Health

Scientist urges need for an Indian-specific blood parameter reference range

In India, standard blood parameter reference ranges aren’t representative of the local population; but based on conclusions derived from population studies in the West.

Prof. Ullas Kolthur-Seetharam, a leading Indian scientist in metabolism and aging, has urged for the re-optimization of standard blood parameter reference ranges to better suit Indian populations, highlighting that current values are based on Western populations and may not account for India-specific factors.

Speaking at the National Technology Day (NTD) 2025 lecture at the Biotechnology Research and Innovation Council-Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology (BRIC-R caballoGCB), Kerala, India, Prof. Kolthur-Seetharam emphasized the need for tailored diagnostic benchmarks to improve the accuracy of diagnosing metabolic disorders like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in India.

“Genetic, dietary, and environmental differences can significantly alter biomarkers,” said Prof. Kolthur-Seetharam, Director of the Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (BRIC-CDFD), Hyderabad, India. He noted that emerging research reveals how dietary patterns influence health through mitochondrial function and epigenetic regulation, necessitating India-specific reference ranges.

Currently on deputation from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Mumbai, Prof. Kolthur-Seetharam has made significant contributions to understanding the interplay of mitochondrial function, epigenetics, and nutrition in shaping health and longevity. He also founded The Advanced Research Unit on Metabolism, Development & Aging (ARUMDA) at TIFR, a pioneering initiative tackling India’s challenges with malnutrition, non-communicable diseases, and aging through interdisciplinary research.

Health

Air Pollution Claimed 1.7 Million Indian Lives and 9.5% of GDP, Finds The Lancet

In 2022 alone, fine particulate pollution — PM2.5 — killed an estimated 1.7 million people in India, according to the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change 2025.

In 2022 alone, fine particulate pollution — PM2.5 — killed an estimated 1.7 million people in India, according to the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change 2025.

The same toxic particles that fill Delhi’s winter air and blanket cities from Kanpur to Kolkata also caused economic losses equivalent to 9.5% of India’s GDP, revealing that air pollution is not just a public health emergency, but a national economic crisis hiding in plain sight.

A Crisis Woven into Everyday Life

India’s worsening air quality is no longer a seasonal problem. According to The Lancet Countdown, over a third of Indians were exposed to PM2.5 levels exceeding World Health Organization (WHO) limits for more than 10 months of the year.

Rising temperatures, urban sprawl, and fossil fuel combustion — from coal-fired power plants to vehicle emissions — have created a deadly feedback loop that is choking the country’s lungs and its economy.

“Air pollution in India is a silent pandemic. It’s not only shortening lives, but undermining productivity, healthcare systems, and economic growth,” said Dr. Marina Romanello, Executive Director of The Lancet Countdown, in the report’s global launch statement.

The Health Toll: From Newborns to the Elderly

The Lancet Countdown 2025 estimates that the global death toll from air pollution reached 8.3 million in 2022, with India accounting for over one-fifth of those fatalities.

PM2.5 — particles less than 2.5 microns in diameter — penetrate deep into lungs and bloodstreams, causing or worsening heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and respiratory illness.

In India, the burden falls disproportionately on the poorest households, who are more likely to live near highways, coal plants, or industrial clusters and have limited access to healthcare.

Children and elderly people are the most vulnerable: the report highlights that exposure to dirty air increases the risk of low birth weight, premature births, and chronic illness later in life.

Counting the Cost: 9.5% of GDP Lost

The Lancet Countdown’s economic assessment, based on lost labour productivity, healthcare costs, and premature deaths, found that India lost 9.5% of its GDP in 2022 due to air pollution-related impacts.

That’s roughly equivalent to USD 300 billion — more than India’s entire annual education and health budgets combined.

Urban centres such as Delhi, Lucknow, and Patna rank among the most polluted in the world.

Air pollution is estimated to reduce life expectancy in northern India by up to 7 years, according to the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, underscoring how pervasive the damage has become.

“For a fast-growing economy like India, this is a double blow,” said Prof. Randeep Guleria, pulmonologist and former AIIMS director. “It burdens healthcare systems while reducing worker output — exactly the opposite of what a young nation needs.”

Climate and Air: The Same Enemy

The report connects India’s pollution crisis to its dependence on fossil fuels — especially coal — which remains the largest source of both CO₂ and PM2.5 emissions.

While government programmes such as the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) and electric mobility initiatives aim to reduce pollution, progress has been slow.

Many of the dirtiest thermal plants continue to operate without meeting emission standards, and vehicle emissions remain poorly regulated outside major cities.

“Air pollution is not a separate problem from climate change — it’s the same story told through different symptoms,” noted Dr. Romanello. “Every tonne of coal burned harms both lungs and the climate.”

This linkage is echoed in India’s own National Electricity Plan 2032, which outlines aggressive renewable targets, and in Ember’s 2025 analysis, which found that expanding coal capacity further would be economically irrational — a finding that strengthens the case for rapid decarbonisation.

Health as an Economic Argument

The Lancet Countdown reframes pollution not just as an environmental or health challenge, but as an economic imperative.

In India, labour losses due to heat and pollution exposure have grown by 42% since the early 2000s, with outdoor and informal workers suffering the most.

As heatwaves and smog increasingly overlap, lost work hours and rising healthcare costs could slow GDP growth by up to 1.8 percentage points annually by the mid-2030s if left unchecked.

Experts say cleaner power and transport sectors could deliver rapid wins:

- Phasing out coal and shifting to renewables can cut PM2.5 emissions by over 60% in key industrial zones.

- Expanding public transit and EV adoption can reduce vehicular PM2.5 by one-third in metropolitan regions.

- Strengthening NCAP’s monitoring and enforcement could save hundreds of thousands of lives each year.

From Policy to Breathable Air

Despite India’s national clean air mission and renewable push, enforcement and coordination remain major gaps.

The report calls for integrating air quality and climate policies, arguing that cutting fossil fuel use provides a “double dividend” — cleaner air and fewer greenhouse gases.

This integration has begun in limited form: several Indian states, including Gujarat and Maharashtra, have introduced emissions trading schemes for industrial pollutants.

But experts say scaling such initiatives nationally, alongside stricter vehicle standards and urban planning reforms, is critical for measurable results.

A Moment of Reckoning

The Lancet Countdown 2025 warns that air pollution and climate impacts are already reversing health gains made over decades.

India’s choice is no longer between growth and clean air — it’s about whether growth can continue at all under the weight of rising illness, lost labour, and degraded ecosystems.

“Air pollution is robbing India of its demographic dividend,” the report concludes. “Clean air is not a luxury; it’s a prerequisite for sustainable development.”

As the smog season begins once again in northern India, the data are unambiguous:

The invisible killer is now visible — and unaffordable.

References:

The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change 2025; The Lancet; Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC); Ember; CREA.

Health

Study Unveils Mucus Molecules That Block Salmonella and Prevent Diarrhea

A new MIT-led study reveals how key mucus molecules naturally shield the gut from dangerous bacteria like Salmonella

A new MIT-led study reveals how key mucus molecules naturally shield the gut from dangerous bacteria like Salmonella. The breakthrough opens new pathways for affordable, preventative treatments for travelers and soldiers at risk of infection.

Researchers at MIT have discovered new powerful ways the body guards itself from dangerous bacteria: by deploying mucins, special molecules in mucus that neutralize microbes and stop infection before it starts. The team identified mucins—especially MUC2 and MUC5AC—in the digestive tract that shut down the genetic machinery Salmonella uses to invade cells and cause diarrhea.

“By using and reformatting this motif from the natural innate immune system, we hope to develop strategies to preventing diarrhea before it even starts. This approach could provide a low-cost solution to a major global health challenge that costs billions annually in lost productivity, health care expenses, and human suffering,” said Katharina Ribbeck, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor of Biological Engineering at MIT, in a media statement.

In experiments, exposing Salmonella to the intestinal mucin MUC2 blocked the bacterial proteins that enable infection, turning off the critical regulator HilD. The study also found that a similar mucin from the stomach, MUC5AC, works the same way—and both molecules appear to protect against multiple foodborne germs triggered by similar genetic switches.

“We discovered that these mucins not only create a physical shield but also actively control whether pathogens can turn on genes needed for infection,” Ribbeck explained in the media statement.

Lead authors Kelsey Wheeler and Michaela Gold say synthetic versions of these mucins could soon be added to oral rehydration salts or chewable tablets, providing practical protection for troops, travelers, and people in high-risk areas. According to Wheeler, “Mucin mimics would particularly shine as preventatives, because that’s how the body evolved mucus — as part of this innate immune system to prevent infection,” she said.

Health

First Case of Rare and Deadly Fungus Identified in Sub-Saharan Africa

It is also the first time the rare and deadly fungal infection has been identified in an HIV-positive patient in the region

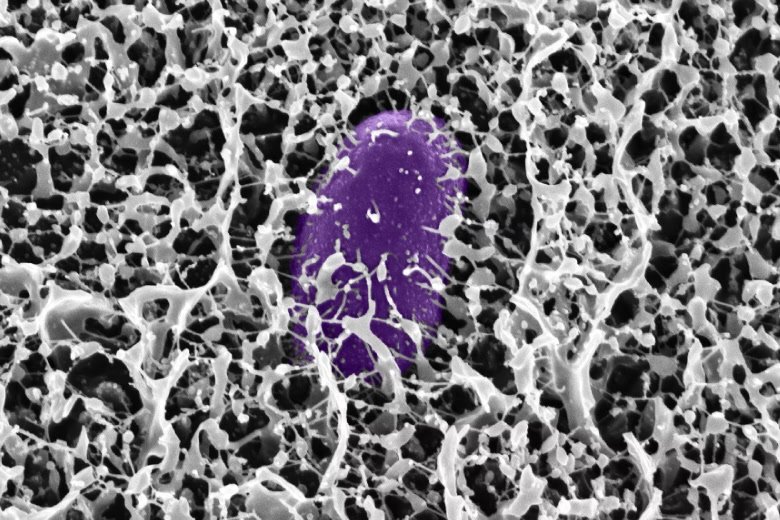

Doctors at the University of the Free State (UFS) and the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) at the Universitas Academic Hospital have confirmed the first recorded case of S. oblongispora mucormycosis in sub-Saharan Africa. It is also the first time the rare and deadly fungal infection has been identified in an HIV-positive patient in the region.

The case involved a 32-year-old man living with HIV who was admitted to Universitas Academic Hospital with severe swelling on the right side of his face. Despite being on antiretroviral therapy and treatment for hypertension, his condition worsened rapidly. Four days after admission, a CT scan and tissue biopsies were conducted. He died three days later, before a diagnosis could be confirmed.

Landmark discovery

Dr. Bonita van der Westhuizen, Senior Lecturer and Pathologist in the UFS Department of Medical Microbiology, described the discovery as a critical turning point for public health in the region.

“This discovery is significant because it highlights the presence of this fungal pathogen in a region where it may have been previously unrecognised or underreported. It now raises awareness about the diversity of fungal infections affecting immunocompromised populations and underscores the need for improved diagnostics, surveillance, and treatment strategies in the region,” she said in a media statement sent to EdPublica.

The case report, co-authored with Drs. Liska Budding and Christie Esterhuysen from the UFS/NHLS and Prof. Samantha Potgieter from the UFS Department of Internal Medicine, was published in Case Reports in Pathology last month.

Rapid and aggressive disease

Mucormycosis, caused by fungi from the order Mucorales, is known for its speed and severity. The infection can invade blood vessels, spread to vital organs, and resist the body’s immune defences.

“Mucorales fungi are known for their fast growth and ability to invade blood vessels. This allows the infection to spread quickly through the body, potentially reaching vital organs,” Dr. Van der Westhuizen explained in the statement. She added that external factors such as traumatic injuries or hospital-acquired infections can worsen the disease’s progression.

While mucormycosis usually strikes patients with underlying conditions like diabetes, cancer, or organ transplants, S. oblongispora has often been linked to infections in otherwise healthy individuals after traumatic inoculation. The lack of local data, however, means its prevalence in African populations remains unclear.

Diagnostic hurdles

In this case, invasive fungal infection was not initially suspected, and the patient did not receive antifungal medication or surgical treatment. The diagnosis was confirmed only after his death, highlighting the broader challenges of detecting fungal diseases in resource-limited settings.

“This is unfortunately the case with mould infections as most readily available diagnostic methods lack sensitivity and these pathogens take long to grow in the laboratory,” Dr. Van der Westhuizen said. “Fungal diagnostics is a specialised field that requires expertise. However, if clinicians are aware of these infections and they have an increased index of suspicion, appropriate therapy can be initiated even before the results are available.”

Experts warn that even with antifungal drugs and surgical removal of infected tissue, the window for treatment is narrow and survival rates remain low.

Building awareness and research

Dr. Van der Westhuizen is continuing her research on invasive mould infections as part of her PhD, focusing on fungal epidemiology and its impact on vulnerable groups such as HIV patients.

Her goal, she said in the media statement, is “to advance understanding and awareness of invasive mould infections, specifically S. oblongispora, in sub-Saharan Africa and among HIV patients. I aim to improve early diagnosis, treatment strategies, and clinical outcomes, as well as to highlight the importance of monitoring fungal infections in immunocompromised populations.”

She hopes the findings will spur more regional collaboration and investment in fungal diagnostics — an often overlooked but increasingly urgent frontier in infectious disease research.

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Know The Scientist6 months ago

Know The Scientist6 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoRemembering S.N. Bose, the underrated maestro in quantum physics

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoWhy the Arts Matter As Much As Science or Math

-

Earth5 months ago

Earth5 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”