Space & Physics

A New Milestone in Quantum Error Correction

This achievement moves quantum computing closer to becoming a transformative tool for science and technology

Quantum computing promises to revolutionize fields like cryptography, drug discovery, and optimization, but it faces a major hurdle: qubits, the fundamental units of quantum computers, are incredibly fragile. They are highly sensitive to external disturbances, making today’s quantum computers too error-prone for practical use. To overcome this, researchers have turned to quantum error correction, a technique that aims to convert many imperfect physical qubits into a smaller number of more reliable logical qubits.

In the 1990s, researchers developed the theoretical foundations for quantum error correction, showing that multiple physical qubits could be combined to create a single, more stable logical qubit. These logical qubits would then perform calculations, essentially turning a system of faulty components into a functional quantum computer. Michael Newman, a researcher at Google Quantum AI, highlights that this approach is the only viable path toward building large-scale quantum computers.

However, the process of quantum error correction has its limits. If physical qubits have a high error rate, adding more qubits can make the situation worse rather than better. But if the error rate of physical qubits falls below a certain threshold, the balance shifts. Adding more qubits can significantly improve the error rate of the logical qubits.

A Breakthrough in Error Correction

In a paper published in Nature last December, Michael Newman and his team at Google Quantum AI have achieved a major breakthrough in quantum error correction. They demonstrated that by adding physical qubits to a system, the error rate of a logical qubit drops sharply. This finding shows that they’ve crossed the critical threshold where error correction becomes effective. The research marks a significant step forward, moving quantum computers closer to practical, large-scale applications.

The concept of error correction itself isn’t new — it is already used in classical computers. On traditional systems, information is stored as bits, which can be prone to errors. To prevent this, error-correcting codes replicate each bit, ensuring that errors can be corrected by a majority vote. However, in quantum systems, things are more complicated. Unlike classical bits, qubits can suffer from various types of errors, including decoherence and noise, and quantum computing operations themselves can introduce additional errors.

Moreover, unlike classical bits, measuring a qubit’s state directly disturbs it, making it much harder to identify and correct errors without compromising the computation. This makes quantum error correction particularly challenging.

The Quantum Threshold

Quantum error correction relies on the principle of redundancy. To protect quantum information, multiple physical qubits are used to form a logical qubit. However, this redundancy is only beneficial if the error rate is low enough. If the error rate of physical qubits is too high, adding more qubits can make the error correction process counterproductive.

Google’s recent achievement demonstrates that once the error rate of physical qubits drops below a specific threshold, adding more qubits improves the system’s resilience. This breakthrough brings researchers closer to achieving large-scale quantum computing systems capable of solving complex problems that classical computers cannot.

Moving Forward

While significant progress has been made, quantum computing still faces many engineering challenges. Quantum systems require extremely controlled environments, such as ultra-low temperatures, and the smallest disturbances can lead to errors. Despite these hurdles, Google’s breakthrough in quantum error correction is a major step toward realizing the full potential of quantum computing.

By improving error correction and ensuring that more reliable logical qubits are created, researchers are steadily paving the way for practical quantum computers. This achievement moves quantum computing closer to becoming a transformative tool for science and technology.

Space & Physics

MIT Pioneers Real-Time Observation of Unconventional Superconductivity in Magic-Angle Graphene

Physicists have directly observed unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle twisted tri-layer graphene using a new experimental platform, revealing a unique pairing mechanism

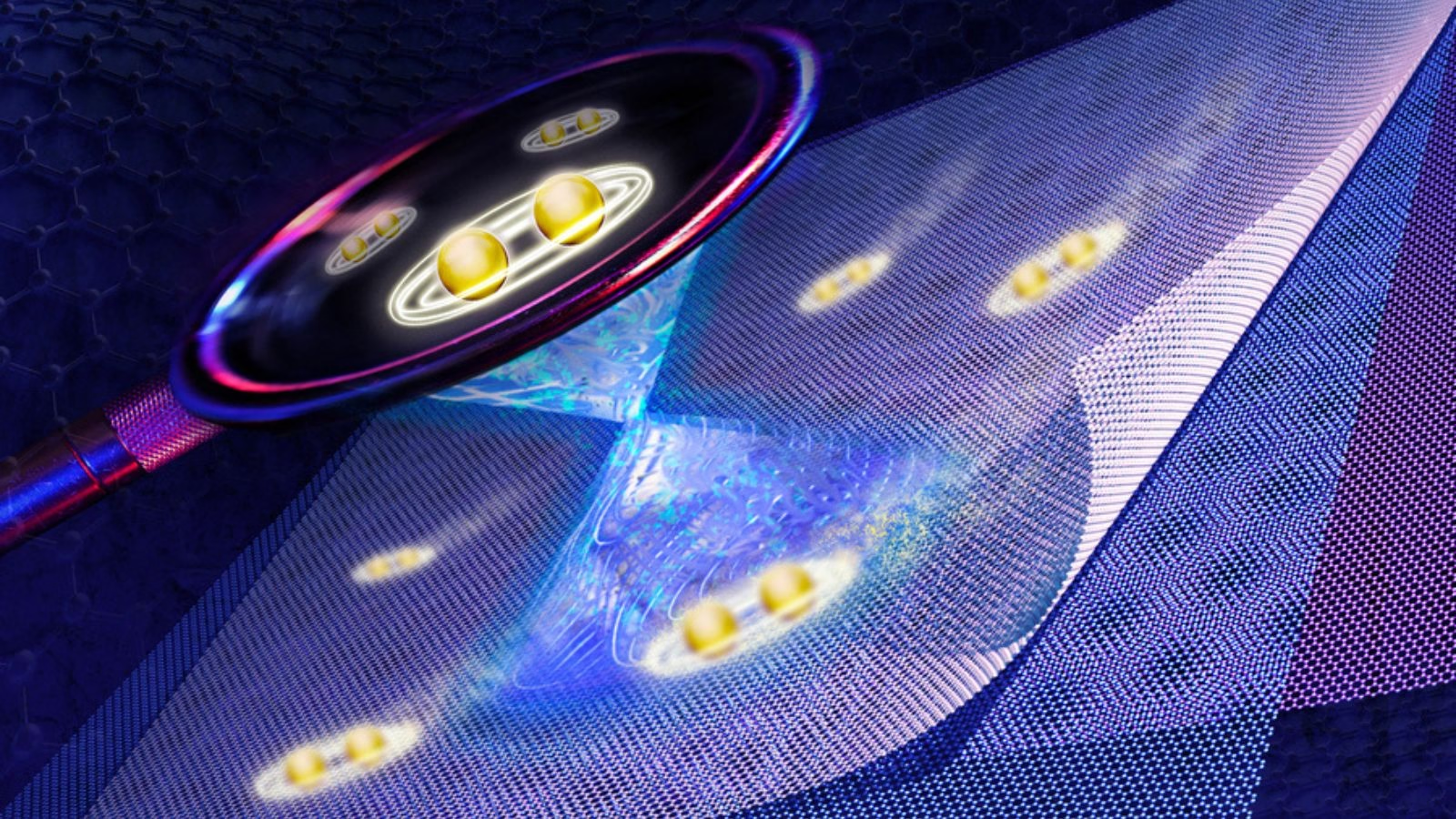

MIT physicists have unveiled compelling direct evidence for unconventional superconductivity in “magic-angle” twisted tri-layer graphene—an atomically engineered material that could reimagine the future of energy transport and quantum technologies. Their new experiment marks a pivotal step forward, offering a fresh perspective on how electrons synchronize in precisely stacked two-dimensional materials, potentially laying the groundwork for next-generation superconductors that function well above current temperature limits.

Instead of looking merely at theoretical possibilities, the MIT team built a novel platform that lets researchers visualize the superconducting gap “as it emerges in real-time within 2D materials,” said co-lead author Shuwen Sun in a media statement. This gap is crucial, reflecting how robust the material’s superconducting state is during temperature changes—a key indicator for practical applications.

What’s striking, said Jeong Min Park, study co-lead author, is that the superconducting gap in magic-angle graphene differs starkly from the smooth, uniform profile seen in conventional superconductors. “We observed a V-shaped gap that reveals an entirely new pairing mechanism—possibly driven by the electrons themselves, rather than crystal vibrations,” Park said. Such direct measurement is a “first” for the field, giving scientists a more refined tool for identifying and understanding unconventional superconductivity.

Senior author Pablo Jarillo-Herrero emphasized that their method could help crack the code behind room-temperature superconductors: “This breakthrough may trigger deeper insights not just for graphene, but for the entire class of twistronic materials. Imagine grids and quantum computers that operate with zero energy loss—this is the holy grail we’re moving toward,” Jarillo-Herrero said in the MIT release.

Collaborators included scientists from Japan’s National Institute for Materials Science, broadening the impact of the research. The discovery builds on years of progress since the first magic-angle graphene experiments in 2018, opening what many now call the “twistronics” era—a field driven by stacking and twisting atom-thin materials to unlock uniquely quantum properties.

Looking ahead, the team plans to expand its analysis to other ultra-thin structures, hoping to map out electronic behavior not only for superconductors, but for a wider range of correlated quantum phases. “We can now directly observe electron pairs compete and coexist with other quantum states—this could allow us to design new materials from the ground up,” said Park in her public statement.

The research underscores the value of visualization in fundamental physics, suggesting that direct observation may be the missing link to controlling quantum phenomena for efficient, room-temperature technology.

Space & Physics

Atoms Speak Out: Physicists Use Electrons as Messengers to Unlock Secrets of the Nucleus

Physicists at MIT have devised a table-top method to peer inside an atom’s nucleus using the atom’s own electrons

Physicists at MIT have developed a pioneering method to look inside an atom’s nucleus — using the atom’s own electrons as tiny messengers within molecules rather than massive particle accelerators.

In a study published in science, the researchers demonstrated this approach using molecules of radium monofluoride, which pair a radioactive radium atom with a fluoride atom. The molecules act like miniature laboratories where electrons naturally experience extremely strong electric fields. Under these conditions, some electrons briefly penetrate the radium nucleus, interacting directly with protons and neutrons inside. This rare intrusion leaves behind a measurable energy shift, allowing scientists to infer details about the nucleus’ internal structure.

The team observed that these energy shifts, though minute — about one millionth of the energy of a laser photon — provide unambiguous evidence of interactions occurring inside the nucleus rather than outside it. “We now have proof that we can sample inside the nucleus,” said Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz, the Thomas A. Franck Associate Professor of Physics at MIT, in a statement. “It’s like being able to measure a battery’s electric field. People can measure its field outside, but to measure inside the battery is far more challenging. And that’s what we can do now.”

Traditionally, exploring nuclear interiors required kilometer-long particle accelerators to smash high-speed beams of electrons into targets. The MIT technique, by contrast, achieves similar insight with a table-top molecular setup. It makes use of the molecule’s natural electric environment to magnify these subtle interactions.

The radium nucleus, unlike most which are spherical, has an asymmetric “pear” shape that makes it a powerful system for studying violations of fundamental physical symmetries — phenomena that could help explain why the universe contains far more matter than antimatter. “The radium nucleus is predicted to be an amplifier of this symmetry breaking, because its nucleus is asymmetric in charge and mass, which is quite unusual,” Garcia Ruiz explained.

To conduct their experiments, the researchers produced radium monofluoride molecules at CERN’s Collinear Resonance Ionization Spectroscopy (CRIS) facility, trapped and cooled them in laser-guided chambers, and then measured laser-induced energy transitions with extreme precision. The work involved MIT physicists Shane Wilkins, Silviu-Marian Udrescu, and Alex Brinson, alongside international collaborators.

“Radium is naturally radioactive, with a short lifetime, and we can currently only produce radium monofluoride molecules in tiny quantities,” said Wilkins. “We therefore need incredibly sensitive techniques to be able to measure them.”

As Udrescu added, “When you put this radioactive atom inside of a molecule, the internal electric field that its electrons experience is orders of magnitude larger compared to the fields we can produce and apply in a lab. In a way, the molecule acts like a giant particle collider and gives us a better chance to probe the radium’s nucleus.”

Going forward, the MIT team aims to cool and align these molecules so that the orientation of their pear-shaped nuclei can be controlled for even more detailed mapping. “Radium-containing molecules are predicted to be exceptionally sensitive systems in which to search for violations of the fundamental symmetries of nature,” Garcia Ruiz said. “We now have a way to carry out that search”

Space & Physics

Physicists Double Precision of Optical Atomic Clocks with New Laser Technique

MIT researchers develop a quantum-enhanced method that doubles the precision and stability of optical atomic clocks, paving the way for portable, ultra-accurate timekeeping.

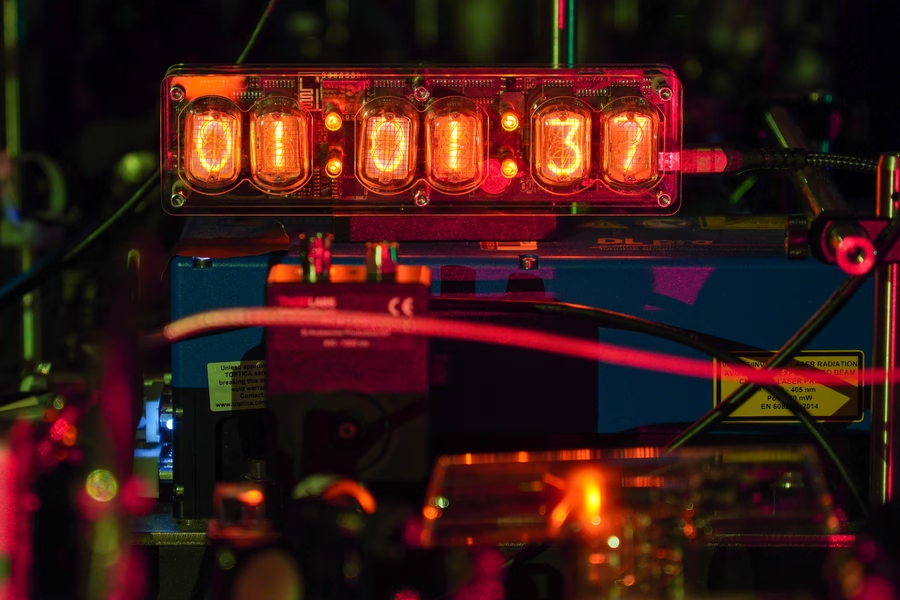

MIT physicists have unveiled a new technique that could significantly improve the precision and stability of next-generation optical atomic clocks, devices that underpin everything from mobile transactions to navigation apps. In a recent media statement, the MIT team explained: “Every time you check the time on your phone, make an online transaction, or use a navigation app, you are depending on the precision of atomic clocks. An atomic clock keeps time by relying on the ‘ticks’ of atoms as they naturally oscillate at rock-steady frequencies.”

Current atomic clocks rely on cesium atoms tracked with lasers at microwave frequencies, but scientists are advancing to clocks based on faster-ticking atoms like ytterbium, which can be tracked with lasers at higher, optical frequencies and discern intervals up to 100 trillion times per second.

A research group at MIT, led by Vladan Vuletić, the Lester Wolfe Professor of Physics, detailed that their newly developed method harnesses a laser-induced “global phase” in ytterbium atoms and boosts this effect using quantum amplification. Vuletić stated, “We think our method can help make these clocks transportable and deployable to where they’re needed.” The approach, called global phase spectroscopy, doubles the precision of an optical atomic clock, enabling it to resolve twice as many ticks per second compared to standard setups, and promises further gains with increasing atom counts.

The technique could pave the way for portable optical atomic clocks able to measure all manner of phenomena in various locations. Vuletić summarized the broader scientific ambitions: “With these clocks, people are trying to detect dark matter and dark energy, and test whether there really are just four fundamental forces, and even to see if these clocks can predict earthquakes.”

The MIT team has previously demonstrated improved clock precision by quantumly entangling hundreds of ytterbium atoms and using time reversal tricks to amplify their signals. Their latest advance applies these methods to much faster optical frequencies, where stabilizing the clock laser has always been a major challenge. “When you have atoms that tick 100 trillion times per second, that’s 10,000 times faster than the frequency of microwaves,” said Vuletić in the statement. Their experiments revealed a surprisingly useful “global phase” information about the laser frequency, previously thought irrelevant, unlocking the potential for even greater accuracy.

The research, led by Vuletić and joined by Leon Zaporski, Qi Liu, Gustavo Velez, Matthew Radzihovsky, Zeyang Li, Simone Colombo, and Edwin Pedrozo-Peñafiel of the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, was published in Nature. They believe the technical benefits of the new method will make atomic clocks easier to run and enable stable, transportable clocks fit for future scientific exploration, including earthquake prediction, fundamental physics, and global time standards.

-

Space & Physics6 months ago

Space & Physics6 months agoIs Time Travel Possible? Exploring the Science Behind the Concept

-

Know The Scientist6 months ago

Know The Scientist6 months agoNarlikar – the rare Indian scientist who penned short stories

-

Know The Scientist5 months ago

Know The Scientist5 months agoRemembering S.N. Bose, the underrated maestro in quantum physics

-

Space & Physics3 months ago

Space & Physics3 months agoJoint NASA-ISRO radar satellite is the most powerful built to date

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoAxiom-4 will see an Indian astronaut depart for outer space after 41 years

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoShukla is now India’s first astronaut in decades to visit outer space

-

Society5 months ago

Society5 months agoWhy the Arts Matter As Much As Science or Math

-

Earth5 months ago

Earth5 months agoWorld Environment Day 2025: “Beating plastic pollution”