agoFrom Qubits to Folk Puppetry: India’s Biggest Quantum Science Communication Conclave Wraps Up in Ahmedabad

-

Space & Physics2 months ago

Space & Physics2 months agoIndian Physicists Win 2025 ICTP Prize for Breakthroughs in Quantum Many-Body Physics

-

Women In Science4 months ago

Women In Science4 months agoThe Data Don’t Lie: Women Are Still Missing from Science — But Why?

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoAir Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet